TVET (Technical and Vocational Education and Training)

TVET (Technical and Vocational Education and Training) is education and training which provides knowledge and skills for employment.[1] TVET uses formal, non-formal and informal learning.[2] TVET is recognised to be a crucial vehicle for social equity, inclusion and sustainable development.[3]

Development of the term TVET

The term 'Technical and Vocational Education and Training or TVET was officiated at the World Congress on TVET in 1999 in Seoul, Republic of Korea. The congress recognised the term TVET to be broad enough to incorporate other terms that had been used to describe similar educational and training activities including Workforce Education (WE), and Technical-Vocational Education (TVE). The term TVET parallels other types of education and training e.g. Vocational Education but is also used as an umbrella term to encompass education and training activities.[4]

The decision in 1999 to officiate the term TVET led to the development of the UNESCO-UNEVOC International Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training in Bonn, Germany.[4]

Aims and Purposes of TVET

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) serves multiple purposes. A key purpose is preparation of youth for work. This takes the form of learning and developing work related skills and mastery of underlying knowledge and scientific principles. Work is broadly defined and therefore refers to both formal employment and self-employment. To support self-employment, TVET curricula often include entrepreneurship training. Related to this is the social reproduction and transformation of occupational and vocational practices.[5][6]

A related role is continuing professional development. The rapid technological changes demand that workers continuously update their knowledge and skills. Unlike the past where a job could be held for life, it is common place to change vocations several times. TVET enables that flexibility in two ways. One is providing broad based technical knowledge and transversal skills on which different occupations can be based on. The second is providing continuing vocational training to workers.[5][6] In contrast with the industrial paradigm of the old economy, today's global economy lays the onus on the worker to continually reinvent himself or herself. In the past, workers were assured of a job for life, with full-time employment, clear occupational roles and well established career paths. This is no longer the case. The knowledge dependent global economy is characterized by rapid changes in technology and related modes of work. Often, workers find themselves declared redundant and out of work. TVET today has the responsibility of re-skilling such workers to enable them find and get back to work Apart from providing work related education, TVET is also a site for personal development and emancipation. These concerns the development of those personal capacities that relate to realizing one's full potential with regard to paid or self employment, occupational interests, and life goals outside of work. At the same time TVET seeks to enable individual overcome disadvantages due to circumstances of birth or prior educational experiences.[5][6][7][8]

From a development point of view, TVET facilitates economic growth by increasing the productivity of workers. The returns from increased output far exceed the costs of training, direct and indirect, leading to economic growth.[9] TVET like any other form of education also facilitates socio-economic development by enhancing the capacity of individuals to adopt practices that are socially worthwhile.[7] As a form of education similar to all others, TVET aims to developing the broad range of personal capabilities that characterize an educated person. Thus, the provision of broad based knowledge seeks to ensure critic-creative thinking. TVET also aims at developing capacities for effective communication and effective interpersonal relations.[5][6]

Hybridisation

Because of TVET's isolation with other education streams it was not widely adopted, in particularly in secondary education. Steps were taken to reduce segmentation of education and training and to address institutional barriers that restricted TVET learners′ options including choices to move vertically to higher levels of learning, or horizontally to other streams.

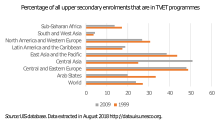

Policy-makers have introduced forms of hybridization with other education systems, additionally some of the distinctions between TVET and ′academic′ education streams have been blurred.[10] This hybridisation has been termed the ′vocationalization of secondary education′, a similar process has happened to a lesser extent in tertiary education.[3]

France and the Netherlands

The baccalauréat professionnel in France, and the middelbaar beroepsonderwijs (MBO) count work experience in the area they are specializing in.[3]

Germany and Austria

Apprenticeships enhanced content within occupational training courses and considerable emphasis has been placed on personal skills.[3]

India

Work education has been included in the primary standards (grades 1–8) to make the students aware of work. At the lower secondary level (grades 9–10) pre-vocational education has been included with the aim to increase students’ familiarity with the world of work.[3]

Republic of Korea

Around 40% of secondary students are currently enrolled in TVET education, in some schools, academic and vocational students share almost 75% of the curriculum.[3]

Russian Federation

A new approach to vocationalization of secondary schooling has been introduced within the framework of general educational reform. This has been guided by the Ministry of Education's strategy of modernization. Vocationalization in the Russian Federation refers to the introduction of profile education at the upper-secondary level (the last two years of schooling, grades 10 and 11) and the process of preparation for profile selection. Profile education provided students with the opportunity to study a chosen area in depth, usually one that would be related to their further study (TVET or academic). Schools could design their own profiles, e.g. science, socio-economics, humanities, and technology, or keep a general orientation curriculum. In preparation for the upper-secondary specialization, a ′pre-profiling′ programme in grade 9 has been introduced to help students make their choices in grade 10.[3]

