Western gull

The western gull (Larus occidentalis) is a large white-headed gull that lives on the west coast of North America. It was previously considered conspecific with the yellow-footed gull (Larus livens) of the Gulf of California. The western gull ranges from British Columbia, Canada to Baja California, Mexico.[2]

| Western gull | |

|---|---|

%2C_Point_Lobos%2C_CA%2C_US_-_May_2013.jpg) | |

| Adult | |

| |

| 1st winter juvenile | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Larus |

| Species: | L. occidentalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Larus occidentalis (Audubon, 1839) | |

| |

Description

.jpg)

The western gull is a large gull that can measure 55 to 68 cm (22 to 27 in) in total length, spans 130 to 144 cm (51 to 57 in) across the wings, and weighs 800 to 1,400 g (1.8 to 3.1 lb).[3][4] The average mass among a survey of 48 gulls of the species was 1,011 g (2.229 lb).[5] Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 38 to 44.8 cm (15.0 to 17.6 in), the bill is 4.7 to 6.2 cm (1.9 to 2.4 in) and the tarsus is 5.8 to 7.5 cm (2.3 to 3.0 in).[3] The western gull has a white head and body, and gray wings. It has a yellow bill with a red subterminal spot (this is the small spot near the end of the bill that chicks peck in order to stimulate feeding). It closely resembles the slaty-backed gull (Larus schistisagus). In the north of its range it forms a hybrid zone with its close relative the glaucous-winged gull (Larus glaucescens). Western gulls take approximately four years to reach their full plumage,[6] their layer of feathers and the patterns and colors on the feathers. The western gull typically lives about 15 years, but can live up to 25 years. The largest western gull colony is on the Farallon Islands, located about 26 mi (40 km) west of San Francisco, California;[7] an estimated 30,000 gulls live in the San Francisco Bay area. Western gulls also live in the Oregon Coast.[8]

Distribution and habitat

The western gull is a year-round resident in California, Oregon, Baja California, and southern Washington. It is migratory, moving to northern Washington, British Columbia, and Baja California Sur to spend the nonbreeding season.

Behavior

The western gull rarely ventures more than approximately 100 miles inland, almost never very far from the ocean;[6] it is almost an exclusively marine gull. It nests on offshore islands and rocks along the coast, and on islands inside estuaries. A colony also exists on Ano Nuevo Island, then Anacapa Island in Channel Islands National Park, and Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. In the colonies, long term pairs aggressively defend territories whose borders may shift slightly from year to year, but are maintained for the life of the male.

Feeding

Western gulls feed in pelagic environments and in intertidal environments. At sea, they take fish[7] and invertebrates like krill, squid and jellyfish. They are unable to dive and feed exclusively on the surface of the water. On land they feed on seal and sea lion carcasses and roadkill, as well as cockles, starfish, limpets and snails in the intertidal zone. They also feed on human food refuse, in human-altered habitats including landfills, and take food given to them, or stolen from people at marinas, beaches and parks. Western gulls are known to be predatory, killing and eating the young of other birds, especially ducklings, and even the adults of some smaller bird species. Western gulls, including one who lived at Oakland's Lake Merritt are known for killing and eating pigeons (rock doves). They will also snatch fish from a cormorant's or pelican's mouth before it is swallowed.

Reproduction

A nest of vegetation is constructed inside the parent's territory and 3 eggs are laid. These eggs are incubated for a month. The chicks, once hatched, remain inside the territory until they have fledged. Chicks straying into the territory of another gull are liable to be killed by that territory's pair. Chick mortality is high, with on average one chick surviving to fledging. On occasion, abandoned chicks will be adopted by other gulls.

Hybridization

In Washington state, the western gull hybridizes frequently with the glaucous-winged gull, and may closely resemble a Thayer's gull.[6] The hybrids have a flatter and larger head and a thicker bill with a pronounced angle on the lower part of the bill, which distinguishes it from the smaller Thayer's gull.[6]

Western gulls and humans

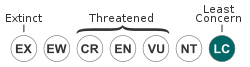

The western gull is currently not considered threatened. However, they have, for a gull, a restricted range. Numbers were greatly reduced in the 19th century by the taking of seabird eggs for the growing city of San Francisco. Western gull colonies also suffered from disturbance where they were turned into lighthouse stations, or, in the case of Alcatraz, a prison.

Western gulls are very aggressive when defending their territories and consequently were persecuted by some as a menace. The automation of lighthouses and the closing of Alcatraz Prison allowed the species to reclaim parts of its range. They are currently vulnerable to climatic events like El Niño events and oil spills.

Western gulls have become a serious nuisance to the San Francisco Giants baseball team. Thousands of gulls fly over AT&T Park in San Francisco during late innings of games. They swarm the field, defecate on fans, and after games eat leftovers of stadium food in the seats; how the birds know when games are about to end is unknown. The gulls left while a red-tailed hawk visited the park in late 2011, but returned after the hawk disappeared. Federal law prohibits shooting the birds, and hiring a falconer would cost the Giants $8000 a game.[8]

In media

The western gull was one of the antagonists in Alfred Hitchcock's famous movie The Birds which was filmed in Bodega Bay, California.

Gallery

A western gull chick on Alcatraz Island

A western gull chick on Alcatraz Island 3-week-old chick

3-week-old chick Portrait

Portrait Feeding on a starfish

Feeding on a starfish Vocalizing

Vocalizing Adults fighting

Adults fighting A pair at Point Lobos

A pair at Point Lobos

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Larus occidentalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Western Gull". U.S. National Audubon Society. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- Olsen, Klaus Malling; Larsson, Hans (2004). Gulls of North America, Europe, and Asia. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691119977.

- Harrison, Peter (1991). Seabirds: An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-395-60291-1.

- Dunning Jr., John B., ed. (1992). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- "Western Gull". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- Emslie, Steven D.; Messenger, Sharon L. (March 1991). "Pellet and Bone Accumulation at a Colony of Western Gulls". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 11 (1): 133–136. doi:10.1080/02724634.1991.10011380. JSTOR 4523362.

- Rogers, Paul (20 July 2013). "AT&T Park gulls vex San Francisco Giants". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

Additional sources

- Pierotti, R.J.; Annett, C.A. (1995). Poole, A.; Gill, F. (eds.). Western Gull (Larus occidentalis). The Birds of North America. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Larus occidentalis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Larus occidentalis |

- Western Gull Facts - from University of Washington Nature Mapping Program

- Oregon Coast Today - Seagull article

- "Western gull media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Western gull photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Western gull at IUCN Red List maps