Violence against women in Pakistan

Violence against women, particularly intimate partner violence and sexual violence, is a major public health problem and a violation of women's human rights in Pakistan.[1] Violence against women in Pakistan is part of an issue that faces the entire region the country is situated in.[2] Women in Pakistan mainly encounter violence by being forced into marriage, through workplace sexual harassment, domestic violence and by honour killings.[2]

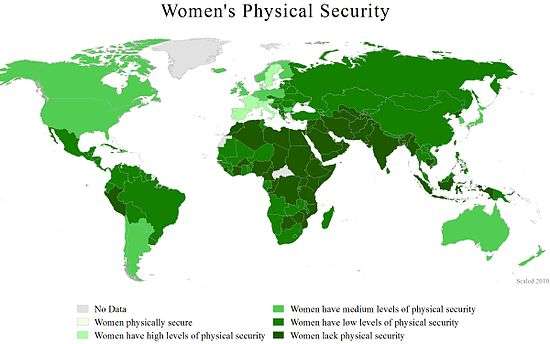

A survey carried out by the Thomson Reuters Foundation ranked Pakistan as the sixth most dangerous country in the world for women.[3]

History

According to Dr. Rukhsana Iftikhar and Dr. Maqbool Ahmad Awan in the Journal of Political Studies, "Pakistan is an agrarian state where the concept of personal ownership is very much common", with the two writing "Women are also considered personal properties in Pakistan".[2] The two state that such violence persists due to religious and cultural norms within the country.[2] Pakistani women are expected to maintain modesty while men are expected to project masculinity to keep honour among their families.[4] Traditional views in Pakistan believe that if dishonour is not corrected, it may spread beyond singular incident and into the community.[4]

Acts of violence

Domestic violence

In a 2008 survey, 70% of women respondents reported that they experienced domestic violence.[2] According to a 2009 Human Rights Watch report, 70-90% of Pakistani women suffered with some kind of domestic violence.[5] About 5,000 women are killed annually from domestic violence in Pakistan, with thousands of other women maimed or disabled.[6] Law enforcement authorities do not view domestic violence as a crime and usually refuse to register any cases brought to them.[7]

In the 2012-2013 Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey, 3,867 married or previously married women were questioned.[8] Of the respondents, 47% of these women believed that physical violence was just if a wife had argued with her husband.[8] The survey found that such beliefs on domestic violence were often passed down to future generations of children.[8]

Marital rape is also a common form of spousal abuse as it is not considered to be a crime under the Zina laws.[9] A study by the United Nations found that 50% of married Pakistani women have experienced sexual violence and 90% have been psychologically abused.[10]

Forced conversion of minority girls

In Pakistan, Hindu and Christian girls are kidnapped, raped, forcibly converted to Islam and forced to marry Muslim men. About 1,000 non-muslim girls are forcibly converted to Islam in Pakistan every year.[11][12] However according to "[t]he All Pakistan Hindu Panchayat (APHP)...[the] majority of cases of marriages between Hindu women and Muslim men were result of love affairs. It said due to honour, the family members of women concoct stories of abduction and forced conversions".[13]

Honour killing

Historically, honour killings have occurred in Pakistan for thousands of years[4] and authorities in the country, legally obligated to treat such incidents as a crime of homicide, often ignore such killings.[14] As of 2019, thousands of honour killings occurred annually in Pakistan.[2]

Rape and sexual violence

The topic of sex is a taboo subject in Pakistan, therefore women often refrain from reporting their experiences with rape.[9] According to a study carried out by Human Rights Watch there is a rape once every two hours[5] and a gang rape every hour.[15][16]

Women's Studies professor Shahla Haeri stated that rape in Pakistan is "often institutionalized and has the tacit and at times the explicit approval of the state".[17][18] According to lawyer Asma Jahangir, who was a co-founder of the women's rights group Women's Action Forum, up to seventy-two percent of women in custody in Pakistan are physically or sexually abused.[19]

Law

The majority of women who are victims of violence have no legal recourse within Pakistan.[7]

Existing laws

Article 25 of the 1973 Pakistani constitution states: "All citizens are equal before law and are entitled to equal protection of law. There shall be no discrimination on the basis of sex. Nothing in this Article shall prevent the State from making any special provision for the protection of women and children.[20]"

Article 23 of the 1973 Constitution states: "Provision as to property. Every citizen shall have the right to acquire, hold and dispose of property in any part of Pakistan, subject to the Constitution and any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the public interest."[21]

Article 310A states: “Punishment for giving a female in marriage or otherwise in badla-e-sulh, wanni or swara.- Whoever gives a female in marriage or otherwise compels her to enter into marriage, as badal-e-sulh, wanni, or swara or any other custom or practice under any name, in consideration of settling a civil dispute or a criminal liability, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to seven years but shall not be less than three years and shall also be liable to fine of five hundred thousand rupees.”[22]

The Prevention of Anti Women Practices Act 2011 states: "Whoever by deceitful or, illegal means deprives any woman from inheriting any movable or immovable property at the time of opening of succession shall be punished with imprisonment for either description for a term which may extend to ten years but not be less than five years or with a fine of one million rupees or both."[23]

List of government departments and NGOs working for women

Legal hotlines provide emergency support and referral services over the phone those in volatile relationships. Hotlines are generally dedicated to women escaping abusive relationships and provide referral to women's shelters. There are various helplines providing services to women in sufferings in Pakistan.

