William Rainey

William Rainey RI RBA ROI (21 July 1852 – 24 January 1936) was a British Artist and Illustrator. He was a prolific illustrator of both books and magazines and illustrated about 200 books during his career. He also kept painting and exhibited his work frequently. Rainey also wrote and illustrated six books himself, one was a colourful book for young children, the other five were juvenile fiction.

William Rainey | |

|---|---|

| Born | 21 July 1852 Kennington, London, England |

| Died | 24 January 1936 (aged 83) Eastbourne, Sussex, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Artist and illustrator |

| Years active | 1872–1936 |

| Known for | Illustrations for boys adventure books |

Early life

Rainey was born in Kennington, London, on 21 July 1852. He was the third of eight children[note 1] of the distinguished anatomist and teacher George Rainey (1801 – 16 November 1884)[1] and Martha Dee, a farmer's daughter (c. 1827 – 27 May 1905). Rainey's parents were married at the parish church in Twyning, Gloucestershire, England on 31 December 1846.[2] Rainey was originally intended for a career at sea, but his father, who had himself run away from an early apprenticeship,[3] allowed him instead to study at the South Kensington School of Art.[4] The 1871 census shows that, by the time Rainey was 18, he was a student at the Royal Academy.

Exhibitions

He was a regular exhibitor at the Royal Academy, starting in 1878 with Lyme Regis. Between 1878 and 1904 he exhibited 17 times (showing two works in both 1884 and 1901) at the Royal Academy,[5] and continued to exhibit thereafter, including two works at the Franco-British exhibition in 1908.[6] Rainey exhibited at The Royal Academy, Royal Institute of Oil Painters, the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours and the RBA.[7]

Rainey was elected a member if the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours on 6 April 1891,[8] and a member of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters on 25 November 1981.[9] Rainey won medals for watercolours both the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the 1900 Paris Exhibition.[10] Rainey was still exhibiting in the 1930s,[11][12] even though by now he has moved on to the retired list of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours,[11] being an honorary member from 1930.[13]

Marriage and family

Rainey married Harriet Matilda Bennett, (12 February 1860 – c. March 1919), the daughter of Thomas Bennett, a civil engineer, at the Parish Church of St George the Martyr, Holborn,[note 2] London on 11 June 1877. The couple had four children:

- Florence Harriet Bennett (1878 – 1959), who was his executor at his death in 1936

- Edith Elsie Rainey(1882 – 1896), who died as a teenager

- George William Bennett Rainey (Q2 1886 – 1956), Shown as assisting his father in the 1911 census.

- Victor Thomas James Rainey (Q3 1889 – 30 September 1917), a Second Lieutenant in the Devonshire Regiment, killed at Ypres in the First World War.

Works

Rainey exhibited paintings throughout his life, it was a form of marketing which earned him commissions.[14]

Magazine illustration

Rainey did more illustration for magazines that for books. Among the magazines he illustrated for were:

- Atalanta

- Black and White

- The Boy's Own Paper

- Cassell's Family Magazine

- Chums

- The Girl's Own Paper

- Good Words

- The Graphic

- The Harmsworth Magazine

- The Illustrated London News

- Little Folks

- The Ludgate Monthly

- The Penny Magazine

- Punch

- The Quiver

- The Sphere

- Springtime

- The Strand Magazine

- Sunday at Home

- The Temperance Monthly

- Young England

- The Windsor Magazine

Examples of magazine illustration

Rainey illustrated many stories for magazines. The first example was story that was translated into French for Hetzel's Magasin d’Éducation et de Récréation.[note 4] The story was Jock et ses amis (Jock and his Friends) write by A. Decker from an original by E. Hohler.[note 5]

What do you think of that?

What do you think of that? I don't want to go

I don't want to go Jock managed to grab the leaping dog

Jock managed to grab the leaping dog Mr. Grimshaw should have left you with me

Mr. Grimshaw should have left you with me So you are Dick Pole's son?

So you are Dick Pole's son? He had lunch while Tramp stood quietly in a chair

He had lunch while Tramp stood quietly in a chair The two men turn around at his sudden appearance.

The two men turn around at his sudden appearance. Then the child became silent, absorbed in his work

Then the child became silent, absorbed in his work My name is Mollv.

My name is Mollv. I just sat in the stream

I just sat in the stream He managed to tear himself away from this swamp

He managed to tear himself away from this swamp I will tell your master that you are an old rascal

I will tell your master that you are an old rascal I wanted to keep you always close to me.

