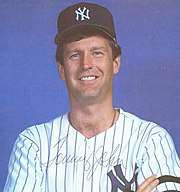

Tommy John

Thomas Edward John Jr. (born May 22, 1943) is an American retired professional baseball pitcher who played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for 26 seasons between 1963 and 1989. He played for the Cleveland Indians, Chicago White Sox, Los Angeles Dodgers, New York Yankees, California Angels, and Oakland Athletics. He was a four-time MLB All-Star.

| Tommy John | |||

|---|---|---|---|

John in 2008, attending a pre-All-Star game party in The Bronx | |||

| Pitcher | |||

| Born: May 22, 1943 Terre Haute, Indiana | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| September 6, 1963, for the Cleveland Indians | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| May 25, 1989, for the New York Yankees | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Win–loss record | 288–231 | ||

| Earned run average | 3.34 | ||

| Strikeouts | 2,245 | ||

| Teams | |||

| |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

John's 288 career victories rank as the seventh-highest total among left-handers in major league history. He had 188 career no decisions, an all-time MLB record among starting pitchers (dating back to at least 1908).[1] He is also known for the surgical procedure ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction, nicknamed "Tommy John surgery", which he underwent in 1974 after damaging the ligament in his throwing arm.[2] John was the first pitcher to receive the operation, and despite a poor outlook initially, he returned to being an effective pitcher, as more than half of his career wins came after his surgery. It has since become a common procedure among baseball pitchers.

Early life

John grew up in Terre Haute, Indiana. As a youth, he often played sandlot ball with other kids, either at Spencer Field or Woodrow Wilson field.[3] Arley Andrews, a former minor league pitcher and a friend of John's dad, taught John to throw a curveball, which would be John's main pitch. John was an outstanding baseball and basketball player at Gerstmeyer High School in Terre Haute, Indiana. He had a 28-2 record as a pitcher[4] and held the city single-game scoring record on the basketball team. All the athletics did not get in the way of his schoolwork, as John graduated as Gerstmeyer's 1961 valedictorian. He did not deliver a speech at commencement due to a stuttering problem he had at the time.[5] Several colleges recruited John to play basketball for them, including University of Kentucky, but John also caught the eye of Cleveland Indians' scout Johnny Schulte, who worried that John needed more of a fastball to succeed but considered his curveball already a major league pitch. John picked baseball and signed with the Indians after graduating, getting assigned to the Dubuque Packers of the Class D Midwest League.[4][6]

Playing career

John had a 10-4 record in 1961 but had some trouble with the Charleston Indians of the Class A Eastern League in 1962. "I was rearing back on every pitch and firing with all my strength at the strike zone,” he said. “As a result I kept getting behind in the ball-and-strike count, often running it to three balls and no strikes, so I just had to put my fastball right over the plate and get it creamed."[4] This led to a lot of walks, but player-coach Steve Jankowski worked with him, suggesting that John throw less hard so that he would have more control. The alterations helped John get called up to the Class AAA Jacksonville Suns of the International League during the year, and John won two games for them with the playoffs. He started 1963 with Jacksonville, got sent down to Charleston, went 9-2 with a 1.61 ERA for the West Virginian Indians, and got called up to the major leagues in September at the age of twenty.[4]

September 6, 1963, started the long major league career of Tommy John, who allowed one unearned run in one inning of a 7-2 loss to the Washington Senators.[7] Used at first as a reliever, he finished the year with three starts.[8] Though his record was 0-2, his earned run average (ERA) was 2.21. Manager Birdie Tebbetts called his fastball "deceptive."[4]

In his first start of 1964, on May 3, John threw a shutout against the Baltimore Orioles for his first major league win in the second game of a doubleheader.[9] He won two of his first three games but then lost eight decisions in a row and got sent to AAA (now the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League) in July.[10] Indians' pitching coach Early Wynn had been trying to get John to throw a slider, but John altered his grip, affecting his control.[4] He returned to throwing just a fastball and a curveball in the minors and was called up for a few games in September by the Indians.[4][10] After the season, he was sent to the Chicago White Sox as part of a three-way trade between Cleveland, Chicago, and the Kansas City Athletics that sent Rocky Colavito to Cleveland.[4]

John's first appearances with the White Sox were in relief. During the first half of the 1965 season, he and Juan Pizarro alternatively spent time as Chicago's fifth starter in the rotation.[11] By the second half, however, he had cemented himself within the team's starting rotation.[12] September 25, he held the New York Yankees to one run and hit a go-ahead home run against Bill Stafford to give himself a 3-1 victory.[13] In 39 games (27 starts), he had a 14-7 record, a 3.09 ERA, 126 strikeouts, 58 walks, and 162 hits allowed in 183 2⁄3 innings.[14]

By 1966, manager Eddie Stanky had made John his Opening Day starter.[15] He tied for the American League (AL) lead with five shutouts during the season.[14] Two of these, May 7 against the Detroit Tigers and August 12 against the California Angels, came on days when the White Sox only scored one run for him.[15] In 34 games (33 starts), he had a 14-11 record, a 2.62 ERA, 138 strikeouts, 57 walks, and 195 hits in 223 innings.[14] His 2.62 ERA placed fifth in the league, and his 10 complete games tied for ninth (with Mudcat Grant).[16]

Once again in 1967, John led the AL in shutouts, this time with six. He had a season-high nine strikeouts in a shutout of the Senators on June 13.[17][18] On July 4, he shut out the defending-World Series champion Orioles, limiting Baltimore to two hits.[19] July 22, he left a game against the Athletics after facing just two batters and did not pitch again until August 20.[17] At season's end, his record was just 10-13, but his 2.47 ERA ranked fourth in the league.[14][20] He had 110 strikeouts, 47 walks, and 143 hits allowed in 178 1⁄3 innings.[14]

1968 started out as John's best season thus far in his career. On June 30, he shut out the Tigers in a 12-0 victory.[21] With a 1.78 ERA in the first half, he was named to the All-Star Game for the first time in his career.[14][22] Another highlight came against Cleveland August 9, when he held the Indians scoreless for seven innings and scored the only run of the game.[23] He had a 1.98 ERA through 25 starts with the White Sox in 1968.[22] August 22 of that year, with a 3-2 count on Dick McAuliffe, John threw ball four over McAuliffe's head. An angry McAuliffe charged the mound and started a fight between the two players. McAuliffe was fined and suspended; John was not punished, but he tore some shoulder ligaments in the scuffle and missed the rest of the season with an injury.[24] Thirty years later, McAuliffe said in an interview that he still thought John was trying to hit him in that game.[25] White Sox' general manager Ed Short noted that this was unlikely given that the pitch before the fight came on a 3-2 count, resulting in a walk for McAuliffe.[24] Though pitcher ERAs were down across baseball in 1968,[26] John's still ranked fifth in the league.[27] He had a 10-5 record and gave up just 135 hits in 177 1⁄3 innings.[14]

Johnny Sain became the White Sox' pitching coach in 1971, and he was determined to change John's pitching mechanics.[4][28] This caused trouble for John, who had his highest ERA since 1964.[14][4] Through his first 11 games, his ERA was 6.08, but he posted a 2.97 ERA in his last 27 games.[29] In the first game of a doubleheader against the defending World Champion Orioles on May 31, he threw a shutout in a 1–0 victory.[30] On June 17, he held the Twins to three runs over 10 innings. The White Sox pinch-hit for him in the 11th, took a 6–3 lead, then lost 7–6 after three relievers gave up four runs in the bottom of the inning.[31] He struck out a season-high nine hitters on June 29 but also gave up four runs (two earned) in a 5–2 loss to the Milwaukee Brewers.[29] In 38 games (35 starts), he had a 13–16 record, a 3.61 ERA, three shutouts, 131 strikeouts, 58 walks, and 244 hits in 229 1⁄3 innings pitched.[14] His 16 losses tied him for seventh in the AL with Ray Culp and Dick Bosman.[32]

However, it was a trade before the 1972 season to the Los Angeles Dodgers for mercurial slugger Dick Allen that began a skein of John's most famous years, first with the Dodgers and subsequently with the New York Yankees, where he posted a pair of 20-win seasons and was twice an All-Star. John was also named an All-Star in 1968 with the White Sox and 1978 with LA. He played in all three Yankees vs. Dodgers World Series of his era (1977, 1978 and 1981), having switched over to the Yankees by the time the Dodgers won the Series in 1981.

In the middle of an excellent 1974 season, John had a 13–3 record as the Dodgers were en route to their first National League pennant in eight years. He led the NL in wins coming into the All-Star break but was left off the roster, as the Dodgers already had Andy Messersmith and Mike Marshall on the team. "If I don't belong on the team, there is no justice in baseball," John said. "It really sets you back. I've had a great year, I've worked hard and yet I can't even get picked for the All-Star team."[33] Bigger disappointment was to follow, as shortly thereafter, he permanently damaged the ulnar collateral ligament in his pitching arm, leading to a revolutionary surgical operation. This operation, now known as Tommy John surgery, replaced the ligament in the elbow of his pitching arm with a tendon from his right forearm. The surgery was performed by Dr. Frank Jobe on September 25, 1974, and it seemed unlikely he would ever be able to pitch again. Jobe gave the operation 100-1 odds of being successful, but John had it anyway, as his other option was to start working at a friend's car dealership in Terre Haute. He spent the entire 1975 season in recovery. John worked with teammate and pitcher Mike Marshall, who had a Ph.D. in kinesiology and who was said to know how to help pitchers recover from injuries, on learning a different grip to use while pitching.[34]

John returned to the Dodgers in 1976. His 10–10 record that year was considered "miraculous", and he followed in 1977 with his first career 20-win season, going 20-7 with a 2.78 ERA as the Dodgers won the National League West, the NL pennant, and reached the 1977 World Series. John was dissatisfied with his contract entering spring training in 1977 and threatened to file for free agency after the season, but he stayed with Los Angeles through 1978.[35] He helped the Dodgers return to the World Series in 1978 with a 17-10 record before leaving for the New York Yankees as a free agent. By July 7, 1979, he was leading the AL in wins and had a 13-3 record, as he had five years earlier with the Dodgers, before the surgery.[36] With the Yankees, John posted 20-win seasons in 1979 and 1980; no other AL pitcher would win 20 games in back-to-back years until Roger Clemens did it in 1986 and '87.[37] He pitched particularly well against the White Sox in 1980, throwing shutouts all three times he faced them.[38] He helped the Yankees win the AL pennant in 1981. In the World Series, with the Yankees down to the Dodgers 3 games to 2, John started Game 6. He held the Dodgers to one run over four innings but was pinch-hit for by Bobby Murcer in the fourth. "I was trying to get a run ahead so I could get to the seventh inning and bring Goose in," explained Yankee manager Bob Lemon.[39] The Yankees failed to score that inning, and the relievers did not pitch well, enabling the Dodgers to win the game and the series. Will Grimsley of the Associated Press called the decision to pull John "a glaring error."[39]

The Yankees and John nearly went to arbitration after 1981 but ultimately agreed to a two-year, $1.7 million contract. "I'm glad to get it over with and get it put to bed," John said after signing. "It's like in a marriage. If you have an argument and patch it up fast, it's okay. But the longer you let it go, the harder it is to reconcile it."[40]

John went unsigned to begin 1986, and it looked like his career might be over. Injuries to Ed Whitson and John Montefusco in May caused the Yankees to re-sign their former pitcher.[41] That year, rookie Mark McGwire had two hits off him;[42] McGwire's father was John's dentist. John said of this, "When your dentist's kid starts hitting you, it's time to retire!"[43] Tommy John went on to pitch three more seasons.[14] He had a 9-8 record in 1988, with a 4.49 ERA, 81 strikeouts, 46 walks, and 221 hits allowed in 176 1⁄3 innings. Bill Madden of the New York Daily News speculated that John, a ground-ball pitcher, suffered from late-season injuries to Yankee infielders Willie Randolph and Mike Pagliarulo, their replacements not being quite as capable fielders. Ten times, he left a game after at least five innings with a lead and received a no-decision, often due to runners he had left on base scoring when relievers replaced him. At 45, he was the only Yankee starter to go the full year without missing time due to injury.[44]

John went on to pitch until 1989, winning 164 games after his surgery—forty more than before. After Phil Niekro's retirement, John spent 1988 and 1989 as the oldest player in the major leagues. By 1989, he was doing a "ten-part cardiovascular and muscular endurance program" which Jeff Mangold, the Yankees' former strength coach, had helped him develop.[44] In 1989, John matched Deacon McGuire's record for most seasons played in a Major League Baseball career with 26, later broken by Nolan Ryan.[45] April 27, he held the Royals to two runs over eight-plus innings, picking up his 288th (and final) victory.[46]

In 2009, in his 15th and final year of eligibility for election into the Baseball Hall of Fame, John received only 31.7% of the vote.[47] He needed at least 75% in order to be elected. He could still enter the Hall if he were selected by the Veterans Committee. On the edition of June 22, 2012 of The Dan Patrick Show, Patrick and longtime baseball commentator Bob Costas discussed the impact that Tommy John surgery has had on the game, stating that there could be a case for John being awarded the Buck O'Neil Lifetime Achievement Award.

John was inducted into the Baseball Reliquary's Shrine of the Eternals in 2018.[48]

John was announced as one of the finalists for the 2020 Modern Baseball Era ballot, however he was not elected when inductees were announced on December 8, 2019.

