The Kirna

The Kirna, known locally as Kirna House (previously Grangehill), is a Category A listed villa in Walkerburn, Peeblesshire, Scotland.[1] It is one of four villas in Walkerburn designed by Frederick Thomas Pilkington between 1867-69 for the Ballantyne family.[2] It is listed as a fine example of a Pilkington mansion retaining original external features, a fine interior, and for its importance as a Ballantyne property.

| The Kirna | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Walkerburn, Scotland |

| Nearest city | Edinburgh |

| Coordinates | 55°37′34″N 3°01′57″W |

| Elevation | 180m |

| Built | 1867 |

| Built for | George Ballantyne |

| Architect | Frederick Thomas Pilkington |

| Architectural style(s) | Scots Baronial, High Victorian Gothic, Ruskinian Gothic, Venetian Romanesque |

| Owner | Alan & Desa Facey |

| Website | kirna |

Listed Building – Category A | |

| Official name: The Kirna | |

| Designated | 22 July 1985 |

| Reference no. | 8323 |

Location in the Scottish Borders | |

The Ballantyne family played a leading role in Scotland's textile industry for nearly two hundred years.[3] The Ballantynes were substantially responsible for founding the village of Walkerburn after Henry Ballantyne first bought land at that location to build a tweed mill in 1846. Renowned architect F T Pilkington was commissioned by the Ballantynes to design and build the new village with houses for the mill workers, The Kirna, and other villas for the Ballantyne family.[4] [5]

The Kirna's proximity to a significant number of man-made structures, including some dating back to pre-historic times, suggests that this general location along the Tweed valley has been of strategic importance to settlers throughout history.

Design & Architecture

The Kirna retains all of its original 1867 Scots Baronial and Venetian Romanesque design features including an idiosyncratic tower in Ruskinian Gothic style.[6] The heavy oak main staircase features distinctive turned and carved balusters also found in F T Pilkington's own house, Egremont, 38 Dick Place, Edinburgh, and grotesque finials holding shields sporting the initials of George Ballantyne and his wife Marion White Aitken (1841-1914). [1] [7]The dining room ceiling incorporates the initials of Colin Ballantyne and his wife Isabella Milne Welsh (1881-1969), respectively.[8]

Of special architectural note is the main entrance and heavily decorated (sculpted) elevation featuring a central flight of ashlar steps leading to a polygonal, arcaded loggia entrance area which is supported by two rope-moulded arches. Immediately above the entrance is the first floor with prominent chequered detail between the band courses, and a repeat of the rope moulding around the windows. The second floor features a turret with two finialled dormers. The Kirna shares many of these design elements with another F T Pilkington building originally known as Craigend Park in Edinburgh, designed and built for William Christie between 1866 and 1869, a "Glover and Breeches Maker" (tailor) at 16 George Street who is believed to have sourced much of his material from the Ballantyne mills.[9]

Designs of The Kirna were exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy in 1867. The subsequent review in The Builder noted that "Pilkington is never commonplace, though frequently wild and eccentric". The Kirna was praised as "a pleasing example of the modern style Gothic as applied to domestic purposes: abundance of light is given, and variety is secured without violent contrast".[10]

Drawings of alterations dated 1903 by James Jerdan (architect at 12 Castle Street, Edinburgh), indicate the addition of a coal chute and "heating chamber" area located beside the main building.[11] An innovative tunnel from the heating chamber to the basement area permitted staff to transport coal to the core of the house without disturbing the proprietor. The 1903 alterations included the addition of a 'boudoir' (now game room) to the west gable, and a bedroom on the first floor.

The boundary wall and a glass house still survive. The entrance gates were likely removed during the war in 1941 when the government passed an order compulsorily requisitioning all post-1850 iron gates and railings for the war effort.[12]

History

Ownership

The Kirna was built in 1867 for George Ballantyne (1836-1924), third son of Henry Ballantyne (1802-1865). George acquired the site from Alexander Horsburgh of Horsburgh in 1867 after having built the boundary walls, driveway, and some or all of the house. The deed explicitly provided for George to draw his domestic water from the Kirna Burn until such time as a reservoir was constructed to supply the Estate of Pirn, and to source stone from Purveshill quarries.[13] He and his family owned and occupied The Kirna between 1867 and 1880 when, curiously, he sold the property to his brother David Ballantyne (1825-1912).[14]

Marian Currie (née Upwood), widow of Charles Currie (1829-1878, son of Sir Frederick Currie, 1st Baronet), acquired the property in 1888 and remained at The Kirna until just before she died in 1903 and the property was sold to Katherine "Kitty" Hamilton Bruce, widow of Robert Hamilton Bruce, a successful Glasgow businessman, and daughter of Simon Somerville (Tae) Laurie, a Scottish educator.[15][16] Kitty owned The Kirna for sixteen years before selling to Colin Ballantyne (1879-1942), son of John Ballantyne (1829-1909), in 1919. Colin Ballantyne continued to own the property until just before his death in 1942.[17] He was the third and final member of the Ballantyne family to have owned The Kirna.

