The Remains of the Day (film)

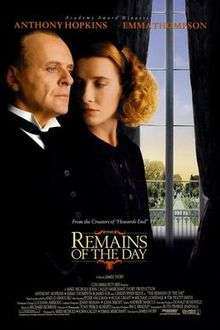

The Remains of the Day is a 1993 British-American drama film and adapted from the Booker Prize-winning 1989 novel of the same name by Kazuo Ishiguro. The film was directed by James Ivory, produced by Ismail Merchant, Mike Nichols, and John Calley and adapted by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. It stars Anthony Hopkins as James Stevens and Emma Thompson as Miss Kenton, with James Fox, Christopher Reeve, and Hugh Grant in supporting roles.

| The Remains of the Day | |

|---|---|

Theatrical-release poster | |

| Directed by | James Ivory |

| Produced by | |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Richard Robbins |

| Cinematography | Tony Pierce-Roberts |

| Edited by | Andrew Marcus |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 134 minutes |

| Country | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million |

| Box office | $63.9 million[2] |

The film was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor (Hopkins), Best Actress (Thompson) and Best Adapted Screenplay (Jhabvala). In 1999, the British Film Institute ranked The Remains of the Day the 64th greatest British film of the 20th century.[3]

Plot

In 1958 post-war Britain, Stevens, the butler of Darlington Hall, receives a letter from Miss Kenton, a former colleague employed as the housekeeper some twenty years earlier, now separated from her husband. Their former employer, The Earl of Darlington, has died a broken man, his reputation destroyed after he was exposed as a Nazi sympathizer, and his stately country manor has been sold to a retired United States Congressman, Mr. Jack Lewis. Stevens is granted permission to borrow Lewis' Daimler, and he sets off to the West Country to see Miss Kenton, in the hope that she will return as housekeeper.

The film flashes back to Kenton's arrival as housekeeper in the 1930s. The ever-efficient Stevens manages the household well, taking great pride in and deriving his entire identity from his profession. Miss Kenton, too, proves to be a valuable servant, and she is equally efficient and strong-willed, but also warmer and less repressed. Stevens and Kenton occasionally butt heads, particularly when she observes that Stevens' father (also a former butler) is in failing health and no longer able to perform his duties, which Stevens stubbornly refuses to acknowledge. Stevens' professional dedication is fully displayed when, while his father lies dying, he steadfastly continues his butler duties.

Relations between Stevens and Kenton eventually thaw, and it becomes clear she has feelings for him. Despite their proximity and shared purpose, Stevens' outward detachment remains unchanged; his first and only loyalty is to his service as Lord Darlington's butler. In a scene of agonised repression, Miss Kenton embarrasses Stevens when she catches him reading a book. Curious, she forces it out of his hand, and finds to her disappointment it is an ordinary romance novel; Stevens explains to Miss Kenton he was reading it only to improve his vocabulary, and asks her not to invade his private time again.

Meanwhile, Darlington Hall is regularly frequented by politicians of the interwar period, and many of Lord Darlington's guests are like-minded, fascist-sympathizing British and European aristocrats, with the exception of the more pragmatic Congressman Lewis, who does not share the "noble instincts" of Lord Darlington and his guests. Lewis informs the "gentleman politicians" in his midst that they are meddling amateurs and that "Europe has become the arena of Realpolitik" and warns them they are "headed for disaster." Later, Lord Darlington's aristocratic guests grill Stevens about his political knowledge to prove that the lower classes are ignorant and unworthy to have an opinion, but Stevens steadfastly refuses to acknowledge that he has ever listened to their conversations, being too busy serving.

Darlington later meets Prime Minister Chamberlain and the German Ambassador, and uses his influence to try to broker a policy of appeasement towards Nazi Germany, based on his belief that Germany had been unfairly treated by the Treaty of Versailles following the First World War and only desires peace. In the midst of these events, and after overhearing Sir Geoffrey Wren praising Nazi racial laws, Darlington suddenly requests that two newly-appointed German-Jewish maids, both refugees, should be dismissed, despite Stevens's mild protest that they are good workers. Nevertheless, Stevens carries out Lord Darlington's command, despite a horrified Miss Kenton threatening to resign in protest. Miss Kenton later confides in Stevens that she has no family and nowhere to go should she leave Darlington Hall, and is ashamed to not follow up on her threat to resign. Stevens does not mention that he disagreed with Lord Darlington's order and leaves Miss Kenton with the impression that he didn't care about the girls' fate.

