Translations of The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien, written originally in English, has since been translated, with varying degrees of success, into dozens of other languages. Tolkien, an expert in Germanic philology, scrutinized those that were under preparation during his lifetime, and made comments on early translations that reflect both the translation process and his work. To aid translators, and because he was unhappy with some choices made by early translators such as Åke Ohlmarks,[1] Tolkien wrote his Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings in 1967 (released publicly in 1975 in A Tolkien Compass, and in full in 2005, in The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion).

Challenges to translation

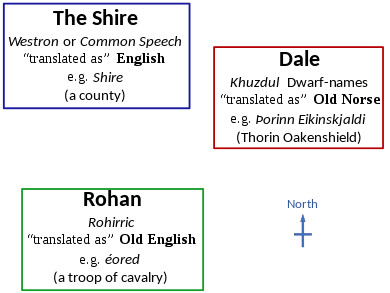

Because The Lord of the Rings purports to be a translation of the Red Book of Westmarch, with the English language in the translation purporting to represent the Westron of the original, translators need to imitate the complex interplay between English and non-English (Elvish) nomenclature in the book. An additional difficulty is the presence of proper names in Old English and Old Norse. Tolkien chose to use Old English for names and some words of the Rohirrim, for example, "Théoden", King of Rohan: his name is simply a transliteration of Old English þēoden, "king". Similarly, he used Old Norse for "external" names of his Dwarves, such as "Thorin Oakenshield": both Þorinn and Eikinskjaldi are Dwarf-names from the Völuspá.[2]

The relation of such names to English, within the history of English, and of the Germanic languages more generally, is intended to reflect the relation of the purported "original" names to Westron. The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey states that Tolkien began with the words and names that he wanted, and invented parts of Middle-earth to resolve the linguistic puzzle he had accidentally created by using different European languages for those of peoples in his legendarium.[2]

Early translations

The first translations of The Lord of the Rings to be prepared were those in Dutch (1956-7, Max Schuchart) and Swedish (1959–60, Åke Ohlmarks). Both took considerable liberties with their material, apparent already from the rendition of the title, In de Ban van de Ring "Under the Spell of the Ring" and Sagan om Ringen "The Tale of the Ring", respectively.

Most later translations, beginning with the Polish Władca Pierścieni in 1961, render the title more literally. Later non-literal title translations however include the Japanese 指輪物語 (Hepburn: Yubiwa Monogatari) "Legend of the Ring", Finnish Taru Sormusten Herrasta "Legend of the Lord of the Rings", the first Norwegian translation Krigen om ringen "The War of the Ring", Icelandic Hringadróttinssaga "The Lord of the Rings' Saga", and West Frisian, Master fan Alle Ringen "Master of All Rings".

Tolkien in both the Dutch and the Swedish case objected strongly while the translations were in progress, in particular regarding the adaptation of proper names. Despite lengthy correspondence, Tolkien did not succeed in convincing the Dutch translator of his objections, and was similarly frustrated in the Swedish case.

Dutch translation (Schuchart)

Regarding the Dutch version of Max Schuchart, In de Ban van de Ring, Tolkien wrote

In principle I object as strongly as is possible to the 'translation' of the nomenclature at all (even by a competent person). I wonder why a translator should think himself called on or entitled to do any such thing. That this is an 'imaginary' world does not give him any right to remodel it according to his fancy, even if he could in a few months create a new coherent structure which it took me years to work out. [...] May I say at once that I will not tolerate any similar tinkering with the personal nomenclature. Nor with the name/word Hobbit.

— 3 July 1956, to Rayner Unwin, Letters, #190, pp. 249-51

However, if one reads the Dutch version, little has changed except the names of certain characters. This to ensure that no reading difficulties emerge for Dutchmen who don't speak English. Schuchart's translation as of 2008 remains the only authorized translation in Dutch. However, there is an unauthorized translation by E.J. Mensink-van Warmelo, dating from the late 1970s.[3] A revision of Schuchart's translation was initiated in 2003, but the publisher Uitgeverij M decided against publication of the revised version.

Swedish translation (Ohlmarks)

Åke Ohlmarks was a prolific translator, who during his career besides Tolkien published Swedish versions of Shakespeare, Dante and the Qur'an. Tolkien intensely disliked Ohlmarks' translation of The Lord of the Rings (Sagan om ringen), however, more so even than Schuchart's Dutch translation.

Ohlmarks' translation remained the only one available in Swedish for forty years, and until his death in 1984, Ohlmarks remained impervious to the numerous complaints and calls for revision from readers.

