Thanksgiving (Canada)

Thanksgiving (French: Action de grâce), or Thanksgiving Day (French: Jour de l'Action de grâce), sometimes called Canadian Thanksgiving to distinguish it from the American holiday of the same name, is an annual Canadian holiday, occurring on the second Monday in October, which celebrates the harvest and other blessings of the past year.[1]

| Thanksgiving | |

|---|---|

Shopping for pumpkins for Thanksgiving in Ottawa's ByWard Market in 1991. | |

| Observed by | Canada |

| Type | Cultural |

| Significance | A celebration of being thankful for what one has and the bounty of the previous year. |

| Celebrations | Spending time with family, feasting, religious practice |

| Date | Second Monday in October |

| 2019 date | October 14 |

| 2020 date | October 12 |

| 2021 date | October 11 |

| 2022 date | October 10 |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Thanksgiving in the United States |

Thanksgiving has been officially celebrated as an annual holiday in Canada since November 6, 1879.[2] While the date varied by year and was not fixed, it was commonly the third Monday in October.[2]

On January 31, 1957, the Governor General of Canada Vincent Massey issued a proclamation stating: "A Day of General Thanksgiving to Almighty God for the bountiful harvest with which Canada has been blessed – to be observed on the second Monday in October."[3]

Statutory holiday

Thanksgiving is a statutory holiday in most of Canada, with the exceptions being the Atlantic provinces of Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, where it is an optional holiday.[4][5] Companies that are regulated by the federal government (such as those in the telecommunications and banking sectors) recognize the holiday regardless of its provincial status.[6][7][8][9][10]

Traditional celebration

As a liturgical festival, Thanksgiving corresponds to the British and continental European harvest festival, with churches decorated with cornucopias, pumpkins, corn, wheat sheaves, and other harvest bounty. British and European harvest hymns are sung on the Sunday of Thanksgiving weekend.

While the actual Thanksgiving holiday is on a Monday, Canadians may gather for their Thanksgiving feast on any day during the long weekend; however, Sunday is considered the most common. Foods traditionally served at Thanksgiving include roasted turkey, stuffing, mashed potatoes with gravy, sweet potatoes, cranberry sauce, sweet corn, various autumn vegetables (mainly various kinds of squashes but also Brussels sprouts), and pumpkin pie. Baked ham and apple pie are also fairly common, and various regional dishes and desserts may also be served, including salmon, wild game, Jiggs dinner with split-pea pudding, butter tarts, and Nanaimo bars.[11]

In Canadian football, the Canadian Football League has usually held a nationally televised doubleheader, the Thanksgiving Day Classic. It is one of two weeks in which the league plays on Monday afternoons,[12] the other being the Labour Day Classic.

Kitchener-Waterloo Oktoberfest holds a Thanksgiving parade on the holiday; it is broadcast on CTV on tape-delay. The parade consists of floats, civic figures in the region, local performance troupes and marching bands.[13]

Canadian Thanksgiving coincides with the observance in the United States of Columbus Day and the American Indigenous Peoples' Day. As such, American towns with high levels of Canadian tourism will often hold their fall festivals over Thanksgiving/Columbus Day weekend, in part to draw and accommodate Canadian tourists; the Fall Festival of Ellicottville, New York, has been identified as an "annual pilgrimage" for Canadians.[14] Border towns also often experience an uptick in shoppers at grocery stores, as Canadian shoppers take advantage of lower sales taxes and commodity prices in the United States over the long holiday.[15]

History

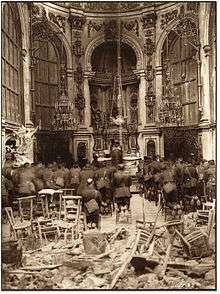

According to some historians, the first celebration of Thanksgiving in North America occurred during the 1578 voyage of Martin Frobisher from England, in search of the Northwest Passage.[2] His third voyage, to the Frobisher Bay area of Baffin Island in the present Canadian Territory of Nunavut, set out with the intention of starting a small settlement. His fleet of fifteen ships was outfitted with men, materials, and provisions. However, the loss of one of his ships through contact with ice, along with many of the building materials, was to prevent him from doing so. The expedition was plagued by ice and freak storms, which at times scattered the fleet; on meeting again at their anchorage in Frobisher Bay, "... Mayster Wolfall, a learned man, appointed by Her Majesty's Counsel to be their minister and preacher, made unto them a godly sermon, exhorting them especially to be thankful to God for their strange and miraculous deliverance in those so dangerous places ...". They celebrated Holy Communion and "The celebration of divine mystery was the first sign, scale, and confirmation of Christ's name, death and passion ever known in all these quarters."[16] (The notion of Frobisher's service being first on the continent has come into dispute, as Spaniards conducted similar services in Spanish North America during the mid-16th century, decades before Frobisher's arrival.[17][18])

Years later, French settlers, having crossed the ocean and arrived in Canada with explorer Samuel de Champlain, from 1604, also held feasts of thanks. They formed the Order of Good Cheer and held feasts with their First Nations neighbours, at which food was shared.

