The Legend of Zelda (video game)

The Legend of Zelda[lower-alpha 2] is a 1986 action-adventure video game developed and published by Nintendo and designed by Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka.[7] Set in the fantasy land of Hyrule, the plot centers on an elf-like boy named Link, who aims to collect the eight fragments of the Triforce of Wisdom in order to rescue Princess Zelda from the antagonist, Ganon.[8] During the course of the game, the player controls Link from a top-down perspective and navigates throughout the overworld and dungeons, collecting weapons, defeating enemies and uncovering secrets along the way.[9]

| The Legend of Zelda | |

|---|---|

_gold.png) North American box art, including a cutout in the upper-left corner with a visible gold cartridge | |

| Developer(s) | Nintendo EAD |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | |

| Producer(s) | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| Designer(s) | Takashi Tezuka |

| Programmer(s) | |

| Writer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | Koji Kondo |

| Series | The Legend of Zelda |

| Platform(s) |

|

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

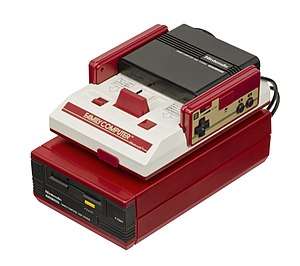

The first game of The Legend of Zelda series, it was originally released in Japan as a launch game for the Family Computer Disk System peripheral in February 1986.[10] More than a year later, North America and Europe received releases on the Nintendo Entertainment System in cartridge format, being the first home console game to include an internal battery for saving data.[11] This version was later released in Japan in 1994 under the title The Hyrule Fantasy: The Legend of Zelda 1.[lower-alpha 3][6] The game was ported to the GameCube[12] and Game Boy Advance,[6] and is available via the Virtual Console on the Wii, Nintendo 3DS and Wii U.[13] It was also one of 30 games included in the NES Classic Edition system, and is available on the Nintendo Switch through the NES Switch Online service.

The Legend of Zelda was a critical and commercial success for Nintendo. The game sold over 6.5 million copies, launched a major franchise, and has been regularly featured in lists of the greatest video games of all time. A sequel, Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, was first released in Japan for the Famicom Disk System less than a year after its predecessor, and numerous additional successors and spinoffs have been released in the decades since its debut.

Gameplay

The Legend of Zelda incorporates elements of action, adventure, and role-playing genres. The player controls Link from a flip-screen overhead perspective as he travels the overworld, a large outdoor map with various environments.[9] While the player begins the game armed only with a small shield, a tantalizing cave immediately beckons them within, where a sword is entrusted to Link by an old man for use as their primary weapon with the auspicious first message, “IT’S DANGEROUS TO GO ALONE! TAKE THIS”.[14] Throughout the adventure, Link will find or acquire various items that increase his abilities further; from Heart Containers that increase his life meter, to magic rings that decrease the amount of damage Link takes from enemy attacks, to stronger swords that let Link do more damage to enemies. These items are mainly found in caves scattered throughout the land. Some are easily accessible, while others are hidden beneath obstacles such as rocks, trees, and waterfalls.[15] Deadly creatures roaming about everywhere drop Rupees, the game's currency, when defeated and Rupees can also be found in hidden treasure chests all over the game world. Rupees are used to buy equipment from shops such as bombs and arrows.

Hidden on the overworld are entrances to the large underworld dungeons housing the pieces of the Triforce of Wisdom;[16] Each a unique, maze-like layout of rooms connected by doors and secret passages, often barred by monsters which must be defeated or blocks moved to gain entrance.[17] Dungeons also contain useful items which Link can add to his inventory, such as a boomerang for stunning enemies and retrieving distant items, and a magical recorder that let's Link teleport to the entrance of any dungeon he has previously cleared.[18] By successfully completing each dungeon to obtain all eight pieces of the Triforce of Wisdom, the artifact allows entrance to the final dungeon to defeat Ganon and rescue Zelda.[19] Apart from this exception, the order in which the game may be completed by traversing any given dungeon on the overworld is largely flexible to players, although they do steadily increase in difficulty by number, and some rooms can only be passed by using items gained in previous locations. There are even dungeons with secret entrances which must be uncovered while freely wandering the overworld, after acquiring useful items. This great freedom of where to go and what to do at any point allows for many ways of progressing through the game. It is even possible to reach the final boss without receiving the normally vital sword at its outset.[20]