United States of America

Tech-prep programmes in the United States of America are examples of how the ′blending′ approach was used to help students make the connections between school and work. In year nine, programmes in broad occupational fields such as the health professions, automotive technology, computer systems networking are offered within general technology studies. The programmes continue for at least two years after the end of secondary school, through a tertiary education or an apprenticeship programme, with students achieving an associate degree or certificate by the end of the programme.[3]

Iraq

It is a new experiment in Iraq about TVET, there are three ministries related to TVET in Iraq, Ministry of higher Education and scientific research which represented by the technical universities, Ministry of Education which represented by the vocational education foundation, and Ministry of Labor and Social Guaranty which represented by vocational training centers. Theses associations are trained by UNESCO for the last three years on the main topics and fields of TVET, so they now waiting the Iraqi Perelman to put the suitable law for the TVET Council in Iraq to start it system and control these associations with the required outputs of TVET.

Private sector

Private TVET providers include for-profit and non-profit institutions. Several factors triggered actions to support the expansion of private TVET including the limited capacities of public TVET providers and their low responsiveness to enterprises and trainees. Private TVET providers were expected to be more responsive because they were subject to fewer bureaucratic restrictions than public institutions (particularly in centralized systems). Their presence was expected to help raise quality system-wide, in many developing countries, government budgets constituted a vulnerable and unreliable source of financing for TVET, an important objective was to finance TVET systems by increasing the contribution of beneficiaries, including employers and trainees.[3]

Private TVET provision over since 2005 has become a significant and growing part of TVET in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa.[11][12] In some countries, e.g. Lebanon, enrolments in private TVET institutions have exceeded enrolments in public institutions. In Jordan, private provision at the community college level has been promoted by the government.[12] However, not all experiences has been positive with private proprietary institutions or NGOs, their courses have often been concentrated in professional areas that typically do not require large capital investment, permitting easy entry and exit by private providers from the sector. Quality issues have also emerged, where market information about quality has been unavailable.[3]

Technological advancement and its impact

TVET has an important role to play in technology diffusion through transfer of knowledge and skills. Rapid technological progress has had and continues to have significant implications for TVET. Understanding and anticipating changes has become crucial for designing responsive TVET systems and, more broadly, effective skills policies. The flexibility to adapt the supply of skills to the rapidly, and in some cases radically, changing needs in sectors such as information technology and the green economy has become a central feature of TVET systems. Globally, the skills requirements and qualifications demanded for job entry are rising. This reflects a need for not just a more knowledgeable and skilled workforce, but one that can adapt quickly to new emerging technologies in a cycle of continuous learning.[3]

TVET courses have been created to respond to the diverse ICT needs of learners, whether these are related to work, education or citizenship. New courses have been introduced to address occupational changes in the ICT job market, while many TVET providers have shifted provision towards a blended approach, with significantly more self-directed and/or distance learning. In developed countries, new ICT approaches have been introduced to modernize TVET organizations and to manage administration and finance, including learner records.[3]

Education for all

The Education for All (EFA) movement has had its own implications for TVET at both international and national levels. The third EFA goal lacked precision and measurable targets for TVET, however it called for ensuring ′that the learning needs of all young people and adults are met through equitable access to appropriate learning and life-skills programmes′.[13] This goal had a symbolic value, helping to raise the visibility of TVET and skills development and create a more prominent place for them on the global education policy agenda. The current bulge of young people requiring TVET learning opportunities is partly fuelled by the success of the EFA movement in opening access to basic education, particularly at the primary level. In 2009, 702 million children were enrolled worldwide in primary education, compared with 646 million in 1999.[14][3]

Continuing TVET

Continuing TVET involves ongoing training to upgrade existing skills and to develop new ones and has a much higher profile in ageing societies and knowledge-based economies. Increased recognition of the importance of human capital for economic growth and social development made it necessary to increase learning opportunities for adults in workplaces within the wider context of policies and strategies for lifelong learning.[15][3]

In many countries policy-makers have considered ways to expand workplace learning opportunities for workers and to assess and give credit for knowledge and skills acquired in workplaces. Efforts were geared towards training for workers in companies, encouraged by legislation, financial incentives and contractual agreements.[3]

