Slavic Native Faith's identity and political philosophy

In the Russian intellectual milieu, Slavic Native Faith (Rodnovery) presents itself as a carrier of the political philosophy of nativism/nationalism/populism (narodnichestvo),[1] intrinsically related to the identity of the Slavs and the broader group of populations with Indo-European origins. The scholar Robert A. Saunders has found that Rodnover ideas are very close to those of Eurasianism, the current leading ideology of the Russian state.[2] Others have found similarities of Rodnover ideas with those of the Nouvelle Droite (European New Right).[3] Rodnovery typically gives preeminence to the rights of the collectivity over the rights of the individual,[4] and Rodnover social values are conservative.[5] Common themes are the opposition to cosmopolitanism, liberalism, and globalisation,[6] as well as Americanisation and consumerism.[7]

| Part of a series on |

| Slavic Native Faith |

|---|

|

|

Denominations Not strictly related ones:

|

|

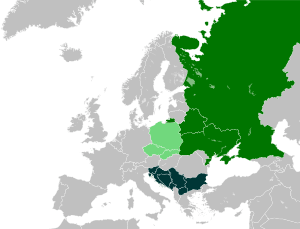

Spread |

|

Sources

|

The scholar Kaarina Aitamurto has defined Rodnovers' applied political systems as forms of grassroots democracy, or as a samoderzhavie ("people ruling themselves") system, based on the ancient Slavic model of the veche (assembly) of the elders, similar to ancient Greek democracy. They generally propose a political system in which power is entrusted to assemblies of consensually-acknowledged wise men, or to a single wise individual.[8]

On the level of geopolitics, to the "unipolarity", the "unipolar" world, created by the mono-ideologies (the Abrahamic religions and their other ideological products) and led by the United States of America-dominated West, the Rodnovers oppose the idea of "multipolarity", of a world of many power centres, well represented by the "Russian Way". In their view, while the unipolar world is characterised by the materialism and selfish utilitarianism of the West, the multipolar world represented by Russia is characterised by spirituality, ecology, humanism and true equality. The idea of Russian multipolarity against Westernising unipolarity is popular among Russian intellectuals, and among Rodnovers it was first formally enunciated in the Russian Pagan Manifesto, published in 1997 by four Russian Rodnover leaders.[9]

The historian Marlène Laruelle has observed that Rodnovery is in principle a decentralised movement, with hundreds of groups coexisting without submission to a central authority. Therefore, socio-political views can vary greatly from one group to another, from one adherent to another, ranging from apoliticism, to left-wing, to right-wing positions. Nevertheless, Laruelle says that the most politicised right-wing groups are the most popularly known, since they are more vocal in spreading their ideas through the media, organise anti-Christian campaigns, and even engage in violent actions.[10] Aitamurto observed that the different wings of the Rodnover movement "attract different kinds of people approaching the religion from quite diverging points of departure".[11] Aitamurto and Victor Shnirelman have also found that the lines between right-wing, left-wing and apolitical Rodnovers is blurry.[12]

The 1997 Russian Pagan Manifesto mentions, as sources of inspiration, three figures famous for their strong nationalism and conservatism: Lev Gumilyov, Igor Shafarevich, and the Iranian Ruhollah Khomeini. In 2002, the Bittsa Appeal was promulgated by Rodnovers less political in their orientation, and among other things it explicitly condemned extreme nationalism within Rodnovery. A further Rodnover political declaration, not critical towards nationalism, was the Heathen Tradition Manifest published in 2007.[13]

Origins of the Slavs

The notion that modern Rodnovery is closely tied to the historical religion of the Slavs is a very strong one among practitioners.[14] There is no evidence that the early Slavs, a branch of the Indo-Europeans, ever conceived of themselves as a unified ethno-cultural group.[15] There is an academic consensus that the Proto-Slavic language developed from about the second half of the first millennium BCE in an area of Central and Eastern Europe bordered by the Dnieper basin to the east, the Vistula basin to the west, the Carpathian Mountains to the south, and the forests beyond the Pripet basin to the north.[16]

