The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test is a nonfiction book by Tom Wolfe that was published in 1968.[2] The book is remembered today as an early – and arguably the most popular – example of the growing literary style called New Journalism. Wolfe presents an as-if-firsthand account of the experiences of Ken Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters, who traveled across the country in a colorfully painted school bus, the destination of which was always Furthur, as indicated on its sign, but also exemplified by the general ethos of the Pranksters themselves.[3] Kesey and the Pranksters became famous for their use of LSD and other psychedelic drugs in hopes of achieving intersubjectivity. The book chronicles the Acid Tests (parties in which LSD-laced Kool-Aid was used to obtain a communal trip), the group's encounters with (in)famous figures of the time, including famous authors, Hells Angels, and the Grateful Dead, and it also describes Kesey's exile to Mexico and his arrests.

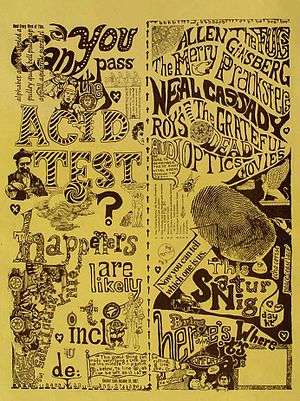

Cover of the first US Edition | |

| Author | Tom Wolfe |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | LSD, beat generation, hippies |

| Publisher | Farrar Straus Giroux |

Publication date | August 1968[1] |

| ISBN | 978-0-553-38064-4 |

| OCLC | 42827164 |

Plot

Tom Wolfe chronicles the adventures of Ken Kesey and his group of followers. Throughout the work, Kesey is portrayed as someone starting a new religion. Due to the allure of the transcendent states achievable through drugs and because of Kesey's ability to preach and captivate listeners, he begins to form a band of close followers. They call themselves the "Merry Pranksters" and begin to participate in the drug-fueled lifestyle. Starting at Kesey's house in the woods of La Honda, California, the early predecessors of acid tests were performed. These tests or mass usage of LSD were performed with lights and noise, which was meant to enhance the psychedelic experience.

The Pranksters eventually leave the confines of Kesey's estate. Kesey buys a bus in which they plan to cross the country. It is driven by the legendary Neal Cassady, the person upon whom Dean Moriarty's character in Jack Kerouac's On the Road was based. They paint it colorfully and name it Furthur. They traverse the nation, tripping on acid throughout the journey. As the Pranksters grow in popularity, Kesey's reputation grows as well. By the middle of the book, Kesey is idolized as the hero of a growing counterculture. He starts friendships with groups like Hells Angels and their voyages lead them to cross paths with icons of the Beat Generation. Kesey's popularity grows to the point that permits the Pranksters to entertain other significant members of a then growing counterculture. The Pranksters meet the Grateful Dead, Allen Ginsberg and attempt to meet with Timothy Leary. The failed meeting with Leary leads to great disappointment. A meeting between Leary and Kesey would mark the meeting of East and West. Leary was on the East Coast, and Kesey represented the West Coast.

In an effort to broadcast their lifestyle, the Pranksters publicise their acid experiences and the term Acid Test comes to life. The Acid Tests are parties where everyone takes LSD (which was often put into the Kool-Aid they served) and abandon the realities of the mundane world in search of a state of "intersubjectivity." Just as the Acid Tests are catching on, Kesey is arrested for possession of marijuana. In an effort to avoid jail, he flees to Mexico and is joined by the Pranksters. The Pranksters struggle in Mexico and are unable to obtain the same results from their acid trips.

Kesey and some of the Pranksters return to the United States. At this point, Kesey becomes a full blown pop culture icon as he appears on TV and radio shows, even as he is wanted by the FBI. Eventually, he is located and arrested. Kesey is conditionally released as he convinces the judge that the next step of his movement is an "Acid Test Graduation", an event in which the Pranksters and other followers will attempt to achieve intersubjectivity without the use of mind-altering drugs. The graduation was not effective enough to clear the charges from Kesey's name. He is given two sentences for two separate offenses. He is designated to a work camp to fulfill his sentence. He moves his wife and children to Oregon and begins serving his time in the forests of California.