Challenges

Labour market demands and trends

Following the global financial crisis in 2008, labour markets across the world experienced structural changes that influenced the demand for skills and TVET. Unemployment worsened and the quality of jobs decreased, especially for youth. Gender differentials in labour force participation placed men ahead of women, and skill mismatches deepened. The crisis impacted labour markets adversely and led to deepening uncertainty, vulnerability of employment, and inequality.[16] Furthermore, measures to improve efficiency and profitability in the economic recovery have often led to jobless growth, as happened in Algeria, India and post-apartheid South Africa.[3]

In seeking to address the level of vulnerable employment, TVET systems have focused on increasing the employability of graduates and enhancing their capacity to function effectively within existing vulnerable labour markets and to adjust to other labour market constraints. This has meant enhanced coordination among government departments responsible for TVET and employment policies. It has also created the need for TVET systems to develop mechanisms that identify skills needs early on and make better use of labour market information for matching skills demands and supply. TVET systems have focused more on developing immediate job skills and wider competencies. This has been accomplished by adopting competency-based approaches to instruction and workplace learning that enable learners to handle vulnerable employment, adjust to changing jobs and career contexts, and build their capacity to learn and agility to adapt.[3]

Migration flows

Increasing migration are significant challenges to the national character of TVET systems and qualifications. TVET qualifications are progressively expected not only to serve as proxies for an individual's competencies but to also act as a form of a currency that signals national and international value.[17] TVET systems have been developing mechanisms to enable credible and fair cross-border recognition of skills. In 2007, the ILO identified three types of recognition that TVET system may use: unilateral (independent assessment by the receiving country), mutual (agreements between sending and receiving countries), and multilateral (mostly between a regional grouping of countries). The most prevalent of these is unilateral recognition, which is mostly under the control of national credential evaluation agencies. Countries have been slow to move from input-based skill evaluations to outcome-based methodologies that focus on competencies attained.[18][3]

TVET systems are responding to migration by providing qualifications that can stand the rigour of these recognition systems and by creating frameworks for mutual recognition of qualifications. Regional Qualifications Frameworks such as those in Southern Africa, Europe, Asia and the Caribbean aim to significantly support the recognition of qualifications across borders.[19] These efforts are further supported through the introduction of outcome-based learning methodologies within the broader context of multilateral recognition agreements.[3][18]

Providing broader competencies alongside specialist skills

Skills for economic development include a mix of technical and soft skills. Empirical evidence and TVET policy reviews conducted by UNESCO suggest that TVET systems may not as yet sufficiently support the development of the so-called soft competencies.[20][21][22] Many countries have, however, adopted competency-based approaches as measures for reforming TVET curricula.

The HEART Trust National Training Agency of Jamaica adopted this approach, with a particular emphasis on competency standards and balanced job-specific and generic skills. Competency standards aimed to ensure that the training was linked to industry and was up to date, and that competences were integrated into training programmes, along with the needed knowledge, skills and attitudes. The balancing of skill types was to ensure adequate attention was given to job-specific skills as well as the conceptual and experiential knowledge necessary to enable individuals to grow and develop in the workplace, and more generally in society.[23][3]

Globalization

Globalization of the economy and the consequent reorganization of the workplace require a more adaptable labour force, requiring countries to rethink the nature and role of TVET. Globalization intensifies pressure on the TVET sector to supply the necessary skills to workers involved in globalized activity and to adapt existing skills to rapidly changing needs. As a consequence, there is an increasing requirement for more demand-driven TVET systems with a greater focus on modular and competency-based programmes, as well as on cognitive and transferable skills, which are expected to help people adapt to unpredictable conditions.[3]

Promoting social equity and inclusive workplaces

Preparing marginalized groups of youths and adults with the right skills and helping them make the transition from school to work is part of the problem faced by TVET in promoting social equity. Ensuring that the workplace is inclusive poses numerous policy challenges, depending on the contextual dynamics of inclusion and exclusion, and the capabilities of individuals. For example, the experiences of exclusion by people with disabilities and disadvantaged women may be similar in some ways and different in others. Many individuals experience multiple forms of disadvantage in the workplace, to different degrees of severity, depending on social attitudes and traditions in a specific context or organization. Approaches to inclusiveness in the workplace will therefore vary according to population needs, social diversity and context. To give one example, the Netherlands set about the task of making workplaces more inclusive for low-skilled adults by offering programmes that combine language instruction with work, and in certain cases on-the-job training.[24][3]

