Stegodon

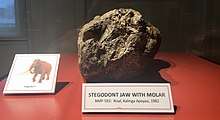

Stegodon, meaning "roofed tooth" (from the Ancient Greek words στέγω, stégō, 'to cover', + ὀδούς, odoús, 'tooth') because of the distinctive ridges on the animal's molars, is a genus of the extinct subfamily Stegodontinae of the order Proboscidea. It was assigned to the family Elephantidae (Abel, 1919), but has also been placed in the Stegodontidae (R. L. Carroll, 1988).[1] Stegodonts were present from 11.6 million years ago (Mya) to the late Pleistocene, with unconfirmed records of localized survival until 4,100 years ago. Fossils are found in Asian and African strata dating from the late Miocene; during the Pleistocene, they lived across large parts of Asia and East and Central Africa, and in Wallacea as far east as Timor.[1][2][3]

| Stegodon | |

|---|---|

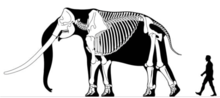

| Stegodon skeleton at the Gansu Provincial Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | †Stegodontidae |

| Genus: | †Stegodon Falconer, 1847 |

| Species | |

| |

A review of 130 papers written about 180 different sites with proboscidean remains in southern China revealed Stegodon to have been more common than Asian elephants; the papers gave many recent radiocarbon dates, the youngest being 2,150 BCE (4,100 BP).[2] However, Turvey et al. (2013) reported that one of the faunal assemblages including supposed fossils of Holocene Stegodon (from Gulin, Sichuan Province) is actually late Pleistocene in age; other supposed fossils of Holocene stegodonts were lost and their age cannot be verified. The authors concluded that the latest confirmed occurrences of Stegodon from China are from the late Pleistocene, and that its Holocene survival cannot be substantiated.[4]

Morphology

Size

Stegodon was one of the largest proboscideans, along with more derived genera. S. zdansky is known from an old male (50+) from the Yellow River that is 3.87 m (12.7 ft) tall and would have weighed approximately 12.7 tonnes (12.5 long tons; 14.0 short tons) in life. It had a humerus 1.21 m (4.0 ft) long, a femur 1.46 m (4.8 ft) long, and a pelvis 2 m (6.6 ft) wide.[5]

Dwarfism

S. florensis insularis is an extinct subspecies of Stegodon endemic to the island of Flores, Indonesia, and an example of insular dwarfism. The direct ancestor of S. florensis insularis is the larger-bodied S. florensis florensis, from Early Pleistocene and early Middle Pleistocene sites on Flores.[6] Remains of S. florensis insularis are known from the cave of Liang Bua.

Similar to modern-day elephants, stegodonts were likely good swimmers,[7][8] as their fossils are frequently encountered on Asian islands (such as Sulawesi, Flores, Timor, Sumba in Indonesia; Luzon and Mindanao in the Philippines; Taiwan; and Japan), all locations not connected by land bridges with the Asian continent even during periods of low sea level (during the cold phases of the Pleistocene). A general evolutionary trend in large mammals on islands is island dwarfing. The smallest dwarf species known is S. sumbaensis from Sumba,[9] with an estimated body mass of 250 kg.[10] The slightly larger S. sondaari, known from Early Pleistocene layers on the Indonesian island of Flores, had an estimated body weight of between 355 and 650 kg.[10] Another estimate gives a shoulder height of 1.2 m (3.9 ft) and a weight of 350–400 kg (770–880 lb).[5] A medium- to large-sized stegodont, S. florensis, with a body weight of about 1,700 kg, appeared about 850,000 years ago, and then also evolved into a dwarf form, S. f. insularis, with an estimated body mass of about 570 kg.[10][6] Another estimate gives a shoulder height of 2 m (6.6 ft) and a weight of 2 t (2.0 long tons; 2.2 short tons).[5] The latter was contemporaneous with, and hunted by, the dwarf hominin Homo floresiensis, and disappeared about 49,600 years ago,[11] earlier than initially thought.[12] Dwarf stegodonts were believed to be the main prey of the still-extant Komodo dragon before modern humans introduced their modern main prey in its range, banded pig, rusa deer, and water buffalo.[13]

Taxonomy

In the past, stegodonts were believed to be the ancestors of the true elephants and mammoths, but currently they are believed to have no modern descendants. Stegodon may be derived from Stegolophodon, an extinct genus known from the Miocene of Asia. Stegodon is considered to be a sister group of elephants and mammoths. Some taxonomists consider the stegodonts a subfamily of the Elephantidae. Both Stegolophodon and primitive elephants were derived from the Gomphotheriidae. The most important difference between Stegodon and (other) Elephantidae can be observed in the molars. Stegodont molars consist of a series of low, roof-shaped ridges, whereas in elephants, each ridge has become a high-crowned plate. Furthermore, stegodont skeletons are more robust and compact than those of elephants.

