100 metres

The 100 metres, or 100-metre dash, is a sprint race in track and field competitions. The shortest common outdoor running distance, it is one of the most popular and prestigious events in the sport of athletics. It has been contested at the Summer Olympics since 1896 for men and since 1928 for women. The World Championships 100 metres has been contested since 1983.

| Athletics 100 metres | |

|---|---|

Start of the men's 100 metres final at the 2012 Olympic Games. | |

| World records | |

| Men | |

| Women | |

| Olympic records | |

| Men | |

| Women | |

| Championship records | |

| Men | |

| Women | |

The reigning 100 m Olympic or world champion is often named "the fastest man or woman in the world". Christian Coleman and Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce are the reigning world champions; Usain Bolt and Elaine Thompson are the men's and women's Olympic champions.

On an outdoor 400 metres running track, the 100 m is run on the home straight, with the start usually being set on an extension to make it a straight-line race. There are three instructions given to the runners immediately before and at the beginning of the race: ready, set, and the firing of the starter's pistol. The runners move to the starting blocks when they hear the 'ready' instruction. The following instruction, to adopt the 'set' position, allows them to adopt a more efficient starting posture and isometrically preload their muscles: this will help them to start faster. A race-official then fires the starter's pistol to signal the race beginning and the sprinters stride forwards from the blocks. Sprinters typically reach top speed after somewhere between 50 and 60 m. Their speed then slows towards the finish line.

The 10-second barrier has historically been a barometer of fast men's performances, while the best female sprinters take eleven seconds or less to complete the race. The current men's world record is 9.58 seconds, set by Jamaica's Usain Bolt in 2009, while the women's world record of 10.49 seconds set by American Florence Griffith-Joyner in 1988 remains unbroken.[lower-alpha 1]

The 100 m (109.361 yards) emerged from the metrication of the 100 yards (91.44 m), a now defunct distance originally contested in English-speaking countries. The event is largely held outdoors as few indoor facilities have a 100 m straight.

US athletes have won the men's Olympic 100 metres title more times than any other country, 16 out of the 28 times that it has been run. US women have also dominated the event winning 9 out of 21 times.

Race dynamics

Start

At the start, some athletes play psychological games such as trying to be last to the starting blocks.[3][4][5]

At high level meets, the time between the gun and first kick against the starting block is measured electronically, via sensors built in the gun and the blocks. A reaction time less than 0.1 s is considered a false start. The 0.2-second interval accounts for the sum of the time it takes for the sound of the starter's pistol to reach the runners' ears, and the time they take to react to it.

For many years a sprinter was disqualified if responsible for two false starts individually. However, this rule allowed some major races to be restarted so many times that the sprinters started to lose focus. The next iteration of the rule, introduced in February 2003, meant that one false start was allowed among the field, but anyone responsible for a subsequent false start was disqualified.

This rule led to some sprinters deliberately false-starting to gain a psychological advantage: an individual with a slower reaction time might false-start, forcing the faster starters to wait and be sure of hearing the gun for the subsequent start, thereby losing some of their advantage. To avoid such abuse and to improve spectator enjoyment, the IAAF implemented a further change in the 2010 season – a false starting athlete now receives immediate disqualification.[6] This proposal was met with objections when first raised in 2005, on the grounds that it would not leave any room for innocent mistakes. Justin Gatlin commented, "Just a flinch or a leg cramp could cost you a year's worth of work."[7] The rule had a dramatic impact at the 2011 World Championships, when current world record holder Usain Bolt was disqualified.[8][9]

Mid-race

Runners normally reach their top speed just past the halfway point of the race and they progressively decelerate in the later stages of the race. Maintaining that top speed for as long as possible is a primary focus of training for the 100 m.[10] Pacing and running tactics do not play a significant role in the 100 m, as success in the event depends more on pure athletic qualities and technique.

Finish

The winner, by IAAF Competition Rules, is determined by the first athlete with his or her torso (not including limbs, head, or neck) over the nearer edge of the finish line.[11] There is therefore no requirement for the entire body to cross the finish line. When the placing of the athletes is not obvious, a photo finish is used to distinguish which runner was first to cross the line.

Climatic conditions

Climatic conditions, in particular air resistance, can affect performances in the 100 m. A strong head wind is very detrimental to performance, while a tail wind can improve performances significantly. For this reason, a maximum tail wind of 2.0 m/s is allowed for a 100 m performance to be considered eligible for records, or "wind legal".