A review of employer surveys in Australia, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States of America, reported that employers valued people with disabilities for their high levels of motivation and their diverse perspectives, and found their attendance records to be the same or better than those of other employees.[25] Many employers mentioned that being seen as pro-inclusion was positive for the company or organization's image, an advantage that goes well beyond providing employment opportunities to disadvantaged groups. In many cases, however, social and cultural perceptions are an obstacle to making workplaces more inclusive, and this will require sensitive and concerted attention. Some low- and middle-income countries have sought to address this through legislation. In Tanzania the Disabled Persons (Employment) Act of 1982 established a quota system that stipulates that 2 per cent of the workforce in companies with over fifty employees must be persons with disabilities.[26][3]

The 2012 Education for All Global Monitoring Report concluded that 'all countries, regardless of income level, need to pay greater attention to the needs of young people who face disadvantage in education and skills development by virtue of their poverty, gender or other characteristics'.[27] The report found that several barriers and constraints reduced the success of TVET in meeting social equity demands. First, national TVET policies in most cases failed to address the skills needs of young people living in urban poverty and in deprived rural areas. Second, additional funds were needed to support TVET learning opportunities on a much larger scale. Third, the training needs of disadvantaged young women were particularly neglected. The 2012 EFA Global Monitoring Report also noted that skills training alone was not sufficient for the most disadvantaged of the rural and urban poor.[27] Coherent policies that link social protection, micro-finance and TVET are considered critical for ensuring better outcomes for marginalized groups.[3]

Gender disparities

Recent years have seen rising numbers of young women enrolling in TVET programmes, especially in service sector subjects. At times the challenge is to bring more males into female-dominated streams. However, beyond number games, the real gender parity test that TVET systems are yet to pass is balancing the gender participation in programmes that lead to employability, as well as to decent and high-paying jobs. Gender disparities in learning opportunities, and earnings, are a cause for concern. The persistent gender-typing of TVET requires concerted attention if TVET is to really serve a key facilitative role in shared growth, social equity and inclusive development.[28]

The absence of work, poor quality of work, lack of voice at work, continued gender discrimination and unacceptably high youth unemployment are all major drivers of TVET system reforms from the perspective of social equity. This is an area where TVET systems continue to be challenged to contribute proactively to the shaping of more equitable societies.[28]

Gender equality has received significant international attention in recent years, and this has been reflected in a reduction in gender participation gaps in both primary and secondary schooling. Efforts to analyse and address gender equality in TVET are relevant to other aspects of equity and dimensions of inclusion/exclusion. In almost all parts of the world, the proportion of girls to total enrolment in secondary education defined as TVET is less than for 'general' secondary education.[29][28]

Responses

Bangladesh

Integrating women or men into areas of specialization in which they were previously under-represented is important to diversifying opportunities for TVET. The National Strategy for Promotion of Gender Equality in TVET in Bangladesh set clear priorities and targets for breaking gender stereotypes. The Strategy developed by a Gender Working Group comprising fifteen representatives from government ministries and departments, employers, workers and civil society organizations. It provided an overview of the current status and nature of gender inequalities in TVET, highlighted the priority areas for action, explored a number of steps to promote equal participation of women in TVET, and outlined the way forward.[30][28]

Cambodia

In Cambodia, TVET programmes set out to empower young women in traditional trades by upgrading their skills and technology in silk weaving. This led to the revitalization and reappraisal of a traditional craft by learners and society.[31][28]

The Shanghai Consensus of the Third International Congress on TVET

The Shanghai Consensus of the Third International Congress on TVET made the following recommendations on expanding access and improving quality and equity, including to:

"Improve gender equality by promoting equal access of females and males to TVET programmes, particularly in fields where there is strong labour market demand, and by ensuring that TVET curricula and materials avoid stereotyping by gender."[32][28]

References

- "What is TVET?". UNESCO-UNEVOC. UNESCO. 28 August 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Skills for work and life". UNESCO. UNESCO. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Marope, P.T.M.; Chakroun, B.; Holmes, K.P. (2015). Unleashing the Potential: Transforming Technical and Vocational Education and Training (PDF). UNESCO. pp. 9–10, 41, 43, 47–48, 56–58, 63, 80, 95, 98–103. ISBN 978-92-3-100091-1.

- UNESCO-UNEVOC. "What is TVET?". www.unevoc.unesco.org. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Billet, Stephen (2011). Vocational education : purposes, traditions and prospects. Drodrecht: Springer. ISBN 9789400719538.

- Maclean, Rupert; Herschbach, Dennis R, eds. (2009). International Handbook for the Changing Word of Work. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5281-1.

