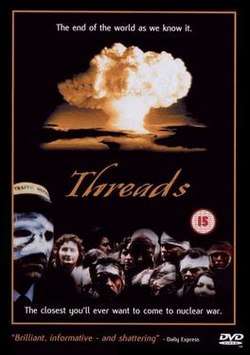

Threads (1984 film)

Threads is a 1984 British apocalyptic war drama television film jointly produced by the BBC, Nine Network and Western-World Television Inc. Written by Barry Hines and directed and produced by Mick Jackson, it is a dramatic account of nuclear war and its effects on the city of Sheffield in Northern England. The plot centres on two families as a confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union erupts. As the nuclear exchange between NATO and the Warsaw Pact begins, the film depicts the medical, economic, social and environmental consequences of nuclear war.

| Threads | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Drama Sci-fi War |

| Written by | Barry Hines |

| Directed by | Mick Jackson |

| Starring | |

| Original language(s) | English |

| Production | |

| Executive producer(s) | Graham Massey John Purdie |

| Producer(s) |

|

| Cinematography |

|

| Editor(s) |

|

| Running time | 112 minutes |

| Production company(s) |

|

| Distributor | BBC |

| Budget | £400,000[1] |

| Release | |

| Original network | BBC |

| Picture format | Colour |

| Audio format | Mono |

| Original release | 23 September 1984 |

Shot on a budget of £400,000, the film was the first of its kind to depict a nuclear winter. It has been called "a film which comes closest to representing the full horror of nuclear war and its aftermath, as well as the catastrophic impact that the event would have on human culture."[2] It has been compared to the earlier programme The War Game produced in Britain in the 1960s and its contemporary counterpart The Day After, a 1983 ABC television film depicting a similar scenario in the United States. It was nominated for seven BAFTA awards in 1985 and won for Best Single Drama, Best Design, Best Film Cameraman and Best Film Editor.

Plot

Young Sheffield residents Ruth Beckett and Jimmy Kemp intend to marry due to her unplanned pregnancy. As tensions between the US and the Soviet Union in Iran escalate, the Home Office directs Sheffield City Council to assemble an emergency operations team, which establishes itself in a makeshift bomb shelter in the basement of the town hall. After an ignored US ultimatum to the Soviets results in a brief tactical nuclear skirmish, Britain experiences fear, looting and rioting. "Subversives" including peace activists and some trade unionists are arrested and interned under the Emergency Powers Act.

Attack Warning Red is transmitted and Sheffield town hall staff react with "action, confusion and slight panic."[3] Amidst panic, a nuclear warhead air bursts high over the North Sea, producing an electromagnetic pulse; most electrical systems throughout the UK and northwestern Europe are destroyed. The first missile salvos hit NATO targets, including nearby RAF Finningley. Although the city is not yet heavily damaged, chaos reigns in the streets. Jimmy is last seen running from his stalled car to reach Ruth. Sheffield is targeted by a one-megaton warhead which air bursts directly above the Tinsley Viaduct. Strategic targets, including steel and chemical factories in the Midlands, are the primary targets. Two thirds of all UK homes are destroyed, and immediate deaths range between 12 and 30 million. Of 3,000 megatons total, about 210 fall on the UK.

Sheffield Town Hall is destroyed and traps the city's emergency operations team. They attempt to coordinate the city's emergency and relief efforts through their few remaining short-wave radios. Nuclear fallout from a ground burst at Crewe descends upon Sheffield. Jimmy's mother succumbs to radiation sickness and severe burns after being caught by the Tinsley Viaduct explosion. Jimmy's father searches for food and water. Fallout prevents the remaining functioning civil authorities from fighting fires or rescuing those trapped under debris. Ruth leaves her parents and grandmother in their basement, making her way to the Sheffield Royal Infirmary, where there is no electricity, running water, sanitation, or supplies. While she is absent, looters kill her parents and are executed.