After the Seven Years' War ended in 1763, with New France handed over to the British, the citizens of Halifax held a special day of Thanksgiving. Thanksgiving days were observed beginning in 1799 but did not occur every year.[19]

During and after the American Revolution, American refugees who remained loyal to Great Britain moved from the newly independent United States to Canada. They brought the customs and practices of the American Thanksgiving to Canada, such as the turkey, pumpkin, and squash.[20]

Lower Canada and Upper Canada observed Thanksgiving on different dates; for example, in 1816 both celebrated Thanksgiving for the termination of the War of 1812 between France, the U.S. and Great Britain, with Lower Canada marking the day on May 21 and Upper Canada on June 18 (Waterloo Day).[19] In 1838, Lower Canada used Thanksgiving to celebrate the end of the Lower Canada Rebellion.[19] Following the rebellions, the two Canadas were merged into a united Province of Canada, which observed Thanksgiving six times from 1850 to 1865.[19] During this period, Thanksgiving was a solemn, mid-week celebration.[21]

The first Thanksgiving Day after Confederation was observed as a civic holiday on April 5, 1872, to celebrate the recovery of the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) from a serious illness.[22]

For many years before it was declared a national holiday in 1879, Thanksgiving was celebrated in either late October or early November. From 1879 onward, Thanksgiving Day has been observed every year, the date initially being a Thursday in November.[23] After World War I, an amendment to the Armistice Day Act established that Armistice Day and Thanksgiving would, starting in 1921, both be celebrated on the Monday of the week in which November 11 occurred.[22] Ten years later, in 1931, the two days became separate holidays, and Armistice Day was renamed Remembrance Day. From 1931 to 1957, the date was set by proclamation, generally falling on the second Monday in October, except for 1935, when it was moved due to a general election.[19][22] In 1957, Parliament fixed Thanksgiving as the second Monday in October.[22] The theme of the Thanksgiving holiday also changed each year to reflect an important event to be thankful for. In its early years it was for an abundant harvest and occasionally for a special anniversary.[19]

See also

- Thanksgiving

- Public holidays in Canada

References

- Sismondo, Christine (October 5, 2017). "The odd, complicated history of Canadian Thanksgiving". Macleans.ca. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- Thanksgiving Day, Canadian Encyclopedia

- Kelch, Kalie (August 27, 2013). Grab Your Boarding Pass. Review & Herald Publishing Association. p. 12. ISBN 9780812756548.

- "Statutory Holidays in Canada". Retrieved October 6, 2012.

- Not excepting Atlantic Province of Nova Scotia: Retail Business Designated Day Closing Act (Nova Scotia)

- "Paid public holidays". WorkRights.ca. Archived from the original on December 18, 2010.

- "Thanksgiving – is it a Statutory Holiday?". Government of Nova Scotia. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- "Statutes, Chapter E-6.2" (PDF). Government of Prince Edward Island. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- "RSNL1990 Chapter L-2 – Labour Standards Act". Assembly of Newfoundland. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- "Statutory Holidays" (PDF). Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development, Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 29, 2008.

- Scottie Andrew. "6 ways Canadian Thanksgiving is different from the US holiday". CNN.

- 2018 CFL Game Notes: 73. Calgary at Montreal, October 2018, retrieved March 4, 2019.

- "Parade – Welcome to Kitchener-Waterloo Oktoberfest Thanksgiving Day Parade". Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- Smiles at Ellicottville Fall Festival: See who made the annual pilgrimage to Ellicottville. The Buffalo News (October 10, 2016). Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- Raguse, Lou (October 14, 2013). Canadian Thanksgiving brings shoppers Archived December 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. WIVB-TV. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- Collinson, Richard (April 22, 2010). The three voyages of Martin Frobisher: in search of a passage to Cathai and India by the northwest AD 1576–1578. ISBN 978-1108010757.

- Wilson, Craig (November 21, 2007). "Florida teacher chips away at Plymouth Rock Thanksgiving myth". Usatoday.com. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- Davis, Kenneth C. (November 25, 2008). "A French Connection". Nytimes.com. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- "Proclamation and Observance of General Thanksgiving Days and reasons therefore". Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2010.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Solski, Ruth. Canada's Traditions and Celebrations. On the Mark Press. p. 12. ISBN 1550356941.

- Stevens, Peter (October 9, 2017). "The religious and nationalist origins of Canadian Thanksgiving". Toronto Star. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- "Thanksgiving and Remembrance Day". Canadian Heritage. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- "Canadian Thanksgiving Day History". Kidzworld.com. Retrieved November 17, 2012.