William Garrow Lettsom

William Garrow Lettsom FRAS (1805–14 Dec 1887) was a British diplomat, mineralogist and spectroscopist. He was instrumental in procuring the publication of the secret Treaty of the Triple Alliance between Argentina, the Empire of Brazil and Uruguay.

Early life

Lettsom was born into a Quaker family at Fulham in March 1805. His paternal grandfather John Coakley Lettsom was a famous physician, philanthropist and abolitionist who held that sea-bathing[1] was good for public health.

His maternal grandfather − with whom he lived in his youth − was Sir William Garrow the celebrated criminal defender, afterwards a judge, who introduced the phrase "presumed innocent until proven guilty" into the common law and whose life inspired the television drama series Garrow's Law.

Lettsom was educated at Westminster School and Cambridge University.[2]

Literary acquaintance

As an undergraduate at Cambridge University Lettsom befriended the author William Makepeace Thackeray and was the (or an) editor of The Snob in which some of Thackeray's earliest work appeared;[3] Lettsom has been identified as the character Tapeworm[4] in Thackeray's novel Vanity Fair.[5] Lettsom was well acquainted with the cartoonist George Cruikshank, illustrator of the early works of Charles Dickens. Lettsom was a contributor to various literary periodicals under the pseudonym Dr. Bulgardo.[2]

Scientist

Lettsom was a competent scientist in an age where it was still possible for an amateur to be so. He was best known as the joint author of Greg and Lettsom's Manual of the Mineralogy of Great Britain and Ireland,[6] which was the most complete and accurate work that had appeared on the mineralogy of the British Isles. But his scientific interests were wider, and he corresponded with the most eminent workers in spectroscopy. He was a member of the London Electrical Society and the author of several papers on geological, electrical and spectroscopic subjects.[7]

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1849. In that year he communicated an experiment in bioelectricity: by making a wound in a finger and inserting the electrode of a galvanometer, while placing the other electrode in contact with an unwounded finger, a current was observed to flow. Lettsom observed that the experiment was repeatable for he had tried it himself.[8] In 1857 while on diplomatic service in Mexico he sent to the Royal Entomological Society of London some seeds which, when put in a warm place, became "very lively". The grub responsible had not been investigated scientifically before, wrote Lettsom, and he asked the Society to do so. These were the celebrated Mexican jumping beans.[9]

During his appointment as Consul-General and Chargé d'Affaires to the Republic of Uruguay, he carried a 9 inches Henry Fitz telescope for astronomical observation at the southern hemisphere. Due to unknown problems, he sent the telescope back to New York to be checked and adjusted by the telescope maker. The telescope was received by Lewis Rutherford, pioneer astrophotographer and spectroscopist also associated of the Royal Astronomical Society, who helped Henry Fitz on this tasks. The telescope was left in Uruguay and is in use until today by the Amateur Astronomer Association.

Diplomat

After being called to the Bar by Lincoln's Inn he entered the diplomatic service. After postings in Berlin, Munich (1831), Washington (1840), Turin (1849) and Madrid (1850) he was appointed secretary to the Legation at Mexico (1854) and became the Chargé d'affaires.

In the unreformed British diplomatic service there were no examinations; candidates were appointed by the influence of political friends. This caused criticism. In the House of Commons on 22 May 1855 the motion was

That it is the opinion of this House that the complete Revision of our Diplomatic Establishment recommended in the Report of the Select Committee of 1850 on Official Salaries should be carried into effect.

