Art Gallery of South Australia

The Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), established as the National Gallery of South Australia in 1881, is located in Adelaide. It is the most significant visual arts museum in the Australian state of South Australia. It has a collection of almost 45,000 works of art, making it the second largest state art collection in Australia (after the National Gallery of Victoria). As part of North Terrace cultural precinct, the Gallery is flanked by the South Australian Museum to the west and the University of Adelaide to the east.

| |

| |

| Established | 1881 |

|---|---|

| Location | North Terrace, Adelaide, Australia |

| Type | Art gallery |

| Visitors | 780,000[1] |

| Director | Rhana Devenport[2] |

| Website | www |

As well as its permanent collection, which is especially renowned for its collection of Australian art, AGSA hosts the annual Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art known as Tarnanthi, displays a number of visiting exhibitions each year and also contributes travelling exhibitions to regional galleries. European (including British), Asian and North American art are also well represented in its collections.

History

Establishment

The South Australian Society of Arts, established in 1856 and oldest fine arts society still in existence, held Annual exhibitions in South Australian Institute rooms and advocated for a public art collection. In 1880 Parliament gave £2,000 to the Institute to start acquiring a collection and the National Gallery of South Australia was established in June 1881.[3] It was opened in two rooms of the public library (now the Mortlock Wing of the State Library), by Prince Albert Victor and Prince George. Most works on display were acquired through a government grant. In 1897, Sir Thomas Elder bequeathed £25,000 to the art gallery for the purchase of artworks.[4]

Buildings

In 1889 the gallery moved further east to the Jubilee Exhibition Building, and then to its present site in 1900, in a specially designed building (now the Elder Wing)[5] designed by architect Owen Smythe and built in Classical Revival style by Messrs Tudgeon. Originally built with an enclosed portico, a 1936 refurbishment and enlargement included a new facade with an open Doric portico.[4]

Major extensions in 1962 (including a three-storey air-conditioned addition on the northern side), 1979 (general refurbishment, in time for its centenary in 1981) and 1996 (large expansion) increased the gallery’s display, administrative and ancillary facilities further.[5][4][6]

The building is listed in the South Australian Heritage Register.[4]

As of 2019, the building houses 64kWh worth of battery storage as part of the Government of South Australia Storage Demonstration project, powered by three 7.5kW Selectronic inverters. This reduces the consumption of power from the state grid.[1]

Governance

In 1939, an act of parliament, the 1939 number 44 Libraries and Institutes Act, repealed the Public library, Museum and Art Gallery and Institutes Act and separated the Gallery from the Public Library (now the State Library), and Museum, established its own board and changed its name to the Art Gallery of South Australia.[7][5]

The Art Gallery Act 1939 was passed to provide for the control of the library. This has been amended several times since.[8][9]

In 1967 the National Gallery of South Australia changed its name to the Art Gallery of South Australia.[7]

From about 1996 until late 2018 Arts SA (later Arts South Australia) had responsibility for this and several other statutory bodies such as the Museum and the State Library, after which the functions were transferred to direct oversight by the Department of the Premier and Cabinet, Arts and Culture section.[10]

Collection

As of May 2019, the AGSA collection comprises almost 45,000 works of art.[11] Of the state galleries, only the National Gallery of Victoria is larger.[12] It attracts about 780,000 visitors each year.[1]

Australian art

The Gallery is renowned for its collections of Australian art, including Indigenous Australian and colonial art, from about 1800 onwards. The collection is strong in nineteenth-century works (including silverware and furniture) and in particular Australian Impressionist (often referred to as Heidelberg School) paintings. Its twentieth-century Modernist art collection includes the work of many female artists, and there is a large collection of South Australian art, which includes 2,000 drawings by Hans Heysen and a large collection of photographs.[13][14]

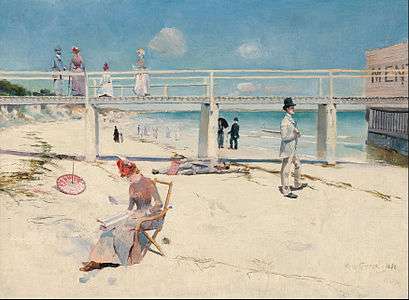

Heidelberg school works include Tom Roberts' A break away!, Charles Conder's A holiday at Mentone, and Arthur Streeton's Road to Templestowe.[6] The mid-twentieth century is represented by works by Russell Drysdale, Arthur Boyd, Margaret Preston, Bessie Davidson, and Sidney Nolan, and South Australian art includes works by James Ashton and Jeffrey Smart.