Over the course of several centuries, Slavic populations migrated in northern, eastern, and south-western directions.[16] In doing so, they branched out into three sub-linguistic families: the East Slavs (Ukrainians, Belarussians, Russians), the West Slavs (Poles, Czechs, Slovaks), and the South Slavs (Slovenes, Serbs, Croats, Macedonians, and Bulgarians).[16] The belief systems of these Slavic communities had many affinities with those of neighbouring linguistic populations, such as the Balts, Thracians, and Indo-Iranians.[16] Vyacheslav Ivanov and Vladimir Toporov studied the origin of ancient Slavic themes in the common substratum represented by Proto-Indo-European religion and what Georges Dumézil studied as the "trifunctional hypothesis". Marija Gimbutas, instead, found Slavic religion to be a clear result of the overlap of Indo-European patriarchism and pre-Indo-European matrifocal beliefs. Boris Rybakov emphasised the continuity and complexification of Slavic religion through the centuries.[17]

Political ideologies

Veche democracy

.jpg)

Many Russian Rodnover groups are strongly critical of democracy, modern liberal democracy, which they see as a degenerate form of government that leads to "cosmopolitan chaos". According to Shnirelman they favour instead political models of a centralised state led by a strong leader.[18] Aitamurto, otherwise, characterises the political models proposed by Rodnovers as based on their interpretation of the ancient Slavic community model of the veche (assembly), similar to the ancient Germanic "thing".[19] Nineteenth- and twentieth-century intellectuals often interpreted the veche as an anti-hierarchic and democratic model, while later Soviet Marxist tended to identify it as "pre-capitalist democracy". The term already had ethnic and national connotations, which were underlined by nineteenth-century Slavophiles, and nationalist circles in the last decades of the Soviet Union and from the 1990s onwards.[20]

Many Rodnover groups call their organisational structure veche. Aitamurto finds that it proves to be useful in what she terms as Rodnvery's "democratic criticism of democracy" (of liberal democracy). According to her, the veche as interpreted by Rodnovers represents a vernacular form of governance similar to ancient Greek democracy. According to the view shared by many Rodnovers, while liberal democracy ends up in chaos because it is driven by the decisions of the masses, who are not wise; the veche represents a form of "consensual decision-making" of assemblies of wise elders, and power is exercised by wise rulers. Ynglists call this model samoderzhavie, "people ruling themselves".[21] Western liberal ideas of freedom and democracy are traditionally perceived by Russian eyes as "outer" freedom, contrasting with Slavic "inner" freedom of the mind; in Rodnovers' view, Western liberal democracy is "destined to execute the primitive desires of the masses or to work as a tool in the hands of a ruthless elite", being therefore a mean-spirited "rule of demons".[22] Aitamurto also describes many Rodnovers' political philosophy as elitism, in which not everyone is reputed as having the same decision ability; the most conservative Rodnovers espouse the ideal that "the opinion of a prostitute cannot have the same weight as the opinion of a professor".[23]

In these ideas of grassroots democracy which comes to fruition in a wise governance, Aitamurto sees an incarnation of the traditional Russian challenge of religious structures and alienated governance—such as autocratic monarchy and totalitarian communism—for achieving a personal relationship with the sacred, which is at the same time a demand of social solidarity and responsibility. She presents the interpretation of the myth of Perun who slashes the snake guilty of theft, provided by Russian volkhv Velimir, as symbolising the ideal relationship and collaboration between the ruler and the people, with the ruler serving the people who have chosen him by acting as an authority who provides them with order, and in turn is respected by the people with loyalty for his service.[24] Some Rodnovers interpret the veche in ethnic terms, thus as a form of "ethnic democracy", in the wake of similar concepts found in the Nouvelle Droite.[3]

Nationalism

The scholar Scott Simpson states that Slavic Native Faith is fundamentally concerned with ethnic identity.[25] This easily develops into forms of nationalism,[26] and has often been characterised as ethnic nationalism.[27] Aitamurto suggested that Russian Rodnovers' conceptions of nationalism encompass three main themes: that "the Russian or Slavic people are a distinct group", that they "have—or their heritage has—some superior qualities", and that "this unique heritage or the existence of this ethnic group is now threatened, and, therefore, it is of vital importance to fight for it".[28] According to Shnirelman, ethnic nationalist and racist views are present even in those Rodnovers who do not identify as politically engaged.[29] He also noted that the movement is "obsessed with the idea of origin",[29] and most Rodnover groups will permit only Slavs as members, although there are a few exceptions.[30] There are Rodnover groups that espouse less radical positions of nationalism, such as cultural nationalism or patriotism.[31]

