Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait Islands.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 759,705 (2016)[1] 3.1% of Australia's population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Northern Territory | 30.3% |

| Tasmania | 5.5% |

| Queensland | 4.6% |

| Western Australia | 3.9% |

| New South Wales | 3.4% |

| South Australia | 2.5% |

| Australian Capital Territory | 1.9% |

| Victoria | 0.9% |

| Languages | |

| Several hundred Australian Aboriginal languages, many no longer spoken, Australian English, Australian Aboriginal English, Kriol | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Christian (mainly Anglican and Catholic),[2] large minority no religious affiliation,[2] small numbers of other religions, various local indigenous religions grounded in Australian Aboriginal mythology | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Torres Strait Islanders, Aboriginal Tasmanians, Papuans | |

Aboriginal Australians comprise many distinct peoples who have developed across Australia for over 50,000 years. These peoples have a broadly shared, though complex, genetic history, but it is only in the last two hundred years that they have been defined and started to self-identify as a single group. The definition of the term "Aboriginal" has changed over time and place, with the importance of family lineage, self-identification and community acceptance all being of varying importance.

The term Indigenous Australians refers to Aboriginal Australians as well as Torres Strait Islanders, and the term should only be used when both groups are included in the topic being addressed, or by self-identification by a person as Indigenous. (Torres Strait Islanders are ethnically and culturally distinct, despite extensive cultural exchange with some of the Aboriginal groups, and the Torres Strait Islands are mostly part of Queensland but have a separate governmental status.)

In the past, Aboriginal Australians lived over large sections of the continental shelf and were isolated on many of the smaller offshore islands and Tasmania when the land was inundated at the start of the Holocene inter-glacial period, about 11,700 years ago. Studies regarding the genetic makeup of Aboriginal groups are still ongoing, but evidence has suggested that they have genetic inheritance from ancient Asian but not more modern peoples, share some similarities with Papuans, but have been isolated from Southeast Asia for a very long time. Before extensive European settlement, there were over 250 Aboriginal languages.

In the 2016 Australian Census, Indigenous Australians comprised 3.3% of Australia's population, with 91% of these identifying as Aboriginal only, 5% Torres Strait Islander, and 4% both. They also live throughout the world as part of the Australian diaspora.

Most Aboriginal people speak English, with Aboriginal phrases and words being added to create Australian Aboriginal English (which also has a tangible influence of Aboriginal languages in the phonology and grammatical structure).

Aboriginal Australians, along with Torres Strait Islander people, have a number of health and economic deprivations in comparison with the wider Australian community.

Origins

.jpg)

The ancestors of present-day Aboriginal Australians migrated from Asia by sea during the Pleistocene era and lived over large sections of the Australian continental shelf when the sea levels were lower and Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea were part of the same landmass. As sea levels rose, the people on the Australian mainland and nearby islands became increasingly isolated, and some were isolated on Tasmania and some of the smaller offshore islands when the land was inundated at the start of the Holocene, the inter-glacial period which started about 11,700 years ago and persists today.[3]

Studies regarding the genetic makeup of Aboriginal groups are still ongoing, but evidence has suggested that they have genetic inheritance from ancient Asian but not more modern peoples, share some similarities with Papuans, but have been isolated from Southeast Asia for a very long time. Before extensive European settlement, there were over 250 Aboriginal languages.[4][5]

Scholars have disagreed whether the closest kin of Aboriginal Australians outside Australia were certain South Asian groups or African groups. The latter would imply a migration pattern in which their ancestors passed through South Asia to Australia without intermingling genetically with other populations along the way.[6]

In a 2011 genetic study by Ramussen et al., researchers took a DNA sample from an early 20th century lock of an Aboriginal person's hair. They found that the ancestors of the Aboriginal population split off from the Eurasian population between 62,000 and 75,000 BP, whereas the European and Asian populations split only 25,000 to 38,000 years BP, indicating an extended period of Aboriginal genetic isolation. These Aboriginal ancestors migrated into South Asia and then into Australia, where they stayed, with the result that, outside of Africa, the Aboriginal peoples have occupied the same territory continuously longer than any other human populations. These findings suggest that modern Aboriginal peoples are the direct descendants of migrants who left Africa up to 75,000 years ago.[7][8] This finding is compatible with earlier archaeological finds of human remains near Lake Mungo that date to approximately 40,000 years ago.

