William M. Branham

William Marrion Branham (April 6, 1909 – December 24, 1965) was an American Christian minister and faith healer who initiated the post–World War II healing revival. He left a lasting impact on televangelism and the modern Charismatic movement and is recognized as the "principal architect of restorationist thought" for Charismatics by some Christian historians.[1][2] At the time they were held, his inter-denominational meetings were the largest religious meetings ever held in some American cities. Branham was the first American deliverance minister to successfully campaign in Europe; his ministry reached global audiences with major campaigns held in North America, Europe, Africa, and India.

William M. Branham | |

|---|---|

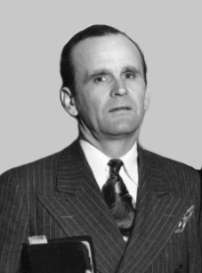

Branham in 1947 | |

| Born | William Marrion Branham April 6, 1909 |

| Died | December 24, 1965 (aged 56) Amarillo, Texas, US |

| Occupation | Evangelist |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Religion | Christianity

|

Branham claimed to have received an angelic visitation on May 7, 1946, commissioning his worldwide ministry and launching his campaigning career in mid-1946. His fame spread rapidly as crowds were drawn to his stories of angelic visitations and reports of miracles happening at his meetings. His ministry spawned many emulators and set in motion the broader healing revival that later became the modern Charismatic movement. From 1955, Branham's campaigning and popularity began to decline as the Pentecostal churches began to withdraw their support from the healing campaigns for primarily financial reasons. By 1960, Branham transitioned into a teaching ministry.

Unlike his contemporaries, who followed doctrinal teachings known as the Full Gospel tradition, Branham developed an alternate theology that was primarily a mixture of Calvinist and Arminian doctrines, and had a heavy focus on dispensationalism and Branham's own unique eschatological views. While widely accepting the restoration doctrine he espoused during the healing revival, his divergent post-revival teachings were deemed increasingly controversial by his Charismatic and Pentecostal contemporaries, who subsequently disavowed many of the doctrines as "revelatory madness".[3] Many of his followers, however, accepted his sermons as oral scripture and refer to his teachings as The Message. In 1963, Branham preached a sermon in which he indicated he was a prophet with the anointing of Elijah, who had come to herald Christ's second coming. Despite Branham's objections, some followers of his teachings placed him at the center of a cult of personality during his final years. Branham claimed to have made over one million converts during his career. His teachings continue to be promoted through the William Branham Evangelistic Association, who reported in 2018 that about 2 million people receive their material. Branham died following a car accident in 1965.

Early life

William M. Branham was born near Burkesville, Kentucky, on April 6, 1909,[4][5][6] the son of Charles and Ella Harvey Branham, the oldest of ten children.[7][lower-alpha 1] He claimed that at his birth, a "Light come [sic] whirling through the window, about the size of a pillow, and circled around where I was, and went down on the bed".[5] Branham told his publicist Gordon Lindsay that he had mystical experiences from an early age;[4] and that at age three he heard a "voice" speaking to him from a tree telling him "he would live near a city called New Albany".[4][5] According to Branham, that year his family moved to Jeffersonville, Indiana.[5] Branham also said that when he was seven years old, God told him to avoid smoking and drinking alcoholic beverages.[4][9] Branham stated he never violated the command.[4]

Branham's father was an alcoholic, and he grew up in "deep poverty" much like their neighbors.[4] As a child, he would often wear a coat held closed only by safety pins, without a shirt underneath.[6] Branham's neighbors reported him as "someone who always seemed a little different", but said he was a dependable youth.[4] His tendency towards "mystical experiences and moral purity" caused misunderstandings among his friends, family, and other young people; he was a "black sheep" from an early age.[10] Branham called his childhood "a terrible life."[9]

At 19, Branham left home seeking a better life. He traveled to Phoenix, Arizona, where he worked for two years on a ranch and began a successful career in boxing.[4] He returned to Jeffersonville when his brother died in 1929.[4][11] Branham had no experience with religion as a child; he said the first time he heard a prayer was at his brother's funeral.[12] Soon after, while working for the Public Service Company of Indiana, Branham was almost killed when he was overcome by gas.[12] While recovering from the accident, he said he again heard a voice leading him to begin seeking God.[12] He began attending a local Independent Baptist church, the First Pentecostal Baptist Church of Jeffersonville, where he converted to Christianity.[13][4] Six months later, he was ordained as an Independent Baptist minister.[4] His early ministry was an "impressive success"; he quickly attracted a small group of followers, who helped obtain a tent in which he could hold a revival.[4]

At the time of Branham's conversion, the First Pentecostal Baptist Church of Jeffersonville was a nominally Baptist church that observed some Pentecostal doctrines, including divine healing.[14] As a result, he may have been exposed to some Pentecostal teachings from his conversion.[15] He was first exposed to a Pentecostal denominational church in 1936, which invited him to join, but he refused.[14][lower-alpha 2]

During June 1933, Branham held revival meetings in his tent.[4] On June 2 that year, the Jeffersonville Evening News said the Branham campaign reported 14 converts.[17] His followers believed his ministry was accompanied by miraculous signs from its beginning, and that when he was baptizing converts on June 11, 1933, in the Ohio River near Jeffersonville, a bright light descended over him and that he heard a voice say, "As John the Baptist was sent to forerun the first coming of Jesus Christ, so your message will forerun His second coming".[18][19] Belief in the baptismal story is a critical element of faith among Branham's followers.[20] Branham initially interpreted this in reference to the restoration of the gifts of the spirit to the church and made regular references to the baptismal story from the earliest days of the healing revival.[21] In later years, Branham also connected the story to his teaching ministry.[22] Baptist historian Doug Weaver said Branham might have embellished the baptismal story when he was achieving success in the healing revival.[23]

Following his June tent meeting, Branham's supporters helped him organize a new church, the Branham Tabernacle, in Jeffersonville.[24] Branham served as pastor from 1933 to 1946.[24] The church flourished at first, but its growth began to slow. Because of the Great Depression, it was often short of funds, so Branham served without compensation.[24] Branham believed the stagnation of the church's growth was a punishment from God for his failure to embrace Pentecostalism.[24] Branham married Amelia Hope Brumbach (b. July 16, 1913) in 1934, and they had two children; William "Billy" Paul Branham (b. September 13, 1935) and Sharon Rose Branham (b. October 27, 1936).[7] Branham's wife died on July 22, 1937, and their daughter died four days later (July 26, 1937), shortly after the Ohio River flood of 1937.[25] Branham interpreted their deaths as God's punishment for his continued resistance to holding revivals for the Oneness Pentecostals.[18][lower-alpha 3]

Branham married Meda Marie Broy in 1941, and together they had three children; Rebekah (b. 1946), Sarah (b. 1950), and Joseph (b. 1955).[7]

Healing revival

Background

Branham is known for his role in the healing revivals that occurred in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s,[27] and most participants in the movement regarded him as its initiator.[28] Christian writer John Crowder described the period of revivals as "the most extensive public display of miraculous power in modern history".[29] Some, like Christian author and countercult activist Hank Hanegraaff, rejected the entire healing revival as a hoax and condemned the evangelical and Charismatic movements as cults.[30] Divine healing is a tradition and belief that was historically held by a majority of Christians but it became increasingly associated with Evangelical Protestantism.[31] The fascination of most of American Christianity with divine healing played a significant role in the popularity and inter-denominational nature of the revival movement.[32]

Branham held massive inter-denominational meetings, from which came reports of hundreds of miracles.[28] Historian David Harrell described Branham and Oral Roberts as the two giants of the movement and called Branham its "unlikely leader."[28]