Anti-miscegenation

Some Rodnover groups are against miscegenation (the mixing of different races). In its founding statement from 1998, the Federation of Ukrainian Rodnovers led by the Ukrainian Rodnover leader Halyna Lozko declared that many of the world's problems stem from the "mixing of ethnic cultures", something which it claims has resulted in the "ruination of the ethnosphere", which they regard as an integral part of the Earth's biosphere.[32] Rodnovers generally conceive ethnicity and culture as territorial, moulded by the surrounding natural environment (ecology).[33]

Lev Sylenko, founder of the Ukrainian branch of Rodnovery known as the Native Ukrainian National Faith, taught that humanity was naturally divided up into distinct ethno-cultural groups, each with its own life cycle, religiosity, language, and customs, all of which had to spiritually progress in their own way.[34] Many Ukrainian Rodnovers emphasise a need for ethnic purity and oppose what they regard as the "culturally destructive" phenomena of liberal globalisation.[6]

Ethnic purity is also central to the denomination of the Ynglists,[35] who abhor miscegenation as unhealthy, and abhor as well what are perceived as perverted sexual behaviours and the consumption of alcohol and drugs. According to the Ynglists, all of these are evil influences which come from the degenerating West and threaten Russia. In order to counterweigh them, the Ynglists promote policies such as the "creation of beneficial descendants" (sozidanie blagodetel'nogo potomstva).[36] Some Rodnovers have demanded to make mixed-race marriages illegal in their countries.[30]

Ethno-states

There are Russian Rodnovers who promote the common views of Russian nationalism: some seek an imperialist policy that would expand Russia's territory across Europe and Asia, while others seek to reduce the area controlled by the Russian Federation to only those areas with an ethnic Russian majority.[37] The place of nationalism, and of ethnic Russians' relationship to other ethnic groups inhabiting the Russian Federation, has been a key issue of discussion among Russian Rodnovers.[38] Some express xenophobic views and encourage the removal of those regarded as "aliens" from Russia, namely those who are Jewish or have ethnic origins in the Caucasus.[37]

For these Rodnovers, ethnic minorities are viewed as the cause of social injustice in Russia.[30] According to Shnirelman, given that around 20% of the Russian Federation is not ethnically Russian, the ideas of ethnic homogeneity embraced by many Russian Rodnovers could only be achieved through ethnic cleansing.[30] Aitamurto notes that the territorial release of several of the majority non-Russian republics of Russia and autonomous okrugs of Russia would result in the same reduction of ethnic minorities in Russia without any need for violence whatsoever, which is the approach called for by peaceful Russian Rodnovers.[37]

Antisemitism, Nazism and socialism

Various Russian practitioners are openly antisemitic,[39] and express conspiracy theories claiming that Jews control Russia's economic and political elite.[37] For example, the Ukrainian leader Halyna Lozko produced a prayer manual titled Pravoslav in which "Don't get involved with Jews!" was listed as the last of ten "Pagan commandments".[40] Similar views are also present within the Polish Rodnover community.[41]

Shnirelman observed that many Russian Rodnovers deny or downplay the racist and Nazi elements within their community.[42] There are, however, various Rodnover groups in Russia which are openly inspired by Nazi Germany.[43] Among those groups that are ideologically akin to Neo-Nazism, the term "Nazi" is rarely embraced, in part due to the prominent role that the Soviet Union played in the defeat of Nazi Germany.[44] The volkhv Dobroslav—who holds a position of high respect within Russia's Rodnover community—calls his political idea a new "Russian national socialism" or "Pagan socialism", entailing "harmony with nature, a national sovereignty and a just social order".[45]

Some Rodnovers claim that those who adopt such extreme right-wing perspectives are not true Rodnovers because their interests in the movement are primarily political rather than religious.[42] According to the scholars Hilary Pilkington and Anton Popov, Cossack Rodnovers generally eschew Nazism and racial interpretations of the concept of "Aryan".[46]

Apoliticism

Trends of de-politicisation of the Russian Rodnover community have been influenced by the introduction of anti-extremist legislation,[47] and the lack of any significant political opposition to the United Russia government of Vladimir Putin.[4] Simpson noted that in Poland, there has been an increasing trend to separate the religion from explicitly political activities and ideas during the 2010s.[48] The Russian Circle of Pagan Tradition recognises Russia as a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural state, and has developed links with other religious communities in the country, such as practitioners of Mari Native Faith.[49] Members of the Circle of Pagan Tradition prefer to characterise themselves as "patriots" rather than "nationalists" and seek to avoid any association with the idea of a "Russia for the Russians".[50] Aitamurto and Shizhenskii suggested that expressions of ultra-nationalism were considered socially unacceptable at one of the largest Rodnover events in Russia, the Kupala festival outside Maloyaroslavets.[51]

