Trophy hunting

Trophy hunting or sport hunting is hunting of wild game for human recreation. The trophy is the animal or part of the animal kept, and usually displayed, to represent the success of the hunt. The game sought is typically a large or impressively ornamented male, such as one having large horns or antlers. Generally, only parts of the animal are kept as a trophies (usually the head, skin, horns or antlers) and the carcass itself is used for food.

Trophies are often displayed in the hunter's home or office, and often in specially designed "trophy rooms", sometimes called "game rooms" or "gun rooms", in which the hunter's weaponry is displayed as well.[1]

Trophy hunting has both firm supporters and strong opponents. Debates surrounding trophy hunting centrally concern not only the question of the morality of recreational hunting and supposed conservation efforts of big-game and ranch hunting, but also the observed decline in animal species that are targets for trophy hunting.

Types of trophy hunting

African trophy hunting

Trophy hunting has been practiced in Africa and is still practiced in many African countries. According to a study sponsored by International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation (CIC) in partnership with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the revenue generated by hunting tourism in seven Southern African Development Communities (SADC) in 2008 was approximately US$190 million.[2] The practice of trophy hunting supersedes that of ranch or farm hunting, but game ranches helped to legitimize trophy hunting as a facet of the tourism industry in Africa. The first game ranches in Africa were established in the 1960s, and the concept quickly grew in proliferation.[3] Statistics from 2000 illustrate that there were approximately 7000 game farms and reservations operating within South Africa, established on about 16 million hectares of land in the country.[4] Game ranches attract wealthy tourists interested in hunting, as well as foreign investors on a large scale.[3]

Economists at Large Report demonstrated how little money actually reaches communities. Jeff Flocken of the International Fund for Animal Welfare, states that "despite the wild claims that trophy hunting brings millions of dollars in revenue to local people in otherwise poor communities, there is no proof of this. The money that does come into Africa from hunting pales in comparison to the billions generated from tourists who come just to watch wildlife. If lions and other animals continue to disappear from Africa, this vital source of income—nonconsumptive tourism—will end, adversely impacting people all over Africa".[5]

However, South African Environmental Affairs Minister, Edna Molewa, contradicts Flocken's conclusions by stating that the hunting industry has contributed millions to South Africa's economy in past years. In the 2010 hunting season, total revenue of approximately R1.1 billion was generated by the local and trophy hunting industries collectively. "This amount only reflects the revenue generated through accommodation and species fees. The true revenue is therefore substantially higher, as this amount does not even include revenue generated through the associated industries as a result of the multiplier effect", according to Molewa.[6] South Africa's canned lion industry however runs the risk of damaging 'Brand South Africa' and it's profitable nature tourism industry.

North American trophy hunting

After the public outcry from the Killing of Cecil the lion, awareness of this sport was raised worldwide. Attention also focussed on North American sport hunting, in particular the cougar. The cougar, also called the mountain lion, puma, or panther, is hunted for sport across its expansive habitat. According to the Washington, the only federally protected populations in the country are the Florida panther and the Eastern cougar, believed to be extinct.[7]

Several states—including Colorado, Utah and Washington—in recent years have proposed an increase in cougar hunting for various reasons, California is currently the only state throughout the West that prohibits cougar hunting.[8]

The Boone and Crockett Club, claim they used the selective harvest of older males to aid in the recovery of many big game species which were on the brink of extinction at the turn of the 20th century. The organization continues to promote this practice today, and monitors conservation success through its Big Game Records data set.[9]

North American trophy hunting should not be confused with canned hunting or "vanity hunting", which involves the shooting of genetically manipulated and selectively bred animals for the sole purpose of collecting an animal for display. The Boone and Crockett Club disavows this practice and actively campaigns against it.[10]

Ranch hunting

Ranch hunting is a form of big-game hunting where the animals hunted are specifically bred on a ranch for trophy hunting purposes.

Many species of game such as the Indian blackbuck, nilgai, axis deer, barasingha, the Iranian red sheep, and variety of other species of deer, sheep, and antelope, as well as tigers and lions and hybrids of these from Africa, Asia, and the Pacific islands were introduced to ranches in Texas and Florida for the sake of trophy hunting.

These animals are typically hunted on a fee for each kill, with hunters paying $4,000 or more to be able to hunt exotic game.[11][12] As many of these species are endangered or threatened in their native habitat, the United States' government requires 10% of the hunting fee to be given to conservation efforts in the areas where these animals are indigenous. Hunting of endangered animals in the United States is normally illegal under the Endangered Species Act, but is permitted on these ranches since the rare animals hunted there are not indigenous to the United States.

The Humane Society of the United States has criticized these ranches and their hunters with the reasoning that they are still hunting endangered animals even if the animals were raised specifically to be hunted.

Game auctions

Game auctions help provide game farms and reserves with their wildlife. These facilities are important in terms of tourism in Africa, one of the continent's largest economic sectors, accounting for almost 5% of South Africa's GDP, for example.[13][4] South Africa in particular is the main tourist destination on the continent, and as a result, hosts a large number of game auctions, farms, and reservations. Game auctions serve as competitive markets that allow farm and reservation owners to bid on and purchase animals for their facilities. Animals purchased at auctions for these purposes are commonly bought directly as game, or are then bred to supply facilities. Animals used for breeding are generally females, which cost more on average than males due to the increased breeding prospects they present.[4] In addition to sex, other factors that contribute to the prices of animals on auction include the demand for particular species (based on their overall rarity) and the costs of maintaining them.[13][4] Animals that receive increased interest from poachers, such as rhinos or elephants due to their ivory horns and tusks, present additional risks to game farm operations, and do not typically sell well at auction. However other herbivores, specifically ungulate species, tend to fetch exponentially higher sums than carnivores.[13] Prices for these animals can reach into the hundreds of thousands in South African rands, equivalent to tens of thousands of American dollars.[13]

Legal standing

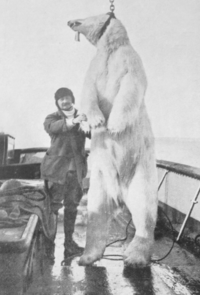

Trophy hunting is legal in many countries [14]; however, there are restrictions on the species that can be hunted, when hunting can take place, and the weapons that can be used. Permits and government consent are also required. Specific laws of trophy hunting vary based on the criteria mentioned, and some areas have even banned trophy hunting all together. Costa Rica, Kenya and Malawi, are amongst the countries which have chosen to ban trophy hunting. Specific laws of trophy hunting usually concern endangered animals in an effort to protect them from extinction. In 1973, the United States passed a law called the Endangered Species Act.[15] This was meant to stop hunting and trafficking of many endangered species in the U.S. that are looked at as prized by many hunters such as the Wood Bison and Polar Bear.[16]

Trophy hunting imports are banned in the Netherlands, France and Australia.

Influence in conservation

In Africa

Trophy hunting was introduced by the British Colonials in an era of plentiful wildlife. It has never been a part of African culture. The Maasai tribes of Kenya and Tanzania have turned their backs on the rite of passage of lion killing and now conserve lions, mindful of the reduced numbers of lions, they decided to reduce the size of their cattle herds.

Some argue it can provide economic incentives to conserve areas for wildlife 'if it pays it stays' and there are some research studies in Conservation Biology,[17] Journal of Sustainable Tourism,[18] Wildlife Conservation by Sustainable Use,[19] and Animal Conservation.[17][20] There are concerns that the same species targeted by trophy hunters are key individuals to their herds. It is now estimated only around 40 great tuskers, elephants with tusks to the ground are left. Mature elephant bulls are now known to be the favoured bulls for breeding females, and to have a stabilising effect on younger males. The trophy hunters favoured lion target is a mature male lion with an impressive mane, these males are 'pride' lions, their loss could equate to as many as 20 lions, as a new pride male will kill cubs when he takes over the pride which has lost it's dominant male lion.

Tanzania has an estimated 40 percent of the population of lions. Its wildlife authorities defend their success in keeping such numbers (as compared to countries like Kenya, where lion numbers have plummeted dramatically) as linked to the use of trophy hunting as a conservation tool. According to Alexander N. Songorwa, director of wildlife for the Tanzanian Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, trophy hunting generated roughly $75 million for Tanzania's economy from 2008 to 2011.[21]

Effects of trophy hunting on animal populations

When poorly managed, trophy hunting can cause negative ecological impacts for the target species such as altered age/sex structures,[22] social disruption,[23][24][25] deleterious genetic effects,[26][27][28] and even population declines in the event of excessive off-takes,[29][30] as well as threaten the conservation[31] and influence the behavior[32] of non-target species. The conservation role of the industry is also hindered by governments and hunting operators that fail to devolve adequate benefits to local communities, reducing incentives for them to protect wildlife,[33][34][35] and by unethical activities, such as shooting from vehicles and canned hunting, conducted by some attract negative press.[36] While locals may hunt certain species as pests, particularly carnivorous species such as leopards, these animals, as well as lions and cougars, are known to exhibit infanticidal tendencies which can be exacerbated by the removal of adult males from their populations.[37] Males are trophy hunted more frequently than females. However, the removal of these males still degrades the networks and groups these species create in order to survive and provide for offspring.[37] Hunting regulations and laws proposing constant proportions or thresholds of community members for these species have been proposed in African nations such as Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe, but are exceptionally difficult to enforce due to the logistics of tracking carnivore populations.[37]

According to the Smithsonian Institution and the World Wildlife Fund, wildlife populations have decreased by an alarming rate of 52% since 1970.[38] This is heavily concentrated on mammals, birds, amphibians and reptiles. The decline is attributed to several reasons including over-exploitation, habitat loss, pollution and climate change.[39]

The graph depicts lion population decline from the 1800s. This information was taken from the National Geographic Big Cats Initiative.