I wanted to keep you always close to me. She looked at him with a pleading look

She looked at him with a pleading look I am happy with this last farewell

I am happy with this last farewell Jock felt the warmest welcome at the farm

Jock felt the warmest welcome at the farm He fled across the fields and hid

He fled across the fields and hid You are too young, too unreasonable to decide such a case

You are too young, too unreasonable to decide such a case I didn't imagine it was so expensive

I didn't imagine it was so expensive Tramp and Jock shared equally.

Tramp and Jock shared equally. Then he slid to the window, and looked into the interior

Then he slid to the window, and looked into the interior He resumed his run when the farmer reached the garden gate.

He resumed his run when the farmer reached the garden gate. The boy's clothes were covered in mud

The boy's clothes were covered in mud He stumbled a few steps and almost fell

He stumbled a few steps and almost fell Mum, is it you?

Mum, is it you?

Rainey also illustrated stories for adults. He was asked to illustrate the first story published in the new Strand Magazine. This was a short story, A Deadly Dilemma, about the dilemma a young man faces between derailing a train or leaving his sweetheart to be run-over, by Grant Allen.

The two lovers walk out

The two lovers walk out The lovers quarrel and part

The lovers quarrel and part She bursts into tears

She bursts into tears Frightened by a young colt, she runs and falls on the railway line

Frightened by a young colt, she runs and falls on the railway line Seeing his love fallen on the track and a train approaching, he grabs a pole to derail the train

Seeing his love fallen on the track and a train approaching, he grabs a pole to derail the train The train driver pulls the brake lever, but too late

The train driver pulls the brake lever, but too late The engine derails even as he removed the pole, but no-one was hurt

The engine derails even as he removed the pole, but no-one was hurt He carries off his lady love

He carries off his lady love

Book illustration

Rainey was a prolific book illustrator. Kirkpatrick list approximately 200 book titles illustrated by Rainey in his list on the Bear Alley blog,[15] and update the list with a few additional titles for his book.[16] The following list of author's whose work was illustrated by Rainey is based on Kirkpatrick.

- William Adams (1814 – 1848), an Anglican cleric who wrote Christian allegories.

- Helen Atteridge (1856 – 1931), author of children's fiction.[17]

- Harold Avery (1867 – 1943), who wrote school stories for both boys and girls.

- May Baldwin (1862 – 1950), a British author of girl's school stories.[18]

- F. S. Brereton (1872 – 1957), who wrote tales of Imperial heroism for children.

- Maggie Browne (1864 – 1937), Margaret Andrewes née Hamer, an English an author of both non-fiction and fiction for children.

- Ella Lyman Cabot (1866 – 1934), an American educator, lecturer, and author.

- Edith Carrington (1853 – 1929), an English animal rights activist who began to write books on animals from 1889.

- Harriet L. Childe-Pemberton (1852 – 1922), an English poet, short story writer, critic, playwright, and author of juvenile fiction.

- Harry Collingwood (1843 – 1922), a writer of boys' adventure fiction, usually in a nautical setting.

- Samuel Rutherford Crockett (1859 – 1914), a prolific Scottish novelist, who wrote more than 60 books.

- Daniel Defoe (c. 1659 – 1731), who wrote Robinson Crusoe and A Journal of the Plague Year among other works.

- Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870), for whom Jellicoe illustrated posthumous reissues.

- Sarah Doudney (1841 – 1926), an English poet, short story writer, best known for writing hymns and juvenile fiction.

- Henry Drummond (1851 – 1897), a Scottish evangelist, biologist, lecturer, and writer.

- George Manville Fenn (1831 – 1909), a prolific author of fiction for young adults.

- Amy Le Feuvre (1861 – 1929), a prolific author of books for children with a Christian message.[19]

- John Finnemore (1863 – 1915), who wrote books and stories for younger readers, as well as school textbooks.

- Ernest Glanville (1855 – 1925), a South African author, who wrote seventeen historical novels, but is best known for his many short stories.

- Evelyn Everett Green (1856 – 1932), a prolific English novelist who wrote about 350 book, beginning first with pious stories, then historical fiction for girls, and eventually moved to adult romantic fiction.

- G. A. Henty (1832 – 1902), a prolific writer of boy's adventure fiction, often set in a historical context, who had himself served in the military and been a war correspondent.

- Emily Sarah Holt (1836 – 1893), who wrote mainly on historical themes, often with a strong Protestant religious element.

- T. T. Jeans (1871 – 1938), a Royal Navy medical officer who wrote juvenile fiction to show boys what life in the modern navy was really like.

