The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science

The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science (1909) is a highly critical account of the life of Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, and the early history of the Christian Science church in 19th-century New England. Largely ghostwritten by the novelist Willa Cather, it was published as a book in November 1909 in New York by Doubleday, Page & Company.[1][2] The original byline was that of a journalist, Georgine Milmine, but it later emerged that Cather was the principal author.[1][3]

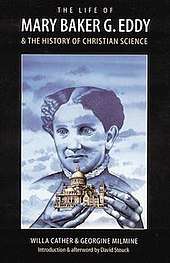

The 1993 University of Nebraska Press cover, the first to name Willa Cather as co-author | |

| Author |

|

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Genre | Biography, history |

| Publisher |

|

| Pages | 566 (first edition) |

| ISBN | 0-8032-6349-X |

| OCLC | 150493 |

| Website | Text available at the Internet Archive |

The first major examination of Eddy's life and work, the material initially appeared in McClure's magazine in 14 installments between January 1907 and June 1908,[4] when Eddy was 85 years old, preceded in December 1906 by a six-page editorial announcing the series as "probably as near absolute accuracy as history ever gets".[5] In the early 20th century, Christian Science became the fastest growing religion in America,[6] and in the view of McClure's, Eddy was the most powerful woman in the country.[7] The McClure's eyewitness accounts and affidavits became key primary sources for practically all independent accounts of the church's early history.[8][9]

The magazine's publisher and editor-in-chief, S. S. McClure, assigned five writers to work on the articles: Willa Cather, winner of the 1923 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, who had joined McClure's as an editor in 1906; Georgine Milmine, a freelance reporter who originally brought some of the research to McClure's; Will Irwin, McClure's managing editor; staff writer Burton J. Hendrick, winner of a Pulitzer Prize in 1921, 1923 and 1929; staff writer Mark Sullivan; and, briefly, the journalist Ida Tarbell.[10]

The New York Times wrote in 1910 that the book's evidence against "Eddyism" was "unanswerable and conclusive".[11] Christian Scientists reacted strongly to it; there were reports of Scientists buying all available copies and stealing it from libraries.[12] The Christian Science church purchased the manuscript, and soon the book was out of print.[13] It was republished by Baker Book House in 1971 after its copyright had expired, and again in 1993 by the University of Nebraska Press, this time naming both Cather and Milmine as authors. David Stouck, in his introduction to the University of Nebraska Press edition, wrote that Cather's portrayal of Eddy "contains some of the finest portrait sketches and reflections on human nature that Willa Cather would ever write".[14]

Christian Science

Eddy and 26 followers founded the Christian Science church in 1879 in Boston, Massachusetts,[15] following the publication of her book Science and Health (1875). In the book Eddy argued that disease is a mental error rather than a physical disorder, and that it should be treated not by medicine but by a form of silent prayer that corrects the mistaken beliefs. Her ideas were not new, she said; on the contrary, the church sought to "reinstate primitive Christianity and its lost element of healing".[16]

At a time when medical practice was in its infancy, and patients often fared better if left alone, the Christian Science message was a welcome one.[17][lower-alpha 1] In 1882 Eddy set up the Massachusetts Metaphysical College in Boston, where, for $300 for a 12-lesson course, she and her students taught mostly women how to become Christian Science practitioners, licensed to offer Christian Science prayer to the sick.[19] The college made Eddy a wealthy woman; when she died in December 1910 her estate was valued at $1.5 million (equivalent to $41.16 million in 2019).[20]

Christian Science became the fastest growing religion in the United States. The church had 27 members in 1879; 65,717 in 1906 when McClure's began its research; and 268,915 at its height in 1936.[21] In 1890 there were just seven Christian Science churches in the US; by 1910 there were 1,104.[22] Construction of the mother church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, was completed in Boston in December 1894, and in 1906 the Mother Church Extension, rising 224 ft and accommodating nearly 5,000, was built at a cost of $2 million (equivalent to $56.91 million in 2019), reportedly paid by Christian Scientists around the world.[23] Art historian Paul Ivey writes that, for many, the building "visibly declared that Christian Science had, indeed, arrived as a major force in American religious life".[24] The religion entered a period of continuous decline after World War II for various reasons, chiefly the improvement in medical science, the availability of more jobs for women outside the home,[25] and the tendency of those raised within the religion to leave it.[26] In 2009 it was estimated that there were under 50,000 Christian Scientists in the US.[27]

