Thylacosmilus

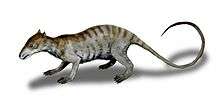

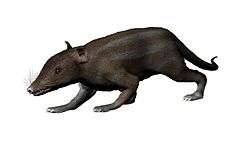

Thylacosmilus is an extinct genus of saber-toothed metatherian mammals that inhabited South America from the Late Miocene to Pliocene epochs. Though Thylacosmilus looks similar to the "saber-toothed cats", it was not a felid, like the well-known North American Smilodon, but a sparassodont, a group closely related to marsupials, and only superficially resembled other saber-toothed mammals due to convergent evolution. A 2005 study found that the bite forces of Thylacosmilus and Smilodon were low, which indicates the killing-techniques of saber-toothed animals differed from those of extant species. Remains of Thylacosmilus have been found primarily in Catamarca, Entre Ríos, and La Pampa Provinces in northern Argentina.[1]

| Thylacosmilus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Two reconstructed skeletons mounted in fighting pose, Museum of Paleontology Egidio Feruglio | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Sparassodonta |

| Family: | †Thylacosmilidae |

| Genus: | †Thylacosmilus Riggs 1933 |

| Species: | †T. atrox |

| Binomial name | |

| †Thylacosmilus atrox Riggs 1933 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

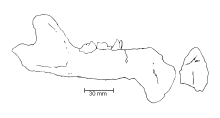

In 1926, the Marshall Field Paleontological Expeditions collected mammal fossils from the Ituzaingó Formation of Corral Quemado, in Catamarca Province, northern Argentina. Three specimens were recognized as representing a new type of marsupial, related to the borhyaenids, and were reported to the Paleontological Society of America in 1928, though without being named. In 1933, the American paleontologist Elmer S. Riggs named and preliminarily described a new genus based on these specimens, while noting that a full description was being prepared and would be published at a later date. He named the new genus Thylacosmilus, which means "pouch knife". He found the genus distinct enough to warrant a new subfamily within Borhyaenidae; Thylacosmilinae.[2]

The type species of the genus is T. atrox, based on the holotype specimen P 14531, which consists of the skull and a partial skeleton. Specimen P 14344 was designated as the paratype of T. atrox, and consists of the cranium, mandible, vertebrae, a femur, a tibia, a fibula, and tarsal bones. He also named a second species, T. lentis, based on specimen P 14474, a partial skull with teeth, from the same location. These specimens are housed at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.[2] In 1934, Riggs fully described the animal, after the fossils had been prepared and compared with other mammals from the same formation and better known borhyaenids from the Santa Cruz Formation.[3]

Though Thylacosmilus is one of several predatory mammal genera typically called "saber-toothed cats", it was not a felid placentalian, but a sparassodont, a group closely related to marsupials, and only superficially resembled other saber-toothed mammals due to convergent evolution.[4][5]

Evolution

The term "saber-tooth" refers to an ecomorph consisting of various groups of extinct predatory synapsids (mammals and close relatives), which convergently evolved extremely long maxillary canines, as well as adaptations to the skull and skeleton related to their use. This includes members of Gorgonopsia, Thylacosmilidae, Machaeroidinae, Nimravidae, Barbourofelidae, and Machairodontinae.[6][7]

The cladogram below shows the position of Thylacosmilus within Sparassodonta, according to Suarez and colleagues, 2015.[8]

| Sparassodonta |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

Thylacosmilus had large, saber-like canines. The roots of these canines grew throughout the animal's life, growing in an arc up the maxilla and above the orbits.[9] Thylacosmilus teeth are in many aspects even more specialized than the teeth of other sabertoothed predators. In these animals the predatory function of the "sabres" gave rise to a specialization of the general dentition, in which some teeth were reduced or lost. In Thylacosmilus the canines are relatively longer and more slender, relatively triangular in cross-section, in contrast with the oval shape of carnivorans' saber-like canines. The function of these large canines was once thought to have apparently even eliminated the need for functional incisors, while carnivorans like Smilodon and Barbourofelis still have a full set of incisors.[10] However, evidence in the form of wear facets on the internal sides of the lower canines of Thylacosmilus indicate that the animal did indeed have incisors, though they remain hitherto unknown due to poor fossilization and the fact that no specimen thus far has been preserved with its premaxilla intact.[11]

