Tel Megiddo

Tel Megiddo (Hebrew: מגידו; Arabic: مجیدو, Tell al-Mutesellim, lit. "Tell of the Governor"; Greek: Μεγιδδώ, Megiddo) is the site of the ancient city of Megiddo whose remains form a tell (archaeological mound), situated in northern Israel near Kibbutz Megiddo, about 30 km south-east of Haifa. Megiddo is known for its historical, geographical, and theological importance, especially under its Greek name Armageddon. During the Bronze Age, Megiddo was an important Canaanite city-state and during the Iron Age, a royal city in the Kingdom of Israel. Megiddo drew much of its importance from its strategic location at the northern end of the Wadi Ara defile, which acts as a pass through the Carmel Ridge, and from its position overlooking the rich Jezreel Valley from the west. Excavations have unearthed 26 layers of ruins since the Chalcolithic phase, indicating a long period of settlement.[1] The site is now protected as Megiddo National Park and is a World Heritage Site.[2]

מגידו | |

Aerial view of Tel Megiddo | |

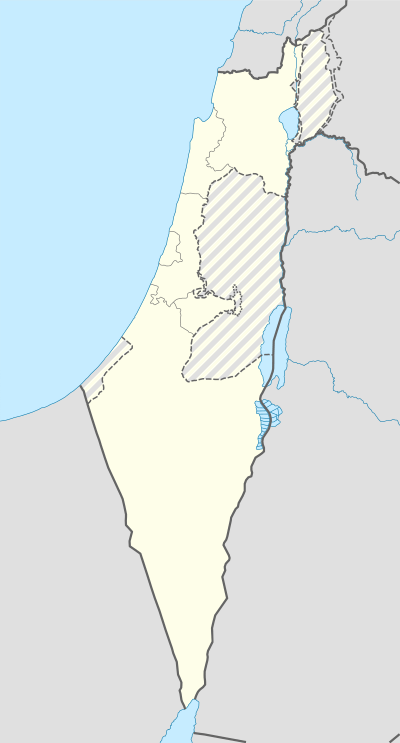

Shown within Israel | |

| Location | Near Kibbutz Megiddo, Israel |

|---|---|

| Region | Levant |

| Coordinates | 32°35′07″N 35°11′04″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Abandoned | 586 BCE |

| Official name | Biblical Tells – Megiddo, Hazor, Beer Sheba |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 2005 (29th session) |

| Reference no. | 1108 |

| State Party | Israel |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

Etymology

Megiddo was known in the Akkadian language used in Assyria as Magiddu, Magaddu; in Egyptian as Maketi, Makitu, and Makedo; in the Canaanite-influenced Akkadian used in the Amarna tablets, as Magidda and Makida; Greek: Μεγιδδώ/Μαγεδδών,[3] Megiddó/Mageddón in the Septuagint; Latin: Mageddo in the Vulgate.[4]

The Book of Revelation mentions an apocalyptic battle at Armageddon (Revelation 16:16): Ἁρ¦μαγεδών (Har¦magedōn),[5] a Koine Greek name of the site, derived from the Hebrew "Har Megiddo", meaning "Mount of Megiddo".[6] "Armageddon" has become a byword for the end of the world.[7]

History

Megiddo was important in the ancient world. It guarded the western branch of a narrow pass on the most important trade route of the ancient Fertile Crescent, linking Egypt with Mesopotamia and Asia Minor and known today as Via Maris. Because of its strategic location, Megiddo was the site of several battles. It was inhabited approximately from 6500 to 600 BCE,[8] or even since around 7000 BCE,[9] though the first significant remains date to the Chalcolithic period (4500–3500 BCE).