Ministry of Human Rights Women Centre and helplines

The Ministry of Human Rights is managing and operating Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Human Rights Centre for Women in Islamabad. Victims of violence can share their sufferings in strict confidentiality with volunteers and social of pain and humiliation. The Centers is equipped with facilities including free medical, legal, and Shelter Home.

Address: Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Human Rights Centre for Women, Sector H-8/1, St # 04, Pitrass Bukhari Road, Near City School, Ministry of Human Rights, Islamabad. Contact: Manager Numbers:- 051-9101256, 9101257, 9101258[24]

Moreover, a helpline — 1099 — has been launched by the ministry to provide free legal advice on the matter.[21]

PCSW helpline

The Punjab Women's Toll-Free Helpline 1043 and online complaint form is available 24/7. Managed and supervised by PCSW, this helpline team comprises all-women call agents, three legal advisors, phycho social counselor, supervisors and management staff to address inquiries and complaints, and to provide psycho social counseling, on workplace harassment, gender discrimination, property disputes and inheritance rights, domestic violence and other women's issues.[25]

AGHS Legal Aid Cell

AGHS provides legal aid in the violation of human rights by the state or non- state actors, women in obtaining their rights under family law and to women and children, and other victims of the abuse of due process and in prisons to women and juveniles. Email us: aghs@brain.net.pk | Call: 042-35842256-7[26]

SLACC Helpline

Any person across the Pakistan can call the Sindh Legal Advisory Call Centre (SLACC) free of cost on toll free no. 0800-70806 for seeking legal advice on civil, criminal, public service related matters.[27]

DRF Helpline

Digital Rights Foundation's Cyber Harassment Helpline is toll-free Helpline for victims of online harassment and violence. The Helpline will provide a free service. You can call on toll-free number: 0800-39393 everyday from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Email at helpdesk@digitalrightsfoundation.pk [27]

Rozan Helpline

Rozan is working on issues related to emotional and psychological health, gender, violence against women and children, and the psychological and reproductive health of adolescents. FREE Telephonic Counseling 0800-22444, 0303-4442288 (*Regular charges) Mon-Sat, 10:00 am – 6:00 pm[28]

Protest & March

_during_Aurat_March_2020.jpg)

The first Aurat March (Women's March) was held in Pakistan on 8 March 2018 (in the city of Karachi). In 2019, it was organised in Lahore and Karachi by a women's collective called Hum Auratein (We the Women), and in other parts of the country, including Islamabad, Hyderabad, Quetta, Mardan, and Faislabad, by Women democratic front (WDF), Women Action Forum (WAF), and others.[29] The march was endorsed by the Lady Health Workers Association, and included representatives from multiple women's-rights organizations.[30][31] The march called for more accountability for violence against women, and to support for women who experience violence and harassment at the hands of security forces, in public spaces, at home, and at the workplace.[4] Reports suggest that more and more women rushed to join the march until the crowd was became scattered. Women (as well as men) carried posters bearing phrases such as ‘Ghar ka Kaam, Sab ka Kaam’, and ‘Women are humans, not honour’ became a rallying cry.

On March 8, 2020, the Aurat March procession in Pakistan's capital Islamabad was attacked by religious extremists who were holding a counter-march to celebrate Haya or modesty. It was attended by women from the Jamaat-e-Islami, JUI-F, Lal Masjid, and female students of different seminaries including Jamiat Hafsa, staged as Haya March. Bricks, stones, shoes and sticks were hurled at the peaceful marchers on the Aurat March side, leaving several people injured.[32][33] Earlier even before the March, a van carrying newly-printed banners of Aurat March was stopped and driver beaten. During the March The BBC correspondent Irfana Yasser and her children were assaulted with chilli powder which temporarily blinded them.[34] At least one media camera person hospitalized. Subsequently, the attack was stopped by the police authorities that were present, and the March continued forward despite the opposition.[35][36]

In Lahore, marchers gathered outside the Press Club and passed through Egerton Road to culminate outside Aiwan-e-Iqbal. Participants were holding a plethora of placards. Despite the social media storm before the march, men were present in large numbers in support of the Aurat March. The participants delivered speeches and held placards and banners displaying thought-provoking slogans to raise the pressing issues of gender-based violence including sexual harassment and assault in the workplace, deep-rooted misogyny and the patriarchal mindset prevalent in the society. A resolution was submitted in Punjab Assembly by Kanwal Liaquat (MPA-PMLN), demanding an end to gender discrimination. The resolution condemned under-age marriages and demanded that women be granted legal, social and economic protection.[37]

References

- "Violence against women". www.who.int. WHO. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- Iftikhar, Rukhsana (2019). "Break the Silence: Pakistani Women Facing Violence". Journal of Political Studies (36): 63 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- The world's most dangerous countries for women (2018). Thompson Reuters Foundation. Retrieved March 14th, 2020

- Jafri, Amir H. (2008). Honour killing : dilemma, ritual, understanding. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195476316. OCLC 180753749.