The Gallery became the first Australian gallery to acquire a work by an Indigenous artist in 1939, although systematic acquisition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art was not realised until the mid-1950s.[15] The Gallery and now holds a large and diverse collection of older and contemporary works, including the Kulata Tjuta collaboration created by Aṉangu artists working in the north of SA.[13]

International

European landscape paintings include works by Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael, Salomon van Ruysdael, Joseph Wright of Derby,[14] and Camille Pissarro.[16] Other European works include paintings by Goya, Francesco Guardi, Pompeo Batoni and Camille Corot.[14]

There is a large collection of British art, including many Pre-Raphaelite works, by artists Edward Burne-Jones, William Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Morris & Co.. Other works include John William Waterhouse's Circe Invidiosa (1892) and The Favourites of the Emperor Honorius (c.1883); William Holman Hunt's Christ and the Two Marys (1847) and The Risen Christ with the Two Marys in the Garden Of Joseph of Aramathea (1897); and John Collier's Priestess of Delphi (1891). Works by British portrait painters include Robert Peake, Anthony van Dyck, Peter Lely and Thomas Gainsborough.[14]

Sculpture includes works by Rodin, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Jacob Epstein[14] and Thomas Hirschhorn.[13]

The Asian art collection, begun in 1904, includes work from the whole region, with focuses on the pre-modern Japanese art, art of Southeast Asia, India and the Middle East. The Gallery holds Australia’s only permanent display of Islamic art.[13]

Exhibitions and collaborations

As well as its permanent collection, AGSA hosts the Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art,[17] displays a number of visiting exhibitions each year[18] and contributes travelling exhibitions to regional galleries.[19]

Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art

The Adelaide Biennial is "the only major biennial dedicated solely to presenting contemporary Australian art",[17] and also the longest-running exhibition featuring contemporary Australian art. It is supported by the Australia Council and other sponsors.[20] It is presented in association with the Adelaide Festival and staged by AGSA and partner gallery the Samstag Museum, as well as other venues such as the Adelaide Botanic Garden, Mercury Cinema and JamFactory.[21]

The Adelaide Biennial was established in 1990, planned to coincide with Artist's Week, which had commenced in 1982 to help counter the poor coverage of visual art in the Adelaide Festival of Arts programme at that time. The Art Gallery of New South Wales introduced an exhibition of Australian art called Australian Perspecta in 1981, which ran in alternate years with the international Biennale of Sydney, in response for the need for more forums focussing on Australian art.[22] In its first iteration in 1990, The Adelaide Biennale set out to emulate the Whitney Biennial of American art in New York City, and was intended to complement the Sydney Biennale and the Australian Perspecta exhibitions.[23] Then director Daniel Thomas said that they had introduced the Biennial to keep Australia up to date: the Festival attracts international and interstate visitors and it was a good time to introduce contemporary Australian art to this audience. Artists such as Fiona Hall, whose work is now in the National Gallery of Art, were showcased at the first Biennial. The exhibition today still projects Thomas' vision, with the most noticeable difference being that the current version has a theme and a catchy title.[22]

Selected events

The 2014 Biennial was titled "Dark Heart", an examination of changing national sensibilities, mounted by director Nick Mitzevitch, with 28 artists exhibiting.[24]

In 2016, the gallery participated in the large "Biennial 2016" art festival with its "Magic Object" exhibitions.[25]

In 2018, the title was "Divided Worlds", which aimed "...to describe the divide between ideas and ideologies, between geographies and localities, between communities and nations, and the subjective and objective view of experience and reality itself". Venues included the Museum of Economic Botany in Adelaide Botanic Garden.[26] It drew record crowds, with more than 240,000 people over a 93-day season under curator Erica Green.[27]