The same genetic study of 2011 found evidence that Aboriginal peoples carry some of the genes associated with the Denisovan (a species of human related to but distinct from Neanderthals) peoples of Asia; the study suggests that there is an increase in allele sharing between the Denisovans and the Aboriginal Australians genome compared to other Eurasians and Africans. Examining DNA from a finger bone excavated in Siberia, researchers concluded that the Denisovans migrated from Siberia to tropical parts of Asia and that they interbred with modern humans in South-East Asia 44,000 years BP, before Australia separated from New Guinea approximately 11,700 years BP. They contributed DNA to Aboriginal Australians along with present-day New Guineans and an indigenous tribe in the Philippines known as Mamanwa. This study makes Aboriginal Australians one of the oldest living populations in the world and possibly the oldest outside of Africa, confirming they may also have the oldest continuous culture on the planet.[9] The idea of the "oldest continuous culture" is based on the geographical isolation of the Aboriginal peoples, with little or no interaction with outside cultures before some contact with Makassan fisherman and Dutch explorers up to 500 years BP.[10]

A 2016 study by the University of Cambridge reported that Papuan and Aboriginal peoples developed distinct markers around 58,000 years BP that distinguished them from the original out-of-Africa migration around 72,000 years BP, pointing to a single migration henceforth untouched by other groups. The study suggests that it was about 50,000 years ago that these peoples reached Sahul (the supercontinent consisting of present-day Australia and its islands and New Guinea). The sea levels rose and isolated Australia (and Tasmania) about 10,000 years ago, but Aboriginal Australians and Papuans diverged from each other genetically earlier, about 37,000 years BP, possibly because the remaining land bridge was impassable, and it was this isolation which makes it the world’s oldest civilisation. The study also found evidence of an unknown hominin group, distantly related to Denisovans, with whom the Aboriginal and Papuan ancestors must have interbred, leaving a trace of about 4% in most Aboriginal Australians' genome. There is, however, huge genetic diversity among Aboriginal Australians based on geographical distribution.[11]

The Papuans have more shared alleles than Aboriginal peoples. The data suggest that modern and archaic humans interbred in Asia before the migration to Australia.[12]

One 2017 paper in Nature evaluated artifacts in Kakadu and concluded "Human occupation began around 65,000 years ago".[13]

A 2013 study by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology found that there was a migration of genes from India to Australia around 2000 BCE. The researchers had two theories for this: either some Indians had contact with people in Indonesia who eventually transferred those genes from India to Aboriginal Australians, or that a group of Indians migrated all the way from India to Australia and intermingled with the locals directly.[14][15]

In a 2001 study, blood samples were collected from some Warlpiri members of the Northern Territory to study the genetic makeup of the Warlpiri Tribe of Aboriginal Australians, who are not representative of all Aboriginal Tribes in Australia. The study concluded that the Warlpiri are descended from ancient Asians whose DNA is still somewhat present in Southeastern Asian groups, although greatly diminished. The Warlpiri DNA also lacks certain information found in modern Asian genomes, and carries information not found in other genomes, reinforcing the idea of ancient Aboriginal isolation.[16]

Aboriginal Australians are genetically most similar to the indigenous populations of Papua New Guinea, and more distantly related to groups from East Indonesia. They are quite distinct from the indigenous populations of Borneo and Malaysia, sharing relatively little genomic information as compared to the groups from Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. This indicates that Australia was isolated for a long time from the rest of Southeast Asia, and remained untouched by migrations and population expansions into that area.[16]

Genetic adaptations

Aboriginal Australians possess inherited abilities to stand a wide range of environmental temperatures in various ways. A 1958 study comparing cold adaptation in the desert-dwelling Pitjantjatjara people compared with a group of white people showed that the cooling adaptation of the Aboriginal group differed from that of the white people, and that they were able to sleep more soundly through a cold desert night.[17] A 2014 Cambridge University study found that a beneficial mutation in two genes which regulate thyroxine, a hormone involved in regulating body metabolism, helps to regulate body temperature in response to fever. The effect of this is that the desert people are able to have a higher body temperature without accelerating the activity of the whole of the body, which can be especially detrimental in childhood diseases. This helps protect people to survive the side-effects of infection.[18][19]