Between 1941 and 1992 The Kirna was owned by respectively Emily Skinner (1941-48), James Forbes (1948-53), Winnifred and Henry Pearson Taylor Smith (1953-57),[18] Peter Rodger (1957-59), James Fraser (1959-81), John Rapley (1981-91), and briefly by Peter Hammond (1991-92).[19]

Julian Osborne, solicitor, purchased The Kirna in 1992.[20] It was acquired by the Facey family in 2018.

George, The Kirna, and New Zealand

Between 1870 and 1872 George secured two personal loans amounting to £800 (£95,000 in 2019)[note 1] using The Kirna as collateral, suggesting that he may have been facing financial difficulties. George advertised The Kirna for sale in April of 1871 after the death of his three-year-old son Henry George Tait, and when it did not sell he advertised it to let, furnished, by the year.[21] In 1874 he mortgaged The Kirna for £1,000 (£120,000 in 2019) and used a portion of the proceeds to repay £500 of his outstanding personal loans. In 1878 The Kirna was put up for auction in Peebles but it did not sell.[22] The remainder of his personal loan amount was repaid in 1879.

George sold The Kirna to his brother David for £2,100 (£250,000 in 2019) when he emigrated to New Zealand in 1880, notionally to enter the wool-buying business to supply the requirements of Henry Ballantyne's mills.[23][24] David already owned a property (Sunnybrae) in Walkerburn at that time, suggesting that his purchase of The Kirna was designed to facilitate George's departure and possibly his exit from Henry Ballantyne's business. George used the proceeds of the sale to discharge his £1,000 mortgage. David let The Kirna, fully furnished, until 1888 when he auctioned off the furniture and sold the property.[25]

Not long after his arrival in New Zealand, and despite his original mandate, George accepted a position as manager of the newly-formed Oamaru Woollen Factory Company in 1881.[26] He went to Britain and selected the plant for the new factory, had the plans for the mill drawn up, and engaged key staff. He was dismissed in May 1883 for performance reasons and put up for auction 1000 of his shares in the factory in May of 1884.[27][28] George is also known to have held a management role at the North New Zealand Woollen Manufacturing Company in Onehunga, Auckland in 1886.[29] There is no record of George engaging with Henry Ballantyne's mills after 1881.

George died in 1924 in New Zealand. His estate was valued at £120 (£7,000 in 2019).[30]

Coach House

The Kirna was built in 1867 with a separate stable block and coach house rather than a traditional entrance lodge. In 1923, architect William James Walker Todd made alterations to the stable and coach house for Colin Ballantyne, including converting a section of the stable to a (second) bedroom and a bathroom.[31][32]

The Kirna and the coach house were formally separated in 1948 when Emily Skinner sold The Kirna to James Forbes who immediately sold the coach house to William Johnson, an architect from Edinburgh.[33]

Property Name

At various times The Kirna has also been referred to as Kirnie House or Kirna House. All three names are an obvious connection to its location at the base of Kirnie Law hill and to nearby Kirnie Tower (see below).

Ordnance Survey Name Books for the parish of Innerleithen written prior to the construction of The Kirna cite a "one storey house" named Kirnie, property of the Horsburgh family, situated at or near the current site of The Kirna. 1841, 1851 and 1861 Census data refer to a shepherd named James Tait and his family living at Kirna (or Kirnie).[34] The building cited is almost certainly the house currently known as Kirna Cottage (see below).[35] Ordnance Survey historical maps published in 1897, 1898 and 1909 record the property as Kirnie House.[36]

Between 1903 and 1919 when it was sold to Colin Ballantyne, The Kirna was known as Grangehill.[37][38] The owner at that time, Katherine Bruce, is known to have resided at The Grange in Dornoch and at Grange Dell in Penicuik, demonstrating a predilection for names including 'Grange'.[39]