Influence on already-existing political formations and incidents

Rodnover ideas and symbols have also been adopted by many Russian nationalists—including in the Russian skinhead movement[52]—not all of whom embrace Rodnovery as a religion.[53] Some of these far-right groups merge Rodnover elements with others adopted from Germanic Heathenry and from Russian Orthodox Christianity.[54] The Rodnover denomination of Ynglism is characterised by Aitamurto as less politically goal-oriented than other Rodnover movements.[55] However, the Russian scholar of religion Vladimir B. Yashin of the Department of Theology and World Cultures of Omsk State University wrote in 2001 that Ynglism had close ties with the regional branch of the far-right Russian National Unity of Alexander Barkashov, whose members provide security and order during the mass gatherings of the Ynglists.[56]

A number of young practitioners of Slavic Native Faith have been detained on terrorism charges in Russia;[29] between 2008 and 2009, teenaged Rodnovers forming a group called the Slavic Separatists conducted at least ten murders and planted bombs across Moscow targeting Muslims and non-ethnic Russians.[57]

Rodnovers' historical and identity views founding their political ideologies

Many Rodnovers legitimise their ideas by magnifying their Slavic ancestors and according them great cultural achievements.[58] Aitamurto stated that one of early Rodnovery's "most characteristic features" was its "extremely imaginative and exaggerated descriptions of Russia's history".[59] Similarly, the scholar Vladimir Dulov noted that the "interpretations of history" articulated by Bulgarian practitioners are "rather fantastic".[60] However, Aitamurto and Alexey Gaidukov later noted that the "wildly imaginative" ideas typical of the 1980s were in decline, and that—within Russia at least—"a more realistic attitude" to the past was "gaining ground" in the twenty-first century.[61] Some Rodnovers openly combat theories such as that of the Vseyasvetnaya gramota ("Universal alphabet", a discipline which, similarly to Jewish Kabbalah, sees Cyrillic and Glagolitic scripts as mystical and magical ways to communicate with God, and as instruments to see past events and foresee future ones) as "New Age" and claim that reliance on them discredits the Slavic Native Faith movement.[62] Views on history vary between different strains of Rodnovery; for instance, in Ukraine the Native Ukrainian National Faith espouses a mythologised Slavic history, while broader Rodnovery is more in line with the mainline narrative.[63]

The Book of Veles

.jpg)

Many Rodnovers regard the Book of Veles as a holy text,[65] and as a genuine historical document.[66] Its composition is attributed by Rodnovers to ninth- or early tenth-century Slavic priests who wrote it in Polesia or the Volyn region of modern north-west Ukraine. Russian interpreters, however, locate this event much further east and north. The Book contains hymns and prayers, sermons, mythological, theological and political tracts, and historical narrative. It tells the wandering, over about one thousand and five hundred years of the ancestors of the Rus', identified as the Oryans (the book's version of the word "Aryan"), between the Indian subcontinent and the Carpathian Mountains, with modern Ukraine ultimately becoming their main homeland. Ivakhiv says that this territorial expansiveness is the main issue that makes historians wary of the Book.[67] Aitamurto described the work as a "Romantic description" of a "Pagan Golden Age".[59]

The fact that many scholars outspokenly reject the Book as a modern, twentieth-century composition has added to the allure that the text has for many Slavic Native Faith practitioners. According to them, such criticism is an attempt to "suppress knowledge" carried forward either by Soviet-style scientism or by "Judaic cosmopolitan" forces. A number of Ukrainian scholars defend the truthfulness of the Book, including literary historian Borys Yatsenko, archaeologist Yuri Shylov, and writers Valery Shevchuk, Serhy Plachynda, Ivan Bilyk, and Yuri Kanyhin. These scholars claim that criticism of the Book primarily comes from Russians interested in promoting a Russocentric view of history which sets the origin of all East Slavs in the north, while the Book shows that southern Rus' civilisation is much older, and nearer to Ukrainians themselves, West Slavs, South Slavs and the eastern Indo-European composers of the Vedas, than to Russians.[67] For many Ukrainian Rodnovers, the Book provides them with a cosmology, ethical system, and ritual practices that they can follow, and confirms their belief that the ancient Ukrainians had a literate and advanced civilisation prior to the arrival of Christianity.[65] Other modern literary works that have influenced the movement, albeit on a smaller scale, include The Songs of the Bird Gamayon, Koliada's Book of Stars, The Song of the Victory on Jewish Khazaria by Sviatoslav the Brave or The Rigveda of Kiev.[68]