Pitching style

John was a soft throwing sinkerball pitcher whose technique resulted in batters hitting numerous ground balls and induced double plays.[34] At the start of his major league career, he threw just a fastball and a curveball. The Indians tried to get him to throw a slider in 1964, but John struggled with it and went back to throwing two pitches later that year.[4] In 1972, he added a screwball, which he used as a changeup to complement his repertoire.[49] His arm lagged behind the rest of his body when he threw pitches, a technique that put extra stress on it, which contributed to his UCL injury in 1974.[34]

Post-retirement

John served as the color commentator for the Charlotte Knights of the International League in 1997.[50] In 1998, he did commentary on select games during WPIX's final year of broadcasting Yankee baseball. In the edition of June 24, 1985 of ABC's Monday Night Baseball, John served as color commentator alongside Tim McCarver for a game between the Chicago White Sox and Oakland Athletics. He also guest-hosted the Mike and Mike ESPN Radio program on June 26, 2008. It is unknown if he will continue any similar work for the network in the future. On December 17, 2006, John was named manager of the Bridgeport Bluefish in the Atlantic League, an independent minor league in the Northeast. Tommy John resigned as manager of the Bridgeport Bluefish on July 8, 2009, to pursue a "non-baseball position" with Sportable Scoreboards.[51] In two-and-a-half years of managing, he compiled a 159–176 won-lost record with Bridgeport.

In 2012, he was the spokesman for Tommy John's Go-Flex, a joint cream for older athletes and doing a national radio tour to promote this product as well as talk about life as a minor league coach, his years in the Major Leagues and to educate younger pitchers on the importance of taking care care of their arms.[52] In 2013 the initial Tommy John surgery, John's subsequent return to pitching success, and his relationship with orthopedic surgeon Dr. Frank Jobe, who developed the procedure, was the subject of an ESPN 30 for 30 Shorts documentary.[53]

Personal life

Tommy married the former Sally Simmons on July 13, 1970. They are the parents of four children: Tamara, Tommy III, Travis, and Taylor. In 1981, when Travis was two years old, he fell 37 feet from a third-floor window in his family's New Jersey vacation house, bounced off the fender of a car and then lay in a coma for 17 days.[54] President Ronald Reagan sent Travis a get-well card.[55] He later made a full recovery.[54] On March 9, 2010, Taylor John, age 28, died as the result of a seizure and heart failure apparently due to an overdose of prescription drugs.[56] As a 10-year-old in 1992, Taylor's singing and acting talents had landed him a role in Les Misérables on Broadway. He took time off from the stage, however, to play baseball at Federal Little League in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.[57]

In 1998, Tamara John married Chicago Bears long snapper Patrick Mannelly.[58] Tommy's oldest son, Tommy John III, was an All-Southern Conference designated hitter for the Furman University Paladins in 1999; he later spent two seasons in the independent minor leagues as a pitcher for the Tyler Roughnecks and Schaumburg Flyers.[59] Tommy III was a 4-year letterman for the Paladins, leading the team in complete games as pitcher in 1997 (3 games), in home runs (9) in 1999 and is one of three Furman players in 113 years of varsity baseball to hit for the cycle, doing so on April 1, 2000 vs the Appalachian State Mountaineers.[60]

In 1979, John's collegiate alma mater Indiana State University, named him a Distinguished Alumnus.[61]

On October 24, 2013, the Terre Haute, Indiana, Parks Department honored John with the dedication of a baseball diamond at the Spencer F. Ball Park baseball complex where John's last non-professional game was played in 1961, as a member of the Terre Haute Gerstmeyer High School Black Cats.[3][62]

Bibliography

- The Tommy John Story, F.H. Revell Company, 1978. ISBN 0-8007-0923-3. (With Sally John and Joe Musser, foreword by Tommy Lasorda.)

- The Sally and Tommy John Story: Our Life in Baseball, Macmillan, 1983. ISBN 0-02-559260-2. (With Sally John.)

- TJ: My Twenty-Six Years in Baseball, Bantam, 1991. ISBN 0-553-07184-X. (With Dan Valenti.)

See also

References

- "Pitching Game Finder: From 1908 to 2018, Recorded no decision, as Starter, sorted by greatest number of games in all seasons matching the selected criteria". Baseball Reference. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- Purcell DB, Matava MJ, Wright RW (2007). "Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: a systematic review". Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 455: 72–77. doi:10.1097/BLO.0b013e31802eb447. PMID 17279038.