After initially completing the game, one can begin its more difficult version referred to as the "Second Quest" (裏ゼルダ, Ura Zeruda, lit. "other Zelda"),[21][22] which alters many locations, secrets, and includes entirely distinct dungeons, with stronger enemies as well.[23] Although more difficult "replays" were not unique to Zelda, few games offered completely different levels upon the second playthrough.[20] By starting a new file with the name entered as "ZELDA", this mode can instead be accessed without needing to beat the game first.[24]

Plot and characters

Setting

Within the official Zelda Chronology, The Legend of Zelda takes place in an Era called "The Era of Decline", which exists within an alternative reality. In this era, Hyrule has been reduced to a small kingdom where the residents now live in caves, setting the background for The Legend of Zelda.[25]

Story

The story of The Legend of Zelda is described in the instruction booklet and during the short prologue which plays after the title screen: A small kingdom in the land of Hyrule is engulfed by chaos when an army led by Ganon, the Prince of Darkness, invaded and stole the Triforce of Power, one part of a magical artifact which alone bestows great strength.[8] In an attempt to prevent him from acquiring the Triforce of Wisdom, another of the three pieces, Princess Zelda splits it into eight fragments and hides them in secret underground dungeons.[8] Before eventually being kidnapped by Ganon, she commands her nursemaid Impa to find someone courageous enough to save the kingdom.[8] While wandering the land, the old woman is surrounded by Ganon's henchmen, when a young boy named Link appears and rescues her.[8] Upon hearing Impa's plea, he resolves to save Zelda and sets out to reassemble the scattered fragments of the Triforce of Wisdom, with which Ganon can then be defeated.[8]

During the course of the tale, Link locates and braves the eight underworld labyrinths, and beyond their defeated guardian monsters retrieves each fragment. With the completed Triforce of Wisdom, he is able to infiltrate Ganon's hideout in Death Mountain, confronting the prince of darkness and destroying him with the Silver Arrow.[26] Obtaining the Triforce of Power from Ganon's ashes, Link returns it and the restored Triforce of Wisdom to the rescued Princess Zelda, and peace can return to Hyrule.[27]

History

Development and Japanese release

The Legend of Zelda was directed and designed by Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka (credited as S. Miyahon and Ten Ten respectively in the closing credits).[7][28] Miyamoto produced the game, and Tezuka wrote the story and script.[28][29] Keiji Terui, a screenwriter who worked on anime shows such as Dr. Slump and Dragon Ball, wrote the backstory for the manual, drawing inspiration from conflicts in medieval Europe.[2] Development began in 1984, and the game was originally intended to be a launch game for the Famicom Disk System.[30] The development team worked on The Legend of Zelda and Super Mario Bros. concurrently, and tried to separate their ideas: Super Mario Bros. was to be linear, where the action occurred in a strict sequence, whereas The Legend of Zelda would be the opposite.[7] In Mario, Miyamoto downplayed the importance of the high score in favor of simply completing the game.[31] This concept was carried over to The Legend of Zelda. Miyamoto was also in charge of deciding which concepts were "Zelda ideas" or "Mario ideas." Contrasting with Mario, Zelda was made non-linear and forced the players to think about what they should do next.[32] According to Miyamoto, those in Japan were confused and had trouble finding their way through the multi-path dungeons, and in initial game designs, the player would start with the sword already in their inventory. Rather than merely simplifying matters for players, Miyamoto forced the player to listen to the old man who gives the player their sword, and encouraged interaction among people to share their ideas with each other to find the various hidden secrets, a new form of gaming communication. Relatedly, this concept turned into the root of another series to be developed many years in the future: "Zelda became the inspiration for something very different: Animal Crossing. This was a game based solely on communication."[33]