Publication

McClure's articles

The McClure's articles were published in 14 installments between January 1907 and June 1908, under Georgine Milmine's byline, as "Mary Baker G. Eddy: The Story of Her Life and the History of Christian Science". The series was preceded by a seven-page editorial in December 1906, outlining the difficulties of the investigation and explaining why it was being published.[28] The editorial got the series off to an unfortunate start by reproducing a photograph that purported to be of Eddy but was in fact of someone else.[29] Referring to Christian Science as a cult based on a "hazy and obscure" book, it continued: "A church which has doubled its membership in five years, which draws its believers mostly from the rich and respectable ... and which has just paid for the most costly church building in New England—to the worldly, this is no longer a joke":[7]

In 1875 no one living outside of two or three back streets of Lynn had heard of Christian Science. Now, the very name is a catch phrase. In those early days the leader and teacher paid out half of her ten dollars a week to hire a hall, patching out the rest of her living with precarious fees as an instructor in mental healing; now, she is one of the richest women in the United States. She is more than that—she is the most powerful American woman.[7]

The editorial accused the church of a lack of transparency: "The Christian Science mind is unfriendly to independent investigation. It presupposes that anything even slightly unfavorable to Mrs. Eddy or to Christian Science is deliberate falsehood."[30]

Synopsis

The book's criticism of Eddy is considerable. She is portrayed as greedy, uneducated and deceitful, someone who regularly revised her life story and was interested only in making money. The authors produce witness statements from Eddy's childhood in Bow, New Hampshire, alleging that she engaged in repeated fainting spells to gain attention, particularly from her father, and that, as an adult, she developed a habit of appearing to be seriously ill only to recover quickly.[lower-alpha 2]

Eddy was widowed when she was 22 years old and pregnant, after which she returned to live in her father's home. Her son was raised there for the first few years of his life, looked after by domestic staff because of Eddy's poor health. The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy alleges that she allowed him to be adopted when he was four. According to Eddy, she was unable to prevent the adoption.[lower-alpha 3] Women in the United States at the time could not be their own children's guardians, per the legal doctrine of coverture.[lower-alpha 4]

Her next two marriages, lifelong poor health, and the numerous legal actions in which she was involved, are examined in detail—including lawsuits she initiated against her students; a criminal case in which her third husband was accused of conspiring to murder one of them (an allegation never proven); her belief that her former students killed her third husband by using "mental malpractice"; and her legal adoption of a 41-year-old homeopath when she was 67. The authors allege that Eddy's major work, Science and Health, which became Christian Science's main religious text, borrowed heavily from the work of Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, a New England faith healer. Quimby had treated Eddy in the years before his death and had given her some of his unpublished notes.

The series and book discuss the rewrites of Science and Health by her editor James Henry Wiggin,[34] who edited the book from the 16th edition in 1886 until the 50th in 1891, including the 22 editions that appeared between 1886 and 1888.[35] In a letter to a friend in December 1889, published by McClure's in October 1907, Wiggin alleged that Eddy's preference that her writing remain unclear was one of the "tricks of the trade".[36] She is an "awfully (I use the word advisedly) smart woman," he wrote, "acute, shrewd, but not well read, nor in way learned".[37] There is nothing to really understand in 'Science and Health'", he continued, "except that God is all, and yet there is no God in matter! What they fail to explain is, the origin of the idea of matter, or sin. They say it comes from mortal mind, and that mortal mind is not divinely created, in fact, has no existence ... that matter and disease are like dreams ... No, Swedenborg, and all other such writers, are sealed books to [Mrs. Eddy]. She cannot understand such utterances, and never could, but dollars and cents she understands thoroughly."[36][38]

Wiggin emphasized that she was a practical woman. She advised her students, "Call a surgeon in surgical cases." One asked: "What if I find a breech presentation in childbirth?" She replied: "You will not, if you are in Christian Science." The student asked again: "But if I do?" Eddy advised: "Then send for the nearest regular practitioner!" Wiggin concluded: "You see, Mrs. Eddy is nobody's fool."[36][39]

Authorship

Editorial team

Born in Ontario, Canada, Georgine Milmine had worked for the Syracuse Herald in New York before joining McClure's as a researcher. She had been collecting material about Eddy for years—newspaper articles from the 1880s, court records, and a first edition of Science and Health, all of which were hard to obtain—but lacked the resources to check and write it up herself, so she sold it to McClure's.[40] Apparently when McClure's was sold, the new publisher threw away the research, including the first edition.[41]