By June, soldiers dig to the town hall basement but find the emergency staff have suffocated. Without the manpower or fuel to bury or burn the dead, an epidemic of communicable diseases spreads. The government authorizes capital punishment, and special courts execute criminals. The only viable currency becomes food, given as a reward for work or withheld as punishment. The millions of tons of soot, smoke and dust in the upper atmosphere trigger a nuclear winter. By July, without running water, electricity, or basic sanitation, Sheffield becomes uninhabitable. Ruth and thousands of other survivors defy official orders and leave the city. Many survivors die of radiation poisoning. Low-flying government light aircraft order them to return home. In Buxton, the police assign Ruth to a house. Once the policeman leaves, the home owner evicts her at gunpoint. At an outdoor soup kitchen, Ruth meets Bob, a pre-war acquaintance of Jimmy's. Ruth and Bob travel together, surviving on scavenged food, including the raw carcasses of radiation-poisoned livestock.

In September, Ruth takes part in the yearly harvest, accomplished using the last remaining petrol and raw human labour, but the nuclear winter keeps yields low. Ruth gives birth to her child in an abandoned barn. The army relies on rifles and tear gas for control.

Millions of people around the Northern Hemisphere have died due to radiation, fallout, starvation, exposure or the nuclear strikes. Sunlight returns, but food remains scarce due to the lack of equipment, fertilizers, and fuel. Damage to the ozone layer intensifies ultraviolet radiation, increasing cataracts and cancer.

Ten years later, Britain's population has fallen to medieval levels of about 4 to 11 million people. Survivors work the fields using primitive hand-held farming tools. Few children have been born or raised since the attack. They speak broken English due to poor education and the breakdown of family life. Prematurely aged and blind with cataracts, Ruth collapses in a field and dies, survived by her 10-year-old daughter Jane. The country begins to recover, resuming coal mining, producing limited electricity, and using steam power. The population continues to live in near-barbaric squalor.

Three years after Ruth's death, Jane and two boys are caught stealing food. One boy is shot in the ensuing confusion. Jane wrestles for the food with the other boy and they have sex.[4] Pregnant, Jane finds a makeshift hospital, gives birth to a stillborn child, and screams as she sees it.

Cast

Although Jackson initially considered casting actors from Granada Television's Coronation Street, he later decided to take a neorealist approach, and opted to cast relatively unknown actors in order to heighten the film's impact through the use of characters the audience could relate to.[5]

- Paul Vaughan as the Narrator

- Karen Meagher as Ruth Beckett

- Reece Dinsdale as Jimmy Kemp

- David Brierley as Mr Bill Kemp

- Rita May as Mrs Rita Kemp

- Nicholas Lane as Michael Kemp

- Jane Hazlegrove as Alison Kemp

- Phil Rose as Doctor Talbot

- Henry Moxon as Mr Beckett

- June Broughton as Mrs Beckett

- Sylvia Stoker as Granny Beckett

- Harry Beety as Clive J. Sutton (Controller)

- Ruth Holden as Marjorie Sutton

- Ashley Barker as Bob

- Michael O'Hagan as Chief Superintendent Hirst

- Phil Askham as Mr Stothard

- Anna Seymour as Mrs Stothard

- Fiona Rook as Carol Stothard

- Steve Halliwell as Information Officer

- Joe Holmes as Mr Langley

- Victoria O'Keefe as Jane

- Lesley Judd as TV newsreader

- Lee Daley as Spike

- Marcus Lund as Gaz

- Ian Parkinson & Tony Grant as Radio Announcers

Production and themes

Screenwriter Barry Hines[6]

Threads was first commissioned (under the working title Beyond Armageddon) by the Director-General of the BBC Alasdair Milne, after he watched the 1965 drama-documentary The War Game, which had not been shown on the BBC when it was made, due to pressure from the Wilson government, although it had had a limited release in cinemas.[7] Mick Jackson was hired to direct the film, as he had previously worked in the area of nuclear apocalypse in 1982, producing the BBC Q.E.D. documentary A Guide to Armageddon.[8][9] This was considered a breakthrough at the time, considering the previous banning of The War Game, which BBC staff believed would have resulted in mass suicides if aired. Jackson subsequently travelled around the UK and the US, consulting leading scientists, psychologists, doctors, defence specialists and strategic experts in order to create the most realistic depiction of nuclear war possible for his next film.[5] Jackson consulted various sources in his research, including the 1983 Science article Nuclear Winter: Global Consequences of Multiple Nuclear Explosions, penned by Carl Sagan and James B. Pollack. Details of a possible attack scenario and the extent of the damage were derived from Doomsday, Britain after Nuclear Attack (1983), while the ineffective post-war plans of the UK government came from Duncan Campbell's 1982 exposé War Plan UK.[10] In portraying the psychological damage suffered by survivors, Jackson took inspiration from the behaviour of the Hibakusha[7] and Magnus Clarke's 1982 book Nuclear Destruction of Britain.[10] Sheffield was chosen as the main location partly because of its "nuclear-free zone" policy that made the council sympathetic to the local filming[6] and partly because it seemed likely that the USSR would strike an industrial city in the centre of the country.[11]

