White bread

White bread typically refers to breads made from wheat flour from which the bran and the germ layers have been removed (and set aside) from the whole wheatberry as part of the flour grinding or milling process, producing a light-colored flour.[2] This milling process can give white flour a longer shelf life by removing the natural oils from the whole grain. Removing the oil allows products made with the flour, like white bread, to be stored for longer periods of time avoiding potential rancidity.

| |

| Type | Bread |

|---|---|

| Main ingredients | Wheat flour |

| Other information | glycaemic load 37 (100g)[1] |

The flour used in white breads are bleached further—by the use of chemicals such as potassium bromate, azodicarbonamide, or chlorine dioxide gas to remove any slight, natural yellow shade and make its baking properties more predictable. This is banned in the EU. Some flour bleaching agents are also banned from use in other countries.

In the United States, consumers sometimes refer to white bread as sandwich bread and sandwich loaf.[3]

White bread contains 1/2 of the magnesium found in whole-wheat bread.

History

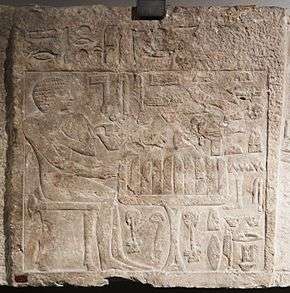

Bread made with grass grains goes back to the pre-agriculture Natufi proto-civilization 12,000 years ago.[4] But only wheat can feasibly be sifted to produce pure white starch, a technique that goes back to at least ancient Egypt.[5] Because wheat was the most expensive grain to grow, and the process to sift it labor-intensive, white flour was generally limited to special occasions and the wealthy, until the mid 19th century. Then industrial processes eliminated the labor cost, allowing prices to fall until it was accessible to the middle class.[6]

In the US, corn meal was the standard grain for bread until closing in on the 20th century, while in Europe it was other grains.

But once accessible, white bread became very popular in industrialized countries for a number of reasons:

- That it was traditionally for the wealthy made white wheat bread seem desirable.

- It also was easier to see as pure and clean, at a time when some foods could be poorly made and adulterated.

- And the lack of both coarseness and complex flavor profile made it a popular medium for the delivery of flavorful condiments.

- It is more easily chewed and digested. This provides more of the most important macro nutrient, calories. It also does make some micronutrients more digestible, some studies finding that the added nutrition in whole grains tends to pass through the body unabsorbed.[7]. For some body types and diets, white flour may have been a nutritional benefit.[8]

- Once it could be easily produced, it went from the most expensive to among the cheapest kinds of flour

- It can last longer. The wheat oil in whole grain breads can go rancid over time, spoiling its flavor.

But there was a backlash, almost immediately, from this reversal in white flour popularity. The healthism movement considered this strange new trend a threat, helping give rise to whole grain alternatives popular to this day, like graham crackers and corn flakes, which indeed have (in their original whole grain form) more fiber and a few extra micronutrients. Some racists claimed that white bread was, ironically, bad for white people, weakening their strength.[9]

But eventually, the revolution of white bread from elite to common popularity became symbolic of the success of industrialization and capitalism in general, especially paired with the advent of common machine bread slicing in the 1920s.

White bread has remained the most popular type of bread in the US and much of the industrialized world, despite a generational cycle of backlash against it.

White bread fortification

While a bran and wheat germ discarding milling process can help improve white flour's shelf life, it does remove nutrients like some dietary fiber, iron, B vitamins, micronutrients[10] and essential fatty acids. Since 1941, however, fortification of white flour-based foods with some of the nutrients lost in milling, like thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, and iron was mandated by the US government in response to the vast nutrient deficiencies seen in US military recruits at the start of World War II.[11] This fortification led to nearly universal eradication of deficiency diseases in the US, such as pellagra and beriberi (deficiencies of niacin and thiamine, respectively) and white bread continues to contain these added vitamins to this day.[12]

Folic acid is another nutrient that some governments have mandated is added to enriched grains like white bread. In the US and Canada, these grains have been fortified with mandatory levels of folic acid since 1998 because of its important role in preventing birth defects. Since fortification began, the rate of neural tube defects has decreased by approximately one-third in the US.[13][14][15]

See also

- Brown bread, a bread that was considered undesirable in early-19th-century Europe

- Chorleywood bread process, another common process for mass-produced bread

- Flour treatment agent

- Graham bread, an early reintroduction of an unbleached bread

- Maida flour, a bleached flour typically used to make a white bread in India

- Plain loaf

- Pullman loaf, bread baked in a lidded pan, responsible for square-shaped slices

- Rye bread, a bread that can be darker or neutral in color

- Sliced bread, pre-sliced and packaged bread, first sold in 1928

- Vienna bread, baking processes that lead to lighter, less sour breads

- Whole wheat bread, one common alternative to white bread

External links

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to White bread. |

- NPCS board (2012-10-01). Manufacture of Food & Beverages (2nd Edn.). Niir Project Consultancy Services, 2012. ISBN 9789381039113.

- Mercuri, B. (2009). American Sandwich. Gibbs Smith, Publisher. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4236-1192-9.

- Archaeobotanical evidence reveals the origins of bread 14,400 years ago in northeastern Jordan

- THE HISTORY OF WHITE FLOUR

- Why did our ancestors prefer white bread to wholegrains?

- Whole Wheat Is No Healthier than White Bread, Food Scientists Claim

- White Bread May Not Be Bad for You After All

- American History Baked Into The Loaves Of White Bread

- "Grains - What foods are in the grain group?". ChooseMyPlate.gov. USDA.gov. 2009-10-01. Retrieved 2012-01-06.

- American Dietetic Association (2005). "Position of the American Dietetic Association: Fortification and Nutritional Supplements". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 105 (8): 1300–1311. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.06.009. PMID 16182650.

- "Southern Medical Journal". Journals.lww.com. 2010-09-30. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- Williams, L.J., et al. Decline in the prevalence of spina bifida and anencephaly by race/ethnicity: 1995-2002. Pediatrics. 2005; 116: 580-586.

- "Cambridge Journals Online - Public Health Nutrition". Journals.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- Grosse, S., et al. Reevaluating the benefits of folic acid fortification in the United States: economic analysis, regulation, and public health. Am J Public Health. 2005; 95: 1917-1922.

| Look up white bread in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |