Timeline of the history of the scientific method

This timeline of the history of the scientific method shows an overview of the development of the scientific method up to the present time. For a detailed account, see History of the scientific method.

BC

Nineteenth-century illustation of the ancient Great Library at Alexandria

- c.1600 BC — The Edwin Smith Papyrus, a unique ancient Egyptian text, contains practical and objective advice to physicians regarding the examination, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis, of injuries and ailments.[1] It provides evidence that medicine in Egypt was at this time practised as a quantifiable science.[2]

- 624 - 548 BC — Thales of Miletus raises the study of nature from the realm of the mythical to the level of empirical study.[3]

- 610 - 547 BC — The Greek philosopher Anaximander extends the idea of law from human society to the physical world, and is the first to use maps and models.[4]

- c.400 BC — In China, the philosopher Mozi (Chinese: 墨翟) founds the Mohist school of philosophy (Chinese: 墨家) and introduces the 'three-prong method' for testing the truth or falsehood of statements.[5]

- c.400 BC — The Greek philosopher Democritus advocates inductive reasoning through a process of examining the causes of perceptions and drawing conclusions about the outside world.[6]

- c.400 BC — Plato first provides detailed definitions of the concepts of idea, matter, form and appearance as abstract concepts.

- c.320 BC — Aristotle categorises and subdivides knowledge, dividing it into different areas—physics, poetry, zoology, logic, rhetoric, politics, and biology. His Posterior Analytics defended the ideal of science as originating from known axioms. Aristotle believed that the world was real and that we can learn the truth by experience.[7]

- c.341-270 BC — Epicurus and his followers develop an epistemology as a result of their rivalry with other philosophical schools. His treatise Κανών ('Rule'), now lost, explained his methods of investigation and theory of knowledge.[7][8]

- c.300 BC — Euclid's Euclid's Elements expounds geometry as a system of theorems following logically from axioms.

- c.240 BC — The Greek polymath Eratosthenes calculates the circumference of the Earth to a remarkable degree of accuracy, using stadia, then a standard unit for measuring distances.

- c.200 BC — The Great Library of Alexandria is built as part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, with the intention that it becomes a collection of all Greek knowledge.[9]

- c.150 BC — The first chapter of the Book of Daniel describes an early (and flawed) version of a clinical trial proposed by the young Jewish noble Daniel, in which he and his three companions eat vegetables and water for ten days, rather than the royal food and wine.[10]

1st–12th centuries

Drawing and description of an alembic, by Jabir ibn Hayyan, popularly known as the father of chemistry

- c.90-168 — Ptolemy writes the astronomical treatise now known as the Almagest. His writings reveal his understanding of the scientific method, his recognition of the importance of both systematically ordered observations and hypotheses.[11]

- c.721-873 — Muslim scientists uses experiment and quantification to distinguish between competing scientific theories, set within a generically empirical orientation, as can be seen in the works of Jābir ibn Hayyān (721–815)[12] and Alkindus (801–873).[13]

- 1021 — The astronomer, physicist and mathematician Ibn al-Haytham introduces the experimental method and combines observations, experiments and rational arguments in his Book of Optics.

- c.1025 — The scholar Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī develops experimental methods for mineralogy and mechanics, and conducts elaborate experiments related to astronomical phenomena.

- 1027 — In his treatise al-Burhân ('On Demonstration') in his book Kitāb al-Šifāʾ ('The Book of Healing'), the Persian polymath Ibn Sīnā (known in the Western world as Avicenna) censures Aristotelian method of induction.[14]

1200–1700

- 1220–1235 — Robert Grosseteste, an English scholastic philosopher, theologian and later the Bishop of Lincoln during 1253, publishes his Aristotelian commentaries, laying out the framework for the proper methods of science.[15]

- 1265 — The English monk Roger Bacon, inspired by the writings of Robert Grosseteste, describes a scientific method based on a repeating cycle of observation, hypothesis, experimentation, and the need for independent verification. He recorded the manner in which he conducted his experiments in precise detail so that others could reproduce and independently test his results.[16][17]

- 1327 — Ockham's razor appears, a principle which states that among competing hypotheses, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected.

- 1408 — The Yongle Encyclopedia (Chinese: 永樂大典), the largest encyclopedia in book form every made, is completed.

- 1581 — The sceptic Francisco Sanches uses classical sceptical arguments to show that science, in the Aristotelian sense of giving necessary reasons or causes for the behavior of nature, cannot be attained.

- 1581 — The Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe builds Uraniborg and Stjerneborg on the island of Ven. Research done in the fields of astronomy, alchemy, and meteorology by Tycho and his assistants produces high precision measurements of the planets.

- 1595 — The microscope is invented in the Netherlands.