In Thylacosmilus there is also evidence of the reduction of postcanine teeth, which developed only a tearing cusp, as a continuation of the general trend observed in other sparassodonts, which lost many of the grinding surfaces in the premolars and molars. The canines were hypsodont and more anchored in the skull, with more than half of the tooth contained within the alveoli, which were extended over the braincase. They were protected by the large symphyseal flange and they were powered by the highly developed musculature of the neck, which allowed forceful downward and backward movements of the head. The canines had only a thin layer of enamel, just 0.25 mm in its maximum depth at the lateral facets, this depth being consistent down the length of the teeth. The teeth had open roots and grew constantly, which eroded the abrasion marks that are present in the surface of the enamel of other sabertooths, such as Smilodon. The sharp serrations of the canines were maintained by the action of the wear with the lower canines, a process known as thegosis.[10]

Although the postcranial remains of Thylacosmilus are incomplete, the elements recovered so far allow the examination of characteristics that this animal acquired in convergence with the sabertooth felids. Its cervical vertebrae were very strong and to some extent resembled the vertebrae of Machairodontinae;[12] also the cervical vertebrae have neural apophysis well developed, along with ventral apophysis in some cervicals, an element that is characteristic of other borhyaenoids. The lumbar vertebrae are short and more rigid than in Prothylacynus. The bones of the limbs, like the humerus and femur, are very robust, since they probably had to deal with larger forces than in the modern felids. In particular, the features of the humerus suggest a great development of the pectoral and deltoid muscles, not only required to capture its prey, also to absorb the energy of the impact of the collision with such prey.[13] The features of the hindlimb, with a robust femur equipped with a greater trochanter in the lower part, the short tibia and plantigrade feet shows that this animal was not a runner, and probably stalked its prey animals. The hindlimbs also allowed a certain mobility of the hip, and possibly the ability to stand up only with its hindlimbs, like Prothylacynus and Borhyaena. Contrary to felids, barbourofelids and nimravids, the claws of Thylacosmilus were not retractable.[13]

.jpg)

Body mass for sparassodonts is difficult to estimate, since these animals have relatively large heads in proportion to their bodies, leading to overestimations, particularly when compared with skulls of modern members of Carnivora, which have different locomotory and functional adaptations, or with those of the recent predatory marsupials, which do not exceed 30 kg of body mass. Recent methods, like Ercoli and Prevosti's (2011) linear regressions on postcranial elements that directly support the body's weight (such as tibiae, humeri and ulnae), comparing Thylacosmilus to both extinct and modern carnivorans and metatherians, suggest that it weighed between 80 to 120 kilograms (180 to 260 lb),[14][15] with one estimate suggesting up to 150 kg (330 lb),[16] about the same size as a modern jaguar. The differences in weight estimations may be due to the individual size variation of the specimens studied in each analysis, as well as the different samples and methods used. In any case, the weight estimations are consistent for terrestrial species that are generalists or have some degree of cursoriality.[15] A weight in this range would make Thylacosmilus one of the largest known carnivorous metatherians.

Palaeobiology

Recent comparative biomechanical analysis have estimated the bite force of T. atrox, starting from maximum gape, at 38 newtons (8.5 lbf), much weaker than that of a leopard, suggesting its jaw muscles had an insignificant role in the dispatch of prey. Its skull was similar to that of Smilodon in that it was much better adapted to withstand loads applied by the neck musculature, which, along with evidence for powerful and flexible forelimb musculature and other skeleton adaptations for stability, support the hypothesis that its killing method consisted on immobilization of its prey followed by precisely directed, deep bites into the soft tissue driven by powerful neck muscles.[17][18][19] It has been suggested that its specialized predatory lifestyle could be linked to more extensive parental care than in modern marsupial predators.[13]

Various studies have been published on the musculature and motion of Thylacosmilus.[20][21][22]