Lord Darlington's godson, journalist Reginald Cardinal, is appalled by the nature of the secret meetings in Darlington Hall. Concurring with Congressman Lewis' earlier protestations, Cardinal tells Stevens that Lord Darlington is a pawn, being used by the Nazis. Despite Cardinal's indignation, Stevens does not denounce or criticise his master, feeling it is not his place to judge his employer's honorable intentions, even if they are incorrect. Later, Lord Darlington expresses regret for having dismissed Ilsa and Irma, the two German-Jewish maids. He asks Stevens to locate them and Stevens questions Miss Kenton as to the maids' whereabouts. (It is revealed they had returned to Germany, but their ultimate fate is unknown.)

Eventually, Miss Kenton forms a relationship with a former co-worker, Tom Benn, who proposes marriage and asks Miss Kenton to move away with him to run a coastal boarding house. Miss Kenton mentions this proposal to Stevens, in effect offering him an ultimatum, but Stevens will not admit his feelings, offering Miss Kenton only his congratulations. Miss Kenton leaves Darlington Hall prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. Before Miss Kenton's departure, Stevens finds her crying in frustration, but the only response he can muster is to call her attention to a neglected domestic task.

En route to meeting Miss Kenton in 1958, when asked by locals about his former employer, Stevens at first denies having served or even having met Lord Darlington, but later admits to having served and respected him. He says that, while Lord Darlington was unable to correct his terrible error, he is now on his way in the hope that he can correct his own. He meets Miss Kenton (though separated, still Mrs Benn), and they reminisce. Stevens mentions in conversation that Lord Darlington's godson, Reginald Cardinal, was killed in the war. He also says Lord Darlington died from a broken heart after the war, having sued a newspaper for libel, losing the suit and his reputation in the process. Stevens reveals that in his declining years, Lord Darlington at times failed to recognise Stevens and carried on conversations with no one else in the room.

Miss Kenton declines Stevens's offer to return to Darlington Hall, wishing instead to remain near her grown daughter, whom she has just that day learned is pregnant. She also implies that she will go back to her husband, because, despite being unhappy in their marriage for many years, in all the world he needs her the most. As they part, Miss Kenton is emotional, while Stevens is still unable to demonstrate any feeling. Back in Darlington Hall, Lewis asks Stevens if he remembers much of the old days, to which Stevens replies that he was too busy serving. A pigeon then becomes trapped in the hall, and is eventually freed by the two men, leaving both Stevens and Darlington Hall far behind.

Cast

- Anthony Hopkins as Mr James Stevens

- Emma Thompson as Miss Sarah "Sally" Kenton (later Mrs Benn)

- James Fox as The Earl of Darlington (Lord Darlington)

- Christopher Reeve as Congressman Jack Lewis

- Peter Vaughan as Mr William Stevens ("Mr Stevens, Sr")

- Hugh Grant as Reginald Cardinal (Lord Darlington's godson)

- John Haycraft as Auctioneer

- Caroline Hunt as Landlady

- Michael Lonsdale as Dupont d'Ivry

- Jeffry Wickham as Viscount Bigge

- Paula Jacobs as Mrs Mortimer

- Ben Chaplin as Charlie

- Steve Dibben as George (footman no. 2)

- Abigail Harrison as Housemaid

- Rupert Vansittart as Sir Geoffrey Wren

- Patrick Godfrey as Spencer

- Peter Halliday as Canon Tufnell

- Peter Cellier as Sir Leonard Bax

- Frank Shelley as Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

- Peter Eyre as The 3rd Viscount Halifax (Lord Halifax)

- Terence Bayler as Trimmer

- Hugh Sweetman as Scullery Boy

- Tony Aitken as Postmaster

- Emma Lewis as Elsa

- Joanna Joseph as Irma

- Tim Pigott-Smith as Tom Benn

- John Savident as Doctor Meredith

- Lena Headey as Lizzie

- Paul Copley as Harry Smith

- Pip Torrens as Doctor Carlisle

- Brigitte Kahn as a German Freifrau (Baroness)