Early Bronze Age

Megiddo's Early Bronze Age I (3500–3100 BCE) temple was described by its excavators as "the most monumental single edifice so far uncovered" in the [early Bronze Age] Levant and among the largest structures of its time in the Near East.[10] Samples, obtained at the temple-hall in year 2000, provided calibrated dates from the 31st and 30th century BCE,[11] the temple is the most monumental Early Bronze I structure known in the Levant, if not the entire Ancient Near East. Archaeologists' view is that "taking into account the manpower and administrative work required for its construction, it provides the best manifestation for the first wave of urban life and, probably, city-state formation in the Levant".[12] To the South of this temple there is an unparalleled monumental compound which was excavated by the Megiddo Expedition in 1996 and 1998, and belongs to the later phase of Early Bronze IB (3300-3100 BCE). It consists of several long, parallel stone walls, each of which is 4 meters wide. Between the walls were narrow corridors, filled hip-deep with the remains of animal sacrifice. These walls lie immediately below the huge ‘megaron’ temples of the Early Bronze III (2700-2300 BCE).[13]

Magnetometer research has found the entire Tel Megiddo settlement covered an area of ca. 50 hectares, being the largest Early Bronze Age I site known in the Levant.[14]

The town declined in the Early Bronze Age IV period (2300–2000 BCE) as the Early Bronze Age political systems collapsed at the last quarter of the third millennium BCE.[15]

Middle Bronze Age

Early in the second millennium BCE, at the beginning of Middle Bronze Age, urbanism once again took hold throughout of the southern Levant and large urban centers served as political power in city-states, by the later Middle Bronze Age the inland valleys were dominated by regional centers such as Megiddo which reached a size of more than 20 hectares (including the upper and lower cities).[16] A royal burial was found in Tel Megiddo, dating to the later phase of the Middle Bronze Age, around 1700-1600 BCE, when the power of Canaanite Megiddo was at its peak and before the ruling dynasty collapsed under the might of Thutmose's army.[17]

Late Bronze Age

At the Battle of Megiddo the city was subjugated by Thutmose III (r. 1479–1425 BCE), and became part of the Egyptian Empire. However, the city still prospered, and a massive and elaborate government palace was constructed in the Late Bronze Age.[18]

In the Amarna Period (c. 1350 BC), Megiddo was a vassalage of the Egyptian Empire. The Amarna Letter E245 mentions local ruler Biridiya of Megiddo. Other contemporary rulers mentioned were Labaya of Shechem and Surata of Akka, nearby cities. This ruler is also mentioned in the corpus from the city of 'Kumidu', the Kamid al lawz. This indicates that there was relations between Megiddo and Kumidu.

Iron Age

The city was destroyed around 1150 BCE, and the area was resettled by what some scholars believe to be early Israelites. The city represented by Stratum VI seems to have been a mixed Israelite and Philistine character, and fell victim to fire.[19] When the Israelites captured it, though, it became an important city, before being destroyed, possibly by Aramaean raiders, and rebuilt, this time as an administrative center for Tiglath-Pileser III's occupation of Samaria. In 609 BC, Megiddo was conquered by Egyptians under Necho II during the Battle of Megiddo. However, its importance soon dwindled, and it was finally abandoned around 586 BCE.[20] Since that time it has remained uninhabited, preserving ruins pre-dating 586 BCE without settlements ever disturbing them. Instead, the town of al-Lajjun (not to be confused with the al-Lajjun archaeological site in Jordan) was built up near to the site, but without inhabiting or disturbing its remains.

Modern Israel

Kibbutz Megiddo is nearby, less than 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) to the south. Today, Megiddo Junction is on the main road connecting the center of Israel with lower Galilee and the north. It lies at the northern entrance to Wadi Ara, an important mountain pass connecting the Jezreel Valley with Israel's coastal plain.[21]

In 1964, during Pope Paul VI's visit to the Holy Land, Megiddo was the site where he met with Israeli dignitaries, including Israeli President Zalman Shazar and Prime Minister Levi Eshkol.[22]

Battles

Famous battles include:

- Battle of Megiddo (15th century BCE): fought between the armies of the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III and a large Canaanite coalition led by the rulers of Megiddo and Kadesh.