Effects on habitat loss

A 2005 paper by Nigel Leader-Williams and colleagues in the Journal of International Wildlife Law and Policy asserted that the legalization of white rhinoceros hunting in South Africa motivated private landowners to reintroduce the species onto their lands. As a result, white rhinos increased from fewer than one hundred individuals to more than 11,000.[40] Leader-Williams's study also showed that trophy hunting in Zimbabwe doubled wildlife areas relative to state protected areas. The implementation of controlled and legalized hunting led to an increase in the area of suitable land available to elephants and other wildlife, which "reversed the problem of habitat loss and helping to maintain a sustained population increase in Zimbabwe's already large elephant population".[40]

A scientific study in the journal, Biological Conservation by Diogo Andrade, states that trophy hunting is of "major importance to conservation in Africa by creating economic incentives for conservation over vast areas, including areas which may be unsuitable for alternative wildlife-based land uses such as photographic ecotourism".[41] Financial incentives from trophy hunting effectively more than double the land area that is used for wildlife conservation, relative to what would be conserved relying on national parks alone, according to the study published in Biological Conservation.[41]

According to the American writer and journalist Richard Conniff, if Namibia is home to 1,750 of the roughly 5,000 black rhinos surviving in the wild. Namibia's mountain zebra population has increased from 1,000 in 1982 to 27,000 in 2014. Elephants, which are gunned down elsewhere for their ivory, have gone from 15,000 to 20,000 in 1995. Lions, which were on the brink of extinction "from Senegal to Kenya", are increasing in Namibia.[42]

Financial support of conservation efforts

The International Union for Conservation of Nature recognizes that trophy hunting, when well-managed, can generate significant economic incentives for the conservation of target species and their habitats outside of protected areas.[43]

A study published in the journal Animal Conservation[40] and led by Peter Lindsey of Kenya's Mpala Research Centre concluded that most trophy hunters assure that they are concerned about the conservation, ethical, and social issues that hunting raises.[44] The study interviewed 150 Americans who had hunted in Africa before, or who planned to do so within three years. For example, hunters assure that they were much less willing to hunt in areas where African wild dogs or cheetahs were illegally shot than their hunting operators perceived, and they also showed greater concern for social issues than their operators realized, with a huge willingness to hunt in areas were local people lived and benefited from hunting (Fig.1). Eighty-six percent of hunters told the researchers they preferred hunting in an area where they knew that a portion of the proceeds went back into local communities.[40] A certification system could therefore allow hunters to select those operators who benefit local people and conduct themselves in a conservation-friendly manner.[36]

In America

Cougar hunting quotas have had a negative effect on the animals' population. According to Robert Wieglus, director of Large Carnivore Conservation Lab at Washington State University, when too many cougars are killed demographic issues can be seen in the cat's population. The male cougar is extremely territorial and will often seek out females in the territory to both mate and kill any cubs to ensure room for their own offspring. Oftentimes these are young "teenage" males who are hormonal and unpredictable.

These "teenage" lions are mostly responsible for killed livestock and unwanted human interaction. In addition, they often drive females with cubs into hiding or new territory, forcing the females to hunt new prey they did not before.

"Basically the bottom line was this heavy hunting of cougars was actually causing all the problems we were seeing", Wielgus said of his work in Washington.[45]

Economic influence

Perceived economic benefits of trophy hunting

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, trophy hunting "provides an economic incentive" for ranchers to continue to breed those species, and that hunting "reduces the threat of the species' extinction".[46][47]

According to Dr G.C. Dry, former President of Wildlife Ranching South Africa, wildlife ranches have contributed greatly to the South African economy. In his paper "COMMERCIAL WILDLIFE RANCHING’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE GREEN ECONOMY", he states that "commercial wildlife ranching is about appropriate land-use and rural development; it is less about animals per se, not a white affluent issue, not a conservation at-all-cost issue, but about economic sustainability".[48] Dr Dry's paper concludes that "It is a land-use option that is ecologically appropriate, economically sustainable, politically sensitive, and finally, socially just", however no references or sources are provided for the data used.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature reports in "The baby and the bathwater: trophy hunting, conservation and rural livelihoods", that trophy hunting, when well-managed, can be sustainable and generate significant economic incentives for the conservation of target species, but that there are valid concerns about the legality, sustainability and ethics of some hunting practices. The paper concludes that "in some contexts, there may be valid and feasible alternatives to trophy hunting that can deliver the above-mentioned benefits, but identifying, funding and implementing these requires genuine consultation and engagement with affected governments, the private sector and communities.[49]

Regulations, ban and effects

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service imposed a ban on imports. This ban is limited to elephant trophies from Zimbabwe and Tanzania for 2014–2015 and likely going to extend and expand.[45]

In 2001, Botswana instituted a one-year ban on lion hunting.[50] They had previously permitted the hunting of fifty lions each year, which caused a shortage in mature males in the population, as the hunters preferred the lions with the largest manes.[51] After the ban, Safari Club International including prominent member, former President George H. W. Bush successfully lobbied the Botswanan government to reverse the ban.[50][51]

Botswana again banned trophy hunting in 2014, and now villagers claim they get no income from trophy hunters, suffer from damaged crop fields caused by elephants and buffaloes, and lions killing their livestock.[52] Some conservationists claim trophy hunting is more effective for wildlife management than a complete hunting ban.