- Wolf Kahler as German Ambassador Joachim von Ribbentrop

Production

A film adaptation of the novel was originally planned to be directed by Mike Nichols from a script by Harold Pinter. Some of Pinter's script was used in the film, but, while Pinter was paid for his work, he asked to have his name removed from the credits, in keeping with his contract.[lower-alpha 1] Christopher C. Hudgins observes: "During our 1994 interview, Pinter told [Steven H.] Gale and me that he had learned his lesson after the revisions imposed on his script for The Handmaid's Tale, which he has decided not to publish. When his script for The Remains of the Day was radically revised by the James Ivory-Ismail Merchant partnership, he refused to allow his name to be listed in the credits" (125).[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4] Though no longer the director, Nichols remained associated with the project as one of its producers.

The music was recorded at Windmill Lane Studios in Dublin.

Settings

A number of English country estates were used as locations for the film, partly owing to the persuasive power of Ismail Merchant, who was able to cajole permission for the production to borrow houses not normally open to the public. Among them were Dyrham Park for the exterior of the house and the driveway, Powderham Castle (staircase, hall, music room, bedroom; used for the aqua-turquoise stairway scenes), Corsham Court (library and dining room) and Badminton House (servants' quarters, conservatory, entrance hall). Luciana Arrighi, the production designer, scouted most of these locations. Scenes were also shot in Weston-super-Mare, which stood in for Clevedon. The pub where Mr Stevens stays is the Hop Pole in Limpley Stoke; the shop featured is also in Limpley Stoke. The pub where Miss Kenton and Mr Benn meet is The George Inn in Norton St Philip.

Characters

The character of Sir Geoffrey Wren is based loosely on that of Sir Oswald Mosley, a British fascist active in the 1930s.[4] Wren is depicted as a strict vegetarian.[5] The 3rd Viscount Halifax (later created The 1st Earl of Halifax) also appears in the film. Lord Darlington tells Stevens that Halifax approved of the polish on the silver, and Lord Halifax himself later appears when Darlington meets secretly with the German Ambassador and his aides at night. Halifax was a chief architect of the British policy of appeasement from 1937 to 1939.[6] The character of Congressman Jack Lewis in the film is a composite of two separate American characters in Kazuo Ishiguro's novel: Senator Lewis (who attends the pre-WW2 conference in Darlington Hall), and Mr Farraday, who succeeds Lord Darlington as master of Darlington Hall.

Soundtrack

| The Remains of the Day | |

|---|---|

| Film score by | |

| Released | 1993 |

| Length | 49:26 |

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Entertainment Weekly | A link |

The original score was composed by Richard Robbins. It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Score, but lost to Schindler's List.

- Track listing

- Opening Titles, Darlington Hall – 7:27

- The Keyhole and the Chinaman – 4:14

- Tradition and Order – 1:51

- The Conference Begins – 1:33

- Sei Mir Gegrüsst (Schubert) – 4:13

- The Cooks in the Kitchen – 1:34

- Sir Geoffrey Wren and Stevens, Sr. – 2:41

- You Mean a Great Deal to This House – 2:21

- Loss and Separation – 6:19

- Blue Moon – 4:57

- Sentimental Love Story/Appeasement/In the Rain – 5:22

- A Portrait Returns/Darlington Hall/End Credits – 6:54

Critical reception

The film has a 95% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 42 reviews, with an average rating of 8.46/10. The consensus states: "Smart, elegant, and blessed with impeccable performances from Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson, The Remains of the Day is a Merchant-Ivory classic."[7] Roger Ebert particularly praised the film, calling it "a subtle, thoughtful movie."[8] In his favorable review for The Washington Post, Desson Howe wrote, "Put Anthony Hopkins, Emma Thompson and James Fox together and you can expect sterling performances."[9] Vincent Canby of The New York Times said, in another favorable review, "Here's a film for adults. It's also about time to recognize that Mr. Ivory is one of our finest directors, something that critics tend to overlook because most of his films have been literary adaptations."[10]

The film was named as one of the best films of 1993 by over 50 critics, making it the fifth most acclaimed film of 1993.[11]

Awards and nominations

The film is #64 at the British Film Institute's "Top 100 British films".