S. S. McClure assigned five writers to the story: Milmine, Willa Cather, Burton J. Hendrick, political columnist Mark Sullivan, and Will Irwin. When the series was suggested, the journalist Ida Tarbell was also involved.[10] Cather had started working at McClure's as a fiction editor in 1906 when she was 32 years; she worked there until 1912, for most of the time as managing editor.[2] Cather reportedly spent from December 1906 until May 1908 in Boston, checking the sources and writing up the research.[42][43] The journalist Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant, a friend of Cather's, wrote in 1953 that S. S. McClure saw Eddy as a "natural" for the magazine, because of her marital history and idiosyncrasies:

The material was touchy, and would attract a world of readers both of the faithful and the doubters. ... The job seemed to [Cather] a little infra dig, not on the level where she cared to move. But she inspired confidence, had the mind of a judge and the nose of a detective when she needed it.[44]

Willa Cather's authorship

Manuscript

The Christian Science church purchased the book's manuscript and holds it in the church's Mary Baker Eddy Library in Boston. According to David Stouck, professor emeritus of English at Simon Fraser University and author of several books on Willa Cather, Cather's handwriting is evident on the manuscript in edits for the typesetter and notes with queries.[45] Several of Cather's later characters appear to have been modeled on her portrait of Eddy, including Myra Henshawe in My Mortal Enemy (1926).[46]

Reluctant to discuss most of her work before O Pioneers! (1913), Cather told her father and close friends that she was the author of Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy but told others that her role had not been significant.[47] According to L. Brent Bohlke of Bard College, editor of Willa Cather in Person (1990), Cather regarded the Eddy book as poorly written. While it contains some excellent writing and character analysis, Bohkle wrote, it is not well-structured; the editing failed to rid the book of the serialized nature of the McClure's pieces.[48] Cather wanted to distance herself from journalism, according to Stouck, and sought to minimize her role in the articles because they had angered the Christian Science church.[45]

Early letters

Cather identified herself as the author on December 17, 1906, in a letter to her father, Charles F. Cather, in which she wrote that the articles beginning February 1907 (at the time written but not published) were hers.[45] Apologizing for being unable to come home for Christmas, she explained that she had to get the March article ready: "But if you were here, my father, you'd tell me to stand by my job and not to desert Mr. McClure in this crisis. It would mean such a serious loss to him in money and influence not to have the March article come out—Everyone would think he was beaten and scared out, for the articles are under such a glare of publicity and such a fire of criticism. I had nothing to do with the January article remember, my work begins to appear in February. Mr. McClure is ill from worry and anxiety ...".[49] She referred to her authorship again in a letter to the writer Harrison G. Dwight on January 12, 1907:

Mr. McClure tried three men on this disagreeable task, but none of them did it very well, so a month ago it was thrust upon me. You may imagine me wandering around the country grubbing among newspaper files and court records for the next five months. It is the most laborious and sordid work I have ever come upon, and it takes every hour of my time and as much vitality as I can put into it.

She continued: "You can't know, never having done it, how such work does sap your poor brain and wring it dry of anything you'd like to pretend was there. I jump about like a squirrel in a cage and wonder how I got here and why I am doing it. I never in my life wanted to do this sort of thing. I have a clean conscience on that score. Then why am I hammering away at it, I'd like to know? I often wonder whether I shall ever write another line of anything I care to."[50]

Letter to Edwin Anderson

.jpg)

In 1982 Brent L. Bohlke discovered that Cather had written on November 24, 1922, to a friend, Edwin H. Anderson, director of the New York Public Library, confirming that she was the author of the entire book except for the first chapter.[51][52][41][53] Georgine Miline had brought the research to McClure's, she wrote, "a splendid collection of material", but Milmine lacked the technical skills to write it up:

Mr. McClure tried out three or four people at writing the story. It was a sort of competition. He liked my version the best chiefly because it was unprejudiced—I haven't the slightest bone to pick with Christian Science. This was when I first came to New York, and that piece of writing was the first important piece of work I did for magazines. After I finished it, I became Managing Editor."[51][52]

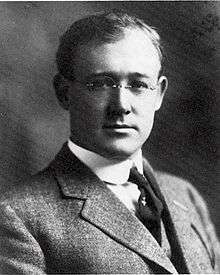

Burton J. Hendrick (who went to work for the book's publisher, Doubleday, founded in 1897 as Doubleday & McClure Company) had written the first installment, Cather told Anderson, but it had been based largely on rumor: "with what envious people and jealous relatives remember of Mrs. Eddy's early youth". She said Hendrick was "very much annoyed at being called off the job and never forgave Mr. McClure". As for the other 13 installments: "A great deal of time and money were spent on authenticating all the material, and with the exception of the first chapter, I think the whole history is as authentic and accurate as human performances ever are." She added: "Miss Milmine, now Mrs. Wells, is in the awkward position of having her name attached to a book, of which she didn't write a word."[51][52]