Early campaigns

Branham held his first meetings as a faith healer in 1946.[33] His healing services are well documented, and he is regarded as the pacesetter for those who followed him.[34] At the time they were held, Branham's revival meetings were the largest religious meetings some American cities he visited had ever seen;[35] reports of 1,000 to 1,500 converts per meeting were common.[35] Historians name his June 1946 St. Louis meetings as the inauguration of the healing revival period.[36] He said he had received an angelic visitation on May 7, 1946, commissioning his worldwide ministry.[37] In his later years, in an attempt to link his ministry with the end time, he connected his vision with the establishment of the nation of Israel, at one point mistakenly stating the vision occurred on the same day.[38][38][lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5]

His first revival meetings were held over 12 days during June 1946 in St. Louis.[41] His first campaign manager, W. E. Kidston, was editor of The Apostolic Herald and had many contacts in the Pentecostal movement.[41] Kidston was instrumental in helping organize Branham's early revival meetings.[41] Time magazine reported on his St. Louis campaign meetings,[42] and according to the article, Branham drew a crowd of over 4,000 sick people who desired healing and recorded him diligently praying for each.[41] Branham's fame began to grow as a result of the publicity and reports covering his meetings.[41] Following the St. Louis meetings, Branham launched a tour of small Oneness Pentecostal churches across the Midwest and southern United States, from which stemmed reports of healing and one report of a resurrection.[41] By August his fame had spread widely. He held meetings that month in Jonesboro, Arkansas, and drew a crowd of 25,000 with attendees from 28 different states.[43] The size of the crowds presented a problem for Branham's team as they found it difficult to find venues that could seat large numbers of attendees.[43]

Branham's revivals were interracial from their inception and were noted for their "racial openness" during the period of widespread racial unrest.[44] An African American minister participating in the St. Louis meetings claimed to be healed during the revival, helping to bring Branham a sizable African American following from the early days of the revival. Dedicated to ministering to both races, Branham insisted on holding interracial meetings even in the southern states. To satisfy segregation laws when ministering in the south, Branham's team would use a rope to divide the crowd by race.[44]

After holding a very successful revival meeting in Shreveport during mid-1947, Branham began assembling an evangelical team that stayed with him for most of the revival period.[45] The first addition to the team was Jack Moore and Young Brown, who periodically assisted him in managing his meetings.[46] Following the Shreveport meetings, Branham held a series of meetings in San Antonio, Phoenix, and at various locations in California.[45] Moore invited his friend Gordon Lindsay to join the campaign team, which he did beginning at a meeting in Sacramento, California, in late 1947.[46] Lindsay was a successful publicist and manager for Branham, and played a key role in helping him gain national and international recognition.[47][48]In 1948, Branham and Lindsay founded Voice of Healing magazine, which was originally aimed at reporting Branham's healing campaigns.[47][lower-alpha 6] Lindsay was impressed with Branham's focus on humility and unity, and was instrumental in helping him gain acceptance among Trinitarian and Oneness Pentecostal groups by expanding his revival meetings beyond the United Pentecostal Church to include all of the major Pentecostal groups.[49][42]

The first meetings organized by Lindsay were held in northwestern North America during late 1947.[46][42] At the first of these meetings, held in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canadian minister Ern Baxter joined Branham's team.[46] Lindsay reported 70,000 attendees to the 14 days of meetings and long prayer lines as Branham prayed for the sick.[46] William Hawtin, a Canadian Pentecostal minister, attended one of Branham's Vancouver meetings in November 1947 and was impressed by Branham's healings. Branham thus became an influence on the Latter Rain revival movement, which Hawtin helped initiate.[50] In January 1948, meetings were held in Florida;[46] F. F. Bosworth met Branham at the meetings and also joined his team.[51] Bosworth was among the pre-eminent ministers of the Pentecostal movement and lent great weight to Branham's campaign team.[51] He remained a strong Branham supporter until his death in 1958.[51] Bosworth endorsed Branham as "the most sensitive person to the presence and working of the Holy Spirit" he had ever met.[52][53] During early 1947, a major campaign was held in Kansas City, where Branham and Lindsay first met Oral Roberts.[46] Roberts and Branham had contact at different points during the revival.[54] Roberts said Branham was "set apart, just like Moses".[54]

Branham spent many hours ministering and praying for the sick during his campaigns, and like many other leading evangelists of the time he suffered exhaustion.[55] After one year of campaigning, his exhaustion began leading to health issues.[56] Attendees reported seeing him "staggering from intense fatigue" during his last meetings.[46] Just as Branham began to attract international attention in May 1948, he announced that due to illness he would have to halt his campaign.[46][57] His illness shocked the growing movement,[58] and his abrupt departure from the field caused a rift between him and Lindsay over the Voice of Healing magazine.[46] Branham insisted that Lindsay take over complete management of the publication.[46] With the main subject of the magazine no longer actively campaigning, Lindsay was forced to seek other ministers to promote.[46] He decided to publicize Oral Roberts during Branham's absence, and Roberts quickly rose to prominence, in large part due to Lindsay's coverage.[51]

Branham partially recovered from his illness and resumed holding meetings in October 1948; in that month he held a series of meetings around the United States without Lindsay's support.[51] Branham's return to the movement led to his resumed leadership of it.[51] In November 1948, he met with Lindsay and Moore and told them he had received another angelic visitation, instructing him to hold a series of meetings across the United States and then to begin holding meetings internationally.[59] As a result of the meeting, Lindsay rejoined Branham's campaigning team.[59]

Style

Most revivalists of the era were flamboyant but Branham was usually calm and spoke quietly, only occasionally raising his voice.[54] His preaching style was described as "halting and simple", and crowds were drawn to his stories of angelic visitation and "constant communication with God".[28] He refused to discuss controversial doctrinal issues during the early years of his campaigns,[60][61] and issued a policy statement that he would only minister on the "great evangelical truths".[62] He insisted his calling was to bring unity among the different churches he was ministering to and to urge the churches to return to the roots of early Christianity.[54]

In the first part of his meetings, one of Branham's companion evangelists would preach a sermon.[46] Ern Baxter or F. F. Bosworth usually filled this role, but other ministers also participated in Branham's campaigns.[46] Baxter generally focused on bible teaching; Bosworth counseled supplicants on the need for faith and the doctrine of divine healing.[63] Following their build-up, Branham would take the podium and deliver a short sermon,[46] in which he usually related stories about his personal life experiences.[60] After completing his sermon, he would proceed with a prayer line where he would pray for the sick.[54] Branham would often request God to "confirm his message with two-or-three faith inspired miracles".[63] His campaign manager organized the prayer line, sending supplicants forward to be prayed for on stage individually.[63] Branham generally prayed for a few people each night and believed witnessing the results on the stage would inspire faith in the audience and permit them to experience similar results without having to be personally prayed for.[64] Describing Branham's method, Bosworth said "he does not begin to pray for the healing of the afflicted in body in the healing line each night until God anoints him for the operation of the gift, and until he is conscious of the presence of the Angel with him on the platform. Without this consciousness he seems to be perfectly helpless."[65]

Branham told audiences the angel that commissioned his ministry had given him two signs by which they could prove his commission.[65] He described the first sign as vibrations he felt in his hand when he touched a sick person's hand, which communicated to him the nature of the illness, but did not guarantee healing.[65][66] Branham's use of what his fellow evangelists called a word of knowledge gift separated him from his contemporaries.[33][60] This second sign did not appear in his campaigns until after his recovery in 1948, and was used to "amaze tens of thousands" at his meetings.[60] According to Bosworth, this gift of knowledge allowed Branham "to see and enable him to tell the many events of [people's] lives from their childhood down to the present".[60][67] This caused many in the healing revival to view Branham as a "seer like the old testament prophets".[60] Branham amazed even fellow evangelists, which served to further push him into a legendary status in the movement.[60] Branham's audiences were often awestruck by the events during his meetings.[54][68] At the peak of his popularity in the 1950s, Branham was widely adored and "the neo-Pentecostal world believed Branham to be a prophet to their generation".[53]