- E. C. Kenyon (1854 – 1925), Edith Caroline Kenton, published more than 50 novels, mainly juvenile fiction, and mostly with the Religious Tract Society as well as translations, biographies, and tracts.[20]

- Skelton Kuppord (1857 – 1934), Sir John Adams a Scottish educationalist.

- Mary Cornwall Legh (1857 – 1941), a British Anglican missionary.

- Robert Leighton (1858 – 1934), a Scottish journalist, editor, and a prolific author of juvenile fiction and non-ficiton books about dogs and their care.

- Emma Leslie (1838 – 1909), Emma Boultwood, wrote more than 100 books, mostly juvenile and historical titles with a Christian message.[21]

- Charles Lever (1806 – 1872), an Irish author, who adventure fiction was based in part of his own experience.

- Robert Maclauchlan Macdonald (1874 – 1942), a Scottish traveller, prospector, and a Fellow of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society who wrote juvenile fiction.[22]

- Bessie Marchant (1862 – 1941), who wrote adventure fiction featuring young female heroines.

- L. T. Meade (1844 – 1914), Elizabeth Thomasina Meade Smith, a prolific Irish writer of stories for girls.

- Mary Russell Mitford (1787 – 1855), an English author and dramatist who when young, had known Jane Austen.

- Mrs Molesworth (1839 – 1921), n English writer of children's stories, who also wrote adult novels under a pseudonym.

- Ruth Ogden (1853 – 1927), Fannie Ogden Ide, an American author of juvenile fiction.

- James Macdonald Oxley (1855 – 1907), a Canadian writer of juvenile fiction.

- D. H. Parry (1868 – 1950), David Harold Parry, who also wrote as Morton Pike and Captain Eilton Blacke, a prolific English writer of serial stories and other juvenile fiction, wrote for Chums from 1892 to 1935, from a family of painters and a painter himself, was an expert on the Napoleonic Wars.[23]

- Jessie Saxby (1842 – 1940), a Scottish suffragist, folklorist, and author of juvenile fiction.

- Evelyn Sharp (1869 – 1955), an English suffragist and an author, who was well known for her juvenile fiction.

- Helen Shipton (1857 – 1945), wrote children's fiction with a moral, almost exclusively for the SPCK, as well as some plays in later life.[24]

- Gordon Stables (1840 – 1910), a Scottish medical doctor in the Royal Navywho wrote boys' adventure fiction.

- H. de Vere Stacpoole (1863 – 1951), Henry De Vere Stacpoole, a prolific Irish author, now best known as the author of The Blue Lagoon.

- Edward Step (1855 – 1931), who wrote extensively on botany, zoology and mycology.

- Herbert Strang (1866 – 1958), a pair of writers producing adventure fiction for boys, both historical and modern-day.

- William Makepeace Thackeray (1811 – 1863), a British novelist, author and illustrator born in India, best known for Vanity Fair.

- Percy Westerman (1875 – 1959), a prolific author of boys' adventure fiction, many with military and naval themes.

- Frederick Whishaw (1854 – 1934), a Russian-born British historian, poet, musician, and author of juvenile fiction.

- Charlotte Mary Yonge (1823 – 1901), who became a Sunday School teacher aged seven and remained one for the next seventy one years, she wrote to promote her religious views.[25]

Examples

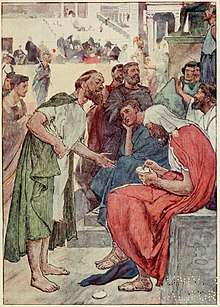

Colour illustration, which had always been used for books for small children, became more and more common for books for young adults, as the process got cheaper. Rainey illustrated Plutarch's lives for boys and girls : being selected lives freely retold (1900) by W. H. Weston with 16 full-page colour plates. Novels novels for juveniles usually had from four to twelve plates as can be seen from publisher's catalogues at the time,[26] anthologies, non-fiction books, and books for young children often had more.