Jackson hired Barry Hines to write the script because of his political awareness. The relationship between the two was strained on several occasions, as Hines spent much of his time on set, and apparently disliked Jackson on account of his middle class upbringing.[5] They also disagreed about Paul Vaughan's narration, which Hines felt was detrimental to the drama.[12] As part of their research, the two spent a week at the Home Office training centre for "official survivors" in Easingwold which, according to Hines, showed just "how disorganised [post-war reconstruction] would be."[13]

Auditions were advertised in The Star,[14] and took place in the ballroom of Sheffield City Hall, where 1,100 candidates turned up.[13] Extras were chosen on the basis of height and age, and were all told to look "miserable" and to wear ragged clothes; the majority were CND supporters.[12] The makeup for extras playing third-degree-burn victims consisted of Rice Krispies and tomato ketchup.[14] The scenes taking place six weeks after the attack were shot at Curbar Edge in the Peak District National Park; because weather conditions were considered too fine to pass off as a nuclear winter, stage snow had to be spread around the rocks and heather, and cameramen installed light filters on their equipment to block out the sunlight.[13]

In order for the horror of Threads to work, Jackson made an effort to leave some things unseen: "to let images and emotion happen in people’s minds, [o]r rather in the extensions of their imaginations."[12] He later recalled that while BBC productions would usually be followed by phone calls of congratulations from friends or colleagues immediately after airing, no such calls came after the first screening of Threads. Jackson later "realised...that people had just sat there thinking about it, in many cases not sleeping or being able to talk." He stated that he had it on good authority that Ronald Reagan watched the film when it aired in the US.[5] Along with Hines, Jackson also received a letter of praise from Labour leader Neil Kinnock, stating "[t]he dangers of complacency are much greater than any risks of knowledge."[12][15]

Broadcast and release history

Threads was a co-production of the BBC, Nine Network and Western-World Television, Inc. It was first broadcast on BBC Two on 23 September 1984 at 9:30 pm, and achieved the highest ratings on the channel (6.9 million) of the week.[6] It was repeated on BBC One on 1 August 1985 as part of a week of programmes marking the fortieth anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which also saw the first television screening of The War Game (which had been deemed too disturbing for television in the 20 years since it had been made). Threads was not shown again on British screens until the digital channel BBC Four broadcast it in October 2003.[17] It was also shown on UKTV Documentary in September 2004 and was repeated in April 2005.[18]

Threads was broadcast in the United States on cable network Superstation TBS on 13 January 1985,[19] with Ted Turner presenting the introduction.[20] This was followed by a panel discussion on nuclear war. It was also shown in syndication to local commercial stations and, later, on many PBS stations. In Canada, Threads was broadcast on Citytv in Toronto, CKVU in Vancouver[21] and CKND in Winnipeg,[22] while in Australia it was shown on the Nine Network on 19 June 1985.[23] Unusually for a commercial network, it broadcast the film without commercial breaks;[24] many commercial outlets in the United States and Canada that broadcast the film also did so without commercial interruption, or interrupting only for disclaimers or promos.

Threads was originally released by BBC Video (on VHS and, for a very short period, Betamax) in 1987 in the United Kingdom. The play was re-released on both VHS and DVD in 2000 on the Revelation label, followed by a new DVD edition in 2005. Due to licensing difficulties the 1987 release replaced Chuck Berry's recording of his song "Johnny B. Goode" with an alternative recording of the song. In all these cases, the original music over the opening narration was removed, again due to licensing problems; this was an extract from the Alpine Symphony by Richard Strauss, performed by the Dresden State Opera Orchestra, conducted by Rudolf Kempe (HMV ASD 3173).