In the wake of the killing of Cecil the lion, Emirates Airlines, American Airlines, Delta, and United Airlines have all banned the transportation of hunting trophies on flights.

On the contrary, Kenya, which banned trophy hunting in 1977, has seen a 70 percent decline of wild animals according to Laurence Frank, a zoology researcher at the University of California at Berkeley and director of the conservation group Living with Lions. Because the government has no incentive to protect wild animals, effective enforcement on protecting animals has been a disaster according to Frank.[53]

According to a 2012 article by P. Lindsey and G. Balme, if lion hunting was effectively precluded, trophy hunting could potentially become financially unviable across at least 59,538 km2 that could result in a concomitant loss of habitat.

However, the loss of lion hunting could have other potentially broader negative impacts including reduction of competitiveness of wildlife-based land uses relative to ecologically unfavorable alternatives.

Restrictions on lion hunting may also reduce tolerance for the species among communities where local people benefit from trophy hunting, and may reduce funds available for anti-poaching.[54]

Controversy

Opposition

Arguments

Opponents voice strong opinions against trophy hunting based on the belief that it is immoral and lacks financial contribution to the communities affected by trophy hunting and to conservation efforts. National Geographic, for example, published a report in 2015 which says government corruption, especially in Zimbabwe, prevents elephant hunting fees from going towards any conservation efforts, with authorities keeping the fees for themselves. Governments also take more wildlife areas to profit from poaching and trophy hunting. Similarly, a 2017 report by the Australian-based Economists at Large says that trophy hunting amounted to less than one percent of tourism revenue in eight African countries.[55] According to an IUCN report from 2009, surrounding communities in West Africa receive little benefit from the hunting-safari business.[56] Trophy hunting has received a large amount of popular attention internationally as a result of incidents such as the death of Cecil the Lion, garnering a widely negative perception of the practice in many sectors of the general populace.[57] Attention has been drawn both popularly and academically to the ethics of trophy hunting and trophy hunting facilities. Generally speaking, ethical arguments against trophy or sport hunting practices frame them as exploitative and abusive against animals.[57] Evidence has been found illustrating that wild game hunting can also impact the reproductive and social processes of animal species, as well as increase aggression between species members, ultimately impacting the stability of different wildlife communities.[58]

Opponents also cite that the genetic health and social behaviors of species is adversely affected because hunters often kill the largest or most significant male of a species. The removal the most significant animals (because of the size of their horns or mane for example) can severely affect the health of a species population. As Dr Rob Knell states 'Because these high-quality males with large secondary sexual traits tend to father a high proportion of the offspring, their 'good genes' can spread rapidly, so populations of strongly sexually selected animals can adapt quickly to new environments. Removing these males reverses this effect and could have serious and unintended consequences. If the population is having to adapt to a new environment and you remove even a small proportion of these high quality males, you could drive it to extinction.'[59]

Cited from The League Against Cruel Sports "A November 2004 study by the University of Port Elizabeth estimated that eco-tourism on private game reserves generated more than 15 times the income of livestock or game rearing or overseas hunting. (1) Eco-tourism lodges in Eastern Cape Province produce almost 2000 rand (£180) per hectare. Researchers also noted that more jobs were created and staff received "extensive skills training".[60]

A 2011 study published in Conservation Biology found that trophy hunting was the leading factor in the decline of lion populations in Tanzania.[61]

The U.S. House Committee on Natural Resources in 2016 concluded that trophy hunting may be contributing to the extinction of certain animals.[62] The 25 page report is called Missing the Mark.

Nnimmo Bassey, Nigerian environmental activist and director of the Health of Mother Earth Foundation, asserted in November 2017 that "wildlife in Africa have been decimated by trophy hunters".[63]

Conservationist groups such as IFAW and HSUS assert that trophy hunting is a key factor in the "silent extinction" of giraffes.[64]

According to IFAW's analysis of CITES database, 1.7 million animals were killed by trophy hunters between 2004 and 2014, with roughly 200,000 of these being members of threatened species.[65]

Positions

Many of the 189 countries signatory to the 1992 Rio Accord have developed biodiversity action plans that discourage the hunting of protected species.[66]

Trophy hunting is also opposed by the group In Defense of Animals (IDA) on the basis that trophy hunters are not aimed at conservation, they are instead aimed at glory in hunting and killing the biggest and rarest animals. They contend that the trophy hunters are not interested in even saving endangered animals, and are more than willing to pay the very high prices for permits to kill members of an endangered species.[67]

PETA is also opposed to trophy hunting on the basis that it is unnecessary and cruel. The opposition from PETA is on the basis of the moral justification of hunting for sport. The pain that the animals suffer is not justified by the enjoyment that the hunters receive.

The League Against Cruel Sports also opposes trophy hunting for the reason that even if the animal that is being hunted for a trophy is not endangered, it is still unjustified to kill them. They respond to claims of economic benefits as false justifications for the continuance of the inhumane sport.