Aristides and the Citizen

Aristides and the Citizen

Books written and illustrated

As well as the books he illustrated, Rainey also wrote and illustrated at least six books himself. Except where noted, the initial source of the following list is Kirkpatrick.[16]

| No. | Year | Title | Publisher | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1888 | All the Fun of the Fair | Ernest Nister, London | Paperback with coloured illustrations. 25 x 31 cm | Listed on Kirkpatrick as illustrator, but not as author.[27][13][28][29] |

| 2 | 1900 | Abdulla: The Mystery of an Ancient Papyrus | Wells Gardner, Darton & Co., London | 318 pages, 4 unnumbered leaves of plates : illustrations ; 20 cm | [29][30] |

| 3 | 1929 | The Last Voyage of the "Jane Ann" | Blackie & Son, London | 208 p., [4] leaves of plates : ill. ; 19 cm. | [29][30] |

| 4 | 1937 | The Lost "Reynolds" | Wells Gardner, Darton & Co., London | 308 pages | Serialised in John Erskine Clarke's Chatterbox in 1920[31][32] |

| 5 | 1938 | Who's on my side: A tale for boys | Wells Gardner, Darton & Co., London | 252 pages, octavo | [29][30] |

| 6 | 1938 | Admiral Rodney's Bantam Cock: A Story for boys | Wells Gardner, Darton & Co., London | 192p. 19 cm | [29] |

Later life

Rainey's wife died in Eastbourne in the second quarter of 1919.[33] The local newspaper recalled that Rainey had moved to Eastbourne about this time,[4] and it was the Eastbourne address that the War Office used in the correspondence about the Medals awarded to his son Victor.

Raines was walking on Grand Parade on the sea-front promenade at Eastborne on 24 January 1935 when he collapsed and died before a doctor could be called.[4] He was only a short distance from his home at Avonmore, 24 Granville Road.[note 6] His daughter Florence Harriet was the executor of his will. His estate was valued at just under £400.[34]

Pennell says that, in his work, Rainey united the best traditions of the old with the most modern developments.[35] Pennell also listed Rainey among those artists whose names, like their works, are household words and who have a power of rendering events of the day in a fashion unequalled elsewhere.[36]

Peppin stated that His delicate brush strokes reproduced well in both colour and halftone. She also noted that Thorpe considered him a great but unrecognised illustrator who was ‘never conventional in his designs, had a fine sense of character, and maintained the interest throughout the whole of the drawing.[10] Newbolt noted that Rainey He had a long and successful career as a book illustrator, which continued right up to the end of his life.[7] His obituary in stated that many a small boy who has gazed with speechless admiration at some new gift book has been unconsciously grateful to Mr Rainey, for a great deal of his early work was the illustrating of boys' books.[4]

Notes

- Rainey had five brothers and two sisters, all of whom died before him except for his brother Charles (1862 – 1941) and sister Frances Sarah.(1864 – 1938)

- There are two Parishes of St George the Martyr in London, but the other St George the Martyr, Southwark is south of the River Thames and therefore not in Middlesex as the marriage record states.

- It is not clear is this was one of the works that was purchased during Gill's trip to Britain to purchase art for Australian Museums. The Catalogue for the National Gallery of Victoria records this painting has having been selected by the Royal Academy. See Matthew C. Potter (21 December 2018). British Art for Australia, 1860–1953: The Acquisition of Artworks from the United Kingdom by Australian National Galleries. Taylor & Francis. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-429-75267-4. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- This was a magazine aimed at juveniles that had first carried many of Jules Verne, novels as serials

- This is apparently unrelated to Jock and his friend (1889), Blackie and Son, London by Cora Langton

- Avonmore is now a small block of flats.

References

- Payne, J. F.; Bevan, Michael (23 September 2004). "Rainey, George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Ancestry.com. "Gloucestershire Archives; Gloucester, England; Reference Numbers: P343 IN 1/9". Gloucestershire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754–1938. Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com.

- W. W. Wagstaffe (1894). "In Memoriam: George Rainey: his life, work, and character". St. Thomas's Hospital Reports. J.&A. Churchill and Sons. p. xxvi. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Death of Mr William Rainey". Eastbourne Gazette (Wednesday 29 January 1936): 13. 29 January 1936.

- Graves, Algernon (1906). "Rainey, William, R.I.: Painter". The Royal Academy of Arts: A completed Dictionary of Contributors and their work from its foundation in 1769 to 1904. VI: Oakes to Rymsdyk. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 230.

- Organising Committee (1909). "British Section: Living British Artists (Water Colour)". Franco-British Exhibition, London 1908. London: Bemrose and Sons Ltd. pp. 55, 61. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Newbolt, Peter (1996). "Appendix IV: Illustration and Design: Notes on Artists and Designers: Rainby, William, R.B.A., R.I., R.O.I., 1852–1936". G.A. Henty, 1832–1902 : a bibliographical study of his British editions, with short accounts of his publishers, illustrators and designers, and notes on production methods used for his books. Brookfield, Vt.: Scholar Press. p. 636. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Arrangement for this day". Morning Post (Tuesday 7 April 1891): 5. 7 April 1891.