- Battle of Megiddo (609 BCE): fought between Egyptian pharaoh Necho II and the Kingdom of Judah, in which King Josiah fell.

- Battle of Megiddo (1918): fought during World War I between Allied troops, led by General Edmund Allenby, and the defending Ottoman army.

History of archaeological excavation

Megiddo has been excavated three times and is currently being excavated yet again. The first excavations were carried out between 1903 and 1905 by Gottlieb Schumacher for the German Society for the Study of Palestine.[23] Techniques used were rudimentary by later standards and Schumacher's field notes and records were destroyed in World War I before being published. After the war, Carl Watzinger published the remaining available data from the dig.[24]

In 1925, digging was resumed by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, financed by John D. Rockefeller, Jr., continuing until the outbreak of the Second World War. The work was led initially by Clarence S. Fisher, and later by P. L. O. Guy, Robert Lamon, and Gordon Loud.[25][26][27] [28] [29] [30] The Oriental Institute intended to completely excavate the whole tel, layer by layer, but money ran out before they could do so. Today excavators limit themselves to a square or a trench on the basis that they must leave something for future archaeologists with better techniques and methods. During these excavations it was discovered that there were around 8 levels of habitation, and many of the uncovered remains are preserved at the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem and the Oriental Institute of Chicago. The East Slope area of Megiddo was excavated to the bedrock to serve as a spoil area. The full results of that excavation were not published until decades later. [31]

Yigael Yadin conducted excavations in 1960, 1966, 1967, and 1971 for the Hebrew University.[32][33] The formal results of those digs were published by Anabel Zarzecki-Peleg in Hebrew University's monograph 2016 Qedem 56. [34]

Megiddo has most recently (since 1994) been the subject of biannual excavation campaigns conducted by the Megiddo Expedition of Tel Aviv University, currently co-directed by Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, with Eric H. Cline of The George Washington University serving as Associate Director (USA), together with a consortium of international universities.[35][36] One notable feature of the dig is close on-site co-operation between archaeologists and specialist scientists, with detailed chemical analysis being performed at the dig itself using a field infrared spectrometer.[37]

In 2010, the Jezreel Valley Regional Project, directed by Matthew J. Adams of Bucknell University in cooperation with the Megiddo Expedition, undertook excavations of the eastern extension of the Early Bronze Age town of Megiddo, at the site known as Tel Megiddo (East).[38]

Archaeological features

A path leads up through a Solomonic gateway overlooking the excavations of the Oriental Institute. A solid circular stone structure has been interpreted as an altar or a high place from the Canaanite period. Further on is a grain pit from the Israelite period for storing provisions in case of siege; the stables, originally thought to date from the time of Solomon but now dated a century and a half later to the time of Ahab; and a water system consisting of a square shaft 35 metres (115 ft) deep, the bottom of which opens into a tunnel bored through rock for 100 metres (330 ft) to a pool of water.

The Great Temple

Megiddo's 5,000 year old "Great Temple", dated to the Early Bronze Age I (3500–3100 BCE), has been described by its excavators as "the most monumental single edifice so far uncovered in the EB I Levant and ranks among the largest structures of its time in the Near East."[39] The structure includes an immense, 47.5 by 22 meters sanctuary. The temple is more than ten times larger than the typical temple of that era. The first wall was constructed in the Early Bronze Age II or III period. It was determined that the temple was the site of ritual animal sacrifice. Corridors were used as favissae (deposits of cultic artifacts) to store bones after ritual sacrifice. More than 80% of the animal remains were of young sheep and goats; the rest were cattle.[40]

Jewelry

In 2010, a collection of jewelry pieces was found in a ceramic jug [41][42] The jewelry dates to around 1100 BCE[43] The collection includes beads made of carnelian stone, a ring and earrings. The jug was subjected to molecular analysis to determine the contents. The collection was probably owned by a wealthy Canaanite family, likely belonging to the ruling elite.[44]

Megiddo ivories

The Megiddo ivories are thin carvings in ivory found at Tel Megiddo, the majority excavated by Gordon Loud. The ivories are on display at the Oriental Institute of Chicago and the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem. They were found in the stratum VIIA, or Late Bronze Age layer of the site. Carved from hippopotamus incisors from the Nile, they show Egyptian stylistic influence. An ivory pen case was found inscribed with the cartouche of Ramses III.

