Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce

Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, OD (née Fraser, born December 27, 1986) is a Jamaican track and field sprinter. Born and raised in Kingston, Jamaica, she rose to prominence at the 2008 Olympics after becoming the first Caribbean woman to win gold in the 100 m.[2] In 2012, she became the third woman in history to successfully defend an Olympic 100 m title.[3][4] After winning bronze in 2016, she also became the first woman in history to win 100 m medals at three consecutive Olympics.[5] In 2017, she took a one-year break from athletics to have her first child.[6][7] At the 2019 World Championships, she became the oldest female sprinter (at age 32)[8] and second mother ever to win 100 m gold at a global championship.[6][9]

.jpg) Fraser-Pryce in 2015 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Jamaican | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 27 December 1986 Kingston, Jamaica | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Residence | Kingston, Jamaica | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.52 m (5 ft 0 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 52 kg (115 lb) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Country | Jamaica | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | Track and field | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Event(s) | Sprint | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Club | MVP Track & Field Club | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coached by | Stephen Francis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Achievements and titles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal best(s) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In addition to her two Olympic 100 m titles, Fraser-Pryce is also the only sprinter in history to become world champion over 100 m four times—2009, 2013, 2015 and 2019.[10][11] The only woman to achieve a "sprint triple" at a single World Championship (gold in the 100 m, 200 m and 4 × 100 m),[12] she is also the only female sprinter to reign as world champion at 60 m, 100 m, 200 m and 4 × 100 m relay at the same time.[13] Fraser-Pryce is one of the most decorated athletes in World Championship history with 11 medals, including nine gold and two silver. In 2013, she was named World Athlete of the Year.[13]

With over a decade in athletics, Fraser-Pryce has won more global 100 m titles than any other female sprinter in history.[14][11] She has posted the most sub-10.80 s clockings in history with 14, as well as the second-most sub-11 s clockings (with over 50).[6][15] Nicknamed the "Pocket Rocket"[13][10] for her petite five-feet frame and explosive block starts, her personal best of 10.70 seconds is the joint fourth fastest of all time.[16] Due to her achievements and consistency, many publications and sports analysts, including former Olympian Michael Johnson,[17][7] have described her as the greatest female sprinter of all time.[18][5][19] World Athletics called her “the greatest female sprinter of her generation".[20]

Early life and career beginnings

Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce (née Fraser) grew up in the violent, inner city community of Waterhouse, near Kingston, describing her own family background as poor.[21] Her mother Maxine Simpson, a former athlete, was a single parent who worked as a street vendor.[22][23][24] When Fraser-Pryce started running at age 10, she did so barefoot.[25] In her senior year at Wolmer's High School for Girls, she competed in the famous Jamaican Schools Championships, winning the 100 m at aged 16.[21] A product of the fierce rivalry of grassroots athletics in Jamaica, she described these championships as intense, and at times, hostile.[21] However, she admitted that it was "something they got used to".[21]

Fraser-Pryce started taking track seriously at age 21, after she met Coach Stephen Francis at the University of Technology.[26] At the time, Francis was the head coach at the MVP (Maximising Velocity and Power) Track Club, one of two such elite clubs in Jamaica (the other being the Racers Track Club, home to sprinters Usain Bolt and Yohan Blake).[26] She began her career specializing in the 100 m, but did not qualify for the individual event for the 2007 World Championships.[27] However, she was selected as part of the Jamaican 4 x 100 m relay team that year, earning a silver medal by running in the heats.[20][27]

Career

2008–2009: Olympic and world champion

At the Jamaican Athletics Championships in 2008, Fraser-Pryce's top-three finish in the 100 m denied Veronica Campbell-Brown, the reigning world champion, a spot on the Olympic team.[27][28] Barely known beyond the local athletics scene, many considered Fraser-Pryce too inexperienced for the Olympics and petitioned unsuccessfully to have her swapped in favour of Campbell-Brown.[27] Despite mounting pressure, the JAAA (Jamaica's governing body for athletics) upheld its rule permitting only the top-three finishers on the Olympic team. Fraser-Pryce, ranked 70th in the world that year, went to the 2008 Olympics hopeful but without the burden of expectation: "I went in just wanting to do well. So there was no pressure and nobody expected anything of me and I was able to compete better, relaxed and be my best."[21]

At the Olympics, held at the Beijing National Stadium, she placed first in her 100 m heats and semifinals.[12] In the final, she led the way to a Jamaican sweep of the medals, capped by a second place tie for Sherone Simpson and Kerron Stewart (both women clocked 10.98 s for silver; no bronze was awarded).[2][12] Fraser-Pryce’s winning time of 10.78 s[2] not only shattered her personal best, it was the second fastest Olympic 100 m time in history.[28] Alongside Stewart, Simpson and Campbell-Brown, she also took part in the 4 × 100 m relay, placing first in the heats and qualifying as fastest for the final. However, they did not finish the race in the final due to a mistake in the baton exchange.[2][12]

Now a more confident young sprinter, 23-year-old Fraser-Pryce reaffirmed her status on the global stage with another surprising win at the 2009 World Championships, held in Berlin.[27] Taking time off in April to have her appendix removed, she bounced back to win the world title in August, a year to the day after her Olympic triumph in Beijing.[12] Ahead of the championships, teammate Kerron Stewart held the world lead of 10.75 s and was the favourite for gold.[29] However, Fraser-Pryce emerged as a frontrunner with 10.79 s in the semifinal, the fastest ever non-final time at a global championship.[29] In the 100 m final, she made a flying start, holding off a late challenge from Stewart to claim the victory in a new personal best of 10.73 s.[29] Stewart matched her own personal best of 10.75 s for silver and American Carmelita Jeter won bronze in 10.90 s.[29] The winning time of 10.73 s improved on Merlene Ottey's Jamaican record (10.74 s) and was the joint third fastest in history at the time.[12][29] With the victory, Fraser-Pryce joined American Gail Devers as the only women to reign as world and Olympic 100 m champion at the same time.[29]