Location and demographics

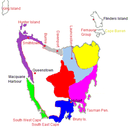

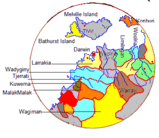

Aboriginal Australians have lived for tens of thousands of years on the continent of Australia, through its various changes in landmass. The area within Australia's borders today includes the islands of Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island,[20] the Tiwi Islands and Groote Eylandt. Indigenous people of the Torres Strait Islands, however, are not Aboriginal.[21][22][23][24]

In the 2016 Australian Census, Indigenous Australians comprised 3.3% of Australia's population, with 91% of these identifying as Aboriginal only, 5% Torres Strait Islander, and 4% both.[25]

Aboriginal Australians also live throughout the world as part of the Australian diaspora.

Languages

Most Aboriginal people speak English, with Aboriginal phrases and words being added to create Australian Aboriginal English (which also has a tangible influence of Aboriginal languages in the phonology and grammatical structure). Some Aboriginal people, especially those living in remote areas, are multi-lingual. Many of the original 250–400 Aboriginal languages are endangered or extinct, although some efforts are being made at language revival for some.

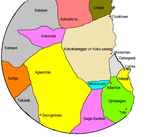

Aboriginal Australian peoples

Dispersing across the Australian continent over time, the ancient people expanded and differentiated into distinct groups, each with its own language and culture.[26] More than 400 distinct Australian Aboriginal peoples have been identified, distinguished by names designating their ancestral languages, dialects, or distinctive speech patterns.[27] According to noted anthropologist, archaeologist and sociologist Harry Lourandos, historically, these groups lived in three main cultural areas, the Northern, Southern, and Central cultural areas. The Northern and Southern areas, having richer natural marine and woodland resources, were more densely populated than the Central area.[26]

Geographically-based names

There are various other names from Australian Aboriginal languages commonly used to identify groups based on geography, known as demonyms, including:

- Anangu in northern South Australia, and neighbouring parts of Western Australia and Northern Territory

- Goorie (variant pronunciation and spelling of Koori) in South East Queensland and some parts of northern New South Wales

- Koori (or Koorie) in New South Wales and Victoria (Aboriginal Victorians)

- Murri in southern Queensland

- Nunga in southern South Australia

- Noongar in southern Western Australia

- Palawah (or Pallawah) in Tasmania

- Tiwi on Tiwi Islands off Arnhem Land (NT)

A few examples of sub-groups

Other group names are based on the language group or specific dialect spoken. These also coincide with geographical regions of varying sizes. A few examples are:

- Anindilyakwa on Groote Eylandt (off Arnhem Land), NT

- Arrernte in central Australia

- Bininj in Western Arnhem Land (NT)[28]

- Gunggari in south-west Queensland[29]

- Muruwari people in New South Wales

- Luritja (Kukatja), an Anangu sub-group based on language

- Ngunnawal in the Australian Capital Territory and surrounding areas of New South Wales

- Pitjantjatjara, an Anangu sub-group based on language

- Wangai in the Western Australian Goldfields

- Warlpiri (Yapa) in western central Northern Territory

- Yamatji in central Western Australia

- Yolngu in eastern Arnhem Land (NT)

Difficulties defining groups

However these lists are neither exhaustive nor definitive, and there are overlaps. Different approaches have been taken by non-Aboriginal scholars in trying to understand and define Aboriginal culture and societies, some focussing on the micro level (tribe, clan, etc.) and others on shared languages and cultural practices spread over large regions defined by ecological factors. Anthropologists have encountered many difficulties in trying to define what constitutes an Aboriginal people/community/group/tribe, let alone naming them. Knowledge of pre-colonial Aboriginal cultures and societal groupings is still largely dependent on the observers' interpretations, which were filtered through colonial ways of viewing societies.[30]

Aboriginal identity

The term Aboriginal Australians includes many distinct peoples who have developed across Australia for over 50,000 years.[13][31] These peoples have a broadly shared, though complex, genetic history,[6][15] but it is only in the last two hundred years that they have been defined and started to self-identify as a single group.[32][33]

The definition of the term "Aboriginal" has changed over time and place, with the importance of family lineage, self-identification and community acceptance all being of varying importance.[34][35][36]

The term Indigenous Australians refers to Aboriginal Australians as well as Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the term should only be used when both groups are included in the topic being addressed, or by self-identification by a person as Indigenous. (Torres Strait Islanders are ethnically and culturally distinct,[37] despite extensive cultural exchange with some of the Aboriginal groups,[38] and the Torres Strait Islands are mostly part of Queensland but have a separate governmental status.)