Megiddo stables

At Megiddo two stable complexes were excavated from Stratum IVA, one in the north and one in the south. The southern complex contained five structures built around a lime paved courtyard. The buildings themselves were divided into three sections. Two long stone paved aisles were built adjacent to a main corridor paved with lime. The buildings were about twenty-one meters long by eleven meters wide. Separating the main corridor from outside aisles was a series of stone pillars. Holes were bored into many of these pillars so that horses could be tied to them. Also, the remains of stone mangers were found in the buildings. These mangers were placed between the pillars to feed the horses. It is suggested that each side could hold fifteen horses, giving each building an overall capacity of thirty horses. The buildings on the northern side of the city were similar in their construction. However, there was no central courtyard. The capacity of the northern buildings was about three hundred horses altogether. Both complexes could hold from 450–480 horses combined.

The buildings were found during excavations between 1927 and 1934. The head excavator originally interpreted the buildings as stables. Since then his conclusions have been challenged by James Pritchard, Dr Adrian Curtis of Manchester University Ze'ev Herzog, and Yohanan Aharoni, who suggest they were storehouses, marketplaces or barracks.[45]

Megiddo church

The Megiddo church is not on the tell of Megiddo, but nearby next to Megiddo Junction inside the precinct of the Megiddo Prison. It was built within the ancient city of Legio and is believed to date to the 3rd century, which would make it one of the oldest churches in the world.

See also

- al-Lajjun

- Cities of the ancient Near East

References

- Tourist Israel: "...Excavation has uncovered about 26 layers of settlements dating back to the Chalcolithic period..."

- "UNESCO World Heritage Centre - Document - Tel Megiddo National Park".

- World Heritage Sites in Israel, p. 29.

- English Latin Bible: Biblia Sacra Vulgata 405, Second Kings 23:29: "...et abiit Iosias rex in occursum eius et occisus est in Mageddo cum vidisset eum..."

- Biblehub: Revelation 16:16, in original Koine Greek.

- Introducing Megiddo, in Megiddo Expedition, retrieved on 25 March 2020: "...In the New Testament it appears as Armageddon (a Greek corruption of the Hebrew Har [=Mount] Megiddo), location of the millennial battle between the forces of good and evil..."

- Tourist Israel: "...For Christians the word Megiddo is synonymous with the end of the world as mentioned in the Book of Revelation, Megiddo or Armageddon as it is also known will be the site of the Final Battle..."

- The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities,Megiddo. in Archaeology & History of the Land of the Bible International MA in Ancient Israel Studies, Tel Aviv University: "...Megiddo has a 6,000-years history of continuous settlement and is repeatedly named in the ancient archives of Egypt and Assyria...a fascinating picture of state-formation and social evolution in the Bronze Age (ca. 3500-1150 B.C.) and Iron Age (ca. 1150-600 B.C.)..."

- Introducing Megiddo, in Megiddo Expedition, retrieved on 21 March 2020.

- Wiener, Noah." Early Bronze Age: Megiddo's Great Temple and the Birth of Urban Culture in the Levant" Bible History Daily, Biblical Archaeology Society, 2014.

- Megiddo Expedition 2004, in Area J of Tel Megiddo.

- Megiddo Expedition 2006, in Area J of Tel Megiddo.

- Megiddo Expedition 1994-1998, in Area J of Tel Megiddo.

- Megiddo Expedition 2006, in Area J of Tel Megiddo.