Fraser-Pryce closed the championships by earning a second gold medal as part of Jamaica's 4 × 100 m relay team, alongside Stewart, Simone Facey and Aleen Bailey.[18] Later that year, she competed in the now defunct IAAF World Athletics Final, winning silver behind Jeter in the 100 m.[30]

2010 Suspension and 2011 Worlds

In May 2010, a urine sample taken at the Shanghai Diamond League was found to contain Oxycodone.[31] Oxycodone is a painkiller that is not considered to improve performance, nor does the WADA Code consider it a masking agent for other drugs.[32] Her coach Stephen Francis reportedly recommended the painkiller for a toothache, and she neglected to properly declare it, in what she has described as a clerical error.[33] Fraser-Pryce later stated, "[I'm] supposed to set examples – so whatever it is I put in my body it's up to me to take responsibility for it and I have done that".[33] She served a six-month suspension, resuming competition in January 2011.[33][34]

Fraser-Pryce married long-term boyfriend Jason Pryce in 2011, changing her name from Fraser to Fraser-Pryce.[33] She had a slow start to the season, coming off her suspension and battling a recurring calf injury that hindered her preparation for the 2011 World Championships.[35][36] As the defending 100 m champion from 2009, she earned automatic qualification for the upcoming championships in Daegu, and did not compete at the Jamaican National Championships.[35] Not considered the favourite for the gold, she held a season’s best of 10.95 s, the sixth fastest time of the year.[37][38]

In the 100 m final, Fraser-Pryce did not achieve her usual fast start and finished fourth in 10.99 s.[39] Carmelita Jeter won gold in 10.90 s, while Veronica Campbell-Brown and Tobagonian Kelly-Ann Baptiste collected silver and bronze in 10.97 s and 10.98 s respectively.[39] It remains Fraser-Pryce's only appearance at a World Championship where she did not win 100 m gold.[40] She later ran the lead leg on Jamaica's 4 x 100 m relay team, winning silver behind the United States.[20]

2012 Olympics and 2013 sprint triple

Beginning with her first Olympic win in 2008, Fraser-Pryce had been at the forefront of a booming sprint rivalry between Jamaica and the United States.[41][42] At the Beijing Olympics four years ago, Jamaica had secured five of a possible six sprinting medals, with Fraser-Pryce and Campbell-Brown winning the 100 m and 200 m respectively, and Usain Bolt dominating the men's 100 m, 200 m, and 4 x 100 m (the relay medal was later rescinded).[41][43] Jamaica’s success continued through the 2009 and 2011 World Championships, punctuated by Bolt's record-breaking performance at the 2009 event.[44][45] For the upcoming Summer Olympics, the rivalry had once again taken centre stage, with the American team seeking to regain its former dominance over the sprints.[46][43][47]

After an inconsistent start to the 2012 season, Fraser-Pryce won the sprint double at the Jamaican Olympic Trials in June.[48] In the 100 m, she set a new personal best of 10.70 s, which improved on the national record she set in 2009 and landed her at number-four on the all-time list.[48][49] In the 200 m, she also set a personal best of 22.10 s.[48] While preparing for the Olympics, she was also completing her Bachelor of Science degree at the University of Technology in Jamaica. Heading into the Olympics, Fraser-Pryce was aiming to defend her title from 2008 after failing to medal in the 100 m final at the 2011 World Championships. However, she faced strong competition from American Carmelita Jeter,[47] the reigning world champion and the second fastest woman of all time.[3][50]

At the Olympics, Fraser-Pryce qualified for the 100 m final as second fastest overall behind Jeter.[50] In the final she was quickest from the blocks, leaning at the finish line for a narrow victory ahead of Jeter to defend the title.[3][50] Jeter finished 0.03 seconds behind in 10.78, with Campbell-Brown third in 10.81 s.[51][52] Fraser-Pryce's 10.75 s was the second fastest in Olympic history at the time;[34] in fact, the race itself was the fastest ever run at the Olympics, with an unprecedented seven women clocking 11 seconds or faster.[51] With her win, Fraser-Pryce joined Americans Gail Devers and Wyomia Tyus as the only women to ever defend an Olympic 100 m title.[53][25]

In the 200 m final, Fraser-Pryce lowered her personal best to 22.09 s for silver behind American Allyson Felix, who won gold in 21.88 s.[54] She also ran the first leg in the 4 × 100 m relay alongside Campbell-Brown, Sherone Simpson and Kerron Stewart. The team won silver in 41.41 s (a new national record) behind the United States' world record time of 40.82 s.[55][18]

Overall, Jamaica had another strong showing at the Olympics, winning four of a possible six gold medals in the sprints.[56] In addition to Fraser-Pryce retaining her title, Bolt also continued his unbroken streak on the men's side, leading a top-two finish for Jamaica in the 100 m, a sweep of the medals in the 200 m,[57] and a new world record in the 4 x 100 m relay.[58] Closing out the 2012 season, Fraser-Pryce lost to Jeter at the Samsung Diamond League at the end of August.[59]

The following year, Fraser-Pryce continued to show her consistency. At the 2013 World Championships, held in Moscow, she matched Usain Bolt in achieving a rare "sprint triple"—gold in the 100 m, 200 m and 4 x 100 m.[60][12] For the 2013 season, she refocused her training to emphasize the 200 m.[61] For her, this involved conditioning, endurance and recovery, but also learning to mentally embrace the longer sprint: "I had to change my mindset for the 200 and make it more like the 100...I’ve worked more on my 200 this year than the 100 and have had to develop the same love for both.”[61] She kickstarted the season with a 100 m victory in January, clocking 11.47 s on home soil in Kingston.[60] In May and June, she enjoyed Diamond League wins in both the 100 m and 200 m in Doha, Shanghai and Eugene.[60] For the second consecutive year, she won the 200 m title at the Jamaican Championships, in a world-leading 22.13 s.[60]