The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, an elephant conservation organization, believe that elephants bring in significantly more revenue from tourists who want to see them alive. Their 2013 report stated "alive, they benefit local communities and economies; dead they benefit criminal and even terrorist groups".[68][69]

Support

Arguments

Proponents of trophy hunting claim many hunting fees go toward conservation, such as portions of hunting license fees, hunting tags and ammunition taxes. In addition, private groups, such as the National Shooting Sports Foundation, which contributed more than $400,000 in 2005,[70] and smaller private groups also contribute significant funds; for example, the Grand Slam Club Ovis has raised more than $6.3 million to date for the conservation of sheep.[71] Proponents of game and trophy hunting claim that the economic benefits presented by the practice are essential to nations in which ecotourism is not as viable or popular.[72] Additionally, locals in more rural areas of Africa express that there is tension between human communities and certain species that pose dangers to them and their livestock. Members of these communities rely on current hunting regulations that allow them to retaliate or preempt against the threats these species can pose.[37] Programs such as CAMPFIRE (Communal Areas Management Program for Indigenous Resources) in Zimbabwe have been implemented to allow landowners to benefit from the presence of wildlife on their land by marketing it to individuals such as safari owners or game ranch owners, framing wildlife as a renewable resource.[73] Aside from the economic boon presented by the program, CAMPFIRE has also served to mitigate illegal poaching or hunting in certain areas, as well as helping farmers more easily access essential resources that they sometimes have to compete with animal communities for.[73]

Positions

Organizations that support trophy hunting as a tool for conservation include Boone and Crockett Club, The National Wildlife Federation, The Wilderness Society, The Izzaak Walton League of America, North American Wildlife Foundation, Outdoor Writers Association of America, Ducks Unlimited, World Wildlife Fund, The American Forestry Association, Wildlife Legislative Fund of America, Wildlife Management Institute, The Wildlife Society, and IUCN.[74][75][76]

The President of Panthera, a conservation group for big cats and their ecosystems, argues that trophy hunting gives African governments economic incentives to leave safari blocks as wilderness, and that hunting remains the most effective tool to protect wilderness in many parts of Africa.[77][78]

Neutrality

Organizations that are neutral and do not oppose trophy hunting include The National Audubon Society, Defenders of Wildlife, and The Sierra Club[74][75]

Proposed solutions

Certificate system

One proposed solution to these problems is the development of a certification system, whereby hunting operators are rated on three criteria:[36][79]

- Their commitment to conservation, e.g. by adhering to quotas and contributing to anti-poaching efforts.

- How much they benefit and involve local people.

- Whether they comply with agreed ethical standards.

Challenges to the certificate system

Introducing a certification system however remains challenging because it requires co-operation between hunting operators, conservationists and governments.[80][81] It also requires difficult questions to be answered, including; what constitutes ethical hunting? Who constitutes local communities and what represents adequate benefits for them?[36] Some researchers also continue to express concern that allowing trophy hunts for endangered animals might send the wrong message to influential people around the world, perhaps with adverse consequences for conservation. For example, it has been suggested that people will contribute less money to conservation organizations because allowing hunting of a species could suggest that it does not need saving.[82]

In the media

The controversy surrounding trophy hunting was further ignited when an American dentist Walter Palmer gained internet infamy when a picture of him and the dead lion Cecil went viral.[83] Palmer is an experienced and avid big-game hunter and reportedly paid over 50,000 US dollars to hunt and kill the lion.

Cecil the lion was one of the most known and studied lions in Zimbabwe. The lion was lured from the park and, after being injured by an arrow and stalked for 40 hours, Cecil was finally killed. Palmer was reportedly attracted to Cecil's rare black mane. Had Cecil been in the park, it would have been illegal to kill him. The actions the dentist and his hired hunter took in luring out of the park were not endorsed by trophy hunting officials in Zimbabwe. While Zimbabwe courts initially ruled his killing to be illegal, charges were ultimately dropped against the hunter Palmer hired.[84]

Thousands of people went on social media sites to condemn Palmer's actions. Responses included Facebook pages such as "Shame Lion Killer Walter Palmer and River Bluff Dental".

Statistics

Trophy hunters imported over 1.26 million trophies into the United States of America in the 10 years from 2005 to 2014. Canada was the leading source of imported trophies.

From 2005 to 2014 the top ten trophy species imported into the United States were:

- Snow goose 111,366

- Mallard duck 104,067

- Canada goose 70,585

- American black bear 69,072

- Impala 58,423

- Common wildebeest 52,473

- Greater kudu 50,759

- Gemsbok 40,664

- Springbok 34,023

- Bontebok 32,771

From 2005 to 2014 the 'Big Five' trophy species imported into the United States, totaling about 32,500 lions, elephants, rhinos, buffalo, and leopards combined, from Africa were:

Mexico has a hunting industry valued at approximately $200 million with about 4,000 hunting ranches.[85]

Trophies

See also

- Big-game hunting

- Big Five game

- Deer hunting

- Elephant gun

- Fox hunting

- Green hunting

- "The Most Dangerous Game", a classic story famous in the mid twentieth century that was inspired by and explores the philosophy of hunting for sheer pleasure.

