The Agnew Clinic

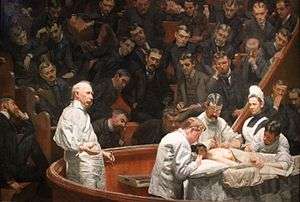

The Agnew Clinic (or The Clinic of Dr. Agnew) is an 1889 oil painting by American artist Thomas Eakins. It was commissioned to honor anatomist and surgeon David Hayes Agnew, on his retirement from teaching at the University of Pennsylvania.

| The Agnew Clinic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Thomas Eakins |

| Year | 1889 |

| Catalog | Goodrich 235 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 214 cm × 300 cm (84 3⁄8 in × 118 1⁄8 in) |

| Location | John Morgan Building, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

Background

The Agnew Clinic depicts Dr. Agnew performing a partial mastectomy in a medical amphitheater. He stands in the left foreground, holding a scalpel. Also present are Dr. J. William White, applying a bandage to the patient; Dr. Joseph Leidy (nephew of paleontologist Joseph Leidy), taking the patient's pulse; and Dr. Ellwood R. Kirby, administering anesthetic. In the background, the operating room nurse, Mary Clymer, and University of Pennsylvania medical school students observe. Eakins placed himself in the painting – he is the rightmost of the pair behind the nurse – although the actual painting of him is attributed to his wife, Susan Macdowell Eakins.[1] The painting, also, records the significant transition, in just 14 years, from the earlier status quo – the participants' black frock coats represented in The Gross Clinic (1875) – to the "white coats" of 1889.[2]

The painting is Eakins's largest work.[3] It was commissioned for $750 (equivalent to $21,342 today) in 1889 by three undergraduate classes at the University of Pennsylvania, to honor Dr. Agnew on the occasion of his retirement.[3] The painting was completed quickly, in three months, rather than the year that Eakins took for The Gross Clinic. Eakins carved a Latin inscription into the painting's frame. Translated, it says: "D. Hayes Agnew M.D. Most experienced surgeon, clearest writer and teacher, most venerated and beloved man."[4][5]

Style

The work is a prime example of Eakins's scientific realism. The rendering is almost photographically precise – so much so that art historians have been able to identify everyone depicted in the painting, with the exception of the patient.[1] It largely repeats the subject of Eakins's earlier The Gross Clinic (1875), seen at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The painting echoes the subject and treatment of Rembrandt's famous Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632) (in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, the Netherlands), and other earlier depictions of public surgery such as the frontispiece of Andreas Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica (1543), the Quack Physicians' Hall (c. 1730) by the Dutch artist Egbert van Heemskerck, and the fourth scene in William Hogarth's The Four Stages of Cruelty (1751).

Mary V. Clymer

Students of the medical class of 1889 who commissioned The Agnew Clinic are portrayed as the audience for the surgery—as historian Amanda Mahoney[6] points out, all individuals depicted in the work can be identified by name, except for the patient—and this audience of male medical students creates a composition that highlights power dynamics between the masculine and the feminine in the academic medical hierarchy.[6] Central to the medical care of the patient yet separate in her femininity stands the woman in white—the nurse, Mary Clymer, who serves as the surgeon Agnew's "structural counterpart" in the composition of the painting, the only other figure on the same level as the surgeon.[7]

Credited by the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) as the first trained operating room nurse in Philadelphia, Mary V. Clymer was born in Mercer County, New Jersey, in 1861 to a prominent Civil War veteran.[6] At the age of 28, Clymer enrolled in the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Training School for Nurses.[8] Graduating in 1889 at the top of her class,[7] Clymer was among the first graduates of HUP's nurse training school, which was established in 1886.[9] Clymer was the recipient of the Nightingale Award for her exceptional patient care and scholarship.[8] Fittingly, Clymer missed her graduation ceremony from the Training School because she was providing emergency care to victims of the 1889 Williamsport flood[6]