Looking to regain the 100 m world title she lost in 2011, an in-form Fraser-Pryce arrived at the championships with world-leading times in both the 100 m (10.77 s) and 200 m (22.13 s).[60] In the 100 m final, she bolted from the blocks, streaming away to a dominating win in 10.71 s, the fastest time of the year.[62] Her 0.22-second margin of victory was the largest in World Championship history.[63][64] Murielle Ahoure of the Ivory Coast won silver in 10.93 s, while Jeter, the defending world champion, collected bronze in 10.94 s.[62] By claiming a second world title, Fraser-Pryce became the only woman to win the 100 m twice at both the Olympics (2008, 2012) and the World Championships (2009, 2013).[63][24] In the 200 m final, she stormed to a comfortable victory in 22.17 s, earning her first global title over the distance.[61] As the anchor for Jamaica's 4 × 100 m relay team, she secured her third win in a new championship record of 41.29 s.[65][18]

For the 2013 season, Fraser-Pryce boasted the three fastest times of the year in the 100 m and the two fastest in the 200 m.[60] She won six Diamond League races throughout the season (four in the 100 m and two in the 200 m) to clinch the Diamond League titles for both distances.[60] Owing to her achievements on the track throughout the season, she was named the IAAF World Athlete of the Year.[13][66]

2014 Indoor debut and third world title

On the heels of a successful 2013 season, Fraser-Pryce made her World Indoor Championships debut in Sopot, Poland the next year.[13] Early into the season, she clocked 7.11 s in an outdoor 60 m race in Kingston (Jamaica does not have indoor facilities). Months later in Birmingham, she finished second in her only 60 m loss of the season to world 100 m and 200 m silver medallist Murielle Ahoure.[13]

In Sopot, she won both her heat and semifinal in 7.12 s and 7.08 s respectively.[13] In the final, she had her usual quick start and finished ahead of Ahoure in a world-leading 6.98 s.[13] Her winning time, which she achieved with no specific preparation for the 60 m, was the fastest since 1999[67] and the seventh fastest in history at the time.[13][12] In claiming gold, she gave Jamaica its fourth 60 m win in the 16-year history of the championships.[13] She also became the first woman in history to hold world titles at the 60 m, 100 m, 200 m and 4 x 100 m at the same time.[13]

For the 2015 season, Coach Francis decided that Fraser-Pryce would not attempt to defend her 200 m title at the upcoming World Championships.[68][69] Speaking at a meet in Paris, she explained that although the 200 m had improved aspects of her 100 m, her coach believed she had lost some her signature explosiveness from the blocks.[68] As a result, she would focus on sharpening the 100 m for the upcoming championships and attempt the sprint double at the 2016 Olympics.[68][69]

At the 2015 World Championships, Fraser-Pryce was hoping to make history as the first woman to win three 100 m world titles.[23] There was also speculation that she would attempt to break Marion Jones' 16-year-old championship record (and her own personal best) of 10.70 s.[70] Entering the championships, she headed the 100 m world rankings with 10.74 s, and qualified as fastest overall in the semifinal.[71] In the 100 m final, she led from the gun, fending off a late challenge from Dutch sprinter Dafne Schippers to win in 10.76 s.[14][71] Although happy for the win, Fraser-Pryce was dissatisfied with her time, and in a post-race interview stated, "I'm getting tired of 10.7s...I definitely think a 10.6 is there. Hopefully I will get it together."[71]

Fraser-Pryce also anchored the women's 4 × 100 m team, consisting of Veronica Campbell-Brown, Natasha Morrison and protege Elaine Thompson, to gold.[18] Their 41.07 s broke the championship record for the second consecutive time.[72] She capped her 2015 season with Diamond League wins in Zürich and Padova, clocking 10.93 s and 10.98 s respectively.[73]

2016 Olympics and split from coach

With a record three world titles and two Olympic titles, Fraser-Pryce had matched Usain Bolt medal for medal in the 100 m throughout their career.[4][71] With the upcoming 2016 Olympics, she set her sights on becoming the first sprinter to win a third successive Olympic 100 m title.[4][23] Her season would not go as planned, however, after a lingering toe injury impeded her training and preparation, forcing her to take significant time off for the first time in her career.[4][74] After missing several planned races, she finished last in her first outing of the season in 11.18 s.[75]

– Fraser-Pryce reflecting on her difficult 2016 season.[11]

In the weeks before the Olympics, Fraser-Pryce struggled to reach form, posting 11.25 s in Italy and 11.06 s at the London Grand Prix.[38][76] Meanwhile, her training partner Elaine Thompson emerged as top contender for Olympic gold, with a world-leading 10.70 s at the Jamaican Olympic Trials.[77][78] In a season that saw at least five of her rivals run 10.80 s or faster, Fraser-Pryce's season's best of 10.93 s was only the eighth fastest of the year.[38][78]

In Rio, Fraser-Pryce qualified as joint fastest for the final with Thompson, in a new season's best time of 10.88 s.[79] She was in notable pain after her semifinal, crying and limping off the track.[80] In the final, she battled to the finish in a season’s best 10.86 s to win bronze.[81] Thompson won gold in 10.71 s, while American Tori Bowie earned silver in 10.83 s.[81][82] Fraser-Pryce later collected a silver medal as part of the women's 4 × 100 metres relay team.[18] Although she fell short of defending her Olympic title, she described her 100 m bronze as her "greatest medal ever", given her challenging season.[80]

After the Olympics, reports circulated that Fraser-Pryce was parting ways with longtime coach Stephen Francis, whom she shared with Thompson.[83] Francis confirmed these rumours in August 2016, stating that Fraser-Pryce was unhappy with their preparation for the Olympics and told him that she had lost confidence in his training programme.[84][83] He also stated that she was dissatisfied with the lack of improvements to her timings over the years, specifically in lowering her 10.70 s personal best from 2012.[84] However, with no official statement, Fraser-Pryce and her coach reconciled and she resumed training at the MVP Track Club in November of that year.[85]

2018 return and fourth world title

.jpg)

In early 2017, Fraser-Pryce announced that she was pregnant and would not be defending her title at the 2017 World Championships in London.[40] She went into labour while watching the world 100 m final that year, and gave birth the next day via emergency C-section.[7][8] She returned to competition less than a year later, describing her journey back as both physically and mentally challenging: "My stomach would be in pain...I couldn’t [train] abdominals properly. I [wondered] whether my body would allow me to put the level of work in to get it done.”[7][10]