With The Legend of Zelda, Miyamoto wanted to flesh out the idea of a game "world" even further, giving players a "miniature garden that they can put inside their drawer."[31] He drew his inspiration from his experiences as a boy around Kyoto, where he explored nearby fields, woods, and caves, always trying through Zelda games to impart players some sense of that limitless wonder he felt through unknown exploration.[31] "When I was a child," he said, "I went hiking and found a lake. It was quite a surprise for me to stumble upon it. When I traveled around the country without a map, trying to find my way, stumbling on amazing things as I went, I realized how it felt to go on an adventure like this."[34] The memory of being lost amid the maze of sliding doors in his family's home in Sonobe was recreated in Zelda's labyrinthian dungeons.[35]

The hero “Link” was so named in part to connect players inserted into this world with their interactive role, as something of a blank slate represent and not their individuality or methods. Designed by Miyamoto as a coming of age motif to identify with, journeying as an ordinary boy strengthened by trials to triumph over great challenges and rise to meet evil.[7] The name of the titular princess came from Zelda Fitzgerald. Miyamoto explained, “Zelda was the wife of famous novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald. She was a famous and beautiful woman from all accounts, and I liked the sound of her name. So I took the liberty of using [it] for the very first title.”[36] Early Zelda concepts involved technological elements, with microchips for the Triforce made of electronic circuits and a time-travelling protagonist, another factor of their name relating to the idea of a computer hyper-”link”. While the final game follows a more traditional heroic fantasy setting, subsequent games in the series have incorporated some technology based concepts.[37]

Koji Kondo (credited as Konchan)[28] composed the game's five music tracks. He had planned to use Maurice Ravel's Boléro as the title theme, but was forced to change it late in the development cycle after learning that the copyright for the orchestral piece had not yet expired. As a result, Kondo wrote a new arrangement of the overworld theme within one day, which has become an iconic motif echoing throughout continued entries of the series.[38]

In February 1986, Nintendo released The Legend of Zelda as the launch game for the Family Computer's new Disk System peripheral, joined by a re-release of Super Mario Bros., Tennis, Baseball, Golf, Soccer, and Mahjong as part of the system’s introduction. It made full use of Disk Card media's advantages over traditional ROM cartridges, with an increased size of 128 kilobytes which would be expensive to produce on cartridge format.[31] Due to the still-limited amount of disk space, all of the text used in game was from only a single syllabary known as katakana, which under normal circumstances primarily relates more to foreign words which supplement those of traditional Japanese origin as with hiragana and kanji characters. Rather than passwords, rewritable disks saved players’ game progress, and the extra sound channel provided by the system was utilized for certain sound effects; most notably Link's sword beam at full health, roars and growls of dungeon bosses, and those of defeated enemies. Sound effects had to be altered for the eventual cartridge release version of Zelda which used the Famicom's PCM channel. The game also took advantage of that system’s controller having a built-in microphone, a feature the NES model did not include.[39] It was used to defeat the large-eared rabbit-like monster Pols Voice by blowing or shouting.[39] The U.S. instruction manual still hints that this enemy "hates loud noise", confusing many into thinking the recorder item could be used to attack. (In actuality, it has no effect.) The cartridge version made use of the Memory Management Controller chip (specifically the MMC1 model), which could use bank-switching to allow for larger games than had previously been possible, and could also use battery-powered RAM letting players save their data for the first time on any cartridge-based medium.[40]