Aryans and polar mysticism

Some Rodnovers believe that the Slavs are a race distinct from other ethnic groups.[28] According to them, the Slavs are the directest descendants of ancient Aryans, whom they equate with the Proto-Indo-Europeans.[69] Some Rodnovers espouse esoteric teachings which hold that these Aryans have spiritual origins linked to astral patterns of the north celestial pole (cf. circumpolar stars), around the pole star, such as the Great Bear, or otherwise to the Orion constellation.[28] According to further teachings the Aryans originally dwelt at the geographic North Pole, where they lived until the weather changed and they moved southwards.[70]

Other Rodnovers emphasise that the Aryans germinated in Russia's southern steppes.[71] In claiming an Aryan ancestry, Slavic Native Faith practitioners can legitimise their cultural borrowing from other ethnic groups who they claim are also Aryan descendants, such as the Germanic peoples or those of the Indian subcontinent.[72] Another belief held by some Rodnovers is that many ancient societies—including those of the Egyptians, Hittites, Sumerians, and Etruscans—were created by Slavs, but that this has been concealed by Western scholars eager to deny the Slavic peoples knowledge of their true history.[71]

Eschatology

Some Russian Rodnovers believe that Russia has a messianic role to play in human history and eschatology; Russia would be destined to be the final battleground between good and evil or the centre of post-apocalyptic civilisation which will survive the demise of the Western world.[7] At this point—they believe—the entire Russian nation will embrace Rodnovery.[73] The Russian Rodnover leader Aleksandr Asov believes that the Book of Veles will be the "geopolitical weapon of the next millennium" through which an imperial, Eurasian Russia will take over the spiritual and political leadership of the world from the degenerated West.[67] Other Rodnovers believe that the new spiritual geopolitical centre will be Ukraine.[74]

In 2006, a conference of the European New Right was held in Moscow under the title "The Future of the White World", with participants including Rodnover leaders such as Ukraine's Halyna Lozko and Russia's Pavel Tulaev. The conference focused on ideas for the establishment in Russia of a political entity that would function as a new epicentre of white race and civilisation, enshrining the "religion, philosophy, science and art" that emanate from the "Aryan soul",[75]:90–91 either taking the form of Guillaume Faye's "Euro-Siberia", Aleksandr Dugin's "Eurasia", or Pavel Tulaev's "Euro-Russia".[75]:84–85 According to Tulaev, Russia enshrines in its own name the essence of the Aryans, one of the etymologies of Rus being from a root that means "bright", whence "white" in mind and body.[75]:86 Such eschatological and racial beliefs are explicitly rejected by other Rodnovers, like the Russian Circle of Pagan Tradition.[50]

Academic influence

Although their understanding of the past is typically rooted in spiritual conviction rather than in arguments that would be acceptable within contemporary Western scientific paradigms, many Rodnovers seek to promote their beliefs about the past within the academia.[61] For instance, in 2002 Serbian practitioners established Svevlad, a research group devoted to historical Slavic religion which simulated academic discourse but was "highly selective, unsystematic, and distorted" in its examination of the evidence.[76] In Poland, archaeologists and historians have been hesitant about any contribution that Slavic Native Faith practitioners can make to understandings of the past.[77] Similarly, in Russia, many of the larger and more notable universities refuse to give a platform to Rodnover views, but smaller, provincial institutions have sometimes done so.[61]

Within Russia, there are academic circles in which a "very vivid trend of alternative history" is promoted; these circles share many of the views of Slavic Native Faith practitioners, particularly regarding the existence of an advanced, ancient Aryan race from whom ethnic Russians are descended.[78] For instance, Gennady Zdanovich, the discoverer of Arkaim (an ancient Indo-European site) and leading scholar about it and broader Sintashta culture, is a supporter of the views of the history of the Aryans that are popular within Rodnovery and is noted for his spiritual teachings about how sites like Arkaim were ingenious "models of the universe". For this, Zdanovich has been criticised by publications of the Russian Orthodox diocese of Chelyabinsk, especially in the person of colleague archaeologist Fedor Petrov, who "begs the Lord to forgive" for the corroboration that archaeology has provided to the Rodnover movement.[79]

See also

References

Citations

- Aitamurto 2016, p. 141.