Health and disadvantage

Aboriginal Australians, along with Torres Strait Islander people, have a number of health and economic deprivations in comparison with the wider Australian community.[39][40]

Viability of remote communities

Indigenous "communities" in remote Australia are typically small, isolated towns with basic facilities, on traditionally owned land. These communities have between 20 and 300 inhabitants and are often closed to outsiders for cultural reasons. The long-term viability and resilience of Aboriginal communities in desert areas has been discussed by scholars and policy-makers. A 2007 report by the CSIRO stressed the importance of taking a demand-driven approach to services in desert settlements, and concluded that "if top-down solutions continue to be imposed without appreciating the fundamental drivers of settlement in desert regions, then those solutions will continue to be partial, and ineffective in the long term".[41]

See also

- Aboriginal Centre for the Performing Arts (ACPA)

- Aboriginal cultures of Western Australia

- Aboriginal South Australians

- Aboriginal Tasmanians

- Aboriginal Victorians

- Australian Aboriginal religion and mythology

- Australian Aboriginal culture

- Australian Aboriginal kinship

- Aboriginal land rights in Australia

- Indigenous Australian art

- Indigenous Australian music

- First Nations Media Australia

- List of Aboriginal missions in New South Wales

- List of Indigenous Australian firsts

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award

- Native title in Australia

- Stolen Generations

- Supply Nation

References

- "Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians". Australian Bureau of Statistics. June 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- "4713.0 – Population Characteristics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4 May 2010.

- Rebe Taylor (2002). Unearthed: The Aboriginal Tasmanians of Kangaroo Island. Kent Town: Wakefield Press. ISBN 978-1-86254-552-6.

- "Languages of Aboriginal And Torres Strait Islander Peoples – a Uniquely Australian Heritage". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- "Community, identity, wellbeing: The report of the Second National Indigenous Languages Survey". AIATSIS. 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Edwards, W.H. (2004). An introduction to Aboriginal societies (2nd ed.). Social Science Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-876633-89-9.

- Rasmussen, Morten; Guo, Xiaosen; et al. (7 October 2011). "An Aboriginal Australia Genome Reveals Separate Human Dispersals into Asia". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 334 (6052): 94–98. Bibcode:2011Sci...334...94R. doi:10.1126/science.1211177. PMC 3991479. PMID 21940856.

- "The first Aboriginal genome sequence confirms Australia's native people left Africa 75,000 years ago". Australian Geographic. 23 September 2011.

- "DNA confirms Aboriginal culture is one of the Earth's oldest". Australian Geographic. 23 September 2011.

- Pearson, Luke (21 December 2016). "What is a 'continuous culture'... and are Aboriginal cultures the oldest?". NITV. Special Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Klein, Christopher (23 September 2016). "DNA Study Finds Aboriginal Australians World's Oldest Civilization". History. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

Updated Aug 22, 2018

- Callaway, Ewen (2011). "First Aboriginal genome sequenced". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.551. ISSN 1476-4687. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; Marwick, Ben; Fullagar, Richard; Wallis, Lynley; Smith, Mike; Roberts, Richard G.; Hayes, Elspeth; Lowe, Kelsey; Carah, Xavier; Florin, S. Anna; McNeil, Jessica; Cox, Delyth; Arnold, Lee J.; Hua, Quan; Huntley, Jillian; Brand, Helen E. A.; Manne, Tiina; Fairbairn, Andrew; Shulmeister, James; Lyle, Lindsey; Salinas, Makiah; Page, Mara; Connell, Kate; Park, Gayoung; Norman, Kasih; Murphy, Tessa; Pardoe, Colin (2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago". Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28726833.

- Sanyal, Sanjeev (2016). The ocean of churn : how the Indian Ocean shaped human history. Gurgaon, Haryana, India. p. 59. ISBN 9789386057617. OCLC 990782127.

- MacDonald, Anna (15 January 2013). "Research shows ancient Indian migration to Australia". ABC News.