American release

When Nintendo published the game in North America, the packaging design featured a small portion of the box cut away to reveal the unique gold-colored cartridge. In 1988, The Legend of Zelda sold two million copies.[41] Nintendo of America sought to keep its strong base of fans; anyone who purchased a game and sent in a warranty card became a member of the Fun Club, whose members got a four-, eight- and eventually 32-page newsletter. Seven hundred copies of the first issue were sent out free of charge, but the number grew as the data bank of names got larger.[42]

From the success of magazines in Japan, Nintendo knew that game tips were a valued asset. Players enjoyed the bimonthly newsletter's crossword puzzles and jokes, but game secrets were most valued. The Fun Club drew kids in by offering tips for the more complicated games, especially Zelda, with its hidden rooms, secret keys and passageways.[42] The mailing list grew. By early 1988, there were over 1 million Fun Club members, which led then-Nintendo of America president Minoru Arakawa to start the Nintendo Power magazine.[43]

Since Nintendo did not have many products, it made only a few commercials a year, meaning the quality had to be phenomenal. The budget for a single commercial could reach US $5 million, easily four or five times more than most companies spent.[44] One of the first commercials made under Bill White, director of advertising and public relations, was the market introduction for the Legend of Zelda, which received a great deal of attention in the ad industry. In it, a wiry-haired, nerdy guy (John Kassir) walks through the dark making goofy noises, yelling out the names of some enemies from the game, and screaming for Zelda.[44]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

The Legend of Zelda received highly positive reviews from critics and was a bestseller for Nintendo, selling over 6.5 million copies;[46] it was the first NES game to sell over 1 million.[47] It was reissued in 1992 as part of Nintendo's "Classic Series" and featured a grey cartridge. The game placed first in the player's poll "Top 30" in Nintendo Power's first issue[48] and continued to dominate the list into the early 1990s. The Legend of Zelda was also voted by Nintendo Power readers as the "Best Challenge" in the Nintendo Power Awards '88.[49] The magazine also listed it as the best Nintendo Entertainment System video game ever created, stating that it was fun despite its age and it showed them new ways to do things in the genre such as hidden dungeons and its various weapons.[50] GamesRadar ranked it the third best NES game ever made. The staff praised its "mix of complexity, open world design, and timeless graphics".[51]

Computer Gaming World in 1988 named the game as the best adventure of the year for Nintendo, stating that Zelda had been a "sensational success" in translating a computer RPG to consoles.[52] In 1990 the magazine stated that the game was a killer app, causing computer CRPG players who had dismissed consoles as "mere arcade toys" to buy the NES.[53] Zelda was reviewed in 1992 by Total! #2 where it received a 78% rating due in great part to mediocre subscores for music and graphics.[54] A 1993 review of the game was printed in Dragon #198 by Sandy Petersen in the "Eye of the Monitor" column. Petersen gave the game 4 out of 5 stars.[55]

The Legend of Zelda is often featured in lists of games considered the greatest or most influential. It placed first in Game Informer's list of the "Top 100 Games of All Time" and "The Top 200 Games of All Time" (in 2001 and 2009 respectively),[56][57] thirteenth in Electronic Gaming Monthly's 100th issue listing the "100 Best Games of All Time",[58] fifth in Electronic Gaming Monthly's 200th issue listing "The Greatest 200 Videogames of Their Time",[59] seventh in Nintendo Power's list of the 200 Best Nintendo Games Ever,[60] 77th in Official Nintendo Magazine's 100 greatest Nintendo games of all time[61] and 80th among IGN readers' "Top 99 Games".[62] Zelda was inducted into GameSpy's Hall of Fame in August 2000[63] and voted by GameSpy's editors as the tenth best game of all time.[64] Editors of the popular Japanese magazine Weekly Famitsu voted the game among the best on the Famicom.[65] In 1997 Next Generation listed the North American release in their "Five Greatest Game Packages of All Time", citing the die-cut hole which revealed the gold cartridge, full color manual, and fold-out map.[66]