- Golden, Jonathan M., 2004. Ancient Canaan and Israel: New Perspectives, ABC-CLIO, Library of Congress, Santa Barbara-California, p. 144.

- Golden, Jonathan M., 2004. Ancient Canaan and Israel: New Perspectives, ABC-CLIO, Library of Congress, Santa Barbara-California, pp. 144-145.

- Bohstrom, Phlippe, (13 March 2018). "Exclusive Royal Burial in Ancient Canaan May Shed New Light on Biblical City", in National Geographic.

- "Merchants and Empires. Late Bronze Age. 1539-1200 BCE". University of Penn Museum.

- Wiener, Noah." Early Bronze Age: Megiddo's Great Temple and the Birth of Urban Culture in the Levant" Bible History Daily, Biblical Archaeology Society, 2014.

- Bahn, Paul. Lost Cities: 50 Discoveries in World Archaeology. London: Barnes & Noble, Inc., 1997. 88–91. Print.

- Davies, Graham, Megiddo, (Lutterworth press, 1986), pg 1.

- History of Megiddo Archived 2009-05-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Schumacher, Gottlieb; Watzinger, Carl (1908): Tell el Mutesellim; Bericht über die 1903 bis 1905 mit Unterstützung SR. Majestät des deutschen Kaisers und der Deutschen Orientgesellschaft vom deutschen Verein zur Erforschung Palästinas Veranstalteten Ausgrabungen Volume: 1

- Schumacher, Gottlieb; Watzinger, Carl, 1877-1948, (1929): Tell el Mutesellim; Bericht über die 1903 bis 1905 mit Unterstützung SR. Majestät des deutschen Kaisers und der Deutschen Orientgesellschaft vom deutschen Verein zur Erforschung Palästinas Veranstalteten Ausgrabungen, vol. 2.

- oi.uchigao.edu Clarence S. Fisher, The Excavation of Armageddon, Oriental Institute Communications 4, University of Chicago Press, 1929

- oi.uchigao.edu P. L. O. Guy, New Light from Armageddon: Second Provisional Report (1927-29) on the Excavations at Megiddo in Palestine, Oriental Institute Communications 9, University of Chicago Press, 1931

- oi.uchigao.edu Robert S. Lamon and Geoffrey M. Shipton, Megiddo 1. Seasons of 1925-34: Strata I-V, Oriental Institute Publication 42, Oriental Institute of Chicago, 1939, ISBN 0-226-14233-7

- , Gordon Loud, Megiddo 2. Seasons of 1935-1939 - The Text, Oriental Institute Publication 62, Oriental Institute of Chicago, 1948, ISBN 978-9652660138

- Gordon Loud (1948). Plates (PDF). oi.uchigao.edu. Megiddo 2. Seasons of 1935-1939, Oriental Institute Publication 62, Oriental Institute of Chicago. ISBN 0-226-49385-7.

- oi.uchigao.edu Timothy P. Harrison, Megiddo 3. Final Report on the Stratum VI Excavations, Oriental Institute Publication 127, Oriental Institute of Chicago, 2004, ISBN 1-885923-31-7

- Eliot Braun, Early Megiddo on the East Slope (the “Megiddo Stages”): A Report on the Early Occupation of the East Slope of Megiddo (Results of the Oriental Institute’s Excavations, 1925-1933, Oriental Institute Publication 139, Oriental Institute of Chicago, 2013, ISBN 978-1-885923-98-1

- Yigael Yadin, "New Light on Solomon's Megiddo," Biblical Archaeology, vol. 23, pp. 62–68, 1960

- Yigael Yadin, "Megiddo of the Kings of Israel," Biblical Archaeology, vol. 33, pp. 66–96, 1970

- Anabel Zarzecki-Peleg, Yadin's Expedition to Megiddo - Final Report of the Archaeological Excavations (1960,1966,1967, and 1971/2 Seasons, Vols. I&II, Jerusalem, Israel Exploration Society - Qedem #56, Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2016