Cultural significance and reception

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test is remembered as an accurate and "essential" book depicting the roots and growth of the hippie movement.[4]

The use of New Journalism yielded two primary responses, amazement or disagreement. While The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test was not the original standard for New Journalism, it is the work most often cited as an example for the revolutionary style. Wolfe's descriptions and accounts of Kesey's travel managed to captivate readers and permitted them to read the book as a fiction piece rather than a news story. Those who saw the book as a literary work worthy of praise were amazed by the way Wolfe maintains control.[5] Despite being fully engulfed in the movement and aligned with the Prankster's philosophy, Wolfe manages to distinguish between the realities of the Pranksters and Kesey's experiences and the experiences triggered by their paranoia and acid trips.[5] Wolfe is in some key ways different from the Pranksters, because despite his appreciation for the spiritual experiences offered by the psychedelic, he also accepts the importance of the physical world. The Pranksters see their trips as a breach of their physical worlds and realities. Throughout the book Wolfe focuses on placing the Pranksters and Kesey within the context of their environment. Where the Pranksters see ideas, Wolfe sees Real-World objects.[6]

While some saw New Journalism as the future of literature, the concept was not without critics and criticism. There were many who challenged the believability of the style and there were many questions and criticisms about whether accounts were true.[7] Wolfe however challenged such claims and notes that in books like The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, he was nearly invisible throughout the narrative. He argues that he produced an uninhibited account of the events he witnessed.[8] As proponents of fiction and orthodox nonfiction continued to question the validity of New Journalism, Wolfe stood by the growing discipline. Wolfe realized that this method of writing transformed the subjects of newspapers and articles into people with whom audiences could relate and sympathize.[8]

The New York Times considered the book one of the great works of its time; it described it as not only a great book about hippies, but the "essential book".[4] The review continued to explore the dramatic impacts of Wolfe's telling of Kesey's story. Wolfe's book exposed counterculture norms that would soon spread across the country. The review notes that while Kesey received acclaim for his literary bomb One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, he was, for the most part, not a visible icon. His experiments and drug use were known within small circles, the Pranksters for example. Wolfe's accounts of Kesey and the Pranksters brought their ideologies and drug use to the mainstream.[4] A separate review maintained that Wolfe's book was as vital to the hippie movement as The Armies of the Night was to the anti-Vietnam movement.[9]

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test received praise from some outlets. Others were not as open to its effects. A review in The Harvard Crimson identified the effects of the book, but did so without offering praise.[10][11] The review, written by Jay Cantor, who went on to literary prominence himself, provides a more moderate description of Kesey and his Pranksters. Cantor challenges Wolfe's messiah-like depiction of Kesey, concluding that "In the end the Christ-like robes Wolfe fashioned for Kesey are much too large. We are left with another acid-head and a bunch of kooky kids who did a few krazy things." Cantor explains how Kesey was offered the opportunity by a judge to speak to the masses and curb the use of LSD. Kesey, who Wolfe idolizes for starting the movement, is left powerless in his opportunity to alter the movement. Cantor is also critical of Wolfe's praise for the rampant abuse of LSD. Cantor admits the impact of Kesey in this scenario, stating that the drug was in fact widespread by 1969, when he wrote his criticism.[10][11] He questions the glorification of such drug use however, challenging the ethical attributes of reliance on such a drug, and further asserts that "LSD is no respecter of persons, of individuality".[10][11]

Asked in 1989 by Terry Gross on Fresh Air what he thought of the book, Kesey replied,

It's a good book. yeah, he’s a—Wolfe's a genius. He did a lot of that stuff, he was only around three weeks. He picked up that amount of dialogue and verisimilitude without tape recorder, without taking notes to any extent. He just watches very carefully and remembers. But, you know, he's got his own editorial filter there. And so what he's coming up with is part of me, but it's not all of me. . . ."[12]

References

- Weingarten, Marc (September 3, 2005). "The genesis of gonzo". The Guardian. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- Wolfe, Tom (1968). The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. New York: Bantam. ISBN 0-553-38064-8.

- Reynolds, Stanley (2014-05-02). "Acid adventures - review of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test: From the archive, 2 May 1969". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- Fremont, "Books of the Times."

- Bredahl, "An Exploration of Power: Tom Wolfe's Acid Test.". 83.

- Bredahl, An Exploration of Power: Tom Wolfe's Acid Test. 84.

- Scura, Conversations With Tom Wolfe, 178.

- Scura, Conversations With Tom Wolfe, 132.

- Bryan. "The Pump House Gang and The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test".

- Cantor, "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test".

- "The Electric Kool' Aid Acid Test | News | The Harvard Crimson". www.thecrimson.com. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- Conversations with Ken Kesey, ed. Scott F. Parker (University Press of Mississippi, 2014), 110.

.jpg)