Opposition

Branham faced criticism and opposition from the early days of the healing campaign.[69] According to historian Ronald Kydd, Branham evoked strong opinions from people with whom he came into contact; "most people either loved him or hated him".[70][71] In 1947, Rev. Alfred Pohl, a minister in Saskatchewan, Canada, stated that many people Branham pronounced as healed later died.[69] A year later, W. J. Taylor, a district superintendent with the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada, raised the same concern and asked for a thorough investigation.[72] Taylor presented evidence that claims of the number of people healed were vastly overestimated.[61] He stated, "there is a possibility that this whole thing is wrong".[73][72] The number of people who claimed to be healed in Branham's campaign meetings "is impossible to approximate" and the numbers vary greatly between sources.[74] According to Kydd, by watching films of the revival meetings, "the viewer would assume almost everyone was healed" but the results proved otherwise the few times follow-up was made.[75] No consistent record of follow-ups was made, making analysis of the claims difficult to subsequent researchers.[75] Pentecostal historian Walter Hollenweger said, "very few were actually healed".[76] Some attendees of Branham's meetings believed the healings were a hoax and accused him of selectively choosing who could enter the prayer line.[77] Some people left his meetings disappointed after finding Branham's conviction that everyone in the audience could be healed without being in the prayer line proved incorrect.[77] Branham generally attributed the failure of supplicants to receive healing to their lack of faith.[78]

The "word of knowledge" gift was likewise subject to much criticism.[70] Hollenweger investigated Branham's use of the "word of knowledge gift" and found no instances in which Branham was mistaken in his often-detailed pronouncements.[70] Criticism of Branham's use of this gift was primarily around its nature; some accused him of witchcraft and telepathy.[75] Branham was openly confronted with such criticisms and rejected the assertions.[75]

Growing fame

In January 1950, Branham's campaign team held their Houston campaign, one of the most significant series of meetings of the revival.[51] The location of their first meeting was too small to accommodate the approximately 8,000 attendees, and they had to relocate to the Sam Houston Coliseum.[51] On the night of January 24, 1950, Branham was photographed during a debate between Bosworth and local Baptist minister W. E. Best regarding the theology of divine healing.[79][59] Bosworth argued in favor, while Best argued against.[79] The photograph showed a light above Branham's head, which he and his associates believed to be supernatural.[79][59] The photograph became well-known in the revival movement and is regarded by Branham's followers as an iconic relic.[72] Branham believed the light was a divine vindication of his ministry;[79] others believed it was a glare from the venue's overhead lighting.[80]

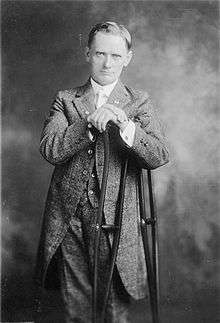

In January 1951, US Congressman William Upshaw, who had been crippled for 59 years as the result of an accident, said he was miraculously healed and had regained the ability to walk in a Branham meeting, further fueling Branham's fame.[72] Upshaw sent a letter describing his healing claim to each member of Congress.[81][72] Among the widespread media reports was a story in the Los Angeles Times that described it as "perhaps the most effective healing testimony this generation has ever seen".[81] Upshaw died in November 1952, at the age of 86.[82]

Branham's meetings were regularly attended by journalists,[83] who wrote articles about the miracles reported by Branham and his team throughout the years of his revivals, and claimed patients were cured of various ailments after attending prayer meetings with Branham.[83] Durban Sunday Tribune and The Natal Mercury reported wheelchair-bound people rising and walking.[84][85] Winnipeg Free Press reported a girl was cured of deafness.[86] El Paso Herald-Post reported hundreds of attendees at one meeting seeking divine healing.[87] Logansport Press reported a father's claim that his four-year-old son, who suffered from a "rare brain ailment", benefited from Branham's meetings.[88] Despite such occasional glowing reports, most of the press coverage Branham received was negative.[89]

According to Hollenweger, "Branham filled the largest stadiums and meeting halls in the world" during his five major international campaigns.[59][89] Branham held his first series of campaigns in Europe during April 1950 with meetings in Finland, Sweden, and Norway.[90][59] Attendance at the meetings generally exceeded 7,000 despite resistance to his meetings by the state churches.[62] In Norway, the Directorate of Health forbade Branham from laying hands on the sick and sent police to his meetings to enforce the order.[91] Branham was the first American deliverance minister to successfully tour in Europe.[92] A 1952 campaign in South Africa had the largest attendance in Branham's career, with an estimated 200,000 attendees.[62][93] According to Lindsay, the altar call at his Durban meeting received 30,000 converts.[62] During international campaigns in 1954, Branham visited Portugal, Italy, and India.[62] Branham's final major overseas tour in 1955 included visits to Switzerland and Germany.[94]

Financial difficulties

In 1955, Branham's campaigning career began to slow following financial setbacks.[53][95] Even after he became famous, Branham continued to wear inexpensive suits and refused large salaries; he was not interested in amassing wealth as part of his ministry[6] and was reluctant to solicit donations during his meetings.[96] During the early years of his campaigns, donations had been able to cover costs, but from 1955, donations failed to cover the costs of three successive campaigns,[53] one of which incurred a $15,000 deficit.[95] Some of Branham's business associates thought he was partially responsible because of his lack of interest in the financial affairs of the campaigns and tried to hold him personally responsible for the debt.[53] Branham briefly stopped campaigning and said he would have to take a job to repay the debt, but the Full Gospel Business Men's Fellowship International ultimately offered financial assistance to cover the debt.[96] Branham became increasingly reliant on the Full Gospel Businessmen to finance his campaign meetings as the Pentecostal denominations began to withdraw their financial support.[96]

Finances became an issue again in 1956 when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) charged Branham with tax evasion.[53] The American government targeted the other leading revivalists with lawsuits during the same time period, including Oral Roberts, Jack Coe, and A. A. Allen.[97] The IRS asserted income reported by the ministers as non-taxable gifts was taxable,[95] despite the fact Branham had not kept the gifts for himself.[98] Except Allen, who won his legal battle, the evangelists settled their cases out of court.[95] The IRS investigation showed Branham did not pay close attention to the amount of money flowing through his ministry.[99] It also revealed that others were taking advantage of him.[99] Branham's annual salary was $7,000 while his manager's was $80,000.[95] Oral Roberts earned a salary of $15,000 in the same years.[100] The case was eventually settled out of court with the payment of a $40,000 penalty.[53][101] Branham was never able to completely pay off the debt.[53][101] Amid the financial issues, Lindsay left Branham's campaign team. Branham eventually criticized the Voice of Healing magazine as a "massive financial organization" that put making money ahead of promoting good.[58]

End of the revival

By the mid-1950s, dozens of the ministers associated with Branham and his campaigns had launched similar healing campaigns.[102] In 1956, the healing revival reached its peak, as 49 separate evangelists held major meetings.[103] Through the Voice of Healing magazine, Branham and Lindsay ineffectively attempted to discourage their activities by saying Branham wished they would help their local churches rather than launch national careers.[102] The swelling number of competitors and emulators further reduced attendance at Branham's meetings.[102] His correspondence also decreased sharply; whereas he had once received "a thousand letters a day", his mail dropped to 75 letters a day but Branham thought the decline was temporary.[104] He continued expecting something greater, which he said "nobody will be able to imitate".[102] In 1955, he reported a vision of a renewed tent ministry and a "third pull which would be dramatically different" than his earlier career.[102]