Cather believed Frank Nelson Doubleday, Doubleday's co-founder, should have promoted the book more: "Undoubtedly, Doubleday has perfectly good business reasons for keeping the book out of print. There has been a great demand for it to which he has been consistently blank. You see nobody took any interest in its fate. I wrote it myself as a sort of discipline, an exercise. I wouldn't fight for it; it's not the least in my line." She asked Anderson to keep what she had told him confidential: "I have never made a statement about it before, in writing or otherwise. I suppose somebody ought to know the actual truth of the matter and so long as I am writing to you about it, I might as well ask you to be the repository of these facts. I know, of course, that you want them for some perfectly good use, and will keep my name out of it."[51][52]

Cather left a clause in her will forbidding the publication of her letters and private papers, which meant that for many years her letters could only be paraphrased by scholars.[54] The correspondence entered the public domain in the United States on 1 January 2018, 70 years after her death in April 1947.[55] Nevertheless, the Willa Cather Trust permitted the publication of selected letters in 2013, including the letter to Anderson.[56]

Early public indications

In letters to others, Cather continued to deny her authorship; she told Genevive Richmond in 1933 and Harold Goddard Rugg in 1934 that she had helped only to organize and rewrite parts of the material.[45] An early public suggestion of her authorship was made by the columnist Alexander Woollcott in the New Yorker in February 1933: "And speaking of ghostwriters and Mrs. Eddy, I have recently learned on almost (if not quite) the best authority in the world that the famous pathfinding predecessor of all these [Eddy] biographies—the devastating series published in McClure's under the name of Georgine Milmine in the brave days of 1906—were not actually written by Miss Milmine at all. Instead, a re-write job based on the manuscript of her researches was assigned to a minor member of the McClure staff who has since made quite a name for herself in American letters. That name is Willa Cather."[57]

In March 1935, the Los Angeles Times reported that a copy of the book listed for sale by Philip Duschnes, a New York bookseller, was found to contain an editor's note that the book had been written by Cather.[lower-alpha 5] Witter Bynner, an associate editor for McClure's when the series and book were published, had signed the book on February 12, 1934, and added: "The material was brought to McClure's by Miss Milmine, but was put into the painstaking hands of Willa Cather for proper presentation, so that a great part of it is her work."[48]

Responses

Mary Baker Eddy's response

In a statement published by the Christian Science Sentinel on January 19, 1907, Eddy responded to the early installments in McClure's by challenging its description of her father, early family life, and the issues surrounding her marriages. McClure's had said that the Bible was the only book in the house when she was growing up; on the contrary, she wrote, her father was a great reader. To counter McClure's claim that her childhood home had provided a "lonely and unstimulating existence", her statement described the educational and professional achievements of her family. In response to McClure's description of her as bad tempered, she offered as an example of her kindness that a housekeeper of the family's had resigned because Eddy allowed a blind girl, who had knocked on the door and was unknown to the family, to stay with them.[29]

Church response

According to Peter Lyon in his biography of S. S. McClure, when the series began, three Christian Science officials arrived at the McClure's offices and asked an editor, Witter Bynner, to take them to McClure:

The Christian Scientists came in. Before they sat down, they stood on chairs and closed the transoms over the two doors to the rooms. Then they made their demand: the series must not be published. S.S. scowled at them and said nothing. To fill the silence, Brynner began rather nervously to assure the Scientists that the articles were not sensational, not offensive; that there was no cause for apprehension; that all the facts had been most carefully verified. ...

One of the Scientists cut in to suggest that perhaps there would be no objection to publication of the material if the Scientists were permitted to edit it as they might please.[59]

When McClure refused, they said he would soon notice a loss of advertising.[59] The church purchased the manuscript when the book appeared, and there were rumors that the plates had been destroyed.[13] In June 1920 it also purchased some of McClure's research files from a New York manuscript dealer, including notes from Milmine and drafts of the book handwritten by Cather.[60] Christian Scientists were reported to have bought and destroyed copies of the book, and removed them from libraries.[13] Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant wrote in 1953 that the book "disappeared almost immediately from circulation—the Christian Scientists are said to have bought the copies". It became scarce even in libraries. According to Sergeant, readers in the 1950s were likely to have to borrow it from the chief librarian and be watched while reading it.[61]