- Huoponen, Kirsi; Schurr, Theodore G.; et al. (1 September 2001). "Mitochondrial DNA variation in an Aboriginal Australian population: evidence for genetic isolation and regional differentiation". Human Immunology. 62 (9): 954–969. doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(01)00294-4. PMID 11543898.

- Scholander, P. F.; Hammel, H. T.; et al. (1 September 1958). "Cold Adaptation in Australian Aborigines". Journal of Applied Physiology. 13 (2): 211–218. doi:10.1152/jappl.1958.13.2.211. PMID 13575330.

- Caitlyn Gribbin (29 January 2014). "Genetic mutation helps Aboriginal people survive tough climate, research finds" (text and audio). ABC News.

- Qi, Xiaoqiang; Chan, Wee Lee; Read, Randy J.; Zhou, Aiwu; Carrell, Robin W. (22 March 2014). "Temperature-responsive release of thyroxine and its environmental adaptation in Australians". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 281 (1779): 20132747. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2747. PMC 3924073. PMID 24478298.

- "Preferences in terminology when referring to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples" (PDF). Gulanga Good Practice Guides. ACT Council of Social Service Inc. December 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976". Federal Register of Legislation. No. 191, 1976: Compilation No. 41. Australian Government. 4 April 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

s 3: Aboriginal means a person who is a member of the Aboriginal race of Australia....12AAA. Additional grant to Tiwi Land Trust...

- "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Act 2005". Federal Register of Legislation. No. 150, 1989: Compilation No. 54. Australian Government. 4 April 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019. s 4: "Aboriginal person means a person of the Aboriginal race of Australia."

- Venbrux, Eric (1995). A death in the Tiwi islands: conflict, ritual, and social life in an Australian aboriginal community. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47351-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rademaker, Laura (7 February 2018). "Tiwi Christianity: Aboriginal histories, Catholic mission and a surprising conversion". ABC Religion and Ethics. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians". Australian Bureau of Statistics. June 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Lourandos, Harry. New Perspectives in Australian Prehistory, Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom (1997) ISBN 0-521-35946-5

- Horton, David (1994) The Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander History, Society, and Culture, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra. ISBN 0-85575-234-3.

- Garde, Murray. "bininj". Bininj Kunwok Dictionary. Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- "General Reference". Life and Times of the Gunggari People, QLD (Pathfinder). Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- Monaghan, Paul (2017). "Chapter 1: Structures of Aboriginal life at the time of colonisation". In Brock, Peggy; Gara, Tom (eds.). Colonialism and its Aftermath: A history of Aboriginal South Australia. Wakefield Press. pp. 10, 12. ISBN 9781743054994.

- Walsh, Michael; Yallop, Colin (1993). Language and Culture in Aboriginal Australia. Aboriginal Studies Press. pp. 191–193. ISBN 9780855752415.

- Fesl, Eve D. "'Aborigine' and 'Aboriginal'". (1986) 1(20) Aboriginal Law Bulletin 10 Accessed 19 August 2011

- "Don't call me indigenous: Lowitja". The Age. Melbourne. Australian Associated Press. 1 May 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- "Aboriginality and Identity: Perspectives, Practices and Policies" (PDF). New South Wales AECG Inc. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- Blandy, Sarah; Sibley, David (2010). "Law, boundaries and the production of space". Social & Legal Studies. 19 (3): 275–284. doi:10.1177/0964663910372178. "Aboriginal Australians are a legally defined group" (p 280).

- Malbon, Justin (2003). "The Extinguishment of Native Title—The Australian Aborigines as Slaves and Citizens". Griffith Law Review. 12 (2): 310–335. doi:10.1080/10383441.2003.10854523. Aboriginal Australians have been "assigned a separate legally defined status" (p 322).

- "About the Torres Strait". Torres Strait Shire Council. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Australia Now – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples". 8 October 2006. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "4704.0 - The Health and Welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Oct 2010". Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Government. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "Indigenous Socioeconomics Indicators, Benefits and Expenditure". Parliament of Australia. 7 August 2001. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Smith, M. S.; Moran, M.; Seemann, K. (2008). "The 'viability' and resilience of communities and settlements in desert Australia". The Rangeland Journal. 30: 123. doi:10.1071/RJ07048.

Further reading

- "Start exploring Australian Aboriginal culture". Creative Spirits. 24 December 2018.

- "Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies". AIATSIS.

External links

| Library resources about Aboriginal Australians |

.jpg)