In 1988 Juan C. Quiroga published a study on the cerebral cortex of two proterotherids and Thylacosmilus. The study examines endocranial casts of two Thylacosmilus specimens: MLP 35-X-41-1 (from the Montehermosan age in Catamarca Province), which represents a natural cast of the left half of the cranial cavity lacking the anterior part of the olfactory bulbs and the brain hemispheres; and MMP[note 1] 1443 (from the Chapadmalalan age in Buenos Aires Province), which is a complete, artificial cast that shows some ventral displacement but with the anterior right part of the brain hemisphere and olfactory bulb. Quiroga's analysis showed that the somatic nervous system of Thylacosmilus represented 27% of the entire cortex, with the visual area representing 18% and the auditory area 7%. The paleocortex was more than 8%. The sulci of the cortex are relatively complex and similar in pattern and number to the modern diprotodont marsupials. Compared with Macropus and Trichosurus, Thylacosmilus had less development of the maxillar area with respect to the mandibular area, and the rhinal fissure is taller than in Macropus and Thylacinus. This disproportion between the maxillar and mandibular areas, which are roughly similar in marsupials, seems to be a consequence of the extreme development of the neck and mandibular musculature, used in the functioning of the osteodentary anatomy of this animal. However, the area dedicated to the oral-mandible region comprises 42% of the somatic area. The comparison between the endocranial casts of Thylacosmilus and a proterotherid specimen (possibly a species coevolving with Thylacosmilus and a potential prey item) indicates that Thylacosmilus had only half of the encephalization and a quarter of the cortical area, while some have more somatized areas, similar visual areas and less auditory area, which suggests different sensomotoric qualities between the animals.[23]

A 2005 study found that the bite forces of Thylacosmilus and Smilodon were low, which indicates the killing techniques of saber-toothed animals differed from those of extant species.[24]

A 2010 study found that the cranial morphology of Thylacosmilus and other metatherians was more similar to caniforms, despite them often being compared to felids.[25]

Distribution and habitat

Based on studies of its habitat, Thylacosmilus is believed to have hunted in savanna-like or sparsely forested areas, avoiding the more open plains where it would have faced competition with the more successful and aggressive Phorusrhacids it shared its environment with.[9] Fossils of Thylacosmilus have been found in the Huayquerian (Late Miocene) Ituzaingó, Epecuén, and Cerro Azul Formations and the Montehermosan (Early Pliocene) Brochero and Monte Hermoso Formations in Argentina.[26]

Extinction

Although older references have often stated that Thylacosmilus became extinct due to competition with the "more competitive" saber-toothed cat Smilodon during the Great American Interchange, newer studies have shown this is not the case. Thylacosmilus died out during the Pliocene (3.6 to 2.58 Ma) whereas saber-toothed cats are not known from South America until the Middle Pleistocene (781,000 to 126,000 years ago).[14] As a result, the last appearance of Thylacosmilus is separated from the first appearance of Smilodon by over one and a half million years.

Notes

- Museo Municipal de Ciencias Naturales de Mar del Plata Lorenzo Scaglia

References

- Forasiepi, Analía M. (2009). "Osteology of Arctodictis sinclairi (Mammalia, Metatheria, Sparassodonta) and phylogeny of Cenozoic metatherian carnivores from South America". Monografías del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. 6: 1–174.

- Riggs, E. S (1933). "Preliminary description of a new marsupial sabertooth from the Pliocene of Argentina". Geological Series of Field Museum of Natural History. 6: 61–66. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.5427.

- Riggs, E. S. (1934). "A New Marsupial Saber-Tooth from the Pliocene of Argentina and Its Relationships to Other South American Predacious Marsupials". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 24 (1): 1–32. doi:10.2307/3231954. JSTOR 3231954.

- Turnbull, W. D; Segall, W. (1984). "The ear region of the marsupial sabertooth, Thylacosmilus: Influence of the sabertooth lifestyle upon it, and convergence with placental sabertooths". Journal of Morphology. 181 (3): 239–270. doi:10.1002/jmor.1051810302. PMID 30037165.

- Argot, C. (2004). "Functional-adaptive features and palaeobiologic implications of the postcranial skeleton of the late Miocene sabretooth borhyaenoid Thylacosmilus atrox (Metatheria)". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 28 (1): 229–266. doi:10.1080/03115510408619283.

- Antón 2013, pp. 3–26.

- Meehan, T.; Martin, L. D. J. (2003). "Extinction and re-evolution of similar adaptive types (ecomorphs) in Cenozoic North American ungulates and carnivores reflect van der Hammen's cycles". Die Naturwissenschaften. 90 (3): 131–135. Bibcode:2003NW.....90..131M. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0392-1. PMID 12649755.

- Suárez, C.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Goin, F. J.; Jaramillo, C. (2015). "Insights into the Neotropics prior to the Great American Biotic Interchange: new evidence of mammalian predators from the Miocene of Northern Colombia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Online edition: e1029581. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1029581.