Among Branham's emulators was Jim Jones, the founder and leader of the Peoples Temple.[105] According to Historian Catherine Wessinger, while rejecting Christianity as a false religion, Jones covertly used popular Christian figures to advance his own ideology.[106] To draw the crowds he was seeking, Jones needed a religious headliner and invited Branham to share the platform with him at a self-organized religious convention held at the Cadle Tabernacle auditorium in Indianapolis from June 11 to 15, 1956.[105] Branham critics Peter Duyzer and John Collins reported that Branham "performed numerous miracles", drawing a crowd of 11,000.[107] Jones later became known for the mass murder and suicide at Jonestown in November 1978.[105] According to Collins, Jim Jones and Paul Schäfer were influenced to move to South America by Branham's 1961 prophecy concerning Armageddon, but ultimately concluded that Jones and Branham "did not see eye to eye", and that Jones rejected Branham as a dishonest person.[108][109][lower-alpha 7]

By 1960, the number of evangelists holding national campaigns dropped to 11.[103] Several perspectives on the decline of the healing revival have been offered. Crowder suggested Branham's gradual separation from Gordon Lindsay played a major part in the decline.[111] Harrell attributed the decline to the increasing number of evangelists crowding the field and straining the financial resources of the Pentecostal denominations.[102] Weaver agreed Pentecostal churches gradually withdrew their support for the healing revival, mainly over the financial stresses put on local churches by the healing campaigns.[112] The Assemblies of God were the first to openly withdraw support from the healing revival in 1953.[112] Weaver pointed to other factors that may have helped destroy the initial ecumenism of the revival; tension between the independent evangelists and the Pentecostal churches caused by the evangelists' fund-raising methods, denominational pride, sensationalism, and doctrinal conflicts—particularly between the Oneness and Trinitarian factions within Pentecostalism.[112]

Later life

Teaching ministry

As the healing revival began to wane, many of Branham's contemporaries moved into the leadership of the emerging Charismatic movement, which emphasized use of spiritual gifts.[95] The Charismatic movement is a global movement within both Protestant and non-Protestant Christianity that supports the adoption of traditionally Pentecostal beliefs, especially the spiritual gifts (charismata). The movement began in the teachings of the healing revival evangelists and grew as their teachings came to receive broad acceptance among millions of Christians.[113] At the same time the Charismatic movement was gaining broad acceptance, Branham began to transition to a teaching ministry. He began speaking on the controversial doctrinal issues he had avoided for most of the revival.[114] By the 1960s, Branham's contemporaries and the Pentecostal denominations that had supported his campaigns regarded him as an extremely controversial teacher.[115] The leadership of the Pentecostal churches pressed Branham to resist his urge to teach and to instead focus on praying for the sick.[116] Branham refused, arguing that the purpose of his healing ministry was to attract audiences and, having thus been attracted, it was time to teach them the doctrines he claimed to have received through supernatural revelation.[117] Branham argued that his entire ministry was divinely inspired and could not be selectively rejected or accepted, saying, "It's either all of God, or none of God".[116]

At first, Branham taught his doctrines only within his own church at Jeffersonville, but beginning in the 1960s he began to preach them at other churches he visited.[116] His criticisms of Pentecostal organizations, and especially his views on holiness and the role of women, led to his rejection by the growing Charismatic movement and the Pentecostals from whom he had originally achieved popularity.[118] Branham acknowledged their rejection and said their organizations "had choked out the glory and Spirit of God".[118] As a result of their view of his teachings, many Pentecostals judged that Branham had "stepped out of his anointing" and had become a "bad teacher of heretical doctrine".[119]

Despite his rejection by the growing Charismatic movement, Branham's followers became increasingly dedicated to him during his later life; some even claimed he was the Messiah.[120] Branham quickly condemned their belief as heresy and threatened to stop ministering, but the belief persisted.[120] Many followers moved great distances to live near his home in Jeffersonville and, led by Leo Mercer, subsequently set up a colony in Arizona following Branham's move to Tucson in 1962.[120] Branham lamented Mercer and the actions of his group as he worried that a cult was potentially being formed among his most fanatical followers.[120]

Branham continued to travel to churches and preach his doctrine across North America during the 1960s. He held his final set of revival meetings in Shreveport at the church of his early campaign manager Jack Moore in November 1965.[121]

Teachings

Branham developed a unique theology and placed emphasis on a few key doctrines, including his eschatological views, annihilationism, oneness of the Godhead, predestination, eternal security, and the serpent's seed.[122] His followers refer to his teachings collectively as "The Message".[123] Kydd and Weaver have both referred to Branham's teachings as "Branhamology".[124][123] Most of Branham's teachings have precedents within sects of the Pentecostal movement or in other non-Pentecostal denominations.[125] The doctrines Branham imported from non-Pentecostal theology and the unique combination of doctrines that he created as a result led to widespread criticism from Pentecostal churches and the Charismatic movement.[125][126] His unique arrangement of doctrines, coupled with the highly controversial nature of the serpent seed doctrine, caused the alienation of many of his former supporters.[125][126][127]

The Full Gospel tradition, which has its roots in Wesleyan Arminianism, is the theology generally adhered to by the Charismatic movement and Pentecostal denominations.[123] Branham's doctrines are a blend of both Calvinism and Arminianism, which are considered contradictory by many theologians.[128] As a result, his theology seemed complicated and bizarre to many people who admired him personally during the years of the healing revival.[126] Many of his followers regard his sermons as oral scripture and believe Branham had rediscovered the true doctrines of the early church.[123]

Divine healing

Throughout his ministry, Branham taught a doctrine of faith healing that was often the central teaching he espoused during the healing campaign.[129] He believed healing was the main focus of the ministry of Jesus Christ and believed in a dual atonement; "salvation for the soul and healing for the body".[129] He believed and taught that miracles ascribed to Christ in the New Testament were also possible in modern times.[129] Branham believed all sickness was a result of demonic activity and could be overcome by the faith of the person desiring healing.[129] Branham argued that God was required to heal when faith was present.[129] This led him to conclude that individuals who failed to be healed lacked adequate faith.[129] Branham's teaching on divine healing were within the mainstream of Pentecostal theology and echoed the doctrines taught by Smith Wigglesworth, Bosworth, and other prominent Pentecostal ministers of the prior generation.[129]

Annihilationism

Annihilationism, the doctrine that the damned will be totally destroyed after the final judgment so as to not exist, was introduced to Pentecostalism in the teachings of Charles Fox Parham (1873–1929).[130] Not all Pentecostal sects accepted the idea.[131] Prior to 1957, Branham taught a doctrine of eternal punishment in hell.[132] By 1957 he began promoting an annihilationist position in keeping with Parham's teachings.[130] He believed that "eternal life was reserved only for God and his children".[130] In 1960, Branham claimed the Holy Spirit had revealed this doctrine to him as one of the end-time mysteries.[133] Promoting annihilationism led to the alienation of Pentecostal groups that had rejected Parham's teaching on the subject.[133]

Godhead

Like other doctrines, the Godhead formula was a point of doctrinal conflict within Pentecostalism.[133] As Branham began offering his own viewpoint, it led to the alienation of Pentecostal groups adhering to Trinitarianism.[133] Branham shifted his theological position on the Godhead during his ministry.[133] Early in his ministry, Branham espoused a position closer to an orthodox Trinitarian view.[133] By the early 1950s, he began to privately preach the Oneness doctrine outside of his healing campaigns.[133] By the 1960s, he had changed to openly teaching the Oneness position, according to which there is one God who manifests himself in multiple ways; in contrast with the Trinitarian view that three distinct persons comprise the Godhead.[115]