The current name, Kirna House, may have come about when the Post Office needed to be able to distinguish between the villa and the coach house (now Kirna Lodge) when the latter was sold as a separate property in 1948.[33]

Kirna 'Firsts'

Colin Ballantyne would have been the first proprietor of The Kirna to have enjoyed a candlestick telephone with subscriber number 16. He could reach his mother at Stoneyhill on number 12, his brother John King Ballantyne at Nether Caberston [note 2]on number 3, his cousin John Alexander at Sunnybrae on number 14, and the Walkerburn Co-operative Society on number 4, amongst others.[40] The first telephones were installed in Walkerburn in 1891 and by the 1920s the village had approximately ten telephone subscribers, likely connected by a small manual exchange tended by a caretaker operator. [41]

At some time prior to 1878 the house was tied in to the Peebles (Eshiels) gas works and some or all of the fireplaces at The Kirna we converted to gas-fired.[42] The first gas street lamps were installed in Walkerburn in 1878.

Central heating was first installed in approximately 1993. The Kirna was originally designed and built with nine open fireplaces. The alterations of 1903 added a further four fireplaces and an oil-fired hot water boiler in the newly constructed "heating chamber".

Location

The Kirna is situated on Peebles Road (A72), originally Pink Bank, in the valley of the River Tweed, a few hundred meters west of Walkerburn village. Peebles Road was the turnpike road between Galashiels and Peebles which was constructed in circa 1775.[43]

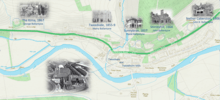

The property is unusual as it stands away from the other three Ballantyne family houses designed by F T Pilkington in Walkerburn (John Ballantyne's house Stoneyhill, David's house Sunnybrae and Henry's former home Tweedvale) but exhibits features found on the other buildings.[44][45][46][47] Other Ballantyne villas in the vicinity during this era included Holylee owned by Major James George Ballantyne (1837-1884), and The Firs (Horsbrugh Terrace, Innerleithen) owned by James Ballantyne (1839-1903). [48][49]

The Kirna is in close proximity to almost a dozen man-made structures, some dating back to pre-historic times, illustrating the strategic importance of this location to settlers throughout history. The site and surrounding lands benefit from ample supplies of fresh water from the Kirna Burn and the Walker Burn, its elevation above the flood plain of the Tweed River, extensive views up and down the Tweed Valley, the south-facing slope of Kirnie Law, and a rich topsoil.[50]

Mid-19th century maps indicate an old whinstone quarry approximately 30 meters beyond the northwest corner of the boundary wall and in the path of the Kirna Burn that travels along the west boundary wall from Kirnie Law to the Tweed river.[50][51]

Nearby Historic Structures

Kirna Burn Water Tank

.jpg)

A for sale advertisement in The Scotsman published on April 15, 1871 cites "an abundance of beautiful spring water" to The Kirna. It is likely that the water tank positioned upstream from The Kirna on Kirna Burn provided that source of fresh water from 1867 until at least 1961 despite local authorities being required by law to provide water to communities from the 1940s.[52][53] It is unclear whether this particular tank functioned as an intake or a storage tank.

Kirnie Law Reservoir

The Kirna is due south of Kirnie Law Reservoir which was built to provide hydro-electric power for Tweedvale Mill and Tweedholm Mill in Walkerburn, owned by Henry Ballantyne & Sons, Ltd. The project was conceived of and designed by Boving & Co. Ltd. (hydraulic engineers) and became operational in 1922.[54][55] This was the first working hydro-electric power scheme in the country.[56] The reservoir continued in use until around 1950.[57]

The ferro-concrete reservoir is still substantially intact. Its interior measures 58.5 meters squared by 4.7 meters deep and the walls are 20 centimeters at the top tapering to 35 centimeters at the base. The tank was capable of holding 13.2 million liters of water. There is a surge tank (pumping station) downhill that controlled the water flow to the turbines in the valley.[58][59][60]

Prehistoric Enclosure

Located approximately 270 meters NW of The Kirna is a prehistoric enclosure (settlement). It is recorded as an 'ancient monument forming part of the lands of Caberston' under the Ancient Monuments Act, 1931. The settlement has been mostly destroyed by cultivation, stone-robbing, and the construction of a semi-circular sheepfold, now in ruins. However, sufficient remains to show that it measured about 50 meters N-S by slightly less transversely, and that it was originally enclosed by a wall.[61][62]