Curator for the 2020 Biennial, which was scheduled to run from 29 February to 8 June 2020, is Leigh Robb, inaugural Curator of Contemporary Art appointed in 2016.[27] The title is "Monster Theatres", examining "our relationships with each other, the environment and technology" and featuring a lot of live art. Paintings, photography, sculpture, textiles, film, video, sound art, installation, and performance art by 23 artists are featured, including work by Abdul Abdullah, Stelarc, David Noonan, Garry Stewart and Australian Dance Theatre,[28][29] Megan Cope, Karla Dickens, Julia Robinson, performance artist Mike Parr, Polly Borland, Willoh S. Weiland, Yhonnie Scarce (whose work In the Dead House was installed in the old Adelaide Lunatic Asylum morgue building in the Botanic Garen[30][31]) and others.[32] However, AGSA had to temporarily close from 25 March 2020 owing to the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, so some of the exhibits were shown online, along with virtual tours of the exhibition.[33] When the gallery reopened on 8 June, it was announced that the exhibition period would be extended to 2 August 2020. Some of the exhibits [34]

Tarnanthi

Since 2015, AGSA has hosted and supported events connected with Tarnanthi (pronounced tar-nan-dee), the Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art. The 2015 exhibition was said to be the "most ambitious exhibition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art in its 134-year history".[35] In association with the Government of South Australia and BHP, an expansive city-wide festival is staged biennially (in odd-numbered years), alternating with a focus exhibition at the gallery in the years in between.[36]

Other notable exhibitions

1906: The Light of the World

In 1906, when William Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World was on display, 18,168 visitors crammed through the gallery in less than two weeks to see it.[5]

Prizes

Ramsay Art Prize

In 2016, a new national $100,000 acquisitive art prize for artists, open to Australian artists under 40 working in any medium, was announced by the Premier of South Australia, Jay Weatherill. Supported by the James & Diana Ramsay Foundation, it is the country's richest art prize, awarded biennially. Chosen by an international judging panel, all finalists are exhibited in a major exhibition over the winter months at the Gallery.[37] There is also a non-acquisitive Lipman Karas People’s Choice Prize based on public vote, worth $15,000.[38][39]

2017

In its inaugural year, over 450 young artists submitted entries. From the 21 finalists selected for the exhibition, Perth-born artist Sarah Contos, now based in Sydney, won the prize for her entry entitled Sarah Contos Presents: The Long Kiss Goodbye.[38][40] Julie Fragar's 2016 painting Goose Chase: All of Us Together Here and Nowhere, which explores the story of Antonio de Fraga, her first paternal ancestor to emigrate to Australia in the 19th century, won the People's Choice Award.[41]

2019

In 2019, 23 finalists were chosen from a field of 350 submissions.[42][43] Vincent Namatjira won the main prize with his work Close Contact, 2018, a double-sided full-body representation of a man, in acrylic paint on plywood.[44][45] Winner of the People's Choice Prize was 24-year-old Zimbabwean man Pierre Mukeba (the youngest finalist) for his 3 metres (9.8 ft) by 4 metres (13 ft) painting entitled Ride to Church, inspired by childhood memories of the whole family perched somewhat precariously on a single motorbike to travel to church.[46]

Gallery

Selected Australian works

John Glover, A view of the artist's house and garden, in Mills Plains, Van Diemen's Land, 1835

John Glover, A view of the artist's house and garden, in Mills Plains, Van Diemen's Land, 1835 H. J. Johnstone, Evening shadows, backwater of the Murray, South Australia, 1880

H. J. Johnstone, Evening shadows, backwater of the Murray, South Australia, 1880

Tom Roberts, A break away!, 1891

Tom Roberts, A break away!, 1891

Selected international works

Hans Holbein the Younger (after), King Henry VIII, c. 1540

Hans Holbein the Younger (after), King Henry VIII, c. 1540 Joseph Wright of Derby, A view of Vesuvius from Posillipo, Naples, c. 1788

Joseph Wright of Derby, A view of Vesuvius from Posillipo, Naples, c. 1788 J. M. W. Turner, Alnwick Castle, 1829

J. M. W. Turner, Alnwick Castle, 1829 J. W. Waterhouse, Circe Invidiosa, 1892

J. W. Waterhouse, Circe Invidiosa, 1892

See also

References

- "Art Gallery of South Australia". Zen. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- AGSA: Our team

- Anderson, Margaret. "Art Gallery of South Australia". SA History Hub. History Trust of South Australia. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Art Gallery, North Terrace, 1926 (photograph)". SA Memory. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Art galleries". Adelaidia. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Barbara Cooper and Maureen Matheson, The World Museums Guide, McGraw-Hill, (1973) ISBN 9780070129252

- "National Gallery of South Australia (Record ID 36484115)". Libraries Australia. Libraries Australia Authorities - Full view. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "Art Galleries Act 1939, Version: 12.5.2011" (PDF). 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Art Gallery Act 1939". legislation.sa. Government of South Australia. Attorney-General's Dept. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- "About arts and culture". South Australia. Dept of the Premier and Cabinet. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Visit". Art Gallery of South Australia. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Adelaide: Art Gallery of SA Extensions". Architecture Australia. May–June 1996. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- "About the collection". AGSA. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Art Gallery of South Australia :: Collection". www.artgallery.sa.gov.au.

- "Our History". Art Gallery of South Australia.

- "Art Gallery of South Australia acquires $4.5 million French Impressionist painting". Australian Broadcasting Corporation News. 22 August 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- "Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art". Biennial Foundation. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "Art Gallery of South Australia: Exhibitions: Past Exhibitions". www.artgallery.sa.gov.au.

- AGSA Touring Exhibitions 2011 Archived 3 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art". AGSA. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "Venues". Biennial Foundation. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Llewellyn, Jane (15 November 2019). "Looking back on 30 years of the Adelaide Biennial". The Adelaide Review. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- North, Ian (December 1990). "A Critical Evaluation of the First Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art". Artlink. 10 (4). Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Mendelssohn, Joanna (4 March 2014). "The 2014 Adelaide Biennial: 'contemporary art as it was meant to be'". The Conversation. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Van der Walt, Annie (10 May 2016). "Biennial 2016: A Thread Runs Through It"". Adelaide Review. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Frost, Andrew (7 March 2018). "Adelaide Biennial of Australian art – a contemporary snapshot tackling big social issues". The Guardian.

- Nguyen, Justine (5 June 2018). "The 2018 Adelaide Biennial draws record crowds". Limelight Magazine. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Keen, Suzie (6 September 2019). "Monster 2020 Adelaide Biennial set to create a buzz". InDaily. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Marsh, Walter (6 September 2019). "Monster Theatres: 2020 Adelaide Biennial artists revealed". The Adelaide Review. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Adelaide Botanic Garden - former Lunatic Asylum Morgue". Adelaidepedia. 9 April 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Clark, Maddee (6 June 2020). "Yhonnie Scarce's art of glass". The Saturday Paper. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Jefferson, Dee (5 April 2020). "The monsters under the bed: Exhibition reveals our worst nightmares are those closest to home". ABC News. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "AGSA temporarily closes its doors to the public alongside SA cultural institutions". AGSA - The Art Gallery of South Australia. 28 February 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres". AGSA. 27 February 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "About the Festival". 2015 Tarnanthi. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "TARNANTHI: Our annual national celebration of contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art". Art Gallery of South Australia. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "Ramsay Art Prize: Media release" (PDF). 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dexter, John (26 May 2017). "Sarah Contos Wins Inaugural Ramsay Art Prize". Adelaide Review. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "Ramsay Art Prize". AGSA. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Coggan, Michael (26 May 2017). "Ramsay Art Prize won by artist Sarah Contos for quilt 'celebrating women in all their glory'". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "Julie Fragar - Ramsay Art Prize". Ramsay Art Prize. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- "$100,000 Ramsay Art Prize finalists announced for 2019" (pdf). AGSA. 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Marsh, Walter (30 April 2019). "Ramsay Art Prize 2019 finalists revealed". Adelaide Review. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "Ramsay Art Prize 2019". AGSA. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Smith, Matthew (24 May 2019). "Indigenous artist Vincent Namatjira wins the $100,000 Ramsay Art Prize". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Marsh, Walter. "Ramsay Art Prize finalist Pierre Mukeba named the people's favourite". Adelaide Review. Retrieved 9 August 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Further reading

- Thomas, Daniel (2011). "Art museums in Australia: a personal account". Understanding Museums. - Includes link to PDF of the article "Art museums in Australia: a personal retrospect" (originally published in Journal of Art Historiography, No 4, June 2011).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Art Gallery of South Australia. |