Branham came to believe that trinitarianism was tritheism and insisted members of his congregation be re-baptized in Jesus's name in imitation of Paul the Apostle.[134] Branham believed his doctrine had a nuanced difference from the Oneness doctrine and to the end of his ministry he openly argued that he was not a proponent of Oneness doctrine.[134] He distinguished his baptismal formula from the Oneness baptism formula in the name of Jesus by teaching that the baptismal formula should be in the name of Lord Jesus Christ.[134] He argued that there were many people named Jesus but there is only one Lord Jesus Christ.[134] By the end of his ministry, his message required an acceptance of the oneness of the Godhead and baptism in the name of Lord Jesus Christ.[128]

Predestination

Branham adopted and taught a Calvinistic form of the doctrine of predestination and openly supported Calvin's doctrine of Eternal Security, both of which were at odds with the Arminian view of predestination held by Pentecostalism.[128] Unlike his views on the Godhead and Annihilationism, there was no precedent within Pentecostalism for his views on predestination, and opened him to widespread criticism.[134] Branham lamented that more so than any other teaching, Pentecostals criticized him for his predestination teachings.[135] Branham believed the term "predestination" was widely misunderstood and preferred to use the word "foreknowledge" to describe his views.[135]

Opposition to modern culture

As Branham's ministry progressed, he increasingly condemned modern culture.[116] According to Weaver, Branham's views on modern culture were the primary reason the growing Charismatic movement rejected him; his views also prevented him from following his contemporaries who were transitioning from the healing revival to the new movement.[116] He taught that immoral women and education were the central sins of modern culture and were a result of the serpent's seed.[136] Branham viewed education as "Satan's snare for intellectual Christians who rejected the supernatural" and "Satan's tool for obscuring the 'simplicity of the Message and the messenger'".[136] Weaver wrote that Branham held a "Christ against Culture" opinion,[136] according to which loyalty to Christ requires rejection of non-Christian culture; an opinion not unique to Branham.[137]

Pentecostalism inherited the Wesleyan doctrine of entire sanctification and outward holiness from its founders, who came from Wesleyan-influenced denominations of the post-American Civil War era.[138] The rigid moral code associated with the holiness movement had been widely accepted by Pentecostals in the early twentieth century.[115][139] Branham's strict moral code echoed the traditions of early Pentecostalism[140] but became increasingly unpopular because he refused to accommodate mid-century Pentecostalism's shifting viewpoint.[115] He denounced cigarettes, alcohol, television, rock and roll, and many forms of worldly amusement.[141]

Branham strongly identified with the lower-class roots of Pentecostalism and advocated an ascetic lifestyle.[141] When he was given a new Cadillac, he kept it parked in his garage for two years out of embarrassment.[141] Branham openly chastised other evangelists, who seemed to be growing wealthy from their ministries and opposed the prosperity messages being taught.[141] Branham did not view financial prosperity as an automatic result of salvation.[141] He rejected the prosperity gospel that originated in the teachings of Oral Roberts and A. A. Allen.[141] Branham condemned any emphasis on expensive church buildings, elaborate choir robes, and large salaries for ministers, and insisted the church should focus on the imminent return of Christ.[141][142]

Branham's opposition to modern culture emerged most strongly in his condemnation of the "immorality of modern women".[141] He taught that women with short hair were breaking God's commandments and according to Weaver, "ridiculed women's desire to artificially beautify themselves with makeup".[143] Branham believed women were guilty of committing adultery if their appearance was intended to motivate men to lust, and viewed a woman's place as "in the kitchen".[143] Citing the creation story in which Eve is taken from Adam's side, Branham taught that woman was a byproduct of man.[140] According to Weaver, "his pronouncements with respect to women were often contradictory" and he regularly offered glowing praise of women.[140] Weaver stated that Branham "once told women who wore shorts not to call themselves Christians" but qualified his denunciations by affirming that obedience to the holiness moral code was not a requirement for salvation.[140] Branham did not condemn women who refused the holiness moral code to Hell, but he insisted they would not be part of the rapture.[140]

Weaver wrote that Branham's attitude to women concerning physical appearance, sexual drive, and marital relations was misogynistic,[144] and that Branham saw modern women as "essentially immoral sexual machines who were to blame for adultery, divorce and death. They were the tools of the Devil."[136] Some of Branham's contemporaries accused him of being a "woman hater", but he insisted he only hated immorality.[140] According to Edward Babinski, women who follow the holiness moral code Branham supported regard it as "a badge of honor".[145]

Serpent's seed

Branham taught an unorthodox doctrine of the source of original sin.[125] He believed the story of the fall of man in the Garden of Eden is allegorical and interpreted it to mean the serpent had sexual intercourse with Eve and that their offspring was Cain.[125] Branham taught that Cain's modern descendants were masquerading as educated people and scientists,[146] and that Cain's descendants were "a big religious bunch of illegitimate bastard children"[147][67] who comprised the majority of society's criminals.[148] He believed the serpent was the missing link between the chimpanzee and man, and speculated that the serpent was possibly a human-like giant.[149] Branham held the belief that the serpent was transformed into a reptile after it was cursed by God.[149] Weaver commented on Branham's interpretation of the story; "Consequently every woman potentially carried the literal seed of the devil".[140]

Branham first spoke about original sin in 1958; he rejected the orthodox view of the subject and hinted at his own belief in a hidden meaning to the story.[150] In later years, he made his opinion concerning the sexual nature of the fall explicitly known.[150] Weaver wrote that Branham may have become acquainted with serpent's seed doctrine through his Baptist roots; Daniel Parker, an American Baptist minister from Kentucky, promulgated a similar doctrine in the mid-1800s.[147] According to Pearry Green, Branham's teaching on the serpent's seed doctrine was viewed by the broader Pentecostal movement as the "filthy doctrine ... that ruined his ministry".[150] No other mainstream Christian group held a similar view; Branham was widely criticized for spreading the doctrine.[150] His followers view the doctrine as one of his greatest revelations.[150]

Eschatology

In 1960, Branham preached a series of sermons on the seven church ages based on chapters two and three of the Book of Revelation. The sermons closely aligned with the teachings of C. I. Scofield and Clarence Larkin, the leading proponents of dispensationalism in the preceding generation.[151] Like Larkin and Scofield, Branham said each church represents a historical age, and taught that the angel of each age was a significant church figure.[152] The message included the description of a messenger to the Laodicean Church age, which Branham believed would immediately precede the rapture.[152] Branham explained the Laodicean age would be immoral in a way comparable to Sodom and Gomorrah, and it would be a time in which Christian denominations rejected Christ.[153] As described by Branham, the characteristics of the Laodicean age resemble those of the modern era.[152] Branham described the characteristics of the Laodicean messenger by comparing his traits to Elijah and John the Baptist. He asserted the messenger would be a mighty prophet who put the Word of God first, that he would be a lover of the wilderness, that he would hate wicked women, and be an uneducated person.[154] Branham claimed the messenger to this last age would come in the spirit of Elijah the prophet and cited the Book of Malachi 4:5–6 (3:23–24 in Hebrew) as the basis for claiming the Elijah spirit would return.[145] His belief in a "seventh church age messenger" came from his interpretation of the Book of Revelation 3:14–22.[119][155][145][156]

Branham preached another sermon in 1963, further indicating he was a prophet who had the anointing of Elijah and was a messenger heralding the second coming of Christ.[115][157] Branham did not directly claim to be the end-time messenger in either of his sermons.[158][148] Weaver believed Branham desired to be the eschatological prophet he was preaching about,[158] but had self-doubt.[159] Branham left the identity of the messenger open to the interpretation of his followers, who widely accepted that he was that messenger.[159]

Branham regarded his 1963 series of sermons on the Seven Seals as a highlight of his ministry.[160] According to Weaver, they were primarily "a restatement of the dispensationalism espoused in the sermons on the seven church ages".[161] The sermons focused on the Book of Revelation 6:1–17, and provided an interpretation of the meaning of each of the seals.[160] Branham claimed the sermons were inspired through an angelic visitation.[160]