The film was also nominated for the American Film Institute's "100 Years...100 Passions" list.[12]

Notes

- "In November 1994, Pinter wrote, "I've just heard that they are bringing another writer into the "Lolita" film. It doesn't surprise me.' ... Pinter's contract contained a clause to the effect that the film company could bring in another writer, but that in such a case he could withdraw his name (which is exactly the case with [the film] The Remains of the Day-he had insisted on this clause since the bad experience with revisions made to his Handmaid's Tale script); he has never been given any reason as to why another writer was brought in" (Gale 352).

- Hudgins adds: "We did not see Pinter's name up in lights when Lyne's Lolita finally made its appearance in 1998. Pinter goes on in the March 13 [1995] letter [to Hudgins] to state that 'I have never been given any reason at all as to why the film company brought in another writer,' again quite similar to the equally ungracious treatment that he received in the Remains of the Day situation" (125).

- Cf. the essay on the film The Remains of the Day published in Gale's collection by Edward T. Jones: "Pinter gave me a copy of his typescript for his screenplay, which he revised 24 January 1991, during an interview that I conducted with him in London about his screenplay in May 1992, part of which appeared in 'Harold Pinter: A Conversation' in Literature/Film Quarterly, XXI (1993): 2–9. In that interview, Pinter mentioned that Ishiguro liked the screenplay that he had scripted for a proposed film version of the novel. All references to Pinter's screenplay in the text [of Jones's essay] are to this unpublished manuscript" (107n1).

- In his 2008 essay published in The Pinter Review, Hudgins discusses further details about why "Pinter elected not to publish three of his completed film scripts, The Handmaid's Tale, The Remains of the Day and Lolita," all of which Hudgins considers "masterful film scripts" of "demonstrable superiority to the shooting scripts that were eventually used to make the films"; fortunately ("We can thank our various lucky stars"), he says, "these Pinter film scripts are now available not only in private collections but also in the Pinter Archive at the British Library"; in this essay, which he first presented as a paper at the 10th Europe Theatre Prize symposium, Pinter: Passion, Poetry, Politics, held in Turin, Italy, in March 2006, Hudgins "examin[es] all three unpublished film scripts in conjunction with one another" and "provides several interesting insights about Pinter's adaptation process" (132).

References

- "The Remains of the Day". BFI. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "The Remains of the Day". Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- British Film Institute - Top 100 British Films (1999). Retrieved August 27, 2016

- "Four Weddings actor visits Creebridge". Galloway Gazette. 26 November 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- Giblin, James Cross (2002). The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler. New York: Clarion Books. p. 175. ISBN 9780395903711.

vegetarian.

- Lee, David (2010). Stanley Melbourne Bruce: Australian Internationalist. London: Continuum. pp. 121–122. ISBN 9780826445667.

- "The Remains of the Day". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Ebert, Roger (5 November 1993). "The Remains Of The Day Movie Review (1993) | Roger Ebert". Rogerebert.suntimes.com. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- "'The Remains of the Day'". Washingtonpost.com. 5 November 1993. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- Canby, Vincent (5 November 1993). "Movie Review – The Remains of the Day – Review/Film: Remains of the Day; Blind Dignity: A Butler's Story". Movies.nytimes.com. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/style/1994/01/09/86-thumbs-up-for-once-the-nations-critics-agree-on-the-years-best-movies/1bbb0968-690e-4c02-9c8b-0c3b4b5b4a1e/

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0107943/awards?ref_=tt_awd

Bibliography

- Gale, Steven H. Sharp Cut: Harold Pinter's Screenplays and the Artistic Process. Lexington, Ky.: The University Press of Kentucky, 2003.

- Gale, Steven H., ed. The Films of Harold Pinter. Albany: SUNY Press, 2001.

- Hudgins, Christopher C. "Harold Pinter's Lolita: 'My Sin, My Soul'." In The Films of Harold Pinter. Steven H. Gale, ed. Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press, 2001.

- Hudgins, Christopher C. "Three Unpublished Harold Pinter Filmscripts: The Handmaid's Tale, The Remains of the Day, Lolita." The Pinter Review: Nobel Prize / Europe Theatre Prize Volume: 2005 – 2008. Francis Gillen with Steven H. Gale, eds. Tampa, Fla.: University of Tampa Press, 2008.