- "General News". St James's Gazette (Thursday 26 November 1891): 7. 26 November 1891.

- Peppin, Bridget; Micklethwait, Lucy (1993). "William H. Rainey (1852–1936)". Dictionary of British book illustrators : the twentieth century. London: Murray. pp. 242–243. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Little, James Stanley (28 April 1932). "Local Art at the Spring Exhibitions: No 2. The Royal Institute". West Sussex Gazette (Thursday 28 April 1932): 6.

- "Eastbourne Artists at the Spring Exhibitions". Eastbourne Gazette (Wednesday 9 May 1934): 3. 9 May 1934.

- Houfe, Simon (1978). "Rainey, William RBA RI 1852–1936". Dictionary of British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists, 1800–1914. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 426. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Kirkpatrick, Robert J. (11 July 1905). "W. Rainey". The Men Who Drew For Boys (And Girls): 101 Forgotten Illustrators of Children's Books: 1844–1970. London: Robert J. Kirkpatrick. pp. 313–317.

- Kirkpatrick, Robert J. (24 February 2018). "W. Rainey". Bear Alley. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Kirkpatrick, Robert J. (11 July 1905). "Checklist of Books Illustrated by W. Rainey". The Men Who Drew For Boys (And Girls): 101 Forgotten Illustrators of Children's Books: 1844–1970. London: Robert J. Kirkpatrick. pp. 395–401.

- "Author:Helen Atteridge (born 1856)". At the Circulating Library: A database of Victorian Fiction 1837–1901. 31 December 2019.

- "Holly House and Ridges Row — May Baldwin". FictionDB. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Amy Le Feuvre Author Page". Curiosmith: Gospel Heritage Literature. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Kemp, Sandra; Mitchell, Charlotte; Trotter, David (1997). "Kenyon, Edith C. (d. 1925)". Edwardian Fiction: An Oxford Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 222.

- "Author: Emma Leslie (1838–1909) (real name Emma Boultwood)". At the Circulating Library: A database of Victorian Fiction 1837–1901. 31 December 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Macdonald, Robert M (1906). "How we found the Great Sectrum Opal". The Wide World Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly of True Narrative, Adventure, Travel, Customs and Sport ... A. Newnes, Limited. pp. 198–203. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Lofts, William Oliver Guillemont (1970). "Parry, David Harold". The Men Behind Boy's Fiction. London: Howard Baker. pp. 262–263. ISBN 0093047703. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- "Author: Helen Shipton (1857–1945)". At the Circulating Library: A database of Victorian Fiction 1837–1901. 31 December 2019. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Sutherland, John (1989). "Yonge, Charlotte Mary (1823–1901)". The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 685.

- Blackie and Son (1889). "Historic Tales by G. A. Henty, Story Books for Boys, Story Books for Girls". Blackie & Son's: Illustrated Story Books: 1889. London: Blackie and Son. pp. 1–24. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Kirk, John Foster (1891). "Rainey, W.". A Supplement To Allibone S Critical Dictionary Of English Literature British And American Authors Vol I. II. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company. p. 1260. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Tarrington Books. "All the Fun of the Fair: W. Rainey". Abe Books. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Search Results for author: Rainey, W. (William)". Library Hub Discover. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Search Results for 'au:Rainey, W.'". WorldCat.

- Rainey, William (1920). "The Lost Reynolds". Chatterbox: 2, 14, 18, 31, 34, 46, 50, 62, 66, 79, 82, 94, 98, 111, 118, 122, 135, 143, 146, 159, 162, 174, 178, 190, 194, 206, 210, 222, 226, 239, 242, 254, 258, 270, 274, 286, 290, 302, 306, 314. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- High Barn Books. "The Lost 'Reynolds': Rainey, William". Abe Books. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Wills and Probates 1858–1996: Pages for Rainey and Year of Death 1936". Find a Will Service. p. 12. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Pennell, Joseph (1894). Pen Drawing and Pen Draughtsmen: Their work and there methods: A study of the art to-day with technical suggestions (2nd. ed.). London: MacMillan and Co. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Pennell, Joseph. "English Illustration". Modern Illustration. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 108.

External links

- Works by William Rainey at Project Gutenberg

- Books illustrated by Rainey at the Hathi Trust.

- The Strand Volume 1 on Project Gutenberg

- Watercolour by Rainey at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia.

- scan of The Bell Buoy; or, the Story of the Mysterious Key (1897) by Frederic Morell Holmes at the British Library.