Anti-denominationalism

Branham believed denominationalism was "a mark of the beast", which added to the controversy surrounding his later ministry.[136][115][lower-alpha 8] Branham was not opposed to organizational structures; his concern focused on the "road block to salvation and spiritual unity" he believed denominations created by emphasizing loyalty to their organizations.[136]

Branham's doctrine was similar to the anti-Catholic rhetoric of classical Pentecostalism and Protestantism, which commonly associated the mark of the beast with Catholicism.[162] Branham, though, uniquely associated the image of the beast with Protestant denominations.[163] In his later years, he came to believe all denominations were "synagogues of Satan".[132] A key teaching of Branham's message was a command to true Christians to "come out" of the denominations and accept the message of the Laodicean messenger, who had the "message of the hour".[164] He argued that continued allegiance to a denomination was an acceptance of the mark of the beast, which would mean missing the rapture.[164]

Prophecies

Branham issued a series of prophecies during his ministry. He claimed to have had a prophetic revelation in June 1933 that predicted seven major events would occur before the Second Coming of Christ.[22] His followers believe he predicted several events, including the 1937 Ohio River Flood.[5] In 1964, Branham said judgement would strike the west coast of the United States and that Los Angeles would sink into the ocean; his most dramatic prediction.[120] Following both the 1933 and 1964 prophecies, Branham predicted the rapture would happen by 1977 and would be preceded by various worldwide disasters, the unification of denominational Christianity, and the rise-to-power of the Roman Catholic Pope.[145] Peter Duyzer, among other of Branham's critics, wrote that either none of Branham's prophecies came true or that they were all made after the fact.[165] Weaver wrote that Branham tended to embellish his predictions over time.[166][lower-alpha 9] Branham's followers believe his prophecies came true, or will do so in the future.[161]

Restorationism

Of all of Branham's doctrines, his teachings on Christian restorationism have had the most lasting impact on modern Christianity.[168] Charismatic writer Michael Moriarty described his teachings on the subject as "extremely significant" because they have "impacted every major restoration movement since".[169] As a result, Moriarty concluded Branham has "profoundly influenced" the modern Charismatic movement.[170] Branham taught the doctrine widely from the early days of the healing revival, in which he urged his audiences to unite and restore a form of church organization like the primitive church of early Christianity.[168] The teaching was accepted and widely taught by many of the evangelists of the healing revival, and they took it with them into the subsequent Charismatic and evangelical movements. Paul Cain, Bill Hamon, Kenneth Hagin, and other restoration prophets cite Branham as a major influence; they played a critical role in introducing Branham's restoration views to the Apostolic-Prophetic Movement, the Association of Vineyard Churches, and other large Charismatic organizations.[168] The Toronto Blessing, the Brownsville Revival, and other nationwide revivals of the late 20th century have their roots in Branham's restorationist teachings.[168]

The teaching holds that Christianity should return to a form mirroring the primitive Christian church.[168] It supports the restoration of apostles and prophets, signs and wonders, spiritual gifts, spiritual warfare, and the elimination of non-primitive features of modern Christianity.[168] Branham taught that by the end of the first century of Christianity, the church "had been contaminated by the entrance of an antichrist spirit".[169] As a result, he believed that from a very early date, the church had stopped following the "pure Word of God" and had been seduced into a false form of Christianity.[169] He stated the corruption came from the desire of early Christianity's clergy to obtain political power, and as a result became increasingly wicked and introduced false creeds.[169] This led to denominationalism, which he viewed as the greatest threat to true Christianity.[169] Branham viewed Martin Luther as the initiator of a process that would result in the restoration of the true form of Christianity, and traced the advancement of the process through other historic church figures.[171] He believed the rapture would occur at the culmination of this process.[171] Although Branham referred in his sermons to the culmination of the process as a future event affecting other people, he believed he and his followers were fulfilling his restoration beliefs.[3]

Death

On December 18, 1965, Branham and his family—except his daughter Rebekah—were returning to Jeffersonville, Indiana, from Tucson for the Christmas holiday.[121] About three miles (4.8 km) east of Friona, Texas, and about seventy miles (110 km) southwest of Amarillo on US Highway 60, just after dark, a car driven by a drunken driver traveling westward in the eastbound lane collided head-on with Branham's car.[172] He was rushed to the hospital in Amarillo where he remained comatose for several days and died of his injuries on Christmas Eve, December 24, 1965.[126][120][76]

Branham's death stunned the Pentecostal world and shocked his followers.[121] His funeral was held on December 29, 1965,[121] but his burial was delayed until April 11, 1966; Easter Monday.[121] Most eulogies only tacitly acknowledged Branham's controversial teachings, focusing instead on his many positive contributions and recalled his wide popularity and impact during the years of the healing revival.[173] Gordon Lindsay's eulogy stated that Branham's death was the will of God and privately he accepted the interpretation of Kenneth E. Hagin, who claimed to have prophesied Branham's death two years before it happened. According to Hagin, God revealed that Branham was teaching false doctrine and God was removing him because of his disobedience.[173][174][76]

In the confusion immediately following Branham's death, expectations that he would rise from the dead developed among his followers.[175] Most believed he would have to return to fulfill a vision he had regarding future tent meetings.[175] Weaver attributed the belief in Branham's imminent resurrection to Pearry Green, though Green denied it.[176] Even Branham's son Billy Paul seemed to expect his father's resurrection and indicated as much in messages sent to Branham's followers, in which he communicated his expectation for Easter 1966.[176] The expectation of his resurrection remained strong into the 1970s, in part based on Branham's prediction that the rapture could occur by 1977.[177] After 1977, some of his followers abandoned his teachings.[177][76]

Legacy and influence

Branham was the "initiator of the post-World War II healing revival"[28] and, along with Oral Roberts, was one of its most revered leaders.[178][179] Branham is most remembered for his use of the "sign-gifts" that awed the Pentecostal world.[54] According to writer and researcher Patsy Sims, "the power of a Branham service and his stage presence remains a legend unparalleled in the history of the Charismatic movement."[93] The many revivalists who attempted to emulate Branham during the 1950s spawned a generation of prominent Charismatic ministries.[102] Branham has been called the "principal architect of restorationist thought" of the Charismatic movement that emerged out of the healing revival.[1] The Charismatic view that the Christian church should return to a form like that of the early church has its roots in Branham's teachings during the healing revival period.[1] The belief is widely held in the modern Charismatic movement,[1] and the legacy of his restorationist teaching and ministering style is evident throughout televangelism and the Charismatic movement.[180]

The more controversial doctrines Branham espoused in the closing years of his ministry were rejected by the Charismatic movement, which viewed them as "revelatory madness".[lower-alpha 10] Charismatics are apologetic towards Branham's early ministry and embrace his use of the "sign-gifts". Charismatic author John Crowder wrote that his ministry should not be judged by "the small sliver of his later life", but by the fact that he indirectly "lit a fire" that began the modern Charismatic movement.[111] Non-Charismatic Christianity completely rejected Branham.[lower-alpha 11]

Crowder said Branham was a victim of "the adoration of man" because his followers began to idolize him in the later part of his ministry.[183] Harrell took a similar view, attributing Branham's teachings in his later career to his close friends, who manipulated him and took advantage of his lack of theological training.[115] Weaver also attributed Branham's eschatological teachings to the influence of a small group of his closest followers, who encouraged his desire for a unique ministry.[184] According to Weaver, to Branham's dismay,[120] his followers had placed him at the "center of a Pentecostal personality cult" in the final years of his ministry.[185] Edward Babinski describes Branham's followers as "odd in their beliefs, but for the most part honest hard-working citizens", and wrote that calling them a cult "seems unfair".[145] While rejecting Branham's teachings, Duyzer offered a glowing review of Branham's followers, stating he "had never experienced friendship, or love like we did there".[186]