Impact and legacy

The Legend of Zelda is considered a spiritual forerunner of the modern role-playing video game (RPG) genre.[20] Though it is often not considered part of the genre since it lacked key RPG mechanics such as experience points, it had many features in common with RPGs and served as the template for the action role-playing game genre.[67] The game's fantasy setting, musical style and action-adventure gameplay were adopted by many RPGs. Its commercial success helped lay the groundwork for involved, non-linear games in fantasy settings, such as those found in successful RPGs,[68] including Crystalis, Soul Blazer, Square's Seiken Densetsu series, Alundra, and Brave Fencer Musashi. The popularity of the game also spawned several clones trying to emulate the game.[69]

The Legend of Zelda spawned a solitary sequel, many prequels and spin-offs and is one of Nintendo's most popular series. It established important characters and environments of the Zelda universe, including Link, Princess Zelda, Ganon, Impa, and the Triforce as the power that binds Hyrule together.[31] The overworld theme and distinctive "secret found" jingle have appeared in nearly every subsequent Zelda game. The theme has also appeared in various other games featuring references to the Zelda series.

An arcade system board, called the Triforce, was developed jointly by Namco, Sega, and Nintendo, with the first games appearing in 2002. The name "Triforce" is a reference to Nintendo's The Legend of Zelda series of games, and symbolized the three companies' involvement in the project.[70]

GameSpot featured The Legend of Zelda as one of the 15 most influential games of all time, for being an early example of open world, nonlinear gameplay, and for its introduction of battery backup saving, laying the foundations for later action-adventure games like Metroid and role-playing video games like Final Fantasy, while influencing most modern games in general.[68] In 2009, Game Informer called The Legend of Zelda "no less than the greatest game of all time" on their list of "The Top 200 Games of All Time", saying that it was "ahead of its time by years if not decades".[71]

In 2011, Nintendo celebrated the game's 25th anniversary in a similar vein to the Super Mario Bros. 25th anniversary celebration the previous year.[72] This celebration included a free mailout Club Nintendo offer of the Ocarina of Time soundtrack to owners of the 3DS version of that particular game, the first digital for Nintendo eShop release of Link's Awakening DX, special posters that are mailed out as rewards through Club Nintendo, and a special stage inspired by the original Legend of Zelda in the video game Super Mario 3D Land for the Nintendo 3DS.

Re-releases

The Legend of Zelda was first re-released in cartridge format for the Famicom in 1994.[4] The cartridge version slightly modified the title screen of the Disk Card version of the game, such that it displayed the number 1 at the end of the title. In 2001, the original game was re-released in the GameCube game Animal Crossing. The only way to unlock the game is by using an Action Replay. An official re-release was included in 2003's The Legend of Zelda: Collector's Edition for the GameCube,[73] and the game was again re-released on the Game Boy Advance in 2004 along with its sequel, The Adventure of Link, as part of the Famicom Mini/Classic NES Series. In 2006, it was released on the Wii's Virtual Console, and a timed demo of the game was released for the 2008 Wii game Super Smash Bros. Brawl, available in the Vault section.

All re-releases of the game are virtually identical to the original, though the GameCube, Game Boy Advance, and Virtual Console versions have been altered slightly to correct several instances of incorrect spelling from the original, most notably in the intro story. A tech demo called Classic Games was shown for the Nintendo 3DS at E3 2010, showcasing more than a dozen classic games using 3D effects, including The Legend of Zelda.[74] It was announced by Reggie Fils-Aimé, president of Nintendo of America, that the games were slated for release on the 3DS, including The Legend of Zelda, Mega Man 2, and Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island and would possibly make use of some of the 3DS's features, such as 3D effects, analog control, or camera support.[75]