- Gosselin, Denise Kindschi (2009). Heavy Hands: An Introduction to the Crime of Intimate and Family Violence (4th ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 13. ISBN 978-0136139034.

- Hansar, Robert D. (2007). "Cross-Cultural Examination of Domestic Violence in China and Pakistan". In Nicky Ali Jackson (ed.). Encyclopedia of Domestic Violence (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 211. ISBN 978-0415969680.

- Zakar, Rubeena; Zakar, Muhammad; Mikolajczyk, Rafael; Kraemer, Alexander (2013). "Spousal Violence Against Women and Its Association With Women's Mental Health in Pakistan". Health Care for Women International. 34 (9): 795–813. doi:10.1080/07399332.2013.794462. PMID 23790086.

- Aslam, Syeda; Zaheer, Sidra; Shafique, Kashif (2015). "Is Spousal Violence Being "Vertically Transmitted" through Victims? Findings from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012-13". PLoS ONE. 10 (6): e0129790. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129790. PMC 4470804. PMID 26083619.

- Hussain, Rafat; Khan, Adeel (2008-04-28). "Women's Perceptions and Experiences of Sexual Violence in Marital Relationships and Its Effect on Reproductive Health". Health Care for Women International. 29 (5): 468–483. doi:10.1080/07399330801949541. ISSN 0739-9332. PMID 18437595.

- Nasrullah, Muazzam; Haqqi, Sobia; Cummings, Kristin (2009). "The epidemiological patterns of honour killing of women in Pakistan". European Journal of Public Health. 19 (2): 193–197. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckp021. PMID 19286837.

- "'1,000 girls forcibly converted to Islam in Pakistan every year'".

- "Forced conversions torment Pakistan's Hindus". Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Yudhvir Rana (January 30th, 2020). Most marriages between Hindu women and Muslim men result of. Times of India. Retrieved March 3rd, 2020.

- Reuters (24 July 2004). "Pakistan's honour killings enjoy high-level support". Taipei Times. The Liberty Times Group. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- Aleem, Shamim (2013). Women, Peace, and Security: (An International Perspective). p. 64. ISBN 9781483671123.

- Foerstel, Karen (2009). Issues in Race, Ethnicity, Gender, and Class: Selections. Sage. p. 337. ISBN 978-1412979672.

- Reuters (2015-04-10). "Lahore gets first women-only auto-rickshaw to beat 'male pests'". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- Haeri, Shahla (2002). No Shame for the Sun: Lives of Professional Pakistani Women (1st ed.). Syracuse University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0815629603.

- Goodwin, Jan (2002). Price of Honor: Muslim Women Lift the Veil of Silence on the Islamic World. Plume. p. 51. ISBN 978-0452283770.

- "Article: 25 Equality of citizens". The Constitution of Pakistan, 1973 Developed by Zain Sheikh. Pakistan Constitution Law. 10 December 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Human rights ministry launches awareness drive about women's right to inheritance". DAWN.COM. Dawn Newspaper. 14 September 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Forced Marriage" (PDF). NA Pak. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "The Prevention of Anti Women Practices Act 2011 | The Institute for Social Justice (ISJ)". ISJ. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Ministry of Human Rights". www.mohr.gov.pk. MOHR. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Helpline | PCSW". pcsw.punjab.gov.pk. PCSW. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "LEGAL AID". AGHS. AGHS Legal Help. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Cyber Harassment Helpline". Digital Rights Foundation. DRF. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Who We Are | Rozan". rozan.org. ROZAN. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Pakistani women hold 'aurat march' for equality, gender justice". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2019-03-16.

- Saeed, Mehek. "Aurat March 2018: Freedom over fear". www.thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 2019-03-17.

- "A rising movement". dawn.com. 2019-03-18. Retrieved 2019-04-06.

- Javed, Diaa Hadid,Hina. "International Women's Day: With Shoes And Stones, Islamists Disrupt Pakistan Rally". www.capradio.org. Retrieved 2020-03-13.

- "International Women's Day Rallies See Some Violence". www.wkms.org. Retrieved 2020-03-13.

- Yasin, Aamir (2020-03-11). "Aurat March organisers demand judicial probe into Islamabad stone pelting incident". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- "Aurat March attacked with bricks, sticks in Islamabad". www.pakistantoday.com.pk. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- "Readying for the Aftermath". Newsweek Pakistan. 2020-03-11. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- "Aurat March: Women reclaim public spaces on their day". Pakistan Today. 2019-03-09. Retrieved 2020-03-12.