Baker Book House edition

The book's copyright expired 28 years after publication.[lower-alpha 6] Baker Book House, a Christian publishing house, republished it in 1971 "in the interest of fairness and objectivity", according to its back cover.[13] The introduction by Stewart Hudson explored Cather's involvement in the authorship and the influence of Eddy on several of Cather's characters, particularly Enid Royce and her mother in One of Ours.[62][63]

University of Nebraska Press edition

Caroline Fraser writes that the church tried to stop the University of Nebraska Press from republishing the book in 1993. The press was interested in doing so, under its Bison Books imprint with a new introduction by David Stouck, because the articles and book were Cather's first extended work and therefore important in her development as a writer.[64] They obtained a copy of the original 1909 edition, by then hard to come by, from the Leon S. McGoogan Library of Medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha.[65] According to Fraser, the head of the church's public-relations office, the Committee on Publication, called the press and told them the reprint might damage the church's and Eddy's reputation. According to a press representative who spoke to Fraser, the church representative "felt it was his responsibility to try to bully us into stopping publication or into saying that the book was worthless".[64]

Stouck made clear his view in the book's preface that Willa Cather was "indisputably the principal author".[45] But, according to Fraser, there were fears for the jobs of the church researchers who had helped make the Cather–Milmine manuscript available for examination.[64] Stouck therefore agreed to add a statement to the book, which, in Fraser's view, was essentially a church press release:

Since the Bison re-issue of The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science went to press new materials have come to light which suggest that Ms. Eddy's enemies may have played a significant role in organizing the materials for the "Milmine" biography. New information about Georgine Milmine, moreover, suggests that she would have welcomed biased opinion for its sensational and commercial value. The exact nature of Willa Cather's part in the compiling and writing of the biography remains, accordingly, a matter for further scholarly investigation.[65]

The "enemies" Stouck refers to relate to the "Next Friends" lawsuit that was initiated in March 1907, after the McClure's serialization had begun.[66] It was filed by Eddy's relatives, including her son, who maintained that she was unable to manage her own affairs; had it succeeded, she would have lost control of the church and her fortune. The suit was funded by Joseph Pulitzer, owner of the New York World; his motive, Fraser wrote, was to engineer a story about Eddy to rival that of McClure's.[67] The McClure's journalists were allegedly in touch with the litigants.[66] According to Fraser, the head of the church's Committee on Publication included the following in a report for its 1993 annual meeting:

A major corrective opportunity this year involved the rerelease of one of the earliest malicious biographies of Mrs. Eddy, The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science by Georgine Milmine. Dating from the yellow journalism period, this book was published in an attempt to discredit her. The current publisher, after much correspondence with our office, instead issued a statement accurately characterizing its bias. The book has received almost no attention in the public, proving if Truth isn't spoken, nothing is said.[68]

Reception and influence

The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy became a key primary source for biographies of Eddy that were published independently of the church. It influenced Lyman Pierson Powell's Christian Science: The Faith and its Founder (1907); Edwin Franden Dakin's Mrs. Eddy: The Biography of a Virginal Mind (1929); Ernest Sutherland Bates and John V. Dittemore's Mary Baker Eddy: The Truth and the Tradition (1932);[9] and Martin Gardner's The Healing Revelations of Mary Baker Eddy (1993).[8] Robert Peel, a life-long Christian Scientist and member of the church's Committee on Publication, also used it extensively as a source in his own three-part biography of Eddy (1966–1977).[63]

A New York Times reviewer wrote in February 1910 that the book "ranks among the really great biographies—or would were its subject of more intrinsic importance":

Since this Life first appeared in McClure's Magazine not one important statement as of fact in it has been disproved or even seriously questioned. It is a product of much and highly intelligent labor, and were Christian Scientists open to argument or amenable to reason the wretched cult would not have survived its publication for a single month. It is unanswerable and conclusive, and nobody who has not read it can be considered well-informed as to the history or nature of Eddyism.[11]

Also in February 1910, a reviewer in The Nation compared the book to Ida Tarbell's The History of the Standard Oil Company (1904), which similarly began as a series in McClure's and hastened the demise of the company: "Miss Milmine, like Miss Tarbell, is plainly not in sympathy with the persons or the movement she describes. But the indictment, if we choose to call it that, is framed dispassionately. The damaging evidence is elaborately built up and skilfully arranged, but the reader is left largely to form his own conclusions." Arguing that the result is "an historical record of high value and of fascinating interest", the reviewer concluded that the book "demolishes Mrs. Eddy without necessarily demolishing Christian Science".[69]

Reviewing the book in the American Historical Review in July 1910, I. Woodbridge Riley, author of The Faith, the Falsity and the Failure of Christian Science (1925), wrote that the book's value lay in part that it was an analysis of a woman by a woman, and that it unearthed early primary sources, such as court testimony and Eddy's ads for herself as a mental healer. It did not make enough of Eddy's hypochondria and delusions of persecution, but it nevertheless "offers a strangely interesting human document. Mrs. Eddy is more than a personality, she is a type. Given the free field of a democracy she illustrates the possibilities of a shrewd combination of religion, mental medicine, and money."[70]

The journalist Adela Rogers St. Johns, a minister in the Church of Religious Science—a belief system closely related to Christian Science—wrote in 1974 that Cather was "a fine—maybe our finest—American woman novelist" but also a "lousy unscrupulous reporter", arguing that she had "stirred with grim fancy the most vicious and inaccurate of all the attacks on Mrs. Eddy".[71] David Stouck, in his introduction to the 1993 University of Nebraska Press edition, wrote that Cather's portrayal of Eddy "contains some of the finest portrait sketches and reflections on human nature that Willa Cather would ever write".[14] In a letter to The New York Review of Books in 2000, Gillian Gill disagreed that the book offers an accurate portrayal of Eddy; she argued, for example, that the story of Eddy having "fits" as a child to get her own way, or the way McClure's described them, was "invented more or less out of whole cloth" by McClure's journalist Burton Hendrick, and that the accounts of Eddy as "hysterical" were misogynist.[66]

Publication history

- "Editorial announcement", McClure's, December 1906.

- Georgine Milmine, "Mary Baker G. Eddy: The Story of Her Life and the History of Christian Science", McClure's, January 1907 – June 1908 (14 installments).

- Georgine Milmine, The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science, New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1909 (archive.org).

- Georgine Milmine, The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science, Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1971, with an introduction by Stewart Hudson.

- Willa Cather and Georgine Milmine, The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science, Lincoln: Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press, 1993, with an introduction and afterword by David Stouck. ISBN 0-8032-6349-X

Sources

Notes

- When one of its first Christian Science practitioners opened a clinic with Eddy in Lynn in 1870, local people would say: "Go to Dr. Kennedy. He can't hurt you, even if he doesn't help you."[18]

- Cather and Milmine (1993): "These attacks, which continued until very late in Mrs. Eddy's life, have been described to the writer by many eye-witnesses, some of whom have watched by her bedside and treated her in Christian Science for her affliction. At times the attack resembled convulsions. Mary fell headlong to the floor, writhing and screaming in apparent agony. ... At home the family worked over her, and the doctor was sent for, and Mary invariably recovered rapidly after a few hours; but year after year her relatives fully expected that she would die in one of these spasms."[31]

- Mary Baker Eddy (1891): "A few months before my father's second marriage ... my little son, about four years of age, was sent away from me, and put under the care of our family nurse, who had married, and resided in the northern part of New Hampshire. I had no training for self-support, and my home I regarded as very precious. The night before my child was taken from me, I knelt by his side throughout the dark hours, hoping for a vision of relief from this trial. ..."My dominant thought in marrying again was to get back my child, but after our marriage his stepfather was not willing he should have a home with me. A plot was consummated for keeping us apart. The family to whose care he was committed very soon removed to what was then regarded as the Far West."After his removal a letter was read to my little son, informing him that his mother was dead and buried. Without my knowledge a guardian was appointed him, and I was then informed that my son was lost. Every means within my power was employed to find him, but without success."[32]

- Harvard Business School, 2010: "A married woman or feme covert was a dependent, like an underage child or a slave, and could not own property in her own name or control her own earnings, except under very specific circumstances. When a husband died, his wife could not be the guardian to their under-age children."[33]

- Los Angeles Times, 3 March 1935: "In the Fifteenth Catalogue of Philip Duschnes, 507 Fifth avenue, New York is listed, among many modern first editions, an item that will come as a surprise to many collectors. It seems that Miss Cather's third published book bore on its title page the name of 'Georgine Milmine'. It was "The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy," and it appeared in 1909. In the copy offered is a photostat of a note from one of the McClure's editors to this effect."[58]

- The Copyright Act of 1909 extended copyright from 14 to 28 years; see "An Act to Amend and Consolidate the Acts Respecting Copyright", 1 July 1909, here for background information.

References

- Bohlke 1982, 288–294.

- Jewell and Stout 2014, 97.

- Stouck 1993a, xv–xviii.

- Milmine 1907–1908.

- McClure's, December 1906, 216.