- McGrath, Simon (2011). "Where to Now for Vocational Eduation and Training in Africa". International Journal of Training and Research. 9 (1). doi:10.5172/ijtr.9.1-2.35.

- Porres, Gisselle Tur; Wildemeersch, Danny; Simons, Maarten (2014). "Reflections on the Emancipatory Potential of Vocational Education and Training Practices: Freire and Rancière in Dialogue". Studies in Continuing Education. 36 (3): 275–289. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2014.904783.

- Hoeckel, Kathrin (2008). "Costs and Benefits of Vocational Education and Training" (PDF). OECD. 17.

- Maclean, R. and Pavlova, M. 2011. Vocationalisation of secondary and higher education: pathways to the world of work. UNESCO-UNEVOC, Revisiting Global Trends in TVET: Reflections on Theory and Practice. Bonn, Germany, UNESCO-UNEVOC International Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training, pp. 40–85.

- Johanson, R. K. and Adams, A. V. 2004. Skills Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC, World Bank.

- ETF and World Bank. 2005. Reforming Technical Vocational Education and Training in the Middle East and North Africa: Experiences and Challenges. Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- World Conference on Education for All. 2000. The Dakar Framework for Action: Meeting our Collective Commitments to Education for All. Paris, UNESCO.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2006. Participation in Formal Technical and Vocational Education and Training Programmes Worldwide: An Initial Statistical Study. Bonn. UNESCO-UNEVOC.

- OECD. 2005. Promoting Adult Learning, Education and Training Policy. Paris, OECD Publishing.

- Bacchetta, M. and Jansen, M. (eds). 2011. Making Globalisation Socially Sustainable. Geneva, ILO and WTO.

- Leney, T. 2009a. Qualifications that Count: Strengthening the Recognition of Qualifications in the Mediterranean Region. Thematic Study. Turin, Italy, ETF. http://www.etf.europa.eu/web. nsf/(RSS)/C125782B0048D6F6C125768200396FB6?OpenDocument&LAN=EN

- Keevy, J. 2011. The recognition of qualifications across borders: the contribution of regional qualifications frameworks. Background paper commissioned by UNESCO. Pretoria, South African Qualifications Authority.

- Keevy, J., Chakroun, B. and Deij, A. 2010. Transnational Qualifications Frameworks. Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union.

- UNESCO. 2013b. Policy Review of TVET in Cambodia. Paris, UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ images/0022/002253/225360e.pdf#xml=http://www.unesco.org/ulis/cgi-bin/ulis.pl?database=&set=53761B39_2_350&hits_rec=2&hits_lng=eng

- UNESCO. 2013c. Policy Review of TVET in Lao PDR. Paris, UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ images/0022/002211/221146e.pdf#xml=http://www.unesco.org/ulis/cgi-bin/ulis.pl?datab ase=&set=53761918_0_231&hits_rec=2&hits_lng=eng

- UNESCO. 2013d. Revue de politiques de formation technique et professionnelle au Benin. Paris, UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002213/221304f.pdf

- HEART Trust NTA. 2009. Policy on competency-based education and training. Draft Concept Paper. Kingston, HEART Trust NTA.

- OECD. 2012. Better Skills Better Jobs Better Lives – OECD: A Strategic Approach to Skills Policies. Paris, OECD Publishing. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/better-skills-better-jobs- better-lives_9789264177338-en

- Employers’ Forum on Disability. 2009. What does the research say are the commercial bene ts? http://www.realising-potential.org/six-building-blocks/commercial/what-researchers- say.html

- SADC and UNESCO. 2011. Final Report: Status of TVET in the SADC Region. Gaborone, SADC, p. 10.

- UNESCO. 2012. Youth and Skills: Putting Education to Work. EFA Global Monitoring Report. Paris, UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002180/218003e.pdf

- Marope, P.T.M; Chakroun, B.; Holmes, K.P. (2015). Unleashing the Potential: Transforming Technical and Vocational Education and Training (PDF). UNESCO. pp. 20, 53, 85, 163. ISBN 978-92-3-100091-1.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2012. Global Education Digest 2012. Opportunities Lost: The Impact of Grade Repetition and Early School Leaving. Montreal, UIS.

- ILO. 2012b. Draft National Strategy for Promotion of Gender Equality in TVET. Dhaka, ILO. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---ilo-dhaka/ documents/publication/wcms_222688.pdf

- Salzano, E. 2005. Technology-Based Training for Marginalised Girls. Paris, UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2012. Shanghai Consensus. Recommendations of the third international congress on TVET: Transforming TVET: Building Skills for Work and Life. Shanghai, 14–16 May 2012. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002176/217683e.pdf