Ancient Terraces and Tower

.jpg)

The remains of ancient terraces and Purvishill Tower are located approximately 200 meters due west of The Kirna at the base of Purvis Hill. Although they are technically of unknown origin, it is believed that the terraces belong to the Pictish period (600-700AD). Given their unusual scale, character and location, the terraces may have been intended to provide level ground for gardens or orchards, although a more utilitarian agricultural function is also possible.[63]

Kirnie Tower

Approximately 80 meters to the south of The Kirna, across the A72, is the site of Kirnie Tower. Its site was pointed out in 1856 by residents of Walkerburn who were present at its removal in circa 1840 when its stones were removed for building purposes elsewhere on the Horsburgh estate. Long after its dismantlement it was used as a shepherd's hut.[35] Maps published as far back as 1654 refer to "Kirn" or "Kirna" in approximately the location of Kirnie Tower.[64] Ordnance Survey Name Books in the mid-1800s record the structure as "one of the ancient feudal residences erected for the protection of the Borders. It was square in appearance".[65][66][35]

A series of these peel towers was built in the 15th century along the Tweed valley from its source to Berwick, as early-warning beacons announcing invasion from the Marches.[67][68][69]

Romano-British Settlement

A scooped homestead, measuring 26x23 meters internally, is situated on the steep SW face of Purvis Hill, approximately 200 meters north of The Kirna. The enclosing wall has been largely lost, but the position of the entrance is still visible. Within the walls is a platform large enough to support two timber houses.[70]

Kirnie Cottage

It is believed that the cottage, locally known as Kirnie Cottage, situated just outside and to the west of the boundary wall of The Kirna on the A72 was the shepherd's cottage for Pirn House (demolished in early 1950s) built by Stirling & Son of Galashiels when they were building the mill houses in Walkerburn for "Captain" Horsburgh.[71][72] It has also been variously tagged as Kirna or Kirnie Toll House, however this seems unlikely given the nearby turnpike toll house (est. 1830) in Innerleithen.[73][74] Kirnie Cottage was notoriously put up for sale in 2011 by a squatter who tried to sell the cottage for £70,000 without the knowledge of the owner.[75][76]

Kirna Lodge

Kirna Lodge is located within the original boundary walls of The Kirna. It started life as the stable and coach house for The Kirna. Today, Kirna Lodge is a three-bedroom house overlooking the Tweed Valley, with a conservatory and a four-car garage. The kitchen is now in what used to be the stable in 1923. The original coach house has made way for a principal bedroom and, more recently, a general purpose room.

The lodge exhibits a flush bracket (OSBM G293) that was used during the Second Geodetic Leveling of Scotland that took place between 1936 and 1952, and was leveled with a height of 157.0421 meters [note 3]above mean sea level.[77][78] This bracket was included on the Innerleithen to Duns Common leveling line.

Notes

- 2019 equivalent based on CPI

- now known as Windlestraw, built in 1906

- Ordnance Datum Newlyn

References

- "THE KIRNA, B8323". Historic Environment Scotland. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- "DSA Architect Biography Report: F T Pilkington". Dictionary of Scottish Architects 1660-1980. Archived from the original on 2018-12-14. Retrieved 2018-12-14.

- "Robert Noble: Timeline". Robert Noble. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Gulvin, Clifford (1973). The tweedmakers; a history of the Scottish fancy woollen industry 1600-1914. New York: Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

- Keay, John; Keay, Julia (1994). Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. HarperCollins. p. 776.

- Turner, Jane (1996). The dictionary of art - Vol. 24. New York, NY: Grove's Dictionaries, Inc. p. 810. ISBN 1-884446-00-0.

- "Egremont: Interior detailed view of the carving on the balustrade of the first floor staircase". Historic Environment Scotland, Canmore. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- Royal Scottish Academy (1991). The Royal Scottish Academy exhibitors 1826-1990 : a dictionary of artists and their work in the annual exhibitions of the Royal Scottish Academy. Vol. 1, A-D. Vol. 2, E-K. Vol. 3, L-R. Vol. 4, R-Z. Hilmarton Manor Press. p. 476. ISBN 0904722228.

- "Craigend Park, Kingston Lodge, LB49540". Historic Environment Scotland. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- "Architecture in the Royal Scottish Academy". The Builder. XXV (1257): 167. 9 March 1867. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "DSA Architect Biography Report: James Jerdan". Dictionary of Scottish Architects 1660-1980. Archived from the original on 2019-02-09. Retrieved 2019-02-07.