- 1608 — Evidence of the earliest known telescope appears in the Netherlands, when a patent is submitted by Hans Lipperhey.[18]

- 1609 — The first 'public chemical laboratory' is set up at the University of Marburg.[19]

- 1620 — The Novum Organum, fully Novum Organum, sive indicia vera de Interpretatione Naturae ("New Organon, or true directions concerning the interpretation of nature"), a philosophical work by English philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon, is published.

- 1637 — The French philosopher, mathematician and scientist René Descartes publishes his Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences, an important work in the development of the natural sciences.[20]

- 1638 — Galileo's Discorsi e dimostrazioni matematiche intorno a due nuove scienze (commonly known as Two New Sciences), his scientific testament covering much of his work in physics over the preceding thirty years, is published. It contains two thought experiments, now referred to as his Leaning Tower of Pisa experiment and Galileo's ship, each invented to disprove a physical theory by showing that it has a contradictory consequence.

Robert Boyle's notebook for 1690-1. Boyle was a founding Fellow of the Royal Society.

- 1650 — The world's oldest national scientific institution, the Royal Society, is founded in London. It establishes experimental evidence as the arbiter of truth.

- c.1665 — The British scientist Robert Boyle reveals his scientific methods in his writings, and commends that a subject be generally researched before detailed experiments are undertaken; that results that are inconsistent with current theories are reported; that experiments should be regarded as 'provisional' in nature; and that experiments are shown to be repeatable.[21]

- 1665 — Academic journals are published for the first time, in France and Great Britain.[22]

- 1675 — To encourage the publicising of new discoveries in science, the German-born Henry Oldenburg pioneers the practice now known as peer reviewing, by sending scientific manuscripts to experts to judge their quality.[23]

- 1687 — Sir Isaac Newton's book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), is first published. It laid the foundations of classical mechanics. Newton also made seminal contributions to optics, and shares credit with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz for developing the infinitesimal calculus.

1700–1900

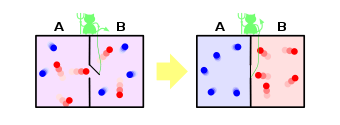

A schematic diagram of Maxwell's demon (1867), a thought experiment involving an imaginary process sorting out particles according to their speed

- 1739 — David Hume's Treatise of Human Nature argues that the problem of induction is unsolvable.

- 1753 — The first description of a controlled experiment using identical populations with only one variable is published, when James Lind, a Scottish doctor, undergoes research into scurvy among sailors.[24]

- 1763 — Reverend Thomas Bayes' An Essay towards solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances is published posthumously. The Essay laid the basis for Bayesian inference, used to update the probability estimate for a hypothesis as additional evidence is acquired.

- 1812 — Hans Christian Ørsted formulates the Latin-German mixed term Gedankenexperiment, or thought experiment, a method used since antiquity.

- 1815 — An optimal design for polynomial regression is published by the French logician Joseph Diaz Gergonne.

- 1833, 1840 - William Whewell invents the term scientist, previously 'natural philosopher' or 'man of science'. In his Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences he coins the term "consilience" the principle that evidence from independent, unrelated sources can 'converge' to strong conclusions.

- 1877–1878 — The American scientist Charles Sanders Peirce writes his Illustrations of the Logic of Science. The work popularises his trichotomy of abduction, deduction and induction.

- 1885 — Peirce and Joseph Jastrow first describe blinded, randomized experiments.[25]

- 1897 — The American geologist Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin proposes the use of multiple hypotheses to assist in the design of experiments.

1900–present

- 1905 — The German-born theoretical physicist Albert Einstein proposes the theory of special relativity.

- 1926 — Randomized design is popularized and analyzed by the British statistician Ronald Fisher.

- 1934 — Falsifiability as a criterion for evaluating new hypotheses is popularized by Karl Popper's The Logic of Scientific Discovery .

- 1937 — The first complete placebo trial is undertaken. The American pharmacologist Harry Gold, studying the effect of xanthines on cardiac pain, alternates them with a placebo and shows them to be ineffective.[26]

- 1946 — Work begins on the first computer simulation in history, a digital flight simulator developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for training bomber crews.[27]

- 1950 — Research based on the double blind test is published for the first time, by Greiner et al.[28]

- 1962 — The American physicist Thomas S. Kuhn publishes his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, which controversially challenged powerful and entrenched philosophical assumptions about the progress of science through history.[29]

- 1964 — Strong inference—a model of scientific inquiry that emphasizes the need for alternative hypotheses—is proposed by the American physicist John R. Platt.[30]

- 2009 — Robot Scientist (also known as Adam) is created, the first machine in history to have discovered new scientific knowledge independently of its human creators.[31]

- 2012 — Constructor theory, a proposal for a new mode of explanation in fundamental physics, is sketched out by the British physicist David Deutsch.[32]

References

- Edwin Smith papyrus, Encyclopædia Britannica

- Allen 2005, p. 70.

- Magill 2003, p. 1121.

- Magill 2003, p. 70.