In this debate Lettsom was used as a case in point to illustrate the defects of the unreformed system. It has been noted that Lettsom, "who had invariably conducted himself to the satisfaction of those who employed him",[10] received one of the slowest promotions in the diplomatic service.[11] A diplomat was expected to be a gentleman and to have a private income whereby he could receive unpaid diplomatic appointments. Hence nine of the twenty-three years of Lettsom's service were unsalaried; promotion was slow. This glacial treatment did not apply, however, to those who had powerful political friends, for they were soon appointed to agreeable capitals at enormous salaries. [10] The motion was carried by 112 votes to 57, [12] Mr Otway MP remarking that "The person who had shown himself to be the fittest man, whether he was the son of a Peer or a tailor, should be chosen".[13]

While in Mexico the British government suspended relations with that country on Lettsom's representation, and he was the object of an attempted assassination. Between 1859 and 1869 Lettsom was appointed Consul-General and Chargé d'Affaires to the Republic of Uruguay.[2]

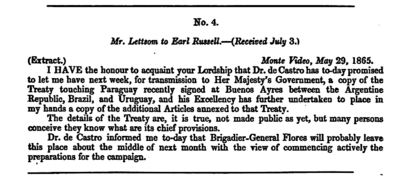

Treaty of the Triple Alliance

In 1864 and early 1865 Paraguayan forces under the orders of Francisco Solano López seized Brazilian and Argentine shipping and invaded the provinces of the Mato Grosso and Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) and Corrientes (Argentina). On 1 May 1865 Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay signed the Treaty of the Triple Alliance against Paraguay. By Article XVIII of the Treaty its provisions were to be kept secret until its "principal object"[14] should be obtained. One of its provisions concerned the acquisition by Argentina of large tracts of territory then in dispute between it and Paraguay. Lettsom was not satisfied about this and surreptitiously obtained a copy of the Treaty from the Uruguayan diplomat Dr Carlos de Castro. He forwarded it to London and the British government ordered it to be translated into English and published to Parliament. When the text became available in South America there was outrage in several quarters, some because of the Treaty's content, others because it had been published at all.[15]

Lettsom retired from the diplomatic service in 1869. He never married.[16] He died of acute bronchitis on 14 December 1887.[17]

Notes

- Urban, p. 143.

- Obituary, p. 165.

- Benét, p. 62.

- Presumably because his grandfather Dr Lettsom produced a cure for tapeworm (by dosing the patients with paraffin).

- Greig, pp. 102–3.

- Greg and Lettsom.

- Obituary, pp. 165–6.

- Vanable, p. 164.

- Entomological Transactions, p. 90.

- Hansard, p. 917.

- Bindoff, p. 162.

- Hansard, pp. 898–921.

- Hansard, p. 919.

- The deposition of López or (on another view) the demolition of the Fortress of Humaitá.

- Whigham 2015, locations 1169–1172.

- Hostettler and Braby, p. 177.

- Royal Astronomical Society, p. 167.

References

- Benét, Laura (1947). Thackeray, of the Great Heart and Humorous Pen. Dodd Mead.

- Bindoff, S.T. (1935). "The Unreformed Diplomatic Service, 1812–60". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Cambridge University Press. 18: 143–172. doi:10.2307/3678607.

- Greg, Robert Philips; Lettsom, William G (1858). Manual of the Mineralogy of Great Britain and Ireland. London: John Van Voorst.

- Greig, John Young Thomson (1950). Thackeray: A reconsideration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hansard's Parliamentary Debates Third Series 18 & 19 Victoriae 1855. 138. London: Cornelius Buck. 1855.

- Hofstetter, John; Braby, Richard (2010). Sir William Garrow: His Life, Times and Fight for Justice. Sherfield on Loddon, Hampshire: Waterside Press. ISBN 9781904380 559.

- "Obituary: List of Fellows and Associates deceased Lettsom, W.G." (PDF). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 68: 165. February 1888. Bibcode:1888MNRAS..48R.165.

- Proceedings of the Entomological Society of London 1856. London: Entomological Society of London.

- Urban, Sylvanus (1817). The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Quarterly. 87. London: Nichols Son & Bentley.

- Vanable, Joseph W, Jr (2007). "A History of bioelectricity in development and regeneration". In Dinsmore, Charles E. (ed.). A History of Regeneration Research. Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–178. ISBN 9780521047968.

- Whigham, Thomas (2015). La Guerra de la Triple Alianza Volumen II: El triunfo de la violencia, el fracaso de la paz (in Spanish). Kindle. (Conflicting ASIN data furnished by Amazon website.)