- Stark 1998, 190.

- McClure's, December 1906, 211.

- Gardner 1993, 41.

- Gill 1998, 567.

- The New York Times, February 26, 1910.

- Streissguth 2011, 42.

- Fraser 1999, 139.

- Stouck 1993a, xviii.

- Eddy 1908, 17–18; Stark 1998, 189.

- Peters 2007, 92; Wilson 1961, 125; Eddy 1908, 17.

- Stark 1998, 197–198.

- Milmine, May 1907, 97–98; also see Peel 1966, 222, 239.

- Bates and Dittemore 1932, 258, 274.

- The New York Times, December 15, 1910.

- Stark 1998, 189–191.

- Cunningham 1967, 892.

- Classe 2013, 58.

- Ivey 1999, 73.

- Stark 1998, 211–212.

- Stark 1998, 202, 208.

- Prothero and Callahan 2017, 165.

- McClure's, December 1906.

- Eddy 1907.

- McClure's, December 1906, 217.

- Cather and Milmine 1993, 21–22.

- Eddy 1891, 20–21.

- Harvard Business School, undated.

- Milmine, October 1907, 695–699.

- Bates and Dittemore 1932, 270–273, 304; Gottschalk 1973, 42.

- Milmine, October 1907, 699.

- Milmine, October 1907, 698–699.

- Cather and Milmine 1909, 336–338.

- Cather and Milmine 1909, 339.

- Stouck 1993, xv.

- Bohlke 1982, 291–292.

- Porter 2010, 71.

- Bohlke 1982, 289.

- Sergeant 1953, 55.

- Stouck 1993a, xvii.

- Stouck 1993a, xix.

- Bohlke 1982, 288.

- Bohlke 1982, 290.

- Jewell and Stout 2014, 99.

- Jewell and Stout 2014, 101.

- Cather, November 24, 1922.

- Stout 2002, 98, letter number 649.

- Stouck 1993a, xvi; Stouck 1993b, 500–501; Jewell and Stout 2014, 330–331.

- Perrotta 2013.

- Stout 2002, xi, 98, letter 649.

- Jewell and Stout 2014, 330–331.

- Woolcott 1933.

- Los Angeles Times, 3 March 1935.

- Lyon 1963, cited in Fraser 1999, 138–139.

- "Georgine Milmine Collection".

- Sergeant 1953, 56.

- Isaacson 1971.

- Stouck 1993b, 499.

- Fraser 1999, 140.

- Stouck 1993a, front matter.

- Gill 2000.

- Fraser 1999, 137.

- Fraser 1999, 140–141.

- The Nation, 1910.

- Riley 1910, 898–900.

- Bohlke and Hoover 2001, 58; for the Church of Religious Science, see McLellan 1988.

Works cited

- News sources and websites are listed in the References section only.

- Bates, Ernest Sutherland and Dittemore, John V. Mary Baker Eddy: The Truth and the Tradition, New York: A. A. Knopf, 1932.

- Bohlke, L. Brent. "Willa Cather and The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy", American Literature, 54(2), May 1982, 288–294. JSTOR 2926137

- Bohlke, L. Brent; Hoover, Sharon. Willa Cather Remembered, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

- Cather, Willa. Letter to Edward H. Anderson, November 24, 1922, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library. Reproduced in Andrew Jewell and Janis Stout (eds.), The Selected Letters of Willa Cather, New York: Vintage Books, 2014, 330–331. Also see "Letter 0649", "All Known Letters", Willa Cather Archive, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, 13.

- Cather, Willa and Milmine, Georgine. The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science, Lincoln: Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

- Classe, Olive. "Boston: The First Church of Christ, Scientist", in Trudy Ring, Noelle Watson, Paul Schellinger (eds.), The Americas: International Dictionary of Historic Places, New York: Routledge, 2013.

- Cunningham, Raymond J. "The Impact of Christian Science on the American Churches, 1880–1910", The American Historical Review, 72(3), April 1967 (885–905), 892. JSTOR 1846660

- Eddy, Mary Baker. Retrospection and Introspection, Boston: The First Church of Christ Scientist, 1920 [1891].

- Eddy, Mary Baker. Manual of the Mother Church, Boston: The First Church of Christ, Scientist, 89th edition, 1908 [1895].

- Eddy, Mary Baker. "Reply to McClure's Magazine", Christian Science Sentinel, January 19, 1907. Also in The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany, 1913,

- "Editorial announcement", McClure's, December 1906.

- Fraser, Caroline. God's Perfect Child: Living and Dying in the Christian Science Church, New York: Metropolitan Books, 1999.