After The Silmarillion was published in 1977, Christopher Tolkien consented to a Swedish translation only on the condition that Ohlmarks have nothing to do with it. After a fire at his home in 1982, Ohlmarks incoherently charged Tolkien fans with arson, and subsequently published the book Tolkien och den svarta magin (Tolkien and the black magic) - a book connecting Tolkien with "black magic" and Nazism.[4]

Ohlmarks' translation was superseded only in 2005, by a new translation by Erik Andersson with poems interpreted by Lotta Olsson.[5]

German translations

As a reaction to his disappointment with the Dutch and Swedish translations, Tolkien wrote his Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings and subsequently gained himself a larger influence on translations into other Germanic languages, namely the Danish and the German version. Frankfurt-based Margaret Carroux qualified for the German version published by Klett-Cotta on basis of her translation of Tolkien's short story Leaf by Niggle, that she had translated solely to give him a sample of her work. In her preparation for The Lord of the Rings (Der Herr der Ringe), unlike Schluchart and Ohlmarks, Carroux even visited Tolkien in Oxford with a suitcase full of his published works and questions about them. Yet, mainly due to a cold that both Tolkien and his wife were going through at the time, the meeting was later described as inhospitable and 'chilly', Tolkien being 'harsh', 'taciturn' and 'severely ill'.[6] Later correspondences with Carroux turned out to be much more encouraging with Tolkien being generally very pleased with Carroux's work, with the sole exception of the poems and songs, that would eventually be translated by poet Ebba-Margareta von Freymann.

On several instances Carroux departed from literal translations, e.g. for the Shire. Tolkien endorsed the Gouw of the Dutch version and remarked that German Gau "seems to me suitable in Ger., unless its recent use in regional reorganization under Hitler has spoilt this very old word."

Carroux decided that this was indeed the case, and opted for the more artificial Auenland "meadow-land" instead.

"Elf" especially was rendered with linguistic care as Elb, the plural Elves as Elben. The choice reflects Tolkien's suggestion:

With regard to German: I would suggest with diffidence that Elf, elfen, are perhaps to be avoided as equivalents of Elf, elven. Elf is, I believe, borrowed from English, and may retain some of the associations of a kind that I should particularly desire not to be present (if possible): e.g. those of Drayton or of A Midsummer Night's Dream [...] I wonder whether the word Alp (or better still the form Alb, still given in modern dictionaries as a variant, which is historically the more normal form) could not be used. It is the true cognate of English elf [...] The Elves of the 'mythology' of The L.R. are not actually equatable with the folklore traditions about 'fairies', and as I have said (Appendix F[...]) I should prefer the oldest available form of the name to be used, and leave it to acquire its own associations for readers of my tale.

The Elb chosen by Carroux instead of the suggested Alb is a construction by Jacob Grimm in his 1835 Teutonic Mythology. Grimm, like Tolkien, notes that German Elf is a loan from the English, and argues for the revival of the original German cognate, which survived in the adjective elbisch and in composed names like Elbegast. Grimm also notes that the correct plural of Elb would be Elbe, but Carroux does not follow in this and uses the plural Elben, denounced by Grimm as incorrect in his German Dictionary (s.v. Alb).

On many instances, though, the German version resorts to literal translations. Rivendell Tolkien considered as a particularly difficult case, and recommended to "translate by sense, or retain as seems best.", but Carroux opted for the literal Bruchtal. The name "Baggins" was rendered as Beutlin (containing the word Beutel meaning "bag").

Another case where Carroux translated the meaning rather than the actual words was the name of Shelob, formed from the pronoun she plus lob, a dialectal word for "spider" (according to Tolkien; the OED is only aware of its occurrence in Middle English). Tolkien gives no prescription; he merely notes that "The Dutch version retains Shelob, but the Swed. has the rather feeble Honmonstret ["she-monster"]." Carroux chose Kankra, an artificial feminine formation from dialectal German Kanker "Opiliones" (cognate to cancer).

In 2000, Klett-Cotta published a new translation of The Lord of the Rings by Wolfgang Krege, not as a replacement of the old one, which throughout the years had gained a loyal following, but rather as an accompaniment. The new version focuses more on the differences in linguistic style that Tolkien employed to set apart the more biblical prose and the high style of elvish and human 'nobility' from the more colloquial 1940s English spoken by the Hobbits, something that he thought Carroux's more unified version was lacking. Krege's translation met mixed reception, the general argument of critics being that he took too many liberties in modernising the language of the Hobbits with the linguistic style of late 90s German that not only subverted the epic style of the narrative as a whole but also went beyond the stylistic differences intended by Tolkien. Klett-Cotta has continued to offer and continuously republishes both translations. Yet, for the 2012 republication of Krege's version, his most controversial decisions had been reverted in parts.

Russian translations

Interest in Russia awoke soon after the publication of The Lord of the Rings in 1955, long before the first Russian translation. A first effort at publication was made in the 1960s, but in order to comply with literary censorship in Soviet Russia, the work was considerably abridged and transformed. The ideological danger of the book was seen in the "hidden allegory 'of the conflict between the individualist West and the totalitarian, Communist East'" (Markova 2006), while, ironically, Marxist readings in the west conversely identified Tolkien's anti-industrial ideas as presented in the Shire with primitive communism, in a struggle with the evil forces of technocratic capitalism.

Russian translations of The Lord of the Rings circulated as samizdat and were published only after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but then in great numbers; no less than ten official Russian translations appeared between 1990 and 2005 (Markova 2006). Tolkien fandom grew especially rapidly during the early 1990s at Moscow State University. Many unofficial and incomplete translations are in circulation. The first translation appearing in print was that by Kistyakovski and Muravyov (volume 1, published 1982).

Hebrew

The first translation of The Lord of the Rings into Hebrew (שר הטבעות) was done by Canaanite movement member Ruth Livnit, aided by Uriel Ofek as the translator of the verse. The 1977 version was considered a unique book for the sort of Hebrew that was used therein, until it was revised by Dr. Emanuel Lottem according to the second English edition, although still under the name of the previous translators, with Lottem as merely "The editor".[7]

The difference between the two versions is clear in the translation of names with the book:

Elves, for an example, were first translated as "בני לילית" (Bneyi Lilith, i.e. the "Children of Lilith") but in the new edition was transcribed in the form of "Elefs" maintained through Yiddish as "עלף". The change was made because "Bneyi Lilith" essentially relates with Babylonian-derived Jewish folklore character of Lilith, mother of all demons, an inappropriate name for Tolkien's Elves.[8] Since the whole seven appendices and part of the foreword were dropped in the first edition, the rules of transcript therein were not kept. In the New edition Dr. Lottem translated the appendices by himself, and transcribed names according to the instructions therein. Furthermore, the old translation was made without any connection to the rest of Tolkien's mythological context, not The Silmarillion nor even The Hobbit. Parts of the story relating to events mentioned in the above books were not understood and therefore either translated inaccurately, or even dropped completely. There are also major inconsistencies in transcript or in repetitions of similar text within the story, especially in the verse.[9]

Tolkien's Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings

The Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings is a guideline on the nomenclature in The Lord of the Rings compiled by J. R. R. Tolkien in 1966 to 1967, intended for the benefit of translators, especially for translations into Germanic languages. The first translations to profit from the guideline were those into Danish (Ida Nyrop Ludvigsen) and German (Margaret Carroux), both appearing 1972.

Frustrated by his experience with the Dutch and Swedish translations, Tolkien asked that

when any further translations are negotiated, [...] I should be consulted at an early stage. [...] After all, I charge nothing, and can save a translator a good deal of time and puzzling; and if consulted at an early stage my remarks will appear far less in the light of peevish criticisms.

— Letter of 7 December 1957 to Rayner Unwin, Letters, p. 263

With a view to the planned Danish translation, Tolkien decided to take action in order to avoid similar disappointments in the future. On 2 January 1967, he wrote to Otto B. Lindhardt, of the Danish publisher Gyldendals Bibliotek:

I have therefore recently been engaged in making, and have nearly completed, a commentary on the names in this story, with explanations and suggestions for the use of a translator, having especially in mind Danish and German.

Photocopies of this "commentary" were sent to translators of The Lord of the Rings by Allen & Unwin from 1967. After Tolkien's death, it was published as Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings, edited by Christopher Tolkien in A Tolkien Compass (1975). Hammond and Scull (2005) have newly transcribed and slightly edited Tolkien's typescript, and re-published it under the title of Nomenclature of The Lord of the Rings in their book The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion.

Tolkien uses the abbreviations CS for "Common Speech, in original text represented by English", and LT for the target language of the translation. His approach is the prescription that if in doubt, a proper name should not be altered but left as it appears in the English original:

All names not in the following list should be left entirely unchanged in any language used in translation (LT), except that inflexional s, es should be rendered according to the grammar of the LT.

The names in English form, such as Dead Marshes, should in Tolkien's view be translated straightforwardly, while the names in Elvish should be left unchanged. The difficult cases are those names where

the author, acting as translator of Elvish names already devised and used in this book or elsewhere, has taken pains to produce a CS name that is both a translation and also (to English ears) a euphonious name of familiar English style, even if it does not actually occur in England.