Some art historians read Clymer's presence in the painting as sympathetic to the female patient: Clymer looks down at the objectified female figure and feels connection with another body separate from the male-dominated hospital hierarchy.[10] Others argue that Clymer's presence challenges this dynamic: Clymer's presence demonstrates the increasing technical advancements within nursing and medicine, her placement in the scene is a nod to the contributions to sanitation and organization that nurses brought to the operating room.[10][6] Clymer may not look down at the female figure in sympathy but with the cool attention of a trained operating room nurse, one who closely monitors her patient's status and anticipates the needs of the surgical team.[6]

Founded in 1878 and opened in 1886, the HUP Training School for Nursing engaged nursing students in rigorous hands-on and lecture-based learning.[11] During the first month of nursing training, "probationers" began their nursing education providing dietary and cleaning services at the hospital.[11] As they progressed through their nursing education, trainee nurses learned nursing skills on the floor of the hospital and participated in lectures given by physicians at the university hospital.[11] At HUP, Clymer received training through clinical experience providing patient care and lectures presented by the hospital's physicians.[6]

The Clymer Diaries

During her training between 1887 and 1889, Mary Clymer kept diaries that included clinical and lecture notes that have been preserved through the Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing archives. Clymer's diaries reveal daily nursing tasks, practical knowledge learned, and the occasional student's gripe--"Learned nothing new, and everything seemed to go wrong. M.V.C."[12]

Clymer's notes reveal Eakins’ artistic license in the depiction of the mastectomy in The Agnew Clinic—Clymer wrote that, when preparing a patient for operation, one must cover the healthy breast and reveal the affected breast;[13] this is confirmed in Agnew's own writings.[10] Eakins’ choice to leave the patient nude may have been for shock value, to clarify the nature of the depicted procedure, or to simply fulfill the artist's desire to portray a nude female figure.[6]

Not only do the diaries of Mary V. Clymer reveal information regarding operating room etiquette that has been used to help understand The Agnew Clinic, they also detail common practices and materia medica of 19th century medicine employed at HUP during her time there. These medicines and practices include but are not limited to:

- General Medicine

- Beef tea[14]

- Cod liver oil[15]

- Cold baths for fever[16]

- Esmarch bandage[17]

- Turpentine as a hemostatic[18], in the treatment of burns[19], to relieve shortness of breath[20] and in a poultice for swollen bowels.[21]

- Lead acetate, Laudanum, Monsell's solution, and aromatic sulphuric acid as hemostatics.[22]

- Milk products: Peptonized milk, Hot milk, Skim milk, and Buttermilk "only if fresh."[23]

- Opium suppositories[24]

- Soda water to assist in digestion[25]

- Stimulating enema made with turpentine and yolk of egg [26]

- Quinine noted to cause rash, blindness or deafness in some patients[27]

- Care of the Skin

- Casting soap aka glycerin soap used to wash skin and carbonate of sodium and borax to clean skin when rubbing is contraindicated.[28]

- Bran or gelatin powder to protect the skin[29]

- Oxide of zinc for burns, scalds, and blisters[30]

- Zinc powder applied to patients back [31]

- Camphorated oil to prevent bedsores and Croton oil rubbed into the skin is noted as being "stimulating."[32]

- Permanganate of potash for burns[33]

- Wound dressing made with "lead water and laudanum" for dressing of knee amputation [34]

- Disinfectants

- "Alcohol, Borax, Salt, Lime (Chloride, Carbolic acid & Corrosive Stimulate are both)."[35]

- Bichloride of Mercury which "will produce irritation" and Iodoform which "smells badly & is not as active as the others but when wet is very good." [36]

- Carbolic acid as a disinfectant useful only "when it comes in contact with what you want to destroy."[37]

- Chloride of lime as the "best disinfectant."[38]

- Prussic acid "the most violent poison" and Creosote [39]

- Respiratory Support

- Steam inhalation via atomizer or direct inhalation of steaming water for respiratory support[40]

- To alleviate a cough: Flax seed and Irish moss with lemon juice for taste, hot water steam inhalation, Turlington's balsam, Gum Arabic water, Mustard plasteis applied to the chest[41]

- For shortness of breath: Hot brandy or ammonia and hot water; Hoffman's anodyne for adults not children; Turpentine, hortshorn or chloroform liniment[42]