Fraser-Pryce took to the international circuit for several Diamond League meets in Europe, all while breastfeeding for the first 15 months.[8] After eight races, she posted her first sub-11 s timing with 10.98 in London.[86] She ended her 2018 season in August with a fifth-place finish at the Toronto NACAC Championships, clocking 11.18 s.[87] Despite expectations that she would retire, she publicly promised a major comeback.[7]

– Fraser-Pryce on her victory at the 2019 World Championships.[88]

At the Jamaican Championships in June 2019, Fraser-Pryce finished second to double Olympic champion Elaine Thompson in both the 100 m and the 200 m.[11] Although Thompson won by a comfortable margin in the 200 m, the 100 m final ended in a dead heat, with both sprinters sharing the world-leading time of 10.73 s.[89] Fraser-Pryce’s 10.73 in this race became the fastest non-winning time in history.[90] Fraser-Pryce returned to the top of women's sprinting for the 2019 season, running at close to personal best times in the 100 m,[5] and recording three of the five fastest times of the year.[40][11] In August, she won 200 m gold at the 2019 Pan American Games, in a new championship record of 22.43 s.[91][11] However, after losing to Thompson in June, the two did not meet until the 2019 World Championships, in one of the event's most highly anticipated showdowns.[40][11]

In Doha, Fraser-Pryce cruised to 10.80 s in the 100 m heats, the fastest first-round time in World Championships history.[92] She followed with 10.81 s in the semifinal, the fastest qualifying time ahead of the final.[88] In the 100 m final, she outpaced the field from the start, powering away to her fourth title in a world-leading 10.71 s—her fastest time since 2013.[10][93] (Thompson finished fourth.)[10] With this achievement, she became the oldest woman and second mother ever to win a 100 m world or Olympic title.[8][9][10] Fraser-Pryce admitted to taking particular satisfaction in her win, calling it "a victory for motherhood".[94][95] She added a second gold medal at the championships by running the second leg of the Jamaican 4 x 100 m relay team, her ninth world championship title overall.[18] She had also planned to contest the 200 m, but later withdrew.[96]

In February 2020, Fraser-Pryce won the 60 m at the Muller Indoor Athletics Grand Prix, clocking 7.16 s.[97] It was her first Indoor competition since she won gold in Sopot back in 2014.[97] She is currently training for the upcoming 2021 Olympics and announced that she will retire after the 2022 World Championships.[18][7]

Off the track

In November 2012, Fraser-Pryce graduated from the University of Technology with her Bachelor of Science in Child and Adolescent Development. In 2016, she announced that she would be pursuing a Master of Science in Applied Psychology at the University of the West Indies.[4] A committed Christian,[98] she married Jason Pryce in 2011,[33] and announced her pregnancy in early 2017.[99] On her Facebook she wrote, "All my focus heading into training for my 2017 season was on getting healthy and putting myself in the best possible fitness to successfully defend my title in London 2017, but ... here I am thinking about being the greatest mother I can be."[99] On 7 August 2017, she and her husband welcomed a son named Zyon.[98]

Sponsorship, charities and business

Fraser-Pryce has signed sponsorship deals with Digicel, GraceKennedy and Nike.[100] To promote her chase for Olympic glory in 2016, Nike released a series of promotional videos of her training sessions for the 100 m.[101]

Fraser-Pryce has supported many causes throughout her career. She was named as the first UNICEF National Goodwill Ambassador for Jamaica on 22 February 2010.[102] That year, she was also named Grace Goodwill Ambassador for Peace in a partnership with Grace Foods and not-for-profit organisation PALS (Peace and Love in Society).[103] She also created the Pocket Rocket Foundation, a scheme which supports high school athletes in financial need.[98][100]

Known for frequently changing her hairstyle during track season, she launched a hair salon named Chic Hair Ja in 2013.[104]

Legacy and achievements

– Retired Olympian Michael Johnson on Fraser-Pryce's 2019 win.[17]

In 2019, the Olympic Channel described Fraser-Pryce as the most successful[11] and one of the greatest ever in women's sprinting: "Two consecutive Olympic titles in the 100m, four world titles in the same distance, six Olympic medals in total, eleven World Championship medals overall, nine of which are gold, including in the 200m...: Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce is one of, if not the, greatest female sprinters of all time."[18] In 2020, Track & Field News ranked her as the top female 100 m sprinter of the 2010s decade, as well as the fifth greatest in the 200 m.[105] The same publication ranked her at number-two in the 100 m for the 2000s decade.[105] Sean Ingle of The Guardian lauded her achievements after the 2019 World Championships, asserting that her win gave her "legitimate claim to be considered the greatest ever."[106] Writing for CNN, Ben Church also admired her longevity, pointing out that her 2019 win in Doha came 11 years after her first Olympic title, with her winning time just 0.01 seconds shy of her seven-year-old personal best.[107][108] Fraser-Pryce has registered 14 sub-10.80 s clockings in the 100 m—more than any other female sprinter in history.[106] She also has 51 sub-11 s clockings, second only to Merlene Ottey.[15] The fastest mother in history, she is also the oldest female sprinter to win a global 100 m title.[89]

My secret is just staying humble...know who you are as a person and athlete and just continue to work hard.

— Fraser-Pryce on her longevity in track and field.[107]

.jpg)

Despite her success, her profile on a global scale has been largely eclipsed by countryman Usain Bolt.[4][23] On the eve of the 2016 Olympics, The Washington Post alluded to this disparity with the headline "A Jamaican will go for a third gold medal in Rio — and it’s not who you think".[23] In the article, writer Ross Kenneth Urken argued that although she had dominated her sport for nearly a decade, her rise to prominence occurred "remarkably under the radar, especially compared with Bolt’s."[23] Likewise, CNN wrote that Fraser-Pryce matched Bolt "medal for medal over 100 m...Somehow, that isn't common knowledge."[4] In a post-race interview at the 2012 Olympics, she was asked how famous she was in Jamaica.[3] She joked, "I'm famous enough that they ask me about Usain.”[3] Although she has been vocal about the gender gap in athletics, Fraser-Pryce has insisted that she has never felt overshadowed.[25][109] She also asserted that the near-unattainable 100 m world record (set by American Florence Griffith Joyner[25]) and the lack of special times in women's sprinting have contributed to the disparity: "I have always said it's a man's world...[but] I think it has a lot to do with the times as well. When you have male athletes [running]... 9.5s as opposed to female athletes running 10.8s constantly, there is no 'wow' to the event."[69]