The Legend of Zelda was released to the Nintendo 3DS Virtual Console on September 1, 2011 as a part of the Nintendo 3DS Ambassador program, and was later released to the Nintendo 3DS eShop on December 22, 2011 in Japan, April 12, 2012 in Europe and July 5, 2012 in North America.[76][77] The game was released for the Nintendo Switch as part of the Nintendo Switch Online - Nintendo Entertainment System service on September 18, 2018. A special "Living the life of luxury!" edition of the game, which grants players all equipment and extra items at the start of the game, was added to the service on October 10, 2018.[78]

Sequels

There have also been a few substantially altered versions of the game that have been released as pseudo-sequels, and ura- or gaiden-versions. As part of a promotional advertisement campaign for their charumera (チャルメラ) noodles, Myojo Foods Co., Ltd. (明星食品, Myoujou Shokuhin) released a version of the original The Legend of Zelda in 1986,[79] Zelda no Densetsu: Teikyō Charumera (ゼルダの伝説 提供 チャルメラ).[80][81] It is one of the rarest video games available on the second-hand collector's market, and copies have sold for over US$1,000.[82]

From August 6, 1995, to September 2, 1995,[83] Nintendo, in collaboration with the St.GIGA satellite radio network, began broadcasts of a substantially different version of the original The Hyrule Fantasy: Legend of Zelda for a Super Famicom peripheral, the Satellaview—a satellite modem add-on. The game, BS Zelda no Densetsu (BS ゼルダの伝説), was released for download in four episodic, weekly installments which were rebroadcast at least four times between the game's 1995 premier and January 1997. BS Zelda was the first Satellaview game to feature a "SoundLink" soundtrack—a streaming audio track through which, every few minutes, players were cautioned to listen carefully as a voice actor narrator, broadcasting live from the St.GIGA studio, would give them plot and gameplay clues.[84] In addition to the SoundLink elements, BS Zelda also featured updated 16-bit graphics, a smaller overworld, and different dungeons. Link was replaced by one of the two Satellaview avatars: a boy wearing a backward baseball cap or a girl with red hair.

Between December 30, 1995, and January 6, 1996,[85] a second version of the game, BS Zelda no Densetsu MAP 2 (BS ゼルダの伝説MAP2), was broadcast to the Satellaview as the functional equivalent of the original The Legend of Zelda's Second Quest. MAP 2 was rebroadcast only once, in March 1996.[83]

Notes

- Reported dates for US release varies; sources either state it was released in July 1987[3][4][5] or on 22 August 1987[6]

- Originally released in Japan as Legend of Zelda: The Hyrule Fantasy (Japanese: ゼルダの伝説 THE HYRULE FANTASY, Hepburn: Zeruda no Densetsu Za Hairaru Fantajī)

- In Japanese: THE HYRULE FANTASY ゼルダの伝説1 (Zelda no Densetsu 1)

References

- "Proto:The Legend of Zelda". tcrf.net.

- "照井啓司さんのコメントコーナー" (in Japanese). Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- "The Legend of Zelda - NES". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- "The Legend of Zelda". NinDB. Archived from the original on 2010-06-19. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- "NES Games" (PDF). Nintendo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- "The Legend of Zelda". GameSpot. CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- "Shigeru Miyamoto Interview". Super PLAY (in Swedish). Medströms Dataförlag AB (4/03). March 2003. Archived from the original on September 7, 2006. Retrieved 24 Sep 2006.

- The Legend of Zelda Instruction Booklet. Nintendo of America, Inc. pp. 3–4.

- The Legend of Zelda Instruction Booklet. Nintendo of America, Inc. p. 18.

- "放課後のクラブ活動のように". 社長が訊く. Nintendo Co., Ltd. 19 November 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

1986年2月に、ファミコンのディスクシステムと同時発売された、アクションアドベンチャーゲーム。 / An action-adventure game simultaneously released with the Famicom Disk System in February 1986.

- Gerstmann, Jeff (22 November 2006). "The Legend of Zelda Review". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- "The Legend of Zelda: Collector's Edition". GameSpot. CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- "The Legend of Zelda - Wii". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- The Legend of Zelda Instruction Booklet. Nintendo. p. 41.