- Israel Finkelstein, David Ussishkin and Baruch Halpern (eds.), Megiddo III: The 1992–1996 Seasons, Tel Aviv University, 2000, ISBN 965-266-013-2

- Israel Finkelstein, David Ussishkin and Baruch Halpern (eds.), Megiddo IV: The 1998–2002 Seasons, Tel Aviv University, 2006, ISBN 965-266-022-1

- Haim Watzman (2010), Chemists help archaeologists to probe biblical history, Nature, 468 614–615. doi:10.1038/468614a

- "Early Bronze Age: Megiddo's Great Temple and the Birth of Urban Culture in the Levant - Biblical Archaeology Society". 9 October 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Wiener, Noah. "Early Bronze Age: Megiddo's Great Temple and the Birth of Urban Culture in the Levant" Bible History Daily, Biblical Archaeology Society, 2014.

- 5,000-year Old Megiddo Temple Yields Evidence of Industrial Animal Sacrifice Haaretz, October 1, 2014

- Unique Gold Earring Found in Intriguing Collection of Ancient Jewelry at Tel Megiddo

- "Gold Egyptian Earring Found in Israel". Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Hasson, Nir (2012-05-22). "Megiddo Dig Unearths Cache of Buried Canaanite Treasure". Haaretz. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Trove of 3,000-year-old jewelry found in Israel

- Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 476–78.

Further reading

- Gordon Loud, The Megiddo Ivories, Oriental Institute Publication 52, University of Chicago Press, 1939 ISBN 978-0-226-49390-9

- P. L. O. Guy, Megiddo Tombs, Oriental Institute Publications 33, The University of Chicago Press, 1938

- Robert S. Lamon, The Megiddo Water System, Oriental Institute Publication 32, University of Chicago Press, 1935

- H.G. May, Material Remains of the Megiddo Cult, Oriental Institute Publication 26, University of Chicago Press, 1935

- Geoffrey M. Shipton, Notes on the Megiddo Pottery of Strata VI-XX, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 17, University of Chicago Press, 1939

- Gabrielle V. Novacek, Ancient Israel: Highlights from the Collections of the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, Oriental Institute Museum Publications 31, Oriental Institute, 2011 ISBN 978-1-885923-65-3

- The Megiddo Ivories, John A. Wilson, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 42, No. 3 (Jul. - September, 1938), pp. 333–336

- Luxurious forms: Redefining a Mediterranean "International Style," 1400-1200 B.C., Marian H Feldman, The Art Bulletin, New York, March 2002. Vol. 84, Iss. 1

- Rupert Chapman, Putting Sheshonq I in his Place, 2009 (dating, context and analysis of the Sheshonq Fragment), with a reconstructionof the stele at

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tel Megiddo. |

- Tel Megiddo National Park - official site at the Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority

- The Megiddo Expedition

- Jezreel Valley Regional Project

- Pamela Weintraub, Rewriting Tel Megiddo's Violent History: At the ancient site of Megiddo, archaeologists unearth new scientific insights that may turn centuries of gospel on its head., Discover Magazine, November 2015 issue

- Megiddo At Bibleplaces.com

- Megiddo: Tell el-Mutesellim from Images of Archaeological Sites in Israel

- "Mageddo". Catholic Encyclopedia. - contains list of Biblical references

- Excavation of an early christian building in Megiddo, with floor mosaics (fish) and three inscriptions

- The Devil Is Not So Black as He Is Painted: BAR Interviews Israel Finkelstein Biblical Archaeology Review

- Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago Palestine Collection

- The Megiddo Expedition: Archaeology and the Bible, UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research VIII (2005)

- H.G. May Archaeology of Palestine Collection - contains images of several archaeological sites, including Tel Megiddo

- English translation Schumacher's Tell el-Mutesellim, Volume I: Report of Finds