- Antón, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253010421.

- Turnbull, W. D., Butler, P. M., & Joysey, K. A. (1978). Another look at dental specialization in the extinct saber-toothed marsupial, Thylacosmilus, compared with its placental counterparts. Development, function and evolution of teeth. Academic Press, London, 399-414.

- Antón, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780253010421.

- Benes, Josef. Prehistoric Animals and Plants. Prague, Artua, 1979. Pg. 237-8

- Argot, Christine., 2002: Evolution of the locomotion in the Borhyaenoids Marsupialia, Mammalia Morphofunctional and phylogenetical study and paleoecological implications. Evolution de la locomotion chez les Borhyaenoides Marsupialia, Mammalia Etude morphofonctionnelle, phylogenetique et implications paleoecologiques. Bulletin de la Societe Zoologique de France, 1273: 291-300

- Prevosti, Francisco J.; Analia Forasiepi; Natalia Zimicz (2013). "The Evolution of the Cenozoic Terrestrial Mammalian Predator Guild in South America: Competition or Replacement?". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 20: 3–21. doi:10.1007/s10914-011-9175-9. hdl:11336/2663.

- Ercoli, Marcos D.; Francisco J. Prevosti (2011). "Estimación de masa de las especies de Sparassodonta (Mammalia, Metatheria) de edad Santacrucense (Mioceno Temprano) a partir del tamaño del centroide de los elementos apendiculares: inferencias paleoecológicas". Ameghiniana (in Spanish). 48 (4): 462–479. doi:10.5710/amgh.v48i4(347).

- Sorkin, B. (2008). "A biomechanical constraint on body mass in terrestrial mammalian predators". Lethaia. 41 (4): 333–347. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2007.00091.x.

- Hogenboom, M. (2013-07-02). "Sabretooth killing power depended on thick neck". BBC. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- Wroe, S; Chamoli, U; Parr, WCH; Clausen, P; Ridgely, R (2013-06-26). "Comparative Biomechanical Modeling of Metatherian and Placental Saber-Tooths: A Different Kind of Bite for an Extreme Pouched Predator". PLOS ONE. 8 (6): e66888. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...866888W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066888. PMC 3694156. PMID 23840547.

- Quiroga, J. C.; Dozo, M. T. (1988). "The brain of Thylacosmilus atrox. Extinct South American saber-tooth carnivore marsupial". Journal für Hirnforschung. 29 (5): 573–586. PMID 3216103.

- Turnbull, W. D. 1976. Restoration of masticatory musculature of Thylacosmilus. In Churcher, C. S. (ed) Athlon, Essays in Palaeontology in Honour of Loris Shano Russell. Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto), pp. 169-185.

- Turnbull W. D. 1978. Another look at dental specialization in the extinct saber-toothed marsupial, Thylacosmilus, compared with its placental counterparts. Pp. 399–414inButler P. M. and Joysey K. A., eds. Development, function and evolution of teeth. Academic Press, London.

- Argot, Christine., 2002: Evolution of the locomotion in the Borhyaenoids Marsupialia, Mammalia Morphofunctional and phylogenetical study and paleoecological implications Evolution de la locomotion chez les Borhyaenoides Marsupialia, Mammalia Etude morphofonctionnelle, phylogenetique et implications paleoecologiques. Bulletin de la Societe Zoologique de France, 1273: 291-300

- Quiroga, J. C. (1988). "Cuantificación de la corteza cerebral en moldes endocraneanos de mamíferos girencéfalos. Procedimiento y aplicación en tres mamíferos extinguidos". Ameghiniana (in Spanish). 25 (1): 67–84. ISSN 1851-8044.

- Wroe, S.; McHenry, C.; Thomason, J. (2005). "Bite club: comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behaviour in fossil taxa". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 272 (1563): 619–625. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2986. PMC 1564077. PMID 15817436.

- Goswami, A.; Milne, N.; Wroe, S. (2010). "Biting through constraints: cranial morphology, disparity and convergence across living and fossil carnivorous mammals". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1713): 1831–1839. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2031. PMC 3097826. PMID 21106595.

- Thylacosmilus at Fossilworks.org

Bibliography

- Antón, M. (2013). Sabertooth (1st ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01042-1. OCLC 857070029.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikispecies has information related to Thylacosmilus |