- The Legend of Zelda Instruction Booklet. Nintendo of America, Inc. p. 28.

- The Legend of Zelda Instruction Booklet. Nintendo of America, Inc. pp. 29–31.

- The Legend of Zelda Instruction Booklet. Nintendo of America, Inc. pp. 32–39.

- The Legend of Zelda Instruction Booklet. Nintendo. pp. 21–26.

- deWinter, Jennifer (2015). Shigeru Miyamoto: Super Mario Bros., Donkey Kong, The Legend of Zelda. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-6289-2386-5.

- Andrew Long. "The Legend of Zelda — Retroview". RPGamer. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- "Zelda Handheld History". Iwata Asks. Nintendo. 26 January 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- "『裏ゼルダ』の裏話". 社長が訊く. Nintendo. 19 November 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ZELDA: The Second Quest Begins (1988), p. 28

- No byline. "IGN: The Legend of Zelda Cheats, Codes, Hints & Secrets for NES". Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- The Legend of Zelda Encyclopedia. Dark Horse. 2018. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-1-50670-638-2.

- The Legend of Zelda Instruction Booklet. Nintendo of America, Inc. p. 39.

- The Legend of Zelda Instruction Booklet. Nintendo. p. 10.

- Nintendo Co., Ltd (August 22, 1987). The Legend of Zelda. Nintendo of America, Inc. Scene: staff credits.

- "Classic: Zelda und Link". Club Nintendo (in German). Nintendo: 72. April 1996.

- Legend of Zelda Developer Interview with Shigeru Miyamoto, Legend of Zelda: Sound and Drama, 1994

- Vestal, Andrew; Cliff O'Neill; Brad Shoemaker (2000-11-14). "History of Zelda". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2006-07-01. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- Bufton, Ben (2005-01-01). "Shigeru Miyamoto Interview". ntsc-uk. Retrieved 2006-09-23.

- Miyamoto, Shigeru (8 March 2007). Creative Visions (Speech). Game Developers Conference (in Japanese).

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Sheff (1993), p. 51

- Sheff (1993), p. 52

- Mowatt, Todd. "In the Game: Nintendo's Shigeru Miyamoto". Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- Miyamoto, Shigeru; Trinen, Bill (2016-06-18). "Interview Miyamoto : "Un équilibre difficile à trouver"". Gamekult (Interview) (in French). Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- MacDonald, Mark (May 3, 2005). "Zelda Exposed from 1UP.com". 1UP.com. IGN. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- Edwards, Benj (2008-08-07). "Inside Nintendo's Classic Game Console (slide 7)". PC World. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- "Why Your Game Paks Never Forget", Nintendo Power, Nintendo (20), pp. 28–31, January 1991

- Sheff (1993), p. 172

- Sheff (1987), p. 178

- Sheff (1993), p. 178

- Sheff (1993), p. 188

- Marriott, Scott Alan. "The Legend of Zelda - Overview". Allgame. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- "March 25, 2004". The Magic Box. 2004-03-25. Archived from the original on 2005-11-26. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- "Narly Nintendo – The Duffer's Guide to Nintendomania". Raze. Newsfield Publications (5): 18. March 1991.

- "Top 30", Nintendo Power, 1, p. 102, July–August 1988

- "Nester Awards", Nintendo Power, Nintendo (6), pp. 18–21, May–June 1989

- "Nintendo Power — The 20th Anniversary Issue!" (Magazine). Nintendo Power. 231 (231). San Francisco, California: Future US. August 2008: 71. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Best NES Games of all time". GamesRadar. 2012-04-16. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- Kunkel, Bill; Worley, Joyce; Katz, Arnie (November 1988). "Video Gaming World". Computer Gaming World. p. 54.