- Saunders 2019, p. 566.

- Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 235; Aitamurto 2008, p. 6.

- Shnirelman 2013, p. 63.

- Laruelle 2012, p. 308.

- Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 223.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 189.

- Aitamurto 2008, pp. 2–5.

- Aitamurto 2016, p. 114.

- Laruelle 2012, p. 296.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 205.

- Shnirelman 2013, p. 63; Aitamurto 2016, pp. 48–49.

- Aitamurto 2016, pp. 48–49.

- Simpson & Filip 2013, p. 39.

- Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 211; Lesiv 2017, p. 144.

- Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 211.

- Ivakhiv 2005c, p. 211.

- Shnirelman 2012.

- Aitamurto 2008, pp. 2–3.

- Aitamurto 2008, p. 3.

- Aitamurto 2008, pp. 4–5.

- Aitamurto 2008, pp. 6-7.

- Aitamurto 2008, p. 5.

- Aitamurto 2008, pp. 5–6.

- Simpson 2013, p. 118.

- Črnič 2013, p. 189.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 195; Lesiv 2013b, p. 131.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 187.

- Shnirelman 2013, p. 64.

- Shnirelman 2013, p. 72.

- Aitamurto 2006, pp. 201–202.

- Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 229.

- Laruelle 2012, p. 307.

- Ivakhiv 2005b, pp. 225–226.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 206.

- Aitamurto 2016, p. 88.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 190.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 185.

- Laruelle 2008, p. 284.

- Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 234.

- Simpson 2017, pp. 72–73.

- Shnirelman 2013, p. 62.

- Laruelle 2008, p. 296.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 197.

- Shnirelman 2000, p. 18; Shnirelman 2013, p. 66.

- Pilkington & Popov 2009, p. 273.

- Shnirelman 2013, p. 62; Shizhenskii & Aitamurto 2017, p. 114.

- Simpson 2017, p. 71.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 201.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 202.

- Shizhenskii & Aitamurto 2017, p. 129.

- Shnirelman 2013, p. 67; Shizhenskii & Aitamurto 2017, pp. 115–116.

- Aitamurto & Gaidukov 2013, p. 156.

- Shnirelman 2013, p. 68.

- Aitamurto 2016, p. 51.

- Maltsev, V. A. (18 November 2015). "Расизм во имя Перуна поставили вне закона". Nezavisimaya Gazeta. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020.

- Shnirelman 2013, p. 70; Skrylnikov 2016.

- Lesiv 2013b, p. 137.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 186.

- Dulov 2013, p. 206.

- Aitamurto & Gaidukov 2013, p. 155.

- Laruelle 2012, pp. 306–307; Aitamurto & Gaidukov 2013, p. 159.

- Lesiv 2013a, p. 93.

- "Дощьки (The Planks)". Жар-Птица (Firebird Monthly Magazine). San Francisco, January 1954. pp. 11–16.

- Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 219.

- Laruelle 2008, p. 285.

- Ivakhiv 2005a, p. 13.

- Laruelle 2008, p. 291.

- Shnirelman 2017, p. 90.

- Aitamurto 2006, p. 187; Laruelle 2008, p. 292.

- Laruelle 2008, p. 292.

- Shnirelman 2017, p. 103.

- Laruelle 2008, p. 29.

- Ivakhiv 2005a, p. 15.

- Arnold, Richard; Romanova, Ekaterina (2013). "The White World's Future: An Analysis of the Russian Far Right". Journal for the Study of Radicalism. 7 (1): 79–108. ISSN 1930-1189.

- Radulovic 2017, pp. 60–61.

- Simpson 2013, p. 120.

- Laruelle 2008, p. 295.