- "Requisitioned Railings,13 July 1943 vol 128 cc437-46". Parliament.uk. Hansard. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "Feu Disposition". Registers of Scotland: General Register of Sasines. CSN 19/102378: Folio 104-113. 3 September 1867.

- Walkerburn, Its Origins and Progress 1854-1987. Edinburgh: Phillans& Wlson Greenway. 1988. p. 3.

- "Hamilton Bruce family photograph". Dornoch Historylinks. Dornoch Historylinks Museum. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- "Katherine (Kitty/Kate) Ann Laurie". Links - Genealogy. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- "Find A Grave Memorial no. 176940060". Find a Grave. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- "Trust Deed for behoof of creditors" (17271). United Kingdom Government. HMSO. 25 March 1955. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- "Search property information". Registers of Scotland. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- McLuckie, Kirsty (23 March 2017). "A Borders gem with a dash of gothic romance". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Board, Lodgings to Let" (8686). The Scotsman. 31 May 1871.

- "Heritable Property for Sale" (10753). The Scotsman. 5 Jan 1878.

- "Arrivals and Departures for the Week; Passengers for Otago" (1495). Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago Witness. 10 July 1880. p. 15. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- Gulvin, MA, PhD, Clifford (1973). The Tweedmakers; a history of the Scottish fancy woollen industry 1600-1914. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. p. 116. ISBN 0715359738.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Sales by Auction" (13965). The Scotsman. 10 April 1888.

- Roberts, W.H.S. (1890). The History of Oamaru and North Otago, New Zealand, from 1853 to the end of 1889. Oamaru: Andrew Fraser. p. 370. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Oamaru Woollen Factory (Former)". Heritage New Zealand. New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- "Advertisements, Column 3" (1322). Oamaru Mail. 2 May 1884.

- "North New Zealand Woollen Manufacturing Company (Limited)" (78). The Auckland Evening Star. 27 March 1886. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "National Records of Scotland". National Probate Index (Calendar of Confirmations and Inventories). 1876-1936: B8.

- "DSA Architect Biography Report: J W Todd". Dictionary of Scottish Architects 1660-1980. Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-12-14.

- "DSA Building/Design Report: Kirna". Dictionary of Scottish Architects 1660-1980. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- "Last page, "Plan" of disposition transferring Kirna Lodge on 24.04.1948 to W H Johnson" (PDF). Wikimedia. Registers of Scotland. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Innerleithen Parish, 1851 Census, Book 5. 30 March 1851. p. 2.

- "Peeblesshire OS Name Books, 1856-1858 Peeblesshire volume 17 OS1/24/17/45". Scotlands Places. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- "National Library of Scotland - Map Images (December 27, 2018, 2:40 pm)". maps.nls.uk. Archived from the original on December 27, 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- General Register of Sasines. Registers of Scotland. 12 May 1987.

- "Letters to the Editor". The Spectator (4252): 16. 25 December 1909. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Robert Hamilton Bruce". HistoryLinks. Dornoch Heritage SCIO. Archived from the original on 8 November 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- "Edinburgh & Leith Post Office Directory 1925-26 (page 1783)". archive.org. Postmaster General, Edinburgh. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Johnston, S.F. (2009). Scottish life and society : a compendium of Scottish ethnology. Volume 8, Transport and communications. John Donald in association with the European Ethnological Research Centre. p. 6. ISBN 9781904607885.

- "The Scotsman, January 5th 1878, Page 5". The Scotsman Digital Archive. Johnston Publishing Ltd. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Paths around Innerleithen and Walkerburn". Scottish Borders Council. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- "STONEYHILL HOUSE, STABLES AND BOUNDARY WALLS LB12930". Historic Environment Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "SUNNYBRAE HOUSE LB49135". Historic Environment Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "TWEEDVALE HOUSE LB49138". Historic Environment Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Walkerburn, Peeblesshire, Scotland (incl. photos of Ballantyne villas)". flickr. Scottish Indexes. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Royal Manual of the Titled and Untitled Aristocracy of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. London, England: Chatto and Windus. 1899. p. 339.