- Adams, Roe R. III (November 1990). "Westward Ho! (Toward Japan, That Is)". Computer Gaming World. p. 83. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Jarratt, Steve. The Legend of Zelda. Total!. Issue 2. Pg.20-21. February 1992.

- Petersen, Sandy (October 1993). "Eye of the Monitor". Dragon (198): 57–60.

- Cork, Jeff (2009-11-16). "Game Informer's Top 100 Games of All Time (Circa Issue 100)". Game Informer. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- Game Informer staff (December 2009). "The Top 200 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 200. pp. 44–79.

- "100 Best Games of All Time". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 100. Ziff Davis. November 1997. p. 152. Note: Contrary to the title, the intro to the article (on page 100) explicitly states that the list covers console video games only, meaning PC games and arcade games were not eligible.

- S.B. (February 2006). "The 200 Greatest Video Games of their Time". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Archived from the original on 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- "NP Top 200", Nintendo Power, 200, pp. 58–66, February 2006

- "80-61 ONM". ONM. Archived from the original on April 1, 2011. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- "Readers' Picks Top 99 Games: 80-71". IGN. April 11, 2005. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- Buecheler, Christopher (August 2000). "The Gamespy Hall of Fame". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 2006-08-19. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- GameSpy Staff (July 2001). "GameSpy's Top 50 Games of All Time". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 2008-03-20. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- taragan (2006). "Famitsu Readers' All-time Favorite Famicom Games". Pink Godzilla. Archived from the original on 2008-06-17. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- "The Five Greatest Game Packages of All Time". Next Generation. No. 32. Imagine Media. August 1997. p. 38.

- "GameSpy's 30 Most Influential People in Gaming". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- "15 Most Influential Games of All Time: The Legend of Zelda". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2010-05-15. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- An example is a clone for the TRS-80 Color Computer III called "The Quest for Thelda", written by Eric A. Wolf and licensed to Sundog Systems."Quest For Thelda". 2003-10-06. Archived from the original on 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- "Namco Triforce Hardware". System16. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- The Game Informer staff (December 2009). "The Top 200 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 200. pp. 44–79. ISSN 1067-6392. OCLC 27315596.

- "Zelda 25th anniversary will be special — Nintendo". Official Nintendo Magazine. 8 March 2010. Archived from the original on March 9, 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- IGN Staff (2003-10-06). "True Zelda Love". IGN. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- Harris, Craig (June 15, 2010). "E3 2010: Classic NES in 3D!". IGN. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- Jackson, Mike (21 June 2010). "News: SNES, NES classics set for 3DS return". ComputerAndVideoGames.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- "The Legend of Zelda". GameFAQs. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- "The Legend of Zelda 3DS". Nintendo. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- "A New Version of the Legend of Zelda Just Launched on Switch".

- Keef. ファミコン ディスクシステム Archived 2011-07-13 at the Wayback Machine. Urban Awakening DiX (覚醒都市DiX). Yuri Sakazaki Museum. 2009.

- Kahf, A. ファミコン非売品リスト Archived April 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. No Enemy in Our Way! Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- Day, Ashley. The Ultimate Guide To... #06 The Legend of Zelda: The Versions of Zelda - Zelda no Densetsu: Teikyou Charumera (1986). Retro Gamer. Issue 90. Pg.62. May 2011.

- The Rarest and Most Valuable NES Games Archived November 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Digital Press (via RacketBoy). 25 May 2010.

- Kameb (2008-02-12). かべ新聞ニュース閲覧室 (in Japanese). The Satellaview History Museum. Archived from the original on 2011-02-04. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- "BS The Legend of Zelda". IGN. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- Kameb (2008-02-12). サウンドリンクゲーム一覧 (in Japanese). The Satellaview History Museum. Archived from the original on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- Sheff, David (1993). Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children. Random House. ISBN 0-679-40469-4.

- "ZELDA: The Second Quest Begins", Nintendo Power, 1, pp. 26–36, July–August 1988