- Burgin 2017, p. 431.

- Berryman, Sylvia (2016). "Democritus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Gauch, Hugh G. (2003). Scientific Method in Practice. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521017084. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- Asmis 1984, p. 9.

- König, Oikonomopoulou & Woolf 2013, p. 96.

- Neuhauser, D.; Diaz, M. "Daniel: using the Bible to teach quality improvement methods" (PDF). BMJ. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Kattsoff, Louis O. (1947). "Ptolemy and Scientific Method: A Note on the History of an Idea". Isis. 38 (1): 18–22. doi:10.1086/348030. JSTOR 225444.

- Holmyard, E. J. (1931), Makers of Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 56

- Plinio Prioreschi, "Al-Kindi, A Precursor Of The Scientific Revolution", Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine, 2002 (2): 17–19 [17].

- McGinnis, Jon (2003). "Scientific Methodologies in Medieval Islam". Journal of the History of Philosophy. 41 (3): 307–327. doi:10.1353/hph.2003.0033. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Ireland, Maynooth James McEvoy Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy National University of (31 August 2000). Robert Grosseteste. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195354171. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Clegg 2013.

- Hackett, Jeremiah (2013). "Roger Bacon". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Van Helden et al. 2010, p. 4.

- Morris, Peter J. T. (2015). "How Did Laboratories Begin?". The Matter Factory: A History of the Chemistry Laboratory. London: Reaktion Books Ltd. ISBN 9781780234748.

- Wilson, Fred. "René Descartes: Scientific Method". Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Bishop, D.; Gill, E. (2020). "Robert Boyle on the importance of reporting and replicating experiments". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 113 (2): 79–83. doi:10.1177/0141076820902625. PMID 32031485. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Banks, David (2017). The Birth of the Academic Article: Le Journal Des Sçavans and the Philosophical Transactions, 1665-1700. ISBN 9781781792322. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Committee on the Conduct of Science 1995, pp. 9-10.

- James Lind's A Treatise of the Scurvy

- Charles Sanders Peirce and Joseph Jastrow (1885). "On Small Differences in Sensation". Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences. 3: 73–83.

See also:

- Hacking, Ian (September 1988). "Telepathy: Origins of Randomization in Experimental Design". Isis. 79 (3: A Special Issue on Artifact and Experiment): 427–451. doi:10.1086/354775. JSTOR 234674. MR 1013489.

- Stephen M. Stigler (November 1992). "A Historical View of Statistical Concepts in Psychology and Educational Research". American Journal of Education. 101 (1): 60–70. doi:10.1086/444032.

- Trudy Dehue (December 1997). "Deception, Efficiency, and Random Groups: Psychology and the Gradual Origination of the Random Group Design" (PDF). Isis. 88 (4): 653–673. doi:10.1086/383850. PMID 9519574.

- Shorter, Edward (2011). "A Brief History of Placebos and Clinical Trials in Psychiatry". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 56 (4): 193–197. doi:10.1177/070674371105600402. PMC 3714297. PMID 21507275.

- "1946". Timeline of Computer History. Computer History Museum. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Shapiro & Shapiro 1997, pp. 146-148.

- Naughton, John (19 August 2012). "Thomas Kuhn: the man who changed the way the world looked at science". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Platt, John R. (16 October 1964). "Strong inference. Certain systematic methods of scientific thinking may produce much more rapid progress than others". Science. 146 (3642): 347–353. doi:10.1126/science.146.3642.347. PMID 17739513.

- Liakata, Maria; Soldatova, Larisa; et al. (2000). "The Robot Scientist 'Adam'". Academia. Computer. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Heaven, Douglas. "Theory of everything says universe is a transformer". New Scientist. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

Sources

- Allen, James P. (2005). The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 1-58839-170-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Asmis, Elizabeth (1984), Epicurus' Scientific Method, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-08014-1465-7CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)(registration required)

- Burgin, Mark (2017). Theory Of Knowledge: Structures And Processes. New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. ISBN 97898-145226-70.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clegg, Brian (2013). Roger Bacon: The First Scientist. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 9781472112125.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)(registration required)

- Committee on the Conduct of Science (1995). On being a scientist: responsible conduct in research. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)(registration required)

- König, Jason; Oikonomopoulou, Katerina; Woolf, Greg, eds. (2013). Ancient Libraries. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01256-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Magill, Frank N. (16 December 2003). The Ancient World: Dictionary of World Biography. Routledge. ISBN 9781135457396. Retrieved 9 March 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shapiro, Arthur K.; Shapiro, Elaine (1997). The Powerful Placebo: From Ancient Priest to Modern Physician. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6675-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Helden, Albert; Dupre, Sven; van Gent, Rob; Zuidervaart, Huib, eds. (2010). The Origins of the Telescope. Amsterdam: KNAW Press. ISBN 978-90-6984-615-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.