After the 2019 championships, sports writer Steve Keating declared Fraser-Pryce the new face of athletics, adding that her "golden personality" and "human interest" resonated with fans, marketers and sponsors.[94] He also saw the birth of her son and her determination to return to the top as compelling dimensions to her legacy.[94]

In 2019, Fraser-Pryce published the children's book I Am a Promise, based on the life lessons she learned growing up and competing as an athlete.[110]

Awards and recognition

In 2008, Fraser-Pryce was honoured with the Order of Distinction for her achievements in athletics.[111] In October 2018, she was also honoured with a statue at the Jamaica National Stadium in Kingston, Jamaica.[112] During the ceremony, Minister of Sports Olivia Grange hailed her a role model for young girls and a Jamaican "modern-day hero".[112]

The recipient of many accolades in Jamaica, she has won the JAAA's Golden Cleats Award for Female Athlete of the Year four times: 2009, 2012, 2013 and 2015.[113] She has also received the Jamaican Sportsperson of the Year award four times, in 2012, 2013, 2015 and 2019.[114]

On the international scene, she has been nominated for the Laureus World Sports Award for Sportswoman of the Year five times: 2010, 2013, 2014, 2016 and 2019.[115] After her 2013 season, she was named IAAF World Athlete of the Year, becoming the first Jamaican woman to win since Merlene Ottey in 1990. In accepting her award, she exclaimed, "I'm shocked and excited. It's something that has been a dream of mine."[116][13]

Technique and running style

Under the guidance of her coach Stephen Francis, Fraser-Pryce honed her technique to become, according to World Athletics, “the greatest female sprinter of her generation”.[20][11] She stated that none of her technique came naturally, and that when she began competing, she ran with poor knee lift and an exaggerated forward lean.[101][26] To help improve her knee height and posture, Coach Francis incorporated more high-knee drills into her training.[101] By 2008, she had sharpened her start, including her first stride, the placement of her arms and the different phases of the sprint.[101] Describing her mind-muscle connection while running, she explained, "You feel all of your phases. Because of how the body is, you can feel it, like a sixth sense. So I focus on nailing each phase properly, and if I’m able to nail each phase properly, then I know that’s history.”[101]

Fraser-Pryce's trademark is her explosive starts (drive phase), which have earned her the nickname "Pocket Rocket."[14][3][62] Her style involves “bolting to the lead”[117] with maximum velocity and then "maintaining her position through to the finish.”[117] Jon Mulkeen of World Athletics described her starts as "devastating...her best weapon,"[62] while Steve Landell of the same publication declared, "her ability to shift her legs over the first five metres remains the envy of the world."[29] Studying her performance in the world 100 m final in 2009 (when she clocked 10.73 s), sports scientists Rolf Graubner and Eberhard Nixdorf reported her 30 m split at 4.02 s, which they estimated to be at the level of male sprinters with a performance ability in the 10.40 s – 10.60 s range.[118]

At 1.52 m (5 ft) tall, Fraser-Pryce is more petite than most female sprinters.[119][26] She noted that early into her career, fellow athletes and coaches told her she was "too short and shouldn't think about running fast."[26] A prototypical stride rate runner, she relies on cadence and a high stride frequency (i.e. leg speed) in her races, although she also has "well developed" stride length.[117][118] On average, she covers the 100 m within 50 strides, and has a cadence of about 286 steps per minute.[120] Her world 100 m final from 2009 took 49.58 strides — equivalent to two metres per step, with her longest stride of 2.2 metres seen over the last 20 metres of her race.[118] Her peak stride frequency (between 20–40 metres in the race) was also calculated at 4.91 times per second.[120][118]

Season's best and rankings

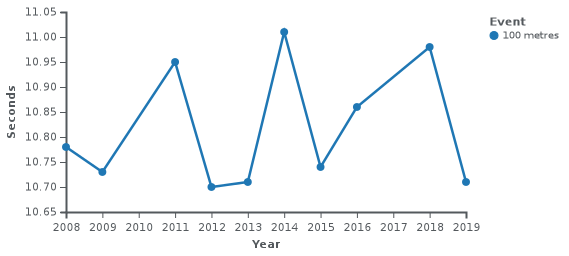

Fraser-Pryce's season's best in the 100 m since 2008.[121]

Season's best 100 m and 200 m, with world rank in parentheses.[121]

| Year | 100 metres | 200 metres |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 10.78 (1)[122] | 22.15 (6)[123] |

| 2009 | 10.73 (2) | 22.58 (18) |

| 2010 | – | – |

| 2011 | 10.95 (6) | 22.59 (14)[124] |

| 2012 | 10.70 (1) | 22.09 (2)[125] |

| 2013 | 10.71 (1) | 22.13 (1) |

| 2014 | 11.01 (8)[126] | 22.53 (13)[127] |

| 2015 | 10.74 (1) | 22.37 (17) |

| 2016 | 10.86 (8) | – |

| 2017 | – | – |

| 2018 | 10.98 (10)[128] | – |

| 2019 | 10.71 (1) | 22.22 (7) |

International competitions

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Event | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representing | |||||

| 2002 | Central American and Caribbean Junior Championships (U-17) |

Bridgetown, Barbados | 4th | 200 m | 25.24 (−1.0 m/s) |

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 45.33 CR | |||

| 2005 | CARIFTA Games (U-20) | Bacolet, Trinidad and Tobago | 3rd | 100 m | 11.73 (+0.9 m/s) |

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 44.53 | |||

| 2007 | World Championships | Osaka, Japan | 2nd | 4×100 m relay | 42.70 SB |

| 2008 | Olympic Games | Beijing, China | 1st | 100 m | 10.78 PB (±0.0 m/s) |

| DNF | 4×100 m relay | Dropped baton | |||

| 2009 | World Championships | Berlin, Germany | 1st | 100 m | 10.73 NR (+0.1 m/s) |