- White hunter

- Reindeer hunting in Greenland

- Shooting, shoveling, and shutting up

- International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation (CIC)

- Junta Nacional de Homologación de Trofeos de Caza

References

- Business Week On the hunt for a gun room?: Business celebrates a love of firearms, hunting big animals, Knight Ridder, 10/11/2009 (retrieved 10/11/2009)

- http://www.cic-wildlife.org/fileadmin/Press/Technical_Series/EN/8_.pdf%5B%5D

- Cloete, P. C.; Taljaard, P. R.; Grové, B. (April 2007). "A comparative economic case study of switching from cattle farming to game ranching in the Northern Cape Province". South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 37 (1): 71–78. doi:10.3957/0379-4369-37.1.71. ISSN 0379-4369.

- Van der Merwe, P.; Saayman, M.; Krugell, W. (2004-12-19). "Factors that determine the price of game". Koedoe. 47 (2). doi:10.4102/koedoe.v47i2.86. ISSN 2071-0771.

- "Opinion: Why Are We Still Hunting Lions?". news.nationalgeographic.com. 2013-08-04. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- "Molewa: Hunting brings much to South Africa's economy".

- "Eastern Puma Declared Extinct, Removed From Endangered Species List". Center for Biological Diversity. June 17, 2015.

- SABALOW, RYAN AND PHILLIP REESE. "WHY WE STILL KILL COUGARS: California voters banned mountain lion hunting three decades ago, but the shooting never stopped", The Sacramento Bee (November 3, 2017).

- Boone and Crockett Club. "BIG GAME TROPHIES AND TROPHY HUNTING". Boone and Crockett Club. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- Boone and Crockett Club. "Hunting Ethics". Boone and Crockett Club. Boone and Crockett Club. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- "Exotic Hunting | Texas' Best Exotic Hunting Ranch | V-Bharre Ranch | Texas' Premier Hunting Ranch | V-Bharre Ranch". huntingtexastrophies.com. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- "Texas Exotic Hunting - Texas trophy exotic hunting in West TX". Archived from the original on 2001-12-19. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- Dalerum, Fredrik; Miranda, Maria (2016-02-25). "Game auction prices are not related to biodiversity contributions of southern African ungulates and large carnivores". Scientific Reports. 6 (1). doi:10.1038/srep21922. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 26911226.

- McCarthy, Niall. "The Top Countries For U.S. Trophy Hunters [Infographic]". Forbes. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- Program, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service/Endangered Species. "Endangered Species Program | Laws & Policies | Endangered Species Act | A History of the Endangered Species Act of 1973". www.fws.gov. Retrieved 2018-05-03.

- Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife. "Species Search Results". ecos.fws.gov. Retrieved 2018-05-03.

- C. PACKER; H. BRINK; B. M. KISSUI; H. MALITI; H. KUSHNIR; T. CARO (February 2011). "Effects of Trophy Hunting on Lion and Leopard Populations in Tanzania". Conservation Biology. 25 (1): 143–153. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01576.x. PMID 20825444.

- Baker, Joni E. (1997). "Trophy Hunting as a Sustainable Use of Wildlife Resources in Southern and Eastern Africa". Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 5 (4): 306–321. doi:10.1080/09669589708667294.

- Hurt, Robin; Ravn, Pauline (2000). Hunting and Its Benefits: an Overview of Hunting in Africa with Special Reference to Tanzania. Wildlife Conservation by Sustainable Use. pp. 295–313. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-4012-6_15. ISBN 978-94-010-5773-8.

- P. A. Lindsey; R. Alexander; L. G. Frank; A. Mathieson; S. S. Romañach (August 2006). "Potential of trophy hunting to create incentives for wildlife conservation in Africa where alternative wildlife‐based land uses may not be viable". Animal Conservation. 9 (3): 283–291. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00034.x.

- Songorwa, Alexander N. (2013-03-17). "The New York Times". The New York Times. nytimes.com. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- Milner, JM; Nilsen, EB; Andreassen, HP (2007). "Demographic side effects of selective hunting in ungulates and carnivores". Conservation Biology. 21 (1): 36–47. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00591.x. hdl:11250/134170. PMID 17298509.

- Rasmussen, HB; Okello, JB; Wittemyer, G; Siegismund, HR; Arctander, P; Vollrath, F; et al. (2007). "Age- and tactic-related paternity success in male African elephants". Behavioral Ecology. 19 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1093/beheco/arm093.

- Lindsey, PA; Balme, GA; Funston, P; Henschel, P; Hunter, L; Madzikanda, H; et al. (2013). "The trophy hunting of African lions: scale, current management practices and factors undermining sustainability". PLOS One. 8 (9): 9. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073808. PMC 3776777. PMID 24058491.

- Sogbohossou, E A; Bauer, H; Loveridge, A; Funston, PJ; De Snoo, GR; Sinsin, B; et al. (2014). "Social structure of lions (Panthera leo) is affected by management in Pendjari Biosphere Reserve, Benin". PLOS One. 9 (1): 1. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084674. PMC 3885576. PMID 24416263.

- Crosmary, W-G; Loveridge; Ndaimani, H; Lebel, S; Booth, V; Côté, SD; et al. (2013). "Trophy hunting in Africa: long-term trends in antelope horn size". Animal Conservation. 16 (6): 648–60. doi:10.1111/acv.12043.

- Nuzzo, MC; Traill, LW (2013). "What 50 years of trophy hunting records illustrate for hunted African elephant and bovid populations". African Journal of Ecology. 52 (2): 250–253. doi:10.1111/aje.12104.

- Festa-Bianchet, M; Pelletier, F; Jorgenson, JT; Feder, C; Hubbs, A (2014). "Decrease in horn size and increase in age of trophy sheep in Alberta over 37 years". Journal of Wildlife Management. 78 (1): 133–41. doi:10.1002/jwmg.644.

- Loveridge, A; Searle, A; Murindagomo, F; Macdonald, D (2007). "The impact of sport-hunting on the population dynamics of an African lion population in a protected area". Biological Conservation. 134 (4): 548–58. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.09.010.

- Packer, C; Brink, H; Kissui, BM; Maliti, H; Kushnir, H; Caro, T (2011). "Effects of trophy hunting on lion and leopard populations in Tanzania". Conservation Biology. 25 (1): 142–53. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01576.x. PMID 20825444.

- Hussain, S (2003). "The status of the snow leopard in Pakistan and its conflict with local farmers". Oryx. 37 (1): 26–33. doi:10.1017/s0030605303000085.

- Grignolio, S; Merli, E; Bongi, P; Ciuti, S; Apollonio, M (2010). "Effects of hunting with hounds on a non-target species living on the edge of a protected area". Biological Conservation. 144 (1): 641–649. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.10.022.

- Nelson, F; Nshala, R; Rodgers, WA (2007). "The Evolution and Reform of Tanzanian Wildlife Management". Conservation & Society. 5 (2): 232–261. Archived from the original on 2014-11-06.

- Booth VR. (2010). Contribution of Hunting Tourism: How Significant Is This to National Economies. Joint publication of FAO and CIC.

- Campbell R. (2013). The $200 million question. How much does trophy hunting really contribute to African communities? A report for the African Lion Coalition. Economists at large, Melbourne, Australia.

- Lindsey, PA; Frank, LG; Alexander, R; Mathieson, A; Romañach, SS (2007). "Trophy hunting and conservation in Africa: problems and one potential solution". Conservation Biology. 21 (3): 880–3. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00594.x. PMID 17531065.

- Packer, Craig; Kosmala, Margaret; Cooley, Hilary S.; Brink, Henry; Pintea, Lilian; Garshelis, David; Purchase, Gianetta; Strauss, Megan; Swanson, Alexandra (2009-06-17). "Sport Hunting, Predator Control and Conservation of Large Carnivores". PLOS ONE. 4 (6): e5941. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005941. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2691955. PMID 19536277.

- "Wildlife Around the World Has Decreased 50% Since 1970". Smithsonian Magazine. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "Living Planet Report 2016: Summary" (PDF). WWF. 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- http://conservationmagazine.org/2014/01/can-trophy-hunting-reconciled-conservation/

- P.A. Lindsey; P.A. Roulet; S.S. Romañach (February 2007). "Economic and conservation significance of the trophy hunting industry in sub-Saharan Africa". Biological Conservation. 134 (4): 455–469. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.09.005.

- Conniff, Richard (2014-01-20). "Opinion | A Trophy Hunt That's Good for Rhinos". The New York Times.

- IUCN Species Survival Commission (2012). Guiding Principles on Trophy Hunting as a Tool for Creating Conservation Incentives.

- Lindsey, PA; Alexander, R; Frank, LG; Mathieson, A; Romanach, SS (2006). "Potential of trophy hunting to create incentives for wildlife conservation in Africa where alternative wildlife-based land uses may not be viable". Conservation Biology. 9 (3): 283–291. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00034.x.

- Cruise, Adam (2015-11-17). "Is Trophy Hunting Helping Save African Elephants?". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- http://www.fws.gov/policy/library/2005/05-17432.pdf

- "Can hunting endangered animals save the species?".

- http://www.sawma.co.za/images/Dry_Gert_Full_paper.pdf

- https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/trophy_hunting_conservation_and_rural_livelihoods.pdf

- Theroux, Paul (April 5, 2004). Dark Star Safari: Overland from Cairo to Capetown. Mariner Books. p. 414.

- McGreal, Chris (27 Apr 2001). "Lions face new threat: they're rich, American and they've got guns". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Onishi, Norimitsu (2015-09-12). "A Hunting Ban Saps a Village's Livelihood". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- "Opinion | the Ethics of Safari Hunting in Africa". The New York Times. 2014-07-03.

- Lindsey, PA; Balme, GA; Booth, VR; Midlane, N (2012). "PLOS ONE: The Significance of African Lions for the Financial Viability of Trophy Hunting and the Maintenance of Wild Land". PLOS ONE. 7 (1): e29332. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029332. PMC 3256150. PMID 22247772.

- Ingraham, Christopher (November 17, 2017). "The Fish and Wildlife Service said we have to kill elephants to help save them. The data says otherwise". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- Morell, Virginia (November 18, 2017). "What Trophy Hunting Does to the Elephants It Leaves Behind". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- Batavia, Chelsea; Nelson, Michael Paul; Darimont, Chris T.; Paquet, Paul C.; Ripple, William J.; Wallach, Arian D. (2018-05-09). "The elephant (head) in the room: A critical look at trophy hunting". Conservation Letters. 12 (1): e12565. doi:10.1111/conl.12565. ISSN 1755-263X.

- Davidson, Zeke; Valeix, Marion; Loveridge, Andrew J.; Madzikanda, Hillary; Macdonald, David W. (January 2011). "Socio-spatial behaviour of an African lion population following perturbation by sport hunting". Biological Conservation. 144 (1): 114–121. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.08.005. ISSN 0006-3207.

- Briggs, Helen (2017-11-29). "Trophy hunting removes 'good genes'". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-11-30.

- Morley MP, Elliott (Dec 2004). The Myth of Trophy Hunting as Conservation. Website: The League Against Cruel Sports.

- Packer, C.; Brink, H.; Kissui, B.M.; Maliti, H.; Kushnir, H.; Caro, T (2011). "Effects of Trophy Hunting on Lion and Leopard Populations in Tanzania". Conservation Biology. 25 (1): 142–153. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01576.x. PMID 20825444.

- Smith, Jada F. (June 13, 2016). "Trophy Hunting Fees Do Little to Help Threatened Species, Report Says". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- "African Activist Slams Trump for Reversing Ban on Elephant Trophies from Hunts in Zimbabwe & Zambia". Democracy Now!. November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- Milman, Oliver (April 19, 2017). "Giraffes must be listed as endangered, conservationists formally tell US". The Guardian. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- Flocken, Jeffrey (June 14, 2016). "Killing for Trophies: Report analyses trophy hunting around the world". ifaw.org. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- "Arguments against trophy hunting". Archived from the original on 2015-07-10. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- "Trophy Hunting - - In Defense of Animals". - In Defense of Animals. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- Ebbs, Stephanie (November 17, 2017). "Does hunting elephants help conserve the species?". ABC News. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- "Dead or Alive? Valuing an Elephant" (PDF). iworry.org. David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust. 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- State Agencies Receive Over $420,000 in Grants Through Hunting Heritage Partnership

- Grand Slam Club Ovis

- Lindsey, P. A.; Alexander, R.; Frank, L. G.; Mathieson, A.; Romanach, S. S. (August 2006). "Potential of trophy hunting to create incentives for wildlife conservation in Africa where alternative wildlife-based land uses may not be viable". Animal Conservation. 9 (3): 283–291. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00034.x. ISSN 1367-9430.

- Frost, Peter G.H.; Bond, Ivan (May 2008). "The CAMPFIRE programme in Zimbabwe: Payments for wildlife services". Ecological Economics. 65 (4): 776–787. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.09.018. ISSN 0921-8009.

- "What They Say About Hunting" (PDF). National Shooting Sports Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-08-07. Retrieved 2016-10-13.

- "Wildlife Organizations: Positions on Hunting".

- http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/iucn_informingdecisionsontrophyhuntingv1.pdf

- http://www.panthera.org/node/1253

- http://www.panthera.org/node/249

- Lewis D & Jackson J. (2005). Safari hunting and conservation on communal land in southern Africa. Pages 239–251 in R. Woodroffe, S. Thirgood, and A. Rabinowitz, editors. People and wildlife: conflict or coexistence? Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- Nelson, F; Lindsey, PA; Balme, G (2013). "hunting and lion conservation: a question of governance?". Oryx. 47 (4): 501–509. doi:10.1017/s003060531200035x.

- Selier, SJ; Page, BR; Vanak, AT; Slotow, R (2014). "Sustainability of elephant hunting across international borders in southern Africa: A case study of the greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier Conservation Area". Journal of Wildlife Management. 78 (1): 122–132. doi:10.1002/jwmg.641.

- Buckley, R (2014). "Mixed signals from hunting rare wildlife". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 12 (6): 321–322. doi:10.1890/14.WB.008. hdl:10072/62747.

- "American Public Roars After It Gets a Glimpse of International Trophy Hunting of Lions · A Humane Nation". A Humane Nation. 2015-07-29. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- "Charges Dropped Against Professional Hunter". National Geographic. 11 November 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- Bale, Rachael (2016-02-06). "Exclusive: Hard Data Reveal Scale of America's Trophy-Hunting Habit". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- Yahya M. Musakhel 2005: Identification of Biodiversity hotspots in Musakhel district Balochistan Pakistan.

Further reading

- Books

- Foa, E. After Big Game in Central Africa. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-03274-9.

- Journal articles

- Simon, Alexander. Against Trophy Hunting - A Marxian-Leopoldian Critique (September 2016), Monthly Review

- Paterniti, Michael. Should We Kill Animals to Save Them? (October 2017) National Geographic

- Other

External links

| Look up trophy hunting in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Trophy hunting: Killing or conservation? - CBSN documentary

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hunting trophies. |