- Slater's (late Pigot & Co.'s) Royal national commercial directory and topography of Scotland (PDF). Slater, I. (Isaac). 1878. p. 372. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Ordnance Survey, Six-inch 1st edition, 1843-1882, Peebles-shire, Sheet XIV". National Library of Scotland. Ordnance Survey. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Reconstituted County Council for the County of Peebles (14587 ed.). Edinburgh: The Edinburgh Gazette. 1923-10-01. p. 1134. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "County of Peebles and Burghs of Peebles and Innerleithen". Annual Report by the Medical Officer of Health and County Sanitary Inspector: 58. 1961.

- "Structure of the UK Water Industry: Scotland". Sewerage Rehabilitation Manual (SRM). Water Research Centre. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- "The Evolution of a Water Power Scheme, 1854-1921" (PDF). Wikimedia. Henry Ballantyne & Sons, Limited. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- "Kirnie Law Reservoir and Surge Tower". British Listed Buildings. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Pearce, F W. Walkerburn, Its Origins and Progress, 1854-1987. Edinburgh: Pillians & Wilson Greenaway. p. 2.

- "Kirnie Law, Reservoir". Historic Environment Scotland, Canmore. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- "Kirnie Law, Reservoir, Surge Tower". Historic Environment Scotland, Canmore. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- "A Water Power Mechanical Storage Installation". Engineering and Contracting. LVII: 290-291. 4 January 1922. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- "The Mechanical Storage of Water Power". The Electrical Review. 90 (2311): 326-330. 10 March 1922. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- General Register of Sasines, Book 301. County of Peebles: Registers of Scotland. 30 October 1970. p. 26.

- "Record of a pre-historic site NW of The Kirna" (PDF). Wikimedia. Registers of Scotland. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- "Purvishill Tower, cultivation terraces, enclosure and tower (SM2391)". Historic Environment Scotland. Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Map of Innerleithen Area, 1654". National Library of Scotland. Blaeu Atlas of Scotland, 1654. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Peeblesshire: an inventory of the ancient monuments. RCAHMS. 1967. p. 237.

- Coventry, M (2008). Castles of the Clans: the strongholds and seats of 750 Scottish families and clans. Musselburgh. p. 316.

- Pennecuik, Esq., Alexander. "The Works of Alexander Pennecuik containing the Description of Tweeddale, 1815" (PDF). Google eBooks (free). A. Constable & Co, Edinburgh. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "Elibank Castle". Historic Environment Scotland, Canmore. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Maxwell-Irving, FSA, FSAScot., Alastair (2011–2012). "How Many Tower-houses were there in the Scottish Borders?" (PDF). The Castle Studies Group Journal. Castle Studies Group. 25: 224–240. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-03. Retrieved 2019-05-11.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Purvis Hill, Scooped Settlement". Historic Environment Scotland, Canmore. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- "Tweeddale's History: The Bard among guests at Pirn House". Peeblesshire News. 7 May 2017. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "Pirn House". Historic Environment Scotland, Canmore. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "MaxwellAncestry: Kirna or Kirnie Toll House, Innerleithen". flickr. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "NT3336 : The Toll House, Innerleithen". Geograph. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Walkerburn squatter's cottage sale bid ends in failure" (12 November 2012). BBC. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- "Squatter tried to sell Peebleshire house for £70k". ITV. 8 January 2013. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- "G0293 - The Kirna". flickr.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Bench Mark Database: Flush Bracket OSBM G293: Kirna Lodge". bench-marks.org.uk. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Kirna. |

- Scotland Places: Walkerburn, The Kirna

- British Listed Buildings: Walkerburn, The Kirna

- Registers of Scotland: General Register of Sasines

Further reading

- Cruft, Kitty, Dunbar, John and Fawcett, Richard. “Borders (The Buildings of Scotland)" (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006) (pp 742)

- Strang, Charles Alexander. “Borders and Berwick: Illustrated Architectural Guide to the Scottish Borders and Tweed Valley” (Rutland Press, 1994) (pp 222-223)

- Robert Ian Turner. "Frederick Thomas Pilkington (1832 - 1898), His Influences and His Legacy" (1992, Edinburgh University)

- T M Jeffery, "The Life and Works of Frederick Thomas Pilkington, Vol 1" (1981, Newcastle School of Architecture)

- F W Pearce. "Walkerburn, Its Origins and Progress 1854-1987" (undated, Pillians & Wilson Greenway) (pp 26, 73)

- Alex F Young. "Old Innerleithen, Walkerburn and Traquair" (undated, Stenlake Publishing)