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 42.06 | |||

| 2011 | World Championships | Daegu, Korea | 4th | 100 m | 10.99 (−1.4 m/s) |

| 2nd | 4×100 m relay | 41.70 NR | |||

| 2012 | Olympic Games | London, Great Britain | 1st | 100 m | 10.75 (+1.5 m/s) |

| 2nd | 200 m | 22.09 PB (−0.2 m/s) | |||

| 2nd | 4×100 m relay | 41.41 NR | |||

| 2013 | World Championships | Moscow, Russia | 1st | 100 m | 10.71 WL (−0.3 m/s) |

| 1st | 200 m | 22.17 (−0.3 m/s) | |||

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 41.29 CR | |||

| 2014 | World Indoor Championships | Sopot, Poland | 1st | 60 m | 6.98 WL PB |

| Commonwealth Games | Glasgow, Scotland | 1st | 4×100 m relay | 41.83 GR | |

| 2015 | World Championships | Beijing, China | 1st | 100 m | 10.76 (−0.3 m/s) |

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 41.07 CR | |||

| 2016 | Olympic Games | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | 3rd | 100 m | 10.86 SB (+0.5 m/s) |

| 2nd | 4×100 m relay | 41.36 SB | |||

| 2018 | NACAC Championships | Toronto, Canada | 5th | 100 m | 11.18 |

| 2nd | 4×100 m relay | 43.33 | |||

| 2019 | World Relays | Yokohama, Japan | 3rd | 4×200 m relay | 1:33.21 |

| Pan American Games | Lima, Peru | 1st | 200 m | 22.43 | |

| World Championships | Doha, Qatar | 1st | 100 m | 10.71 WL (+0.1 m/s) | |

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 41.44 WL | |||

Circuit wins

- Diamond League (100 m; other events specified in parenthesis)

- World Indoor Tour (60 m)

- Glasgow: 2020

National titles

- Jamaican Championships

- 2009: 100 m

- 2012: 100 m, 200 m

- 2013: 200 m

- 2015: 100 m

- Jamaican U18 Championships

- 2002: 200 m

Personal bests

| Type | Event | Time | Date | Place | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outdoor | 100 metres | 10.70 (+0.6) | 29 June 2012 | Kingston, Jamaica | NR, 4th of all time |

| 200 metres | 22.09 (−0.2) | 8 August 2012 | London, United Kingdom | ||

| 400 metres | 54.93 | 5 March 2011 | Kingston, Jamaica | ||

| Indoor | 60 metres | 6.98 | 9 March 2014 | Sopot, Poland | 8th of all time |

- All information taken from World Athletics profile.

References

- Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce at World Athletics

- Phillips, Michael (18 August 2008). "Olympics: Fraser on front line as Jamaica sweep the women's 100m". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Epstein, David (4 August 2012). "A unique style leads Fraser-Pryce to her second straight 100 title". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Williams, Ollie (18 July 2016). "Rio 2016: Can Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce beat Usain Bolt to Olympic history?". CNN. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Hunter, Dave (July 2019). "An Encore For Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce". Track & Field News. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Brown, Oliver (29 September 2019). "Dina Asher-Smith wins world 100m silver as Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce takes title". The Telegraph. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Bloom, Ben (19 December 2019). "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce exclusive interview: 'Everyone said I would retire after I had a baby'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "Mother's Day: Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, Allyson Felix win historic golds at world champs". NBC Sports. 29 September 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Kelsall, Christopher (26 December 2019). "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce to double down at 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games". Athletics Illustrated. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Rowbottom, Mike (29 September 2019). "Report: women's 100m - IAAF World Athletics Championships Doha 2019". World Athletics. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Jiwani, Ror (26 September 2019). "Who will be the world's fastest woman in Doha". Olympic Channel. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Fraser-Pryce Set for Lift-off Again". Olympic Channel. 19 July 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Bamford, Nicola (10 March 2014). "Fraser-Pryce: "I just came here and wasn't prepared for the 60m"". World Athletics. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Landells, Steve (24 August 2015). "Report: women's 100m final – IAAF World Championships, Beijing 2015". World Athletics. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Lawrence, Hubert (28 July 2019). "50 And Counting! - Fraser-Pryce Hits Sub-11 Milestone". The Gleaner. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "Smiling Fraser just loves to make Jamaica happy Archived 13 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine". (18 August 2009). IAAF. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "Fraser-Pryce, The Greatest Ever Female Sprinter – Michael Johnson". The Gleaner. 1 October 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Greatest Female Sprinter Of All Time?". Olympic Channel. 27 October 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Lowe, Andre (29 September 2019). "MOMMY ROCKET - Fraser-Pryce powers to unmatched fourth World title, dedicates victory to mothers". The Gleaner. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Landell, Steve (24 August 2019). "Fab five: multiple medallists at the World Championships". World Athletics. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Weir, Stewart (12 July 2016). "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce's journey to the top". Athletics Weekly. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Chadband, Ian (29 October 2009). "Shelly-Ann Fraser's rise from poverty to one of the world's best sprinters is remarkable". The Telegraph. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- Urken, Ross Kenneth (1 May 2016). "A Jamaican will go for a third gold medal in Rio — and it's not who you think". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Singhania, Devansh (12 July 2016). "Rio Olympics 2016: Shelly Ann Fraser-Pryce's story of struggle and dominance". Sportskeeda. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Turnbull, Simon (29 March 2013). "Jamaica's Pocket Rocket Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce insists she's not stuck in shadow of Lightning Bolt". The Independent. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "A Need For Speed: Inside Jamaica's Sprint Factory". NPR. 4 May 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Kassel, Anna (9 May 2010). "Olympic champion Shelly-Ann Fraser makes fast work of fame game". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Mulvenney, Nick (17 August 2008). "Fraser leads Jamaican 100m sweep". Reuters. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Landells, Steve (17 August 2009). "Event Report - Women's 100m - Final" Archived 21 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. IAAF. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- "Stunning Jeter run upstages Bolt". BBC Sports. BBC. 13 September 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Olympic champion Shelly-Ann Fraser fails drugs test". BBC Sports. BBC. 9 July 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Scott, Matt; Kessel, Anna (10 July 2020). "Wada defends Jamaica's anti-doping record after Shelly-Ann Fraser test". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Mann, Leon (2 May 2011). "Fraser bids to bounce back". BBC Sports. BBC. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Fraser-Pryce wins gold in women's 100m". Eurosport. 4 August 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Martin, David (23 August 2011). "Women's 100m - PREVIEW". IAAF. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012.

- "Shelly fit again". Radio Jamaica News. 19 July 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "100 metres 2011". IAAF. 8 August 2011. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011.

- Lowe, Andre (2 August 2016). "'Hard To Beat' - Underdog Status Good For Fraser-Pryce, Says Francis". The Gleaner. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Martin, David (29 August 2011). "Women's 100m - Final - Jeter finally strikes gold". IAAF. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Lowe, Andre (29 September 2019). "WONDER WOMEN - Fraser-Pryce, Thompson in race for gold". The Gleander. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Couvée, Koos (12 August 2012). "USA vs Jamaica: who rules the sprint events?". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Zhen, Liu; Master, Farah (22 May 2010). "Shelly-Ann Fraser enjoying the rivalry between Jamaica and U.S". Reuters. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Willes, Ed (31 July 2012). "U.S.A. vs. Jamaica: Track's great rivalry". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "IAAF World Championships – Berlin 2009 – 100 Metres Men Final". Berlin.iaaf.org. 16 August 2009. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- Hart, Simon (20 August 2009). World Athletics: Usain Bolt breaks 200 metres world record in 19.19 seconds Archived 21 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Telegraph. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- Patejdl, Ana (23 July 2012). "Olympic Track 2012: Breaking Down Team USA's Rivalry with Jamaican Sprinters". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Mulvenney, Nick; Maidment, Neil (1 August 2012). Jimenez, Tony (ed.). "Women's track event-by-event analysis". Reuters. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Shannon, Red (1 July 2012). "Olympic Track Trials 2012: Shelly Ann Fraser-Pryce Wins 200m at Jamaica Trials". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Epstein, David (3 August 2012). "Women's 100-meter preview". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Presse, Agence-France (5 August 2012). "London 2012 Athletics: Fraser-Pryce retains women's 100m title". NDTV. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Martin, David (4 August 2012). "London 2012 - Event Report - Women's 100m Final". World Athletics. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Belson, Ken; Pilon, Mary (4 August 2012). "Round One in Sprints to Jamaica; Briton Takes 10,000". New York Times. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Butcher, Pat (5 August 2012). "Fraser-Pryce joins Tyus and Devers in exclusive club". World Athletics. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Bull, Andy (9 August 2012). "Allyson Felix takes 200m gold but Jeter grilling leaves sour taste". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Borden, Sam (10 August 2012). "Clean Passes and a Sparkling Finish". New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Olympics: Jamaica". Sports-reference.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Care, Tony (9 August 2012). "Usain Bolt captures 200m gold medal in Jamaican sweep". CBC Sports. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Ramsak, Bob (11 August 2012). "Jamaica crush 4x100m Relay World record - 36.84 in London!". World Athletics. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Rowbottom, Mike (3 January 2013). "2012 Samsung Diamond League Review – Part 2". World Athletics. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Minshull, Phil (17 November 2012). "A look back at Usain Bolt's and Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce's year on the track". World Athletics. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Phillips, Mitch (16 August 2013). "Brain training turns Fraser-Pryce into double champion". Reuters. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Mulkeen, Jon (12 August 2013). "Report: Women's 100m final – Moscow 2013". World Athletics. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "World Championship 100 m Women's Stats and Figure". IAAF Beijing 2015. 24 August 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Jamaica's Fraser-Pryce wins 100 metres". Sportsnet. 12 August 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Minshull, Phil (18 August 2013). "Report: Women's 4x100m Relay final – Moscow 2013". World Athletics. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Lowe, Andre (6 April 2014). "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce - Leaving Her Mark On And Off The Track". The Gleaner. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Mills, Steven (10 March 2014). "World Indoor Championships – a statistical round-up". Athletics Weekly. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Fraser-Pryce opts not to defend world 200m title in Beijing". The Observer. 3 July 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "'It's A Man's World' - Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce Looking To Add 'Wow' To Women's 100m". The Gleaner. 3 July 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Lowe, Andre (24 August 2015). "Legacy Secured: Fraser-Pryce, Legend". The Observer. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Morley, Gary (24 August 2015). "World Athletics Championships 2015: Fraser-Pryce matches Bolt". CNN. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Johnson, Len (29 August 2015). "Report: women's 4x100m final – IAAF World Championships, Beijing 2015". World Athletics. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Sampaolo, Diego (6 September 2015). "Fraser-Pryce breaks Ottey's meeting record in Padua". World Athletics. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Sully, Kevin (29 May 2016). "Eugene: Fraser-Pryce faces crucial injury test ahead of a potentially historic year". Diamond League. IAAF. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Dutch, Taylor (3 August 2016). "Olympic Preview: Women's Sprints". Flotrack. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Jackson, Jameika (18 July 2016). "Fraser-Pryce for an easy win in Padova". Trackalerts.com. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Pells, Eddie (13 August 2016). "Elaine Thompson Dethrones Fraser-Pryce for 100m Gold, Fastest Woman Title". NBC Sports. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Womens 100m: What a Final This Could Be, Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce Goes for History vs Five Others with a Shot for Gold". Let's Run. 10 August 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Olympics-Jamaican duo set pace in women's 100m semis". Eurosport. 13 August 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Mulvenney, Nick (14 August 2016). "Fraser-Pryce rates Rio bronze 'greatest medal'". Reuters. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- McGowan, Tom (14 August 2016). "Elaine Thompson: Jamaican wins women's 100m gold at Rio 2016 Olympics". CNN. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Graham, Bryan Armen (14 August 2016). "Elaine Thompson surges clear to capture women's 100m gold for Jamaica". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Graham, Raymond (25 August 2016). "Why did Shelly leave". The Gleaner. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Makyn, Ricardo (19 August 2016). "Shelly Shocker! - Top Sprinter To Leave MVP Track Club". The Gleaner. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Reid, Paul (29 November 2016). "Fraser-Pryce returns to MVP". The Observer. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Lowe, Andre (22 July 2018). "'I Am Excited!' - Fraser-Pryce Already Looking Forward To 2019 World Champs After Sub-11 Run". The Gleaner. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Campbell, Morgan (11 August 2018). "Jamaica's Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce falters in NACAC 100-metre final". The Star. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Crumley, Euan (29 September 2019). "Asher-Smith makes history as Fraser-Pryce returns to sprinting summit". Athletics Weekly. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Elaine Thompson, Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce sizzle at Jamaican Championships". NBC Sports. 22 June 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Watta, Evelyn; Knowles, Edwards (19 July 2019). "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce faces big test from Britain's Dina Asher-Smith at 2019 London Anniversary Games". Olympic Channel. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Cherry, Gene (9 August 2019). Ferris, Ken; Mulvenney, Nick (eds.). "Jamaica's Fraser-Pryce smashes 40-year-old Pan Am Games record". Reuters. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Keating, Steve (28 September 2019). "Athletics: Yellow hair and hot time have Fraser-Pryce in spotlight". Reuters. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce". Diamond League. IAAF. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Keating, Steve (29 September 2019). "New face of sport might just be a woman: Fraser-Pryce". Reuters. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Church, Ben (1 October 2019). "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce crowned fastest woman in the world". CNN. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Lowe, Andre (1 October 2019). "I will double in 2020 – Fraser-Pryce". The Star (Jamaica). Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Saraswat, Akshay (15 February 2020). "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce puts world on notice ahead of Olympics; wins Indoor 60m race in Glasgow". Sportskeeda. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Campbell, Alastair (27 November 2019). "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce exclusive interview... on feminism, religion and why Tokyo will be her last Olympics". The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Lowe, Andre (8 May 2017). "I Want To Be The Greatest Mother - Fraser-Pryce". The Gleaner. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Mains, Susan P.; Cupples, Julie; Lukinbeal, Chris, eds. (2015). Mediated Geographies and Geographies of Media. Springer Netherlands. p. 339. ISBN 978-94-017-9969-0.