- Gardner, Martin. The Healing Revelations of Mary Baker Eddy, Amherst, Prometheus Books, 1993.

- Gill, Gillian. Mary Baker Eddy, Boston: Da Capo Press, 1998.

- Gill, Gillian; reply by Caroline Fraser. "Mrs. Eddy's Voices", The New York Review of Books, June 29, 2000.

- Gottschalk, Stephen. The Emergence of Christian Science in American Religious Life, University of California Press, 1973.

- Rose Levine Isaacson, "Bio of Mary Baker Eddy Sheds Fascinating Light", Clarion-Ledger, 11 July 1971.

- Ivey, Paul Eli. Prayers in Stone: Christian Science Architecture in the United States, 1894–1930, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

- Jewell, Andrew; Stout, Janis (eds.). The Selected Letters of Willa Cather, New York: Vintage Books, 2014 [2013].

- Kennedy, Joseph S. "Columnist's words influence politics", Philadelphia Inquirer, 2 May 2004.

- Los Angeles Times. "Willa Cather", "Gossip of the Book World", March 3, 1935, 36.

- Lyon, Peter. Success Story: The Life and Times of S. S. McClure, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1963.

- Mary Baker Eddy Library, Christian Science church. "Georgine Milmine Collection", archived December 12, 2012 (WebCite).

- McLellan, Dennis. "Adela Rogers St. Johns", Los Angeles Times, 1988.

- Milmine, Georgine. "Mary Baker G. Eddy: The Story of Her Life and the History of Christian Science", McClure's, January 1907 – June 1908.

- Milmine, Georgine. "Mrs. Eddy and Her First Disciples", "Mary Baker G. Eddy: The Story of Her Life and the History of Christian Science", McClure's, installment V, May 1907.

- Milmine, Georgine. "Literary Activities", "Mary Baker G. Eddy: The Story of Her Life and the History of Christian Science", McClure's, installment IX, October 1907.

- Peel, Robert. Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Discovery, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966 (later published by the Christian Science Publishing Society).

- Perrotta, Tom. "Entirely Personal", The New York Times, April 25, 2013.

- Peters, Shawn Francis. When Prayer Fails: Faith Healing, Children, and the Law. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Porter, David H. On the Divide: The Many Lives of Willa Cather. University of Nebraska Press, 2010 [2008].

- Prothero, Donald and Callahan, Timothy D. UFOs, Chemtrails, and Aliens: What Science Says, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2017.

- Riley, I. Woodbridge. "Milmine: Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy", American Historical Review, July 1910.

- Sergeant, Elizabeth Shepley. Willa Cather: A Memoir, Philadelphia and New York: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1953.

- Stark, Rodney. "The Rise and Fall of Christian Science", Journal of Contemporary Religion, 13(2), 1998, 189–214.

- Stouck, David. "Introduction", in Willa Cather and Georgine Milmine, The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

- Stouck, David. "Afterword", in Willa Cather and Georgine Milmine, The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

- Stout, Janis P. A Calendar of the Letters of Willa Cather, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

- Streissguth, Tom. Writer of the Plains: A Story about Willa Cather, Millbrook Press, 2011.

- The Nation. "The Origins of Christian Science", February 10, 1910.

- The New York Times. "Mrs. Eddy's Life and Teachings", February 26, 1910.

- The New York Times. "Church gets most of her estate", December 15, 1910.

- Wilson, Bryan R. "Christian Science", in Sects and Society: A Sociological Study of the Elim Tabernacle, Christian Science, and Christadelphians, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961.

- "Women and the Law", Women, Enterprise & Society, Harvard Business School, archived 24 August 2019.

- Woollcott, Alexander. "Shouts & Murmurs: Take off those Whiskers", The New Yorker, February 4, 1933, 34.

External links

- "Mary Baker G. Eddy: The Story of Her Life and the History of Christian Science", McClure's, installments I–XIV, May 1907 – June 1908.

- "Training the Vine: A Study in Mrs. Eddy's Prerogatives and Powers", McClure's, installment XIII, May 1908, Project Gutenberg.

- "Mrs. Eddy's Book and Doctrine", McClure's, installment XIV, June 1908, Project Gutenberg.

- Fraser, Caroline. "Mrs. Eddy Builds Her Empire", New York Review of Books, 11 July 1996 (includes a review).

- Westberg, M. Victor and Robert David Thomas. "Christian Science: An Exchange", New York Review of Books, 14 November 1996 (letters in response to the above; reply from Fraser).