In January 2018, journalist and nuclear threat expert Julie McDowall led a distributed viewing of the film, encouraging the audience to share their reactions on Twitter under the hashtag #threaddread, as part of a campaign to ask the BBC to show the movie for the first time since 2003.[12]

On 13 February 2018, Threads was released by Severin Films on Blu-ray in the United States. The programme was scanned in 2K from a broadcast print for this release, including extras such as an audio commentary with Director Mick Jackson and interviews with actress Karen Meagher, Director Of Photography Andrew Dunn, Production Designer Christopher Robilliard and film writer Stephen Thrower.[25][26] This is also the first home video release in which the extract from the Alpine Symphony remains intact.

On 9 April 2018, Simply Media released a Special Edition DVD in the UK, featuring a different 2K scan, restored and remastered from the original BBC 16mm CRI prints, which Severin did not have access to. This also featured the original music, for the first time on home video in the UK. Whereas the previous releases had no extra features, the Special Edition included commentaries and associated documentaries.

Reception

Initial

Threads was not widely reviewed, but the critics who reviewed it gave generally positive reviews.[27] John J. O'Connor of The New York Times wrote that the film "is not a balanced discussion about the pros and cons of nuclear armaments. It is a candidly biased warning. And it is, as calculated, unsettlingly powerful."[28] Rick Groen of The Globe and Mail wrote that "[t]he British crew here, headed by writer Barry Hines and producer/director Mick Jackson, accomplish what would seem to be an impossible task: depicting the carnage without distancing the viewer, without once letting him retreat behind the safe wall of fictitious play. Formidable and foreboding, Threads leaves nothing to our imagination, and Nothingness to our conscience."[29] In his movie guide, Leonard Maltin gave the film a rating of three stars (out of a possible four). He called Threads "Britain's answer to The Day After" and wrote that the film was "unrelentingly graphic and grim, sobering, and shattering, as it should be."[30]

Retrospective

Retrospective reviews have been very positive. On Metacritic, the film has a score of 92 based on 5 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim",[31] whilst it has a Rotten Tomatoes score of 100% based on 10 reviews (with an average score of 8.7/10).[27] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian called it a "masterpiece", writing: "It wasn’t until I saw Threads that I found that something on screen could make me break out in a cold, shivering sweat and keep me in that condition for 20 minutes, followed by weeks of depression and anxiety."[32] Sam Toy of Empire gave the film a perfect score, writing that "this British work of (technically) science fiction teaches an unforgettable lesson in true horror" and went on to praise its ability "to create an almost impossible illusion on clearly paltry funds."[33] Jonathan Hatfull of SciFiNow gave a perfect score to the remastered DVD of the film. "No one ever forgets the experience of watching Threads. [...It] is arguably the most devastating piece of television ever produced. It’s perfectly crafted, totally human and so completely harrowing you’ll think that you’ll probably never want to watch it again." He praised the pacing and Hines' "impeccable" screenplay and described its portrayal of the "immediate effects" of the bombing as "jaw-dropping [...] watching the survivors in the days and weeks to come is heart-breaking."[34] Both Little White Lies and The A.V. Club have emphasized the film's contemporary relevance, especially in light of political events such as Brexit.[35][36] According to the former, the film paints a "nightmarish picture of a Britain woefully unprepared for what is coming, and reduced, when it does come, to isolation, collapse and medieval regression, with a failed health service, very little food being harvested, mass homelessness, and the pound and the penny losing all value."[35]

Awards and nominations

The film was nominated for seven BAFTA awards in 1985. It won for Best Single Drama, Best Design, Best Film Cameraman and Best Film Editor. Its other nominations were for Best Costume Design, Best Make-Up, and Best Film Sound.[37]

See also

- Able Archer 83, NATO command post exercise that resulted in the 1983 nuclear war scare and changed thinking about nuclear war in Britain.