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- "A few [tablets from druggists] we ought always have"[45]:

- 1/4 gr. Morphia

- 1/100 of Atropia

- 1/8 of pilocarpine Ergotine

- 1% Nitroglycerine

Controversy

The Agnew Clinic is one of Eakins's most hotly debated works.[46] His decision to portray a partially nude woman observed by a roomful of men (even though they were doctors, and in an undeniably medical setting) was controversial. It was rejected for exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1891, and at New York's Society of American Artists in 1892. Its exhibition at Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition was criticized.[46]

Related works

Eakins made preparatory sketches for The Agnew Clinic – a drawing of Dr. David Hayes Agnew, an oil study of Agnew, and a compositional sketch for the entire work. Individual studies of all 33 figures were probably made, but none are known to survive.

Eakins later painted a black and white version, specifically to be photographed and reproduced as a photogravure.[47] His friend and protégé, Samuel Murray, modeled a statuette of Eakins at work on the painting.[48]

As of 2009, The Agnew Clinic was on loan from the University of Pennsylvania to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[1]

G-235A. Drawing of Dr. Agnew, Philadelphia Museum of Art

G-235A. Drawing of Dr. Agnew, Philadelphia Museum of Art G-237. Oil study of Dr. Agnew, Yale University Art Gallery

G-237. Oil study of Dr. Agnew, Yale University Art Gallery G-236. Compositional sketch, private collection.

G-236. Compositional sketch, private collection.- Statuette: Thomas Eakins at work on The Agnew Clinic (1889) by Samuel Murray.

Notes

- Medical Class of 1889 and Thomas Eakins' painting of "The Agnew Clinic". University of Pennsylvania Archives and Records Center.

- Hardy, Susan and Corones, Anthony, "Dressed to Heal: The Changing Semiotics of Surgical Dress", Fashion Theory, (2015), pp.1–23. doi=10.1080/1362704X.2015.1077653

- Stefan C. Schatzki. "The Agnew Clinic." The American Journal of Roentgenology. Volume 160, Issue 5, 1993.

- Kirkpatrick, 396.

- Agnew Clinic with frame from Flickr.

- pennalumni (November 12, 2009), "The Agnew Clinic: Through the Eyes of a Nurse" (Penn Homecoming 2009), retrieved November 20, 2017

- Fryer, Judith (1991). The Female Body: Figures, Styles, Speculations. University of Michigan Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0472064779.

- "Bates Center Finding Aid Mary V. Clymer papers". Barbara Bates Center for The Study of The History of Nursing. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- "History". www.nursing.upenn.edu. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- Athens, Elizabeth (July 2006). "Knowledge and Authority and Thormas Eakin's 'The Agnew Clinic'". The Burlington Magazine. 148 (1240): 482–485. JSTOR 20074493.

- "A Cornerstone of Nursing Education: HUP's School of Nursing – PR News". www.pennmedicine.org. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 1". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 75v V1. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary (October 2017). "Lecture Notes c. 1887–1889". Archives of the Barbara Bates Center for the History of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 3r V.2. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 4v V.2. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 6r V2. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 1". p. 60r V.1. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 16v V.2. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 34r V.2. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 56r V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 99v V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 16v V.2; 17v V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 20v V.2; 20r V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 34v V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 20v V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 1". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 59r V.1. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 67r V.2. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 15r V.2. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 15r V.2. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 15v V.2. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 1". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 74r V.1. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 15v V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 35r V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 1". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 73r V.1. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 65r V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 31r V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 12v V.2. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 12v V.2.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 67v V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 10r V.2. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 55v V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 56r V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 18v V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 58v V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clymer, Mary. "The Clymer Diaries Volume 2". The Barbara Bates Center for The Study of the History of Nursing. p. 43v V.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Kirkpatrick, 390.

- Philadelphia Museum of Art Website

- Thomas Eakins by Samuel Murray from Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sources

- Sidney Kirkpatrick. The Revenge of Thomas Eakins. Yale University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-300-10855-2.