In Bardia National Park in Nepal, a population of Indian elephants, possibly due to inbreeding, exhibits many Stegodon-like morphological features. These primitive features are considered recent mutations rather than atavisms.[14][15]

Fossils of the small, specialized stegodont S. aurorae are found in the Osaka Plain, Japan, and date from around 2 million to 7 million years ago. This species possibly evolved from S. shinshuensis.[16]

Phylogeny

The following cladogram shows the placement of the genus Stegodon among other proboscideans, based on hyoid characteristics:[17]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- PaleoBiology Database: Stegodon, basic info

- H. Saegusa, "Comparisons of Stegodon and Elephantid Abundances in the Late Pleistocene of Southern China Archived 2006-05-08 at the Wayback Machine", The World of Elephants -- Second International Congress, (Rome, 2001), 345-349.

- Louys, Julien; Price, Gilbert J.; O’Connor, Sue (2016-03-10). "Direct dating of Pleistocene stegodon from Timor Island, East Nusa Tenggara". PeerJ. 4: e1788. doi:10.7717/peerj.1788. ISSN 2167-8359.

- Samuel T. Turvey, Haowen Tong, Anthony J. Stuart and Adrian M. Lister (2013). "Holocene survival of Late Pleistocene megafauna in China: a critical review of the evidence". Quaternary Science Reviews. 76: 156–166. Bibcode:2013QSRv...76..156T. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.06.030.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014.

- Van Den Bergh, G.D., Aweb, R.D., Morwoodc, M.J., Sutiknab, T., Jatmikob and Saptomo, E. W. 2008. The youngest stegodon remains in Southeast Asia from the Late Pleistocene archaeological site Liang Bua, Flores, Indonesia. Quaternary International 182(1): 16-48.

- Simpson, G. (1977). Too Many Lines; The Limits of the Oriental and Australian Zoogeographic Regions. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 121(2), 107-120. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/986523

- Bird, Michael I.; Condie, Scott A.; O’Connor, Sue; O’Grady, Damien; Reepmeyer, Christian; Ulm, Sean; Zega, Mojca; Saltré, Frédérik; Bradshaw, Corey J. A. (2019). "Early human settlement of Sahul was not an accident". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 8220. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42946-9. PMC 6579762. PMID 31209234.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turvey, Samuel T.; Crees, Jennifer J.; Hansford, James; Jeffree, Timothy E.; Crumpton, Nick; Kurniawan, Iwan; Setiyabudi, Erick; Guillerme, Thomas; Paranggarimu, Umbu; Dosseto, Anthony; van den Bergh, Gerrit D. (2017-08-30). "Quaternary vertebrate faunas from Sumba, Indonesia: implications for Wallacean biogeography and evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284 (1861): 20171278. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.1278. PMC 5577490. PMID 28855367.

- van der Geer, Alexandra A. E.; van den Bergh, Gerrit D.; Lyras, George A.; Prasetyo, Unggul W.; Due, Rokus Awe; Setiyabudi, Erick; Drinia, Hara (2016). "The effect of area and isolation on insular dwarf proboscideans". Journal of Biogeography. 43 (8): 1656–1666. doi:10.1111/jbi.12743.

- Sutikna, Thomas; Tocheri, Matthew W.; Morwood, Michael J.; Saptomo, E. Wahyu; Jatmiko; Awe, Rokus Due; Wasisto, Sri; Westaway, Kira E.; Aubert, Maxime; Li, Bo; Zhao, Jian-xin (April 2016). "Revised stratigraphy and chronology for Homo floresiensis at Liang Bua in Indonesia". Nature. 532 (7599): 366–369. doi:10.1038/nature17179. ISSN 0028-0836.

- Van Den Bergh, G. D.; Rokhus Due Awe; Morwood, M. J.; Sutikna, T.; Jatmiko; Wahyu Saptomo, E. (May 2008). "The youngest Stegodon remains in Southeast Asia from the Late Pleistocene archaeological site Liang Bua, Flores, Indonesia". Quaternary International. 182 (1): 16–48. Bibcode:2008QuInt.182...16V. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.02.001.

- Diamond, Jared M. (1987). "Did Komodo dragons evolve to eat pygmy elephants?". Nature. 326 (6116): 832.

- Ben S. Roesch. "Living Stegodont or Genetic Freak?". Archived from the original on 16 July 2012.

- Norton, Charlie (2010-10-14). "In search of the Beast of Bardia". ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- Yoshikawa, S; Kawamura, Y.; Taruno, H. "Land bridge formation and proboscidean immigration into the Japanese Islands during the quaternary". Journal of Geosciences, Osaka City University. 50: 1–6.

- Shoshani, J.; Tassy, P. (2005). "Advances in proboscidean taxonomy & classification, anatomy & physiology, and ecology & behavior". Quaternary International. 126–128: 5–20. Bibcode:2005QuInt.126....5S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.011.

| Wikispecies has information related to Stegodon |