- Mark Bennett (October 24, 2013). "Tommy John's Field of Dreams". Tribstar.com. Terre Haute Tribune Star: Columns. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- Fallon, Michael. "Tommy John". SABR. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- LoPresti, Mike (May 29, 2014). "LoPresti: Legacy of Terre Haute's Tommy John goes beyond the surgery". IBJ. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- "Tommy John Minor & Independent League Stats". Baseball-Reference (Minors). Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- "Cleveland Indians at Washington Senators Box Score, September 6, 1963". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- "Tommy John 1963 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- "Cleveland Indians at Baltimore Orioles Box Score, May 3, 1964". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Tommy John 1964 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "1965 Chicago White Sox Pitching Game Log". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Tommy John 1965 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Chicago White Sox at New York Yankees Box Score, September 25, 1965". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- "Tommy John Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- "Tommy John 1966 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- "1966 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- "Tommy John 1967 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "Chicago White Sox at Washington Senators Box Score, June 13, 1967". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "Baltimore Orioles at Chicago White Sox Box Score, July 4, 1967". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "1967 AL Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "Chicago White Sox at Detroit Tigers Box Score, June 30, 1968". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- "Tommy John 1968 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- "Cleveland Indians at Chicago White Sox Box Score, August 9, 1968". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- Associated Press (August 24, 1968). "McAuliffe Suspended, John Hurt, Regan Snickering". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Cizik, John. "The Baseball Biography Project: Dick McAuliffe". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- Rushin, Steve (July 19, 1993). "The Season Of High Heat". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 25, 2011.

- "1968 AL Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Zminda, Don. "Working Overtime: Wilbur Wood, Johnny Sain and the White Sox Two-Days' Rest Experiment of the 1970s". SABR. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- "Tommy John 1971 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- "Baltimore Orioles at Chicago White Sox Box Score, May 31, 1971". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- "Chicago White Sox at Minnesota Twins Box Score, June 17, 1971". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- "1971 AL Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- Associated Press (July 18, 1974). "National League". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Berra, Lindsay (March 20, 2012). "The problem with Tommy John surgery". ESPN. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- Associated Press (March 1, 1977). "Royster concentrates on more base thefts". Rome News-Tribune. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Associated Press (July 7, 1979). "Drago, Horton brawl protagonists". Lawrence Journal-World. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Associated Press (October 5, 1987). "Tanana Pitches Tigers to Title". Moscow-Pullman Daily News. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- "Tommy John 1980 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Associated Press (October 29, 1981). "Lemon defends move". Gadsden Times. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- "Sports of all sorts". Beaver County Times. February 15, 1982. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- "Rangers' Correa, 20, has dream come true". The Pittsburgh Press. May 3, 1986. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- "Mark McGwire vs. Tommy John | Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- Simon, Scott (August 28, 2010). "Stephen Strasburg, Meet Tommy John". Npr.org. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- Madden, Bill (January 30, 1989). "Tommy John looking for one last hurrah". Allegheny Times. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Michael X. Ferraro and John Veneziano (2007). Numbelivable! Chicago: Triumph Books, p. 157. ISBN 978-1-57243-990-0

- Associated Press (April 28, 1989). "Yankees 3, Royals 2". Gainesville Sun. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Sklar, Debbie L. (December 11, 2017). "Steve Garvey, Tommy John rejected in baseball Hall of Fame bids". mynewsla.com. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- "Shrine of the Eternals – Inductees". Baseball Reliquary. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- "Dodgers' Winter Deals Look Better and Better". Kingsport Post. May 11, 1972. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Fulkerson, Vickie (May 20, 1997). "Her love of sailing second only to love of teaching it". The Day. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- "Tommy John Steps Down as Bluefish Manager". Bridgeportbluefish.com. July 8, 2009. Archived from the original on January 4, 2010. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- "Official Site of the Bridgeport Bluefish". Bridgeportbluefish.com. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- Grantland staff (July 23, 2013). "30 for 30 Shorts: Tommy and Frank". Grantland. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- Sandomir, Richard (October 25, 1996). "John Family Recalls New York's Support". The New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- "'CHiPs' star hurt in cycle accident". Eugene Register-Guard. August 28, 1981. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- Jensen, Trevor (March 10, 2010). "Taylor John, 1981–2010: Son of baseball great Tommy John". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015.

- Archived April 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Weddings; Tamara John, James Mannelly". The New York Times. June 21, 1998.

- "Tommy John Register Statistics & History". Baseball-Reference.com. August 31, 1977. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- "Furman University – 2013 Furman Baseball Yearbook". Catalog.e-digitaleditions.com. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- Archived February 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Foulkes, Arthur. "Diamond to be named for Tommy John". Tribstar.com. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball-Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Tommy John at SABR (Baseball BioProject)

- Tommy John This Day in Baseball Page

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Davey Johnson |

National League Player of the Month April 1974 |

Succeeded by Ralph Garr |