Though Branham is no longer widely known outside Pentecostalism,[185] his legacy continues today.[155] Summarizing the contrasting views held of Branham, Kydd stated, "Some thought he was God. Some thought he was a dupe of the devil. Some thought he was an end-time messenger sent from God, and some still do."[75] Followers of Branham's teachings can be found around the world; Branham claimed to have made over one million converts during his campaign meetings.[187] In 1986, there were an estimated 300,000 followers.[188][lower-alpha 12] In 2000, the William Branham Evangelical Association had missions on every inhabited continent—with 1,600 associated churches in Latin America and growing missions across Africa.[180] In 2018, Voice of God Recordings claimed to serve Branham-related support material to about two million people through the William Branham Evangelical Association.[189]

Notes

- Branham's birthdate has also been reported to be April 6, 1907, and April 8, 1908.[8]

- Pentecostalism is a renewal movement that started in the early 20th century that stresses a post-conversion baptism with the Holy Spirit for all Christians, with speaking in tongues ("glossolalia") as the initial evidence of this baptism.[16]

- Oneness Pentecostalism is a subset of churches within Pentecostalism which adhere to a modalistic view of God. Their baptismal formula is done "in the name of Jesus", rather than the more common Trinitarian formula "in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit".[26]

- The United Nations debate on how to treat European Jewry following the Holocaust began in January 1946, with a committee recommending settling Jews in Palestine in April 1946. Britain announced its intention to divide Palestine in February 1947; the partition plan was adopted by the UN in November 1947, and State of Israel formally became a nation on May 14, 1948.[39]

- Pre-millennial dispensationalism views the establishing of a Jewish state as a sign of the imminent return of Christ.[40]

- Voice of Healing was renamed Christ For the Nations in 1971

- Jones ultimately rejected all of Christianity as "fly away religion", rejected the Bible as being a tool to oppress women and non-whites, and denounced the Christian God as a "Sky God" who was "no God at all". Historian Catherine Wessinger concludes Jones used Christianity as a vehicle to covertly advance his personal ideology [110]

- Weaver records Branham believed it was "the mark of the beast", whereas Harrell records he believed it was "a mark of the beast".

- In December 1964, Branham prophesied that Los Angeles would sink into the Pacific Ocean when struck by the wrath of God; this prophecy was subsequently embellished into a prediction that an area of land 1,500 miles (2,400 km) long, 300–400 miles (480–640 km) wide, and 40 miles (64 km) deep would break loose, causing waves that would "shoot plumb out to Kentucky".[167]

- Charismatic writer Michael Moriarty stated, "Branham's aberrational teachings not only cultivated cultic fringe movements like the Latter Rain Movement and the Manifested Sons of God, but they also paved a pathway leading to false predictions, revelatory madness, doctrinal heresies, and a cultic following that treated his sermons as oral scriptures".[181]

- Hanegraaff in Counterfeit Revival condemned the entire evangelical movement as a cult and singled out Branham, saying his "failed prophecies were exceeded only by his false doctrine" in infamy.[182]

- Weaver based his estimate on numbers reported by Branham's son. The estimate included 50,000 in the United States, with a considerable following in Central and South America (including 40,000 in Brazil), India, and Africa; particularly in Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[188]

Footnotes

- Weaver 2000, p. v.

- Moriarty 1992, p. 119.

- Moriarty 1992, p. 55.

- Harrell 1978, p. 28.

- Weaver 2000, p. 22.

- Crowder 2006, p. 323.

- Duyzer 2014, pp. 26–27.

- Duyzer 2014, p. 25.

- Weaver 2000, p. 23.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 23–24.

- Duyzer 2014, p. 27.

- Weaver 2000, p. 25.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 26, 33.

- Weaver 2000, p. 33.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 32–34.

- See Grenz, p. 90.

- Staff writers (June 2, 1933). "Fourteen Converted". Jeffersonville Evening News. Jeffersonville, Indiana. p. 4.

- Harrell 1978, p. 29.

- Weaver 2000, p. 27.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 27–28.

- Weaver 2000, p. 28.

- Weaver 2000, p. 29.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 28–29.

- Weaver 2000, p. 32.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 37–38.

- See Johns, p. 154.

- Weaver 2000, pp. v–vii.

- Harrell 1978, p. 25.

- Crowder 2006, p. 321.

- Hanegraaff 2001, p. 173.

- Harrell 1978, pp. 11–12.

- Harrell 1978, pp. 4–6, 11.

- Crowder 2006, p. 324.

- Anderson 2004, p. 58.

- Weaver 2000, p. 47.

- Krapohl & Lippy 1999, p. 69.

- Kydd 1998, p. 177.

- Weaver 2000, p. 37.

- "Milestones: 1945–1952 – Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- Weaver 2000, p. 37.

- Weaver 2000, p. 45.

- Weaver 2000, p. 46.

- Sims 1996, p. 193.

- Sims 1996, p. 76.

- Harrell 1978, p. 31.

- Harrell 1978, p. 32.

- Harrell 1978, p. 47.

- Moriarty 1992, p. 47.

- Harrell 1978, pp. 31–32.

- Faupel, D. William (2010). "The New Order of the Latter Rain: Restoration or Renewal?". In Wilkinson, Michael; Althouse, Peter (eds.). Winds from the North: Canadian Contributions to the Pentecostal Movement. Brill. pp. 240–241, 247. ISBN 978-90-04-18574-6.

- Harrell 1978, p. 33.

- Crowder 2006, p. 326.

- Harrell 1978, p. 39.

- Harrell 1978, p. 36.

- Harrell 1978, p. 6.

- Harrell 1978, p. 11.

- Moriarty 1992, p. 49.

- Weaver 2000, p. 49.

- Harrell 1978, p. 34.

- Harrell 1978, p. 38.

- Kydd 1998, p. 173.

- Weaver 2000, p. 51.

- Weaver 2000, p. 68.

- Weaver 2000, p. 70.

- Harrell 1978, p. 37.

- Moriarty 1992, p. 51.

- Moriarty 1992, p. 50.

- Moriarty 1992, p. 40.

- Kydd 1998, p. 172.

- Kydd 1998, p. 178.

- Harrell 1978, p. 180.

- Harrell 1978, p. 35.

- Kydd 1998, pp. 172–173.

- Kydd 1998, p. 179.

- Kydd 1998, p. 180.

- Kydd 1998, p. 175.

- Weaver 2000, p. 72.

- Weaver 2000, p. 71.

- Weaver 2000, p. 50.

- Weaver 2000, p. 74.

- Weaver 2000, p. 57.

- "Upshaw, William D". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Crowder 2006, p. 327.

- "Miracle sets boy walking normally". Durban Sunday Tribune. Durban, South Africa. November 11, 1951. p. 15. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- "Cripples rise from wheelchairs and walk". The Natal Mercury. Durban, South Africa. November 23, 1951. p. 12. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- "Minister cured deafness, says 18-year-old girl". Winnipeg Free Press. Manitoba, Canada. July 15, 1947. p. 1. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- "300 fill out cards at healer service". El Paso Herald Post. El Paso, Texas. December 17, 1947. p. 7. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- "Claims service benefitted boy". Logansport Press. Logansport, Indiana. June 12, 1951. p. 10. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- Hollenweger 1972, p. 354.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 50–51.

- Forsberg, David (March 18, 2018). "Listens to a dead "kvaksalver" everyday". Norway: NRK. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- Weaver 2000, p. 56.

- Sims 1996, p. 195.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 51–52.

- Weaver 2000, p. 93.

- Harrell 1978, pp. 39–40.

- Harrell 1978, p. 102.

- "Ephemera of William Branham". www.wheaton.edu. Billy Graham Center, Wheaton College. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- Crowder 2006, p. 328.