- List of nuclear holocaust fiction

- Nuclear weapons in popular culture

- Nuclear weapons and the United Kingdom

- Operation Square Leg, a military analysis of the effects of a nuclear war on Britain.

- Protect and Survive, the 1970s British government information films on nuclear war.

- When the Wind Blows, a 1986 animated British film that shows a nuclear attack on Britain by the Soviet Union from the viewpoint of a retired couple.

- Testament, a 1983 film about a nuclear explosion over the United States

- The Day After, a 1983 TV-film that follows a nuclear explosion over the Midwestern United States

References

- Audio Commentary: Mick Jackson. Threads. Dir. Mick Jackson. 1984. Blu-ray. Severin Films, 2018.

- "Film and the Nuclear Age: Representing Cultural Anxiety" By Toni A. Perrine, p. 237 on Google books.

- Mangan, Michael, ed. (1990). Threads and Other Sheffield Plays. Critical Stages. 3. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-850-75140-3. ISSN 0953-0533.

- Mangan, Michael, ed. (1990). Threads and Other Sheffield Plays. Critical Stages. 3. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-850-75140-3. ISSN 0953-0533.

- "End of the world revisited: BBC's Threads is 25 years old". The Scotsman. 5 September 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Kibble-White, Jack (September 2001). "Let's All Hide in the Linen Cupboard". Off The Telly.

- Binnion, Paul (May 2003). "Threads" (PDF). Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies. University of Nottingham. ISSN 1465-9166.

- Q.E.D.: A Guide to Armageddon (TV Episode 1982) on IMDb

- QED: A Guide to Armageddon. Nuclear war facts from the 1980s on YouTube

- Hall, Kevin (21 January 2013). "Threads – Select References and Bibliography". Fallout Warning. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Mike Jackson's commentary on 2018 Special Edition

- Rogers, Jude (17 March 2018). "Here come the bombs: the making of Threads, the nuclear war film that shocked a generation". www.newstatesman.com. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- Bean, Patrick (3 January 2002). "Threads by Barry Hines". Archived from the original on 29 May 2010.

- "Nuclear fallout in Sheffield". BBC South Yorkshire. 22 April 2005. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Whitelaw, Paul (21 November 2013). "Threads – box set review". The Guardian.

- Bartlett, Andrew (2004). "Nuclear Warfare in the Movies". Anthropoetics. UCLA. 10 (1). ISSN 1083-7264. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Bunn, Mike (23 June 2010). "Threads – BBC Film Review". Suite 101.

- "Sheffield film 'Threads' - Megathread. | Sheffield Fourm". www.sheffieldforum.co.uk. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Clark, Kenneth R. (11 January 1985). "'Threads': Nightmare After the Holocaust". Chicago Tribune.

- WTBS introduction Threads 1985

- Threads on CKVU 1984

- CKND - Introduction to Threads (1985)

- Carlton, Mike (26 June 1985). "Clive has a certain appeal, despite the colonial cringe". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Hutchinson, Garrie (27 June 1985). "Threads: A Devastating Piece Of TV". The Age.

- "Threads Review (Severin Films Blu-ray)". Cultsploitation. 15 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- Michele "Izzy" Galgana (29 January 2018). "Blu-ray Review: THREADS Still Destroys". ScreenAnarchy. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Threads at Rotten Tomatoes

- The New York Times 12 February 1985, p.42

- The Globe and Mail 2 March 1985

- Maltin, Leonard (2006). Leonard Maltin's 2007 Movie Guide. USA: Signet. pp. 1348. ISBN 0-451-21916-3.

- Threads, retrieved 28 April 2019

- Bradshaw, Peter (20 October 2014). "Threads: the film that frightened me most". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- Toy, Sam (1 January 2000). "Threads". Empire. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- "Threads remastered DVD review: this is the way the world ends". SciFiNow. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- "Discover the post-apocalyptic nightmare of this landmark social drama".

- "Threads served up a bleakly British depiction of our impending nuclear doom".

- "Awards database". BAFTA. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Threads (1984 film) |

- 'Threads' in pictures at BBC South Yorkshire

- Threads on IMDb

- Threads at AllMovie

- Threads at the BFI's Screenonline