- Petrov, Fedor (29 June 2010). "Наука и неоязычество на Аркаиме (Science and Neopaganism at Arkaim)". Proza.ru. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

Sources

- Aitamurto, Kaarina (2006). "Russian Paganism and the Issue of Nationalism: A Case Study of the Circle of Pagan Tradition". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 8 (2): 184–210.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2008). "Egalitarian Utopias and Conservative Politics: Veche as a Societal Ideal within Rodnoverie Movement". Axis Mundi: Slovak Journal for the Study of Religions. 3: 2–11.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2016). Paganism, Traditionalism, Nationalism: Narratives of Russian Rodnoverie. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781472460271.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aitamurto, Kaarina; Gaidukov, Alexey (2013). "Russian Rodnoverie: Six Portraits of a Movement". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 146–163. ISBN 9781844656622.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Črnič, Aleš (2013). "Neopaganism in Slovenia". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 182–194. ISBN 9781844656622.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dulov, Vladimir (2013). "Bulgarian Society and Diversity of Pagan and Neopagan Themes". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 195–212. ISBN 9781844656622.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ivakhiv, Adrian (2005a). "In Search of Deeper Identities: Neopaganism and 'Native Faith' in Contemporary Ukraine". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 8 (3): 7–38. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2005.8.3.7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2005b). "The Revival of Ukrainian Native Faith". In Michael F. Strmiska (ed.). Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. pp. 209–239. ISBN 9781851096084.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laruelle, Marlène (2008). "Alternative Identity, Alternative Religion? Neo-Paganism and the Aryan Myth in Contemporary Russia". Nations and Nationalism. 14 (2): 283–301.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2012). "The Rodnoverie Movement: The Search for Pre-Christian Ancestry and the Occult". In Brigit Menzel; Michael Hagemeister; Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal (eds.). The New Age of Russia: Occult and Esoteric Dimensions. Kubon & Sagner. pp. 293–310. ISBN 9783866881976.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lesiv, Mariya (2013a). The Return of Ancestral Gods: Modern Ukrainian Paganism as an Alternative Vision for a Nation. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773542624.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2013b). "Ukrainian Paganism and Syncretism: 'This Is Indeed Ours!'". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 128–145. ISBN 9781844656622.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2017). "Blood Brothers or Blood Enemies: Ukrainian Pagans' Beliefs and Responses to the Ukraine-Russia Crisis". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 133–156. ISBN 9781137570406.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pilkington, Hilary; Popov, Anton (2009). "Understanding Neo-paganism in Russia: Religion? Ideology? Philosophy? Fantasy?". In George McKay (ed.). Subcultures and New Religious Movements in Russia and East-Central Europe. Peter Lang. pp. 253–304. ISBN 9783039119219.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Radulovic, Nemanja (2017). "From Folklore to Esotericism and Back: Neo-Paganism in Serbia". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 19 (1): 47–76. doi:10.1558/pome.30374.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saunders, Robert A. (2019). "Rodnovery". Historical Dictionary of the Russian Federation (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 565–567. ISBN 9781538120484.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shizhenskii, Roman; Aitamurto, Kaarina (2017). "Multiple Nationalisms and Patriotisms among Russian Rodnovers". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 109–132. ISBN 9781137570406.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shnirelman, Victor A. (2000). "Perun, Svarog and Others: Russian Neo-Paganism in Search of Itself". The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology. 21 (3): 18–36.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2012). "Русское Родноверие: Неоязычество и Национализм в Современной России" [Russian native faith: neopaganism and nationalism in modern Russia]. Russian Journal of Communication. 5 (3): 316–318. doi:10.1080/19409419.2013.825223.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2013). "Russian Neopaganism: From Ethnic Religion to Racial Violence". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 62–71. ISBN 9781844656622.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2015). "Perun vs Jesus Christ: Communism and the emergence of Neo-paganism in the USSR". In Ngo, T.; Quijada, J. (eds.). Atheist Secularism and its Discontents. A Comparative Study of Religion and Communism in Eurasia. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 173–189. ISBN 9781137438386.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2017). "Obsessed with Culture: The Cultural Impetus of Russian Neo-Pagans". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 87–108. ISBN 9781137570406.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, Scott (2013). "Polish Rodzimowierstwo: Strategies for (Re)constructing a Movement". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 112–127. ISBN 9781844656622.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2017). "Only Slavic Gods: Nativeness in Polish Rodzimowierstwo". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 65–86. ISBN 9781137570406.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, Scott; Filip, Mariusz (2013). "Selected Words for Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 27–43. ISBN 9781844656622.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skrylnikov, Pavel (20 July 2016). "The Church Against Neo-Paganism". Intersection. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)