- Harrell 1978, p. 49.

- Weaver 2000, p. 94.

- Harrell 1978, p. 40.

- Weaver 2000, p. 91.

- Harrell 1978, p. 160.

- Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 50–52.

- Wessinger, pp. 217–220.

- Collins, John; Duyzer, Peter M. (October 20, 2014). "The Intersection of William Branham and Jim Jones". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. San Diego State University. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- Collins, John (October 7, 2016). "Colonia Dignidad and Jonestown". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. San Diego State University. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- Collins, John; Duyzer, Peter (October 7, 2016). "Deep Study: Reverend Jim Jones of Jonestown". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. San Diego State University. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Wessinger, pp. 217–220.

- Crowder 2006, p. 330.

- Weaver 2000, p. 92.

- Grenz, p. 162.

- Harrell 1978, p. 173.

- Harrell 1978, p. 163.

- Weaver 2000, p. 108.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 108–109.

- Weaver 2000, p. 97.

- Weaver 2000, p. 140.

- Weaver 2000, p. 103.

- Weaver 2000, p. 104.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 118, 98.

- Weaver 2000, p. 118.

- Kydd 1998, p. 176.

- Weaver 2000, p. 98.

- Harrell 1978, p. 164.

- Kydd 1998, pp. 173–174.

- Weaver 2000, p. 121.

- Weaver 2000, p. 86.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 117–118.

- Douglas Gordon Jacobsen. (2006) A Reader in Pentecostal Theology: Voices from the First Generation, Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253218624 p. 31.

- Weaver 2000, p. 117.

- Weaver 2000, p. 119.

- Weaver 2000, p. 120.

- Weaver 2000, p. 122.

- Weaver 2000, p. 114.

- Niebuhr 1975, p. 45.

- Weaver 2000, p. 17, 41.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 109, 111.

- Weaver 2000, p. 111.

- Weaver 2000, p. 109.

- Kydd 1998, p. 169.

- Weaver 2000, p. 110.

- Weaver 2000, p. 112.

- Babinski 1995, p. 277.

- Weaver 2000, p. 113.

- Weaver 2000, p. 125.

- Kydd 1998, p. 174.

- Weaver 2000, p. 124.

- Weaver 2000, p. 123.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 99, 103.

- Weaver 2000, p. 99.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 129–130.

- Weaver 2000, p. 129.

- Larson 2004, p. 79.

- Moriarty 1992, pp. 49–50.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 99, 128.

- Weaver 2000, p. 128.

- Weaver 2000, p. 133.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 99–100.

- Weaver 2000, p. 101.

- Weaver 2000, p. 115.

- Weaver 2000, p. 116.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 116–117.

- Duyzer 2014, pp. 61–83.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 30–31.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 103–104.

- Weaver 2000, pp. v–vi.

- Moriarty 1992, p. 53.

- Moriarty 1992, p. 56.

- Moriarty 1992, p. 54.

- "Head-on Collision Kills 1, Injures 6". Friona Star. Friona, Texas. December 23, 1965. p. 3. hdl:10605/243339.

- Weaver 2000, p. 105.

- Liardon 2003, p. 354.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 153–154.

- Weaver 2000, p. 154.

- Weaver 2000, p. 155.

- Harrell 1978, p. 19.

- Weaver 2000, p. 58.

- Weaver 2000, p. vi.

- Moriarty 1992, p. 55.

- Hanegraaf 2001, p. 152.

- Crowder 2006, p. 331.

- Weaver 2000, p. 102.

- Weaver 2000, p. x.

- Duyzer 2014, p. 1.

- Kydd 1998, p. 168.

- Weaver 2000, pp. 151–153.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Voice of God Recordings. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

References

- Anderson, Allan (2004). An Introduction to Pentecostalism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53280-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Babinski, Edward T. (1995). Leaving the Fold: Testimonies of Former Fundamentalists. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1615921676.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crowder, John (2006). Miracle Workers, Reformers, and The New Mystics. Destiny Image. ISBN 978-0-7684-2350-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duyzer, Peter M. (2014). Legend of the Fall, An Evaluation of William Branham and His Message. Independent Scholar's Press. ISBN 978-1-927581-15-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grenz, Stanley; Guretzki, David; Nordling, Cherith Fee (1999). Pocket Dictionary of Theological Terms. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-830-81449-7.

- Hanegraaff, Hank (2001). Counterfeit Revival. Thomas Nelson Publishers. ISBN 0-8499-4294-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harrell, David (1978). All Things Are Possible: The Healing and Charismatic Revivals in Modern America. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-525-24136-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hollenweger, Walter J. (1972). Pentecostalism: Origins and Developments Worldwide. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-4660-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Krapohl, Robert; Lippy, Charles (1999). The Evangelicals: A Historical, Thematic, and Biographical Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30103-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kydd, Ronald A. N. (1998). Healing through the Centuries: Models for Understanding. Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-913573-60-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Larson, Bob (2004). Larson's Book of World Religions and Alternative Spirituality. Tyndale House Publishers. Inc. ISBN 0-8423-6417-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Liardon, Roberts (2003). God's Generals: Why They Succeeded And Why Some Fail. Whitaker House. ISBN 978-0-88368-944-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moriarty, Michael (1992). The New Charismatics. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-53431-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Niebuhr, H. Richard (1975). Christ and Culture. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-061-30003-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reiterman, Tom; Jacobs, John (1982). Raven: The Untold Story of Rev. Jim Jones and His People. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-24136-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sims, Patsy (1996). Can Somebody Shout Amen!: Inside the Tents and Tabernacles of American Revivalists. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813108865.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wessinger, Catherine (2000). How the Millennium Comes Violently: From Jonestown to Heaven's Gate. Seven Bridges Press. ISBN 978-1-889119-24-3.

- Weaver, C. Douglas (2000). The Healer-Prophet: William Marrion Branham (A study of the Prophetic in American Pentecostalism). Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-865-54710-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Burgess, Stanley M.; van der Maas, Eduard M. (2002). The New International Dictionary of Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-22481-5.

- Hollenweger, Walter J. (1972). The Pentecostals. University of Virginia. ISBN 978-0-9435-7502-5.

- Hyatt, Eddie L. (2002). 2000 Years of Charismatic Christianity. Charisma House. ISBN 978-0-88419-872-7.

- Johns, Jackie David (2005). Fahlbusch, Erwin; et al. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802824134.

- Sheryl, J. Greg (2013). "The Legend of William Branham" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal. Personal Freedom Outreach. 33 (3). ISSN 1083-6853.

- Reid, Daniel G. (1990). Dictionary of Christianity In America. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1776-4.

- Robins, R. G. (2010). Pentecostalism in America. Praeger (ABC-CLIO, LLC). ISBN 978-0-313-35294-2.

- Stewart, Don (1999). Only Believe: An Eyewitness Account of the Great Healing Revival of the 20th Century. Treasure House. ISBN 978-1-56043-340-8.

- Weremchuk, Roy (2019). Thus Saith the Lord? William M. Branham (1909–1965). Leben und Lehre. Deutscher Wissenschafts-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86888-150-9.

Hagiographical

- Green, Pearry (2011). The Acts of the Prophet. Tucson Tabernacle. OCLC 827238316.

- Lindsay, James Gordon (1950). William Branham: A Man Sent From God (PDF). William Branham Evangelistic Association. ASIN B0007ENQ64.

- Stadsklev, Julius (1952). William Branham: A Prophet Visits South Africa. Julius Stadsklev. ASIN B0007EW174. OCLC 1017376491.

- Vayle, Lee (1965). Twentieth Century Prophet. William Branham Evangelistic Association.

External links

- "William Branham Evangelistic Association". Voice of God Recordings. Retrieved February 28, 2018.