Furthermore, sprint athletes perform a better run at high altitudes because of the thinner air, which provides less air resistance. In theory, the thinner air would also make breathing slightly more difficult (due to the partial pressure of oxygen being lower), but this difference is negligible for sprint distances where all the oxygen needed for the short dash is already in the muscles and bloodstream when the race starts. While there are no limitations on altitude, performances made at altitudes greater than 1000 m above sea level are marked with an "A".[12]

10-second barrier

The 10-second mark had been widely been considered a barrier for the 100 metres. The first man to break the 10 second barrier was Jim Hines at the 1968 Summer Olympics. Since then, numerous sprinters have run faster than 10 seconds.

Ethnicity

Only male sprinters have beaten the 100 m 10-second barrier, majority of them being of West African descent in particular those descendant from the Atlantic Slave trade. Namibian (formerly South-West Africa) Frankie Fredericks became the first man of non-West African heritage to achieve the feat in 1991 and in 2003 Australia's Patrick Johnson (an Indigenous Australian with Irish heritage) became the first sub-10-second runner without an African background.[13][14][15][16]

In 2010, French sprinter Christophe Lemaitre became the first Caucasian to break the 10-second barrier,[16] In 2017, Azerbaijani-born naturalized Turkish Ramil Guliyev followed[17] and in 2018, Filippo Tortu became the first Italian to run under 10s. In the Prefontaine Classic 2015 Diamond League meet at Eugene, Su Bingtian of China ran a time of 9.99 seconds, becoming the first East Asian athlete to officially break the 10-second barrier. On 22 June 2018, Su improved his time in Madrid with a time of 9.91.[18] On 9 September 2017, Yoshihide Kiryū became the first man from Japan to break the 10-second barrier in the 100 metres, running a 9.98 (+1.8) at an intercollegiate meet in Fukui.

Record performances

Major 100 m races, such as at the Olympic Games, attract much attention, particularly when the world record is thought to be within reach.

The men's world record has been improved upon twelve times since electronic timing became mandatory in 1977.[19] The current men's world record of 9.58 s is held by Usain Bolt of Jamaica, set at the 2009 World Athletics Championships final in Berlin, Germany on 16 August 2009, breaking his own previous world record by 0.11 s.[20] The current women's world record of 10.49 s was set by Florence Griffith-Joyner of the US, at the 1988 United States Olympic Trials in Indianapolis, Indiana, on 16 July 1988[21] breaking Evelyn Ashford's four-year-old world record by .27 seconds. The extraordinary nature of this result and those of several other sprinters in this race raised the possibility of a technical malfunction with the wind gauge which read at 0.0 m/s- a reading which was at complete odds to the windy conditions on the day with high wind speeds being recorded in all other sprints before and after this race as well as the parallel long jump runway at the time of the Griffith-Joyner performance. All scientific studies commissioned by the IAAF and independent organisations since have confirmed there was certainly an illegal tailwind of between 5 m/s – 7 m/s at the time. This should have annulled the legality of this result, although the IAAF has chosen not to take this course of action. The legitimate next best wind legal performance would therefore be Griffith-Joyner's 10.61s performance in the final the next day.[22]

Some records have been marred by prohibited drug use – in particular, the scandal at the 1988 Summer Olympics when the winner, Canadian Ben Johnson was stripped of his medal and world record.

Jim Hines, Ronnie Ray Smith and Charles Greene were the first to break the 10-second barrier in the 100 m, all on 20 June 1968, the Night of Speed. Hines also recorded the first legal electronically timed sub-10 second 100 m in winning the 100 metres at the 1968 Olympics. Bob Hayes ran a wind-assisted 9.91 seconds at the 1964 Olympics.

Continental records

Updated 29 November 2018.[23]

| Area | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (s) | Wind (m/s) | Athlete | Nation | Time (s) | Wind (m/s) | Athlete | Nation | |

| Africa (records) | 9.85 | +1.7 | Olusoji Fasuba | 10.78 | +1.6 | Murielle Ahouré | ||

| Asia (records) | 9.91 | +1.8 | Femi Ogunode | 10.79 | 0.0 | Li Xuemei | ||

| +0.6 | ||||||||

| +0.2 | Su Bingtian | |||||||

| +0.8 | ||||||||

| Europe (records) | 9.86 | +0.6 | Francis Obikwelu | 10.73 | +2.0 | Christine Arron | ||

| +1.3 | Jimmy Vicaut | |||||||

| +1.8 | ||||||||

| North, Central America and Caribbean (records) | 9.58 WR | +0.9 | Usain Bolt | 10.49 WR | 0.0 | Florence Griffith-Joyner | ||

| Oceania (records) | 9.93 | +1.8 | Patrick Johnson | 11.11 | +1.9 | Melissa Breen | ||

| South America (records) | 10.00[A] | +1.6 | Robson da Silva | 10.91 | −0.2 | Rosângela Santos | ||