An example of such a case is Rivendell, the translation of Sindarin Imladris "Glen of the Cleft", or Westernesse, the translation of Númenor. The list gives suggestions for "old, obsolescent, or dialectal words in the Scandinavian and German languages".

The Danish (Ludvigsen) and German (Carroux) translations were the only ones profiting from Tolkien's "commentary" to be published before Tolkien's death in 1973. Since then, throughout the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s and 2010s, new translations into numerous languages have continued to appear.

List of translations

The number of languages into which Tolkien's works has been translated is subject to some debate. HarperCollins explicitly lists 38 (or 39) languages for which translations of "The Hobbit and/or The Lord of the Rings" exist:

- Basque, Breton, Bulgarian, Catalan, Chinese (Simplified and Traditional), Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, Estonian, Finnish, French, Galician, German, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Icelandic, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Latvian, Lithuanian, Marathi, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese (European, Brazilian), Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Swedish, Thai, Turkish, Ukrainian, Vietnamese.[10]

For some of these languages, there is a translation of The Hobbit, but not of The Lord of the Rings. For some languages, there is more than one translation of The Lord of the Rings. These notably include Russian, besides Swedish, Norwegian, German, Polish, Slovenian, and Korean.

In addition to languages mentioned above, there are published translations of the Hobbit into Albanian, Arabic, Armenian, Belarusian, Esperanto, Faroese, Georgian, Hawaiian, Irish, Luxembourgish, Macedonian, and Persian.[11]

Comparatively few translations appeared during Tolkien's lifetime: when Tolkien died on 2 September 1973, the Dutch, Swedish, Polish, Italian, Danish, German and French translations had been published completely, and the Japanese and Finnish ones in part. The Russian translations are a special case because many unpublished and unauthorized translations circulated in the 1970s and 1980s Soviet Union, which were gradually published from the 1990s.

| language | title | year | translator | publisher | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch | In de Ban van de Ring | 1957 | Max Schuchart | Het Spectrum, Utrecht | N/A |

| Swedish | Sagan om ringen | 1959 to 1961 | Åke Ohlmarks | Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm | ISBN 978-91-1-300998-8 |

| Polish | Władca Pierścieni | 1961 to 1963 | Maria Skibniewska (poems by Włodzimierz Lewik and Andrzej Nowicki)) | Czytelnik, Warsaw | N/A |

| Italian | Il Signore degli Anelli | 1967 to 1970 | Vittoria Alliata di Villafranca | Bompiani, Milan | ISBN 9788845210273 |

| Danish | Ringenes Herre | 1968 to 1972 | Ida Nyrop Ludvigsen[12] | Gyldendal, Copenhagen | ISBN 978-87-02-04320-4 |

| German | Der Herr der Ringe | 1969 to 1970 | Margaret Carroux and Ebba-Margareta von Freymann (poems) | Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart | ISBN 978-3-608-93666-7 |

| French | Le Seigneur des anneaux | 1972 to 1973 | Francis Ledoux | Christian Bourgois | ISBN 9782266201728 |

| Japanese | Yubiwa Monogatari (指輪物語, lit. "The tale of the Ring(s)") | 1972 to 1975 | Teiji Seta (瀬田貞二) and Akiko Tanaka (田中明子) | Hyouronsha(評論社), Tokyo | ISBN 978-4-566-02350-5, ISBN 978-4-566-02351-2, ISBN 978-4-566-02352-9 |

| Finnish | Taru sormusten herrasta | 1973 to 1975 | Kersti Juva, Eila Pennanen, Panu Pekkanen | N/A | N/A |

| Norwegian (Bokmål) | Krigen om ringen | 1973 to 1975 | Nils Werenskiold | Tiden Norsk Forlag | ISBN 82-10-00816-1, ISBN 82-10-00930-3, ISBN 82-10-01096-4 |

| Portuguese | O Senhor dos Anéis | 1975 to 1979 | António Rocha and Alberto Monjardim | Publicações Europa-América | ISBN 978-972-1-04102-8, ISBN 978-972-1-04144-8, ISBN 978-972-1-04154-7 |

| Russian | Властелин колец Vlastelin kolec | 1976 (publ. 2002) | A. A. Gruzberg | N/A | N/A |

| Spanish | El Señor de los Anillos | 1977 to 1980 | Luis Domènech (Francisco Porrúa) and Matilde Horne | Minotauro Buenos Aires | ISBN 84-450-7032-0 (Minotauro) |

| Greek | Ο Άρχοντας των Δαχτυλιδιών O Archontas ton Dachtylidion | 1978 | Eugenia Chatzithanasi-Kollia | Kedros, Athens | ISBN 960-04-0308-2 |

| Hebrew | שר הטבעות Sar ha-Tabbaot | 1979 to 1980 | Ruth Livnit | Zmora-Bitan, Tel Aviv | N/A |

| Norwegian (Bokmål) | Ringenes herre | 1980 to 1981 | Torstein Bugge Høverstad | Tiden Norsk Forlag | ISBN 978-82-10-04449-6 |

| Hungarian | A Gyűrűk Ura | 1981 | Chapters 1-11: Ádám Réz Rest: Árpád Göncz and Dezső Tandori (poems) | Gondolat Könyvkiadó (1981) Európa Könyvkiadó (since 1990), Budapest | First: ISBN 963-280-963-7, ISBN 963-280-964-5, ISBN 963-280-965-3 2008 reworked: ISBN 978-963-07-8646-1[13] |

| Serbian | Господар Прстенова Gospodar Prstenova | 1981[14] | Zoran Stanojević | Nolit, Belgrade | N/A |

| Russian | Властелин колец Vlastelin kolec | 1982 to 1992 | V. S. Muravev (2nd to 6th books, poems), A. A. Kistyakovskij (first book) | Raduga, Moscow | ISBN 5-05-002255-X, ISBN 5-05-002397-1, ISBN 5-05-004017-5 |

| Russian | Властелин колец Vlastelin kolec | 1984 (publ. 1991) | H. V. Grigoreva and V. I. Grushetskij and I. B. Grinshpun (poems) | Severo-Zapad | ISBN 5-7183-0003-8, ISBN 5-352-00312-4 (Azbuka) |

| Catalan | El Senyor dels Anells | 1986 to 1988 | Francesc Parcerisas | Vicens Vives, Barcelona | ISBN 84-316-6868-7 |

| Korean | 반지이야기 (Banjiiyagi), (reprinted as 완역 반지제왕 (Wanyeok Banjijewang)) | 1988 to 1992 | 강영운 (Kang Yeong-un) | Dongsuh Press, Seoul | N/A |

| Armenian | Պահապաննէրը Pahapannērë | 1989 | Emma Makarian | Arevnik, Yerevan | Only The Fellowship of the Ring, no ISBN |

| Korean | 반지전쟁 (Banjijeonjaeng), (reprinted as 반지의 제왕 (Banjieui Jewang)) | 1990 | 김번, 김보원, 이미애 (Kim Beon, Kim Bo-won, Lee Mi-ae) | Doseochulpan Yemun, Seoul | ISBN 8986834200, ISBN 8986834219, ISBN 8986834227 |

| Russian | Повесть о Кольце Povest' o Kol'tse | 1990 | Z.A. Bobyr' | Interprint | no ISBN Condensed translation |

| Bulgarian | Властелинът на пръстените Vlastelinăt na prăstenite | 1990 to 1991 | Lyubomir Nikolov | Narodna Kultura Sofia | N/A |

| Czech | Pán Prstenů | 1990 to 1992 | Stanislava Pošustová | Mladá fronta, Prague | ISBN 80-204-0105-9, ISBN 80-204-0194-6, ISBN 80-204-0259-4 |

| Russian | Властелин колец Vlastelin kolec | 1991 | V.A.M. (Valeriya Aleksandrovna Matorina) | Amur, Khabarovsk | N/A |

| Korean | 마술반지 (Masulbanji) | 1992 to 1994 | 이동진 (Lee Dong-jin) | Pauline (Baorottal), Seoul | Only The Fellowship of the Ring and The Two Towers. ISBN 8933103422 (first volume) |

| Icelandic | Hringadróttinssaga | 1993 to 1995 | Þorsteinn Thorarensen and Geir Kristjánsson (poems) | Fjölvi, Reykjavík | N/A |

| Lithuanian | Žiedų valdovas | 1994 | Andrius Tapinas and Jonas Strielkūnas | Alma littera, Vilnius | ISBN 9986-02-038-7, ISBN 9986-02-487-0, ISBN 9986-02-959-7 |

| Portuguese (BRA) | O Senhor dos Anéis | 1974 to 1979 | Antônio Ferreira da Rocha and Luiz Alberto Monjardim | Artenova | N/A |

| 1994 | Lenita Maria Rimoli Esteves and Almiro Pisetta | Martins Fontes | ISBN 85-336-0292-8 | ||

| 2019 | Ronald Kyrmse | HarperCollins Brasil | ISBN 978-8595086357 | ||

| Russian | Властелин колец Vlastelin kolec | 1994 | Mariya Kamenkovich and Valerij Karrik | Terra-Azbuka, St. Petersburg | ISBN 5-300-00027-2, ISBN 5-300-00026-4 |

| Croatian | Gospodar prstenova | 1995 | Zlatko Crnković | Algoritam | ISBN 953-6166-05-4 |

| Slovenian | Gospodar prstanov | 1995 | Polona Mertelj, Primož Pečovnik, Zoran Obradovič | Gnosis-Quarto, Ljubljana | |

| Esperanto | La Mastro de l' Ringoj | 1995 to 1997, 2nd ed. 2007 | William Auld | Sezonoj, Yekaterinburg, Kaliningrad | ISBN 5745004576, ISBN 9785745004575 |

| Polish | Władca Pierścieni | 1996 to 1997 | Jerzy Łozinski and Marek Obarski (poems) | Zysk i S-ka, Poznań | ISBN 8371502419, ISBN 8371502427, ISBN 8371502435 |

| Estonian | Sõrmuste Isand | 1996 to 1998 | Ene Aru and Votele Viidemann | Tiritamm, Tallinn | ISBN 9985-55-039-0, ISBN 9985-55-046-3, ISBN 9985-55-049-8 |

| Turkish | Yüzüklerin Efendisi | 1996 to 1998 | Çiğdem Erkal İpek, Bülent Somay (poems) | Metis, İstanbul | ISBN 975-342-347-0 |

| Romanian | Stăpânul Inelelor | 1999 to 2001 | Irina Horea, Gabriela Nedelea, Ion Horea | Editorial Group Rao | N/A |

| German | Der Herr der Ringe | 2000 | Wolfgang Krege | Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart | ISBN 978-3-608-93639-1 |

| Korean | 반지의 제왕 (Banjieui Jewang) | 2001 | 한기찬 (Han Ki-chan) | 황금가지 (Hwanggeum Gaji), Seoul | 6 volumes. ISBN 8982732888, ISBN 8982732896, ISBN 898273290X, ISBN 8982732918, ISBN 8982732926, ISBN 8982732934, ISBN 898273287X (set) |

| Polish | Władca Pierścieni | 2001 | Books I – IV: Maria and Cezary Frąc; Book V: Aleksandra Januszewska; Book VI: Aleksandra Jagiełowicz; Poems: Tadeusz A. Olszański; Appendices: Ryszard Derdziński | Amber, Warszawa | ISBN 8372457018, ISBN 8324132872, ISBN 978-83-241-4424-2 |

| Slovenian | Gospodar prstanov | 2001 | Branko Gradišnik | Mladinska knjiga, Ljubljana | ISBN 8611162447, ISBN 8611163001, ISBN 861116301-X |

| Chinese (Simplified) | 魔戒 | 2001 | Book One – Book Two: Ding Di (丁棣); Book Three – Book Four: Yao Jing-rong (姚锦镕); Book Five – Book Six: Tang Ding-jiu (汤定九) | Yilin Press (译林出版社), Nanjing | ISBN 7-80657-267-8 |

| Chinese (Traditional) | 魔戒 | 2001 to 2002 | Lucifer Chu (朱學恆)[15] | Linking Publishing (聯經出版公司), Taipei | N/A |

| Galician | O Señor dos Aneis | 2001 to 2002 | Moisés R. Barcia | Xerais, Vigo | ISBN 84-8302-682-1 |

| Slovak | Pán prsteňov | 2001 to 2002 | Otakar Kořínek and Braňo Varsik | Vydavatelstvo Slovart, Bratislava | ISBN 8071456063, ISBN 8071456071, ISBN 807145608-X |

| Thai | ลอร์ดออฟเดอะริงส์ | 2001 to 2002 | Wanlee Shuenyong | Amarin, Bangkok | ISBN 974-7597-54-3 |

| Macedonian | Господарот на прстените Gospodarot na prstenite | 2002 | Romeo Širilov, Ofelija Kaviloska | AEA, Misla, Skopje | ISBN 9989-39-170-X, ISBN 9989-39-173-4, ISBN 9989-39-176-9 |

| Russian | Властелин колец Vlastelin kolec | 2002 | V. Volkovskij, V. Vosedov, D. Afinogenova | AST, Moscow | ISBN 5-17-016265-0 |

| Russian | Властелин Колец Vlastelin Kolec | 2002 | Alina V. Nemirova | AST, Kharkov | ISBN 5-17-009975-4, ISBN 5-17-008954-6, ISBN 966-03-1122-2 (Folio) |

| Basque | Eraztunen Jauna | 2002 to 2003 | Agustin Otsoa Eribeko | Txalaparta, Tafalla | ISBN 84-8136-258-1 |

| Indonesian | The Lord of the Rings | 2002 to 2003 | Anton Adiwiyoto, Gita K. Yuliani | Gramedia, Jakarta | ISBN 9796866935, ISBN 9792200355, ISBN 979220556-X |

| Latvian | Gredzenu Pavēlnieks | 2002 to 2004 | Ieva Kolmane | Jumava, Riga | ISBN 9984-05-579-5, ISBN 9984-05-626-0, ISBN 9984-05-861-1 |

| Persian | ارباب حلقهها Arbāb-e Halqehā | 2002 to 2004 | Riza Alizadih | Rawzanih, Tehran | ISBN 964-334-116-X, ISBN 964-334-139-9, ISBN 964-334-173-9 |

| Ukrainian | Володар Перснів Volodar Persniv | 2003 | Alina V. Nemirova[16] | Фоліо (Folio) | ISBN 966-03-1915-0 ISBN 966-03-1916-9 ISBN 966-03-1917-7 |

| Faroese | Ringanna Harri | 2003 to 2005 | Axel Tórgarð | Stiðin, Hoyvík | ISBN 99918-42-33-0, ISBN 99918-42-34-9, ISBN 99918-42-38-1 |

| Swedish | Ringarnas herre | 2004 to 2005 | Erik Andersson[17] and Lotta Olsson (poems) | Norstedts förlag | ISBN 91-1-301153-7 |

| Ukrainian | Володар Перстенів Volodar Persteniv | 2004 to 2005 | Olena Feshovets, Nazar Fedorak (poems) | Astrolabia, Lviv | ISBN 966-8657-18-7 |

| Albanian | Lordi i unazave, republished as Kryezoti i unazave | 2004 to 2006 | Ilir I. Baçi (part 1), Artan Miraka (2 and 3) | Dudaj, Tirana | ISBN 99927-50-96-0 ISBN 99943-33-11-9 ISBN 99943-33-58-5 |

| Norwegian (Nynorsk) | Ringdrotten | 2006 | Eilev Groven Myhren | Tiden Norsk Forlag, Oslo | ISBN 82-05-36559-8 |

| Arabic | سيد الخواتم، رفقة الخاتم، خروج الخاتم Sayyid al-Khawātim, Rafīqat al-Khātim, Khurūj al-Khātim | 2007 | Amr Khairy | Malamih, Cairo | ISBN 978-977-6262-03-4, only The Fellowship of the Ring, Book I |

| Belarusian | Уладар пярсьцёнкаў: Зьвяз пярсьцёнка, Дзьве вежы, Вяртаньне караля Uladar pyars'tsyonkaŭ: Z'vyaz Pyars'tsyonka, Dz've vezhy, Vyartan'ne karalya | 2008 to 2009 | Дзьмітрый Магілеўцаў and Крысьціна Курчанкова (Dźmitry Mahileŭcaŭ and Kryścina Kurčankova) | Mensk | Taraškievica orthography |

| Arabic | سيد الخواتم Sayyid al-Khawātim | 2009 | Farajallah Sayyid Muhammad | Nahdet Misr, Cairo | ISBN 977-14-4114-0, ISBN 977-14-1134-9, ISBN 977-14-1127-6 |

| Georgian | ბეჭდების მბრძანებელი: ბეჭდის საძმო, ორი ციხე–კოშკი, მეფის დაბრუნება Bech'debis Mbrdzanebeli: Bech'dis Sadzmo, Ori Tsikhe-k'oshki, Mepis Dabruneba | 2009 to 2011 | Nika Samushia (prose and poems) and Tsitso Khotsuashvili (poems in The Fellowship of the Ring) | Gia Karchkhadze Publishing, Tbilisi | ISBN 978-99940-34-04-8, ISBN 978-99940-34-13-0, ISBN 978-99940-34-14-7 |

| West Frisian | Master fan alle ringen | 2011 to 2016 | Liuwe Westra | Frysk en Frij and Elikser, Leeuwarden | ISBN 978-90-8566-022-4, ISBN 978-90-825871-0-4. Only Fellowship of the Ring and Two Towers translated so far |

| Ukrainian | Володар перснів Volodar persniv | 2013 | Kateryna Onishchuk-Mikhalitsyna, Nazar Fedorak (poems) | Astrolabia, Lviv | ISBN 978-617-664-022-6, ISBN 978-617-664-023-3, ISBN 978-617-664-024-0 |

| Chinese | 魔戒 | 2013 | 邓嘉宛 (story), 石中歌 (preface, prologue, appendix, and checking), 杜蕴慈 (poems) | Shanghai People's Publishing House (上海人民出版社) | ISBN 9787208113039 |

| Vietnamese | Chúa tể những chiếc Nhẫn | 2013 to 2014 | (Prose) Nguyễn Thị Thu Yến (f), Đặng Trần Việt (m); Tâm Thuỷ (f); (Poetry) An Lý (f) | Nhã Nam, Hanoi | N/A |

| French | Le Seigneur des anneaux | 2014 to 2016 | Daniel Lauzon | Christian Bourgois | ISBN 9782267027006 |

| Marathi | Swami Mudrikancha (I,II,III) | 2015 | Mugdha Karnik | Diamond Publications, Pune | ISBN 978-8184836219 |

| Yiddish | דער האַר פֿון די פֿינגערלעך Der Har fun di Fingerlekh | 2016 | Barry Goldstein | N/A | ISBN 978-1500410223, ISBN 978-1512129038, ISBN 978-1517654474 |

| Afrikaans | Die Heerser Van Die Ringe | 2018 to 2020 | Janie Oosthuysen | Protea Boekhuis, Pretoria | ISBN 978-1-4853-0975-8, ISBN 978-1-4853-0976-5, ISBN 978-1-4853-0977-2 |

| Azerbaijani | Üzüklərin Hökmdarı (I only) | 2020 | Qanun Nəşriyyatı | ISBN 978-9-9523-6832-1 |

See also

- Bibliography of J. R. R. Tolkien

- International reception of Tolkien

- Translations of The Hobbit

References

- Letters, 305f.; c.f. Martin Andersson "Lord of the Errors or, Who Really Killed the Witch-King?"

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). pp. 131–133. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Mark T. Hooker, "Dutch Samizdat: The Mensink-van Warmelo Translation of The Lord of the Rings," in Translating Tolkien: Text and Film, Walking Tree Publishers, 2004, pp. 83-92."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-02-16. Retrieved 2008-03-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Tolkien och den svarta magin (1982), ISBN 978-91-7574-053-9.

- Löfvendahl, Bo (30 December 2003). "Vattnadal byter namn i ny översättning". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- "Margaret Carroux". Ardapedia. Retrieved 2016-12-28.

- The second edition was therefore soon replaced the older one on the shelves, and it was published under the name: "שר הטבעות, תרגמה מאנגלית: רות לבנית. ערך מחדש: עמנואל לוטם ("The Lord of the Rings". Translated by Ruth Livnit, revised by Emanuel Lottem. Zmora Beitan [זמורה ביתן] publication: Tel Aviv, 1991)

- The new version, Editor's endnote.

- Yuvl Kfir, who assisted Dr. Lottem in the revision, wrote an article in favour of the new edition, translated by Mark Shulson: "Alas! The Aged and Good Translation!"

- FAQ Archived 2007-05-30 at the Wayback Machine at tolkien.co.uk

- Translations of The Hobbit

- a special edition of 1977 included illustrations by Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, working under the pseudonym of Ingahild Grathmer.

- The terminology was reworked and several mistakes corrected. For example, the original Hungarian translation left unclear whether Éowyn or Merry killed the Witch-king which caused confusion when the movie version was released.

- "COBISS/OPAC | Грешка". Vbs.rs. Retrieved 2013-06-19.

- Turning fantasy into a reality that helps others Gavin Phipps, Taipei Times, 6 March 2005, page 18.

- Unlicensed edition, translated from Alina Nemirova's Russian translation (2002, AST Publisher), in Maksym Strikha. Ukrainskyi khudozhniy pereklad: mizh literaturoyu i natsiyetvorennyam. Kyiv: Fakt, 2006. p. 305.

- published Översättarens anmärkningar "translator's notes" in 2007 (ISBN 978-91-1-301609-2)

Bibliography

- Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull, The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion (2005), ISBN 0-618-64267-6, 750-782.

- Allan Turner, Translating Tolkien: Philological Elements in "The Lord of the Rings," Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2005. ISBN 3-631-53517-1. Duisburger Arbeiten zur Sprach– und Kulturwissenschaft no. 59.

- Mark T. Hooker, Tolkien Through Russian Eyes, Walking Tree Publishers, 2003. ISBN 3-9521424-7-6.

.jpg)