- "Knocking at the Door". Nike News. 21 June 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Hickling, Allison (23 February 2010). "Olympic Champion Shelly-Ann Fraser appointed as UNICEF Jamaica Goodwill Ambassador". unicef.org. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Redpath, Laura (24 February 2010). "Fraser Named Goodwill Ambassador For Peace". The Gleaner. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Gridley, Latoya (31 December 2013). "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce Launches Chic Hair Ja". The Gleaner. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "The Decade's Top 10 Women By Event". Track & Field News. 1 January 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Ingle, Sean (29 September 2019). "Dina Asher-Smith claims world championship 100m silver". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Church, Ben (30 September 2019). "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce crowned the fastest woman in the world ... not that many fans saw it". CNN. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Myers, Sanjay (24 August 2015). "Shelly-Ann simply the best says track and field analyst". The Observer. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Casert, Raf (12 August 2013). "A pink blur: Jamaica's Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce wins 100 meters; David Oliver takes 110 hurdles". Star Tribune. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Sutton, Nicola (22 September 2020). "'World Athletics Championships 2019: Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce on motherhood, hair and medals". BBC Sports. BBC. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Welcoming home our Olympians". The Gleaner. 5 October 2008. Archived from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- Cross, Jason (14 October 2018). "Fraser-Pryce Immortalised! - Pocket Rocket Honoured With Statue". The Gleaner. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Nayyar, Namita (1 October 2019). "Exclusive Interview: Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce bags her fourth 100 m world title, Catch her on Women Fitness". Women Fitness. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Lowe, Andre (16 January 2016). "Bolt, Shelly sprint away with RJR awards ... again: The Best!". The Gleaner. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "SPORTSWOMAN OF THE YEAR 2020: SHELLY-ANN FRASER-PRYCE". Laureus.com. Laureus World Sports Awards Ltd. 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Reich, Josh (16 November 2013). "Bolt and Fraser-Pryce win 2013 World Athlete awards". Reuters. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "New Spike Prepares Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce for Historical Race". Nike News. 28 June 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Graubner, Rolf; Nixdorf, Eberhard (2011). "Biomechanical Analysis of the Sprint and Hurdles Events at the 2009 IAAF World Championships in Athletics" (PDF). meathathletics.ie. Translated by Schiffer, Jürgen. New Studies in Athletics. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Chang, Alvin (9 August 2016). "Want to win Olympic gold? Here's how tall you should be for archery, swimming, and more". Vox. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Shearman, Hayden (13 August 2013). "Sprinting Cadence and Power". A Runner's Guide. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce: Track and Field Statistics". brinkster.net. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "100 Metres Women: 2008". World Athletics. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "200 Metres Women: 2008". World Athletics. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "200 Metres Women: 2011". World Athletics. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "200 Metres Women: 2012". World Athletics. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "100 Metres Women: 2014". World Athletics. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "200 Metres Women: 2014". World Athletics. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "100 Metres Women: 2018". World Athletics. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce. |

- Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce at World Athletics

- Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce at Olympics at Sports-Reference.com (archived)

Videos

- Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce wins the 2009 World Championships women's 100 meters final in 10.73 seconds via Universal Sports on YouTube

- Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce wins the 2012 Olympic women's 100 meters final in 10.75 seconds via Olympic Channel on YouTube

- Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce wins the 2013 World Championships women's 100 meters final in 10.71 seconds via World Athletics on YouTube

- Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce wins the 2013 World Championships women's 200 meters final in 22.17 seconds via Universal Sports on YouTube

- Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce wins the 2015 World Championships women's 100 meters final in 10.76 seconds via World Athletics on YouTube

- Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce wins the 2019 World Championships women's 100 meters final in 10.71 seconds via World Athletics on YouTube

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by |

IAAF World Athlete of the Year 2013 |

Succeeded by |

| Olympic Games | ||

| Preceded by Usain Bolt |

Flagbearer for Rio de Janeiro 2016 |

Succeeded by Incumbent |