Notes

- A Represents a time set at a high altitude.[24]

- WR World record

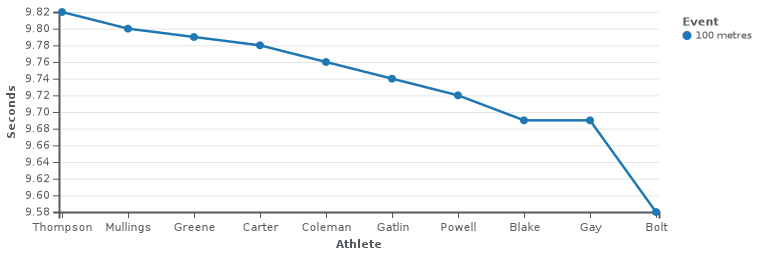

All-time top 25 men

| Rank | Time | Wind (m/s) | Athlete | Country | Date | Place | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.58 | +0.9 | Usain Bolt | 16 August 2009 | Berlin | [27] | |

| 2 | 9.69 | +2.0 | Tyson Gay | 20 September 2009 | Shanghai | [28] | |

| −0.1 | Yohan Blake | 23 August 2012 | Lausanne | [29] | |||

| 4 | 9.72 | +0.2 | Asafa Powell | 2 September 2008 | Lausanne | [30] | |

| 5 | 9.74 | +0.9 | Justin Gatlin | 15 May 2015 | Doha | [31] | |

| 6 | 9.76 | +0.6 | Christian Coleman | 28 September 2019 | Doha | [32] | |

| 7 | 9.78 | +0.9 | Nesta Carter | 29 August 2010 | Rieti | [33] | |

| 8 | 9.79 | +0.1 | Maurice Greene | 16 June 1999 | Athens | [34] | |

| 9 | 9.80 | +1.3 | Steve Mullings | 4 June 2011 | Eugene | [35] | |

| 10 | 9.82 | +1.7 | Richard Thompson | 21 June 2014 | Port of Spain | [36] | |

| 11 | 9.84 | +0.7 | Donovan Bailey | 27 July 1996 | Atlanta | ||

| +0.2 | Bruny Surin | 22 August 1999 | Seville | ||||

| +1.3 | Trayvon Bromell | 25 June 2015 | Eugene | ||||

| +1.6 | 3 July 2016 | [37] | |||||

| 14 | 9.85 | +1.2 | Leroy Burrell | 6 July 1994 | Lausanne | [38] | |

| +1.7 | Olusoji Fasuba | 12 May 2006 | Doha | ||||

| +1.3 | Mike Rodgers | 4 June 2011 | Eugene | ||||

| 17 | 9.86 | +1.2 | Carl Lewis | 25 August 1991 | Tokyo | [39] | |

| −0.7 | Frankie Fredericks | 3 July 1996 | Lausanne | ||||

| +1.8 | Ato Boldon | 19 April 1998 | Walnut | ||||

| +0.6 | Francis Obikwelu | 22 August 2004 | Athens | ||||

| +1.4 | Keston Bledman | 23 June 2012 | Port of Spain | ||||

| +1.3 | Jimmy Vicaut | 4 July 2015 | Saint-Denis | [40] | |||

| +0.9 | Noah Lyles | 18 May 2019 | Shanghai | [41] | |||

| +0.8 | Divine Oduduru | 7 June 2019 | Austin | [42] | |||

| 25 | 9.87 | +0.3 | Linford Christie | 15 August 1993 | Stuttgart | ||

| 9.87[A] | −0.2 | Obadele Thompson | 11 September 1998 | Johannesburg | |||

| 9.87 | −0.1 | Ronnie Baker | 22 August 2018 | Chorzów | [43] |

More facts about these male runners

- Usain Bolt also holds the world record for the fastest 100 metres with a running start at 8.70 (41 km/h). This was achieved in a 150 metres race during the BUPA Great City Games in Manchester on 17 May 2009, completed in 14.35 (also a world record).[44] He also ran 9.63 (2012), 9.69 (2008), 9.72 (2008), 9.76 (2008, 2011, 2012), 9.77 (2008, 2013), 9.79 (2009, 2012, 2015), 9.80 (2013), 9.81 (2009, 2016), 9.82 (2010, 2012), 9.83 (2008), 9.84 (2010), 9.85 (2008, 2011, 2013), 9.86 (2009, 2010, 2012, 2016) and 9.87 (2012, 2015).

- Tyson Gay also ran 9.71 (2009), 9.77 (2008, 2009), 9.78 (2010), 9.79 (2010, 2011), 9.84 (2006, 2007, 2010), 9.85 (2007, 2008), 9.86 (2012), and 9.87 (2015).

- Asafa Powell also ran 9.74 (2007), 9.77 (2005, 2006, 2008), 9.78 (2007, 2011), 9.81 (2015), 9.82 (2008, 2009, 2010), 9.83 (2007, 2008, 2010), 9.84 (2005, 2007, 2009, 2015), 9.85 (2005, 2006, 2009, 2012), 9.86 (2006, 2011), and 9.87 (2004, 2008, 2014, 2015).

- Yohan Blake also ran 9.75 (2012), 9.76 (2012), 9.82 (2011), 9.84 (2012), and 9.85 (2012).

- Justin Gatlin ran 9.77 in Doha on 12 May 2006, which was at the time ratified as a world record. However, the record was rescinded in 2007 after he failed a doping test in April 2006. He also ran 9.75 (2015), 9.77 (2014, 2015), 9.78 (2015), 9.79 (2012), 9.80 (2012, 2014, 2015, 2016), 9.82 (2012, 2014), 9.83 (2014, 2016), 9.85 (2004, 2013) 9.86 (2014), and 9.87 (2012, 2014, 2019).

- Tim Montgomery ran 9.78 in Paris on 14 September 2002, which was at the time ratified as a world record.[45] However, the record was rescinded in December 2005 following his indictment in the BALCO scandal on drug use and drug trafficking charges.[46] The time had stood as the world record until Asafa Powell first ran 9.77.[47]

- Ben Johnson ran 9.79 in Seoul on 24 September 1988, but he was disqualified after he tested positive for stanozolol after the race. He subsequently admitted to drug use between 1981 and 1988, and his time of 9.83 at Rome on 30 August 1987 was rescinded.

- Christian Coleman also ran 9.79 (2018), 9.81 (2019), 9.82 (2017), 9.85 (2019), and 9.86 (2019).

- Maurice Greene also ran 9.80 (1999), 9.82 (2001), 9.85 (1999), 9.86 (1997, 2000), and 9.87 (1999, 2000, 2004).

- Trayvon Bromell also ran 9.84 (2016).

- Nesta Carter also ran 9.85 (2010), 9.86 (2010), and 9.87 (2013).

- Richard Thompson also ran 9.85 (2011).

- Ato Boldon also ran 9.86 (1998, 1999) and 9.87 (1997).

- Keston Bledman also ran 9.86 (2015).

- Mike Rodgers also ran 9.86 (2015).

- Jimmy Vicaut also ran 9.86 (2016).

- Frankie Fredericks also ran 9.87 (1996).

- Dwain Chambers ran 9.87 in Paris on 14 September 2002, which at the time equaled the European record. He tested positive for tetrahydrogestrinone in October 2003, and was given a two-year suspension in February 2004. Originally he claimed innocence, but after his suspension ended in November 2005 he admitted to doping during the 2002 and 2003 seasons. His record was subsequently rescinded in June 2006.[48]

- Steve Mullings is serving a lifetime ban for doping.[49]

Assisted marks

Any performance with a following wind of more than 2.0 metres per second is not counted for record purposes. Below is a list of the fastest wind-assisted times (9.80 or better). Only times that are superior to legal bests are shown.

- Justin Gatlin ran 9.45 (+20 m/s) in 2011 on the Japanese TV show Kasupe! assisted by wind machines blowing at speeds over 25 metres per second.[50]

- Tyson Gay (USA) ran 9.68 (+4.1 m/s) during the U.S. Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon on 29 June 2008.[51]

- Obadele Thompson (BAR) ran 9.69 (+5.7 m/s) in El Paso, Texas on 13 April 1996, which stood as the fastest ever 100 metres time for 12 years.

- Andre De Grasse (CAN) ran 9.69 (+4.8 m/s) during the Diamond League in Stockholm on 18 June 2017[52] and 9.75 (+2.7 m/s) during the NCAA Outdoor Track and Field Championships in Eugene, Oregon on 12 June 2015.

- Richard Thompson (TTO) ran 9.74 (exact wind unknown) in Clermont, Florida on 31 May 2014.

- Darvis Patton (USA) ran 9.75 (+4.3 m/s) in Austin, Texas on 30 March 2013.

- Churandy Martina (AHO) ran 9.76 (+6.1 m/s) in El Paso, Texas on 13 May 2006.

- Trayvon Bromell (USA) ran 9.76 (+3.7 m/s) in Eugene, Oregon on 26 June 2015 and 9.77 (+4.2 m/s) in Lubbock, Texas on 18 May 2014.

- Carl Lewis (USA) ran 9.78 (+5.2 m/s) during the U.S. Olympic Trials in Indianapolis on 16 July 1988 and 9.80 (+4.3 m/s) during the World Championships in Tokyo on 24 August 1991.

- Maurice Greene (USA) ran 9.78 (+3.7 m/s) in Eugene, Oregon on 31 May 2004.

- Ronnie Baker (USA) ran 9.78 (+2.4 m/s) during the Diamond League in Eugene, Oregon on 26 May 2018.

- Andre Cason (USA) ran 9.79 (+5.3 m/s) and (+4.5 m/s) in Eugene, Oregon on 16 June 1993.

- Walter Dix (USA) ran 9.80 (+4.1 m/s) during the U.S. Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon on 29 June 2008.

- Mike Rodgers (USA) ran 9.80 (+2.7 m/s) in Eugene, Oregon on 31 May 2014 and 9.80 (+2.4 m/s) in Sacramento, California on 27 June 2014.

All-time top 25 women

| Rank | Time | Wind (m/s) | Athlete | Nation | Date | Location | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.49 | 0.0[lower-alpha 1] | Florence Griffith-Joyner | 16 July 1988 | Indianapolis | ||

| 2 | 10.64 | +1.2 | Carmelita Jeter | 20 September 2009 | Shanghai | ||

| 3 | 10.65 [A] | +1.1 | Marion Jones | 12 September 1998 | Johannesburg | ||

| 4 | 10.70 | +0.6 | Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce | 29 June 2012 | Kingston | ||

| +0.3 | Elaine Thompson | 1 July 2016 | Kingston | [55] | |||

| 6 | 10.73 | +2.0 | Christine Arron | 19 August 1998 | Budapest | ||

| 7 | 10.74 | +1.3 | Merlene Ottey | 7 September 1996 | Milan | ||

| +1.0 | English Gardner | 3 July 2016 | Eugene | [37] | |||

| 9 | 10.75 | +0.4 | Kerron Stewart | 10 July 2009 | Rome | ||

| +1.6 | Sha'Carri Richardson | 8 June 2019 | Austin | [56] | |||

| 11 | 10.76 | +1.7 | Evelyn Ashford | 22 August 1984 | Zürich | ||

| +1.1 | Veronica Campbell-Brown | 31 May 2011 | Ostrava | ||||

| 13 | 10.77 | +0.9 | Irina Privalova | 6 July 1994 | Lausanne | ||

| +0.7 | Ivet Lalova | 19 June 2004 | Plovdiv | ||||

| 15 | 10.78 [A] | +1.0 | Dawn Sowell | 3 June 1989 | Provo | ||

| 10.78 | +1.8 | Torri Edwards | 26 June 2008 | Eugene | |||

| +1.6 | Murielle Ahouré | 11 June 2016 | Montverde | [57] | |||

| +1.0 | Tianna Bartoletta | 3 July 2016 | Eugene | [37] | |||

| +1.0 | Tori Bowie | 3 July 2016 | Eugene | [37] | |||

| 20 | 10.79 | 0.0 | Li Xuemei | 18 October 1997 | Shanghai | ||

| −0.1 | Inger Miller | 22 August 1999 | Seville | ||||

| +1.1 | Blessing Okagbare | 27 July 2013 | London | ||||

| 23 | 10.81 | +1.7 | Marlies Göhr | 8 June 1983 | Berlin | ||

| −0.3 | Dafne Schippers | 24 August 2015 | Beijing | [58] | |||

| 25 | 10.82 | −1.0 | Gail Devers | 1 August 1992 | Barcelona | ||

| +1.5 | 7 July 1993 | Lausanne | |||||

| −0.3 | 16 August 1993 | Stuttgart | |||||

| +0.4 | Gwen Torrence | 3 September 1994 | Paris | ||||

| −0.3 | Zhanna Block | 6 August 2001 | Edmonton | ||||

| −0.7 | Sherone Simpson | 24 June 2006 | Kingston | ||||

| +0.9 | Michelle-Lee Ahye | 24 June 2017 | Port of Spain | [59] |

More facts about these female runners

- Florence Griffith-Joyner's world record has been the subject of a controversy due to strong suspicion of a defective anemometer measuring a tailwind lower than actually present;[60] since 1997 the International Athletics Annual of the Association of Track and Field Statisticians has listed this performance as "probably strongly wind assisted, but recognised as a world record".[61] It can be reasonable to assume a wind reading of about +4.7 m/s for Griffith-Joyner's quarter-final. Her legal 10.61 the following day and 10.62 at the 1988 Olympics would still make her the world record holder.[62]

Below is a list of all other legal times equal or superior to 10.82:

- As well as the 10.61 (1988) and 10.62 (1988) mentioned in the more facts section, Florence Griffith-Joyner also ran 10.70 (1988).

- Carmelita Jeter also ran 10.67 (2009), 10.70 (2011), 10.78 (2011, 2012), 10.81 (2012), and 10.82 (2010).

- Marion Jones also ran 10.70 (1999), 10.71 (1998), 10.72 (1998), 10.75 (1998), 10.76 (1997, 1999), 10.77 (1998), 10.78 (2000), 10.79 (1998), 10.80 (1998, 1999), 10.81 (1997, 1998), and 10.82 (1998).

- Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce also ran 10.71 (2013, 2019), 10.72 (2013), 10.73 (2009, 2019), 10.74 (2015, 2019), 10.75 (2012), 10.76 (2015), 10.77 (2013), 10.78 (2008, 2019), 10.79 (2009, 2015), 10.80 (2019), 10.81 (2015, 2019), and 10.82 (2015).

- Elaine Thompson also ran 10.71 (2016, 2017), 10.72 (2016), 10.73 (2019), and 10.78 (2016, 2017).

- Kerron Stewart also ran 10.75 (2009) and 10.80 (2008).

- Merlene Ottey also ran 10.78 (1990, 1994), 10.79 (1991), 10.80 (1992), and 10.82 (1990, 1993).

- Veronica Campbell-Brown also ran 10.78 (2010), 10.81 (2012), and 10.82 (2012).

- Evelyn Ashford also ran 10.79 (1983) and 10.81 (1988).

- English Gardner also ran 10.79 (2015) and 10.81 (2016).

- Tori Bowie also ran 10.80 (2014, 2016), 10.81 (2015), and 10.82 (2015).

- Blessing Okagbare also ran 10.80 (2015).

- Christine Arron also ran 10.81 (1998).

- Inger Miller also ran 10.81 (1999).

- Murielle Ahouré also ran 10.81 (2015).

- Irina Privalova also ran 10.82 (1992).

- Gail Devers also ran 10.82 (1993).

- Gwen Torrence also ran 10.82 (1996).

Assisted marks

Any performance with a following wind of more than 2.0 metres per second is not counted for record purposes. Below is a list of the fastest wind-assisted times (10.82 or better). Only times that are superior to legal bests are shown.

- Tori Bowie (USA) ran 10.72 (+3.2 m/s) during the USA Outdoor Track and Field Championships in Eugene, Oregon on 26 June 2015 and 10.74 (+3.1 m/s) during the U.S. Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon on 3 July 2016.

- Tawanna Meadows (USA) ran 10.72 (+4.5 m/s) in Lubbock, Texas on 6 May 2017.

- Blessing Okagbare (NGR) ran 10.72 (+2.7 m/s) in Austin, Texas on 31 March 2018 and 10.75 (+2.2 m/s) in Eugene, Oregon on 1 June 2013.

- Marshevet Hooker (USA) ran 10.76 (+3.4 m/s) during the U.S. Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon on 27 June 2008.

- Gail Devers (USA) ran 10.77 (+2.3 m/s) in San Jose, California on 28 May 1994.

- Ekaterini Thanou (GRE) ran 10.77 (+2.3 m/s) in Rethymno on 29 May 1999.

- Gwen Torrence (USA) ran 10.78 (+5.0 m/s) during the U.S. Olympic Trials in Indianapolis on 16 July 1988.

- Muna Lee (USA) ran 10.78 (+3.3 m/s) in Eugene, Oregon on 26 June 2009.

- Marlies Göhr (GDR) ran 10.79 (+3.3 m/s) in Cottbus on 16 July 1980.

- Kelli White (USA) ran 10.79 (+2.3 m/s) in Carson, California on 1 June 2001. This performance was annulled in 2003 after she tested positive for modafinil.

- Pam Marshall (USA) ran 10.80 (+2.9 m/s) in Eugene, Oregon on 20 June 1986.

- Heike Drechsler (GDR) ran 10.80 (+2.8 m/s) in Oslo on 5 July 1986.

- Jenna Prandini (USA) ran 10.81 (+3.6 m/s) during the U.S. Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon on 2 July 2016.

- Silke Gladisch (GDR) ran 10.82 (+2.2 m/s) in Rome on 30 August 1987.

Season's bests

Men

|

Women

|

Top 17 junior (under-20) men

As of 29 March 2020[63]

| Rank | Time | Wind (m/s) | Athlete | Nation | Date | Location | Age | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.97 | +1.8 | Trayvon Bromell | 13 June 2014 | Eugene | 18 years, 338 days | [64] | |

| 2 | 10.00 | +1.6 | Trentavis Friday | 5 July 2014 | Eugene | 19 years, 30 days | ||

| 3 | 10.01 | +0.0 | Darrel Brown | 24 August 2003 | Saint-Denis | 18 years, 317 days | ||

| +1.6 | Jeff Demps | 28 June 2008 | Eugene | 18 years, 172 days | ||||

| +0.9 | Yoshihide Kiryu | 28 April 2013 | Hiroshima | 17 years, 134 days | [65] | |||

| 6 | 10.03 | +0.7 | Marcus Rowland | 31 July 2009 | Port of Spain | 19 years, 142 days | ||

| +1.7 | Lalu Muhammad Zohri | 19 May 2019 | Osaka | 18 years, 322 days | [66] | |||

| 8 | 10.04 | +1.7 | D'Angelo Cherry | 10 June 2009 | Fayetteville | 18 years, 313 days | ||

| +0.2 | Christophe Lemaitre | 24 July 2009 | Novi Sad | 19 years, 43 days | ||||

| +1.9 | Abdullah Abkar Mohammed | 15 April 2016 | Norwalk | 18 years, 319 days | [67] | |||

| 11 | 10.05 | Davidson Ezinwa | 3 January 1990 | Bauchi | 18 years, 42 days | |||

| +0.1 | Adam Gemili | 11 July 2012 | Barcelona | 18 years, 279 days | ||||

| +0.6 | Abdul Hakim Sani Brown | 24 June 2017 | Osaka | 18 years, 110 days | [68] | |||

| −0.6 | 4 August 2017 | London | 18 years, 151 days | [69] | ||||

| 14 | 10.06 | 0.0 | Sunday Emmanuel | 26 April 1997 | Walnut | 18 years, 200 days | ||

| +2.0 | Dwain Chambers | 25 July 1997 | Ljubljana | 19 years, 111 days | ||||

| +1.5 | Walter Dix | 7 May 2005 | New York | 19 years, 116 days | ||||

| +0.8 | Phatutshedzo Maswanganye | 14 March 2020 | Pretoria | 19 years, 42 days | [70] |

Notes

- Trayvon Bromell's junior world record is also the age-18 world record. He also recorded the fastest wind-assisted (+4.2 m/s) time for a junior or age-18 athlete of 9.77 seconds on 18 May 2014 (age 18 years, 312 days).[71]

- Yoshihide Kiryu's time of 10.01 seconds matched the junior world record set by Darrel Brown and Jeff Demps, but was not ratified because of the type of wind gauge used.[72]

- British sprinter Mark Lewis-Francis recorded a time of 9.97 seconds on 4 August 2001 (age 18 years, 334 days), but the wind gauge malfunctioned.[73]

- Nigerian sprinter Davidson Ezinwa recorded a time of 10.05 seconds on 4 January 1990 (age 18 years, 43 days), but with no wind gauge.[74]

Below is a list of all other legal times equal or superior to 10.06:

- Abdul Hakim Sani Brown also ran 10.06 (2017).

Top 20 junior (under-20) women

Updated 5 January 2020[75]

| Rank | Time | Wind (m/s) | Athlete | Nation | Date | Location | Age | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.75 | +1.6 | Sha'Carri Richardson | 8 June 2019 | Austin | 19 years, 75 days | [56] | |

| 2 | 10.88 | +2.0 | Marlies Göhr | 1 July 1977 | Dresden | 19 years, 102 days | ||

| 3 | 10.89 | +1.8 | Katrin Krabbe | 20 July 1988 | Berlin | 18 years, 241 days | ||

| 4 | 10.98 | +2.0 | Candace Hill | 20 June 2015 | Shoreline | 16 years, 129 days | [76] | |

| 5 | 10.99 | +0.9 | Ángela Tenorio | 22 July 2015 | Toronto | 19 years, 176 days | [77] | |

| +1.7 | Twanisha Terry | 21 April 2018 | Torrance | 19 years, 148 days | [78] | |||

| 7 | 11.02 | +1.8 | Tamara Clark | 12 May 2018 | Knoxville | 19 years, 123 days | ||

| +0.8 | Briana Williams | 8 June 2019 | Albuquerque | 17 years, 79 days | ||||

| 9 | 11.03 | +1.7 | Silke Gladisch-Möller | 8 June 1983 | Berlin | 18 years, 353 days | ||

| +0.6 | English Gardner | 14 May 2011 | Tucson | 19 years, 22 days | ||||

| 11 | 11.04 | +1.4 | Angela Williams | 5 June 1999 | Boise | 19 years, 126 days | ||

| +1.6 | Kiara Grant | 8 June 2019 | Austin | 18 years, 243 days | [79] | |||

| 13 | 11.06 | +0.9 | Khalifa St. Fort | 24 June 2017 | Port of Spain | 19 years, 131 days | [80] | |

| 14 | 11.07 | +0.7 | Bianca Knight | 27 June 2008 | Eugene | 19 years, 177 days | ||

| 15 | 11.08 | +2.0 | Brenda Morehead | 21 June 1976 | Eugene | 18 years, 260 days | ||

| 16 | 11.09 | NWI | Angela Williams | 14 April 1984 | Nashville | 18 years, 335 days | ||

| 17 | 11.10 | +0.9 | Kaylin Whitney | 5 July 2014 | Eugene | 16 years, 118 days | ||

| 18 | 11.11 | +0.2 | Shakedia Jones | 2 May 1998 | Westwood | 19 years, 48 days | ||

| +1.1 | Joan Uduak Ekah | 2 July 1999 | Lausanne | 17 years, 224 days | ||||

| 20 | 11.12 | +2.0 | Veronica Campbell-Brown | 18 October 2000 | Santiago | 18 years, 156 days | ||

| +1.2 | Alexandria Anderson | 22 June 2006 | Indianapolis | 19 years, 145 days | ||||

| +1.1 | Aurieyall Scott | 24 June 2011 | Eugene | 19 years, 37 days | ||||

| +0.9 | Ewa Swoboda | 21 July 2016 | Bydgoszcz | 18 years, 361 days |

Notes

- Briana Williams ran 10.94 s at the Jamaican Championships on 21 June 2019, which would have made her the fourth fastest junior female of all-time.[81] However, she tested positive for the banned diuretic hydrochlorothiazide during the competition. She was determined to be not at fault and received no period of ineligibility to compete, but her results from the Jamaican Championships were nullified.[82][83][84]

Below is a list of all other legal times equal or superior to 10.99:

- Sha'Carri Richardson also ran 10.99 (2019).

Top 15 Youth (under-18) boys

Updated 5 January 2020[85]

| Rank | Time | Wind (m/s) | Athlete | Country | Date | Location | Age | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.15 | +2.0 | Anthony Schwartz | 31 March 2017 | Gainesville | 16 years, 207 days | [86] | |

| 2 | 10.19 | +0.5 | Yoshihide Kiryu | 3 November 2012 | Fukuroi | 16 years, 324 days | ||

| 3 | 10.20 | +1.4 | Darryl Haraway | 15 June 2014 | Greensboro | 17 years, 87 days | ||

| +1.5 | Tlotliso Leotlela | 7 September 2015 | Apia | 17 years, 118 days | [87] | |||

| +2.0 | Sachin Dennis | 23 March 2018 | Kingston | 15 years, 233 days | [88] | |||

| 6 | 10.22 | +1.0 | Abdul Hakim Sani Brown | 14 May 2016 | Shanghai | 17 years, 69 days | ||

| 7 | 10.23 | +0.8 | Tamunosiki Atorudibo | 23 March 2002 | Enugu | 17 years, 2 days | ||

| +1.2 | Rynell Parson | 21 June 2007 | Indianapolis | 16 years, 345 days | ||||

| 9 | 10.24 | +0.0 | Darrel Brown | 14 April 2001 | Bridgetown | 16 years, 185 days | ||

| 10 | 10.25 | +1.5 | J-Mee Samuels | 11 July 2004 | Knoxville | 17 years, 52 days | ||

| +1.6 | Jeff Demps | 1 August 2007 | Knoxville | 17 years, 205 days | ||||

| +0.9 | Jhevaughn Matherson | 5 March 2016 | Kingston | 17 years, 7 days | [89] | |||

| 13 | 10.26 | +1.2 | Deworski Odom | 21 July 1994 | Lisbon | 17 years, 101 days | ||

| −0.1 | Sunday Emmanuel | 18 March 1995 | Bauchi | 16 years, 161 days | ||||

| 15 | 10.27 | +0.2 | Henry Thomas | 19 May 1984 | Norwalk | 16 years, 314 days | ||

| +1.6 | Curtis Johnson | 30 June 1990 | Fresno | 16 years, 188 days | ||||

| +1.0 | Ivory Williams | 8 June 2002 | Sacramento | 17 years, 37 days | ||||

| −0.2 | Jazeel Murphy | 23 April 2011 | Montego Bay | 17 years, 55 days | ||||

| +1.9 | Raheem Chambers | 20 April 2014 | Fort-de-France | 16 years, 196 days |

Top 15 Youth (under-18) girls

Updated 5 January 2020[90]

| Rank | Time | Wind (m/s) | Athlete | Nation | Date | Location | Age | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.98 | +2.0 | Candace Hill | 20 June 2015 | Shoreline | 16 years, 129 days | [76] | |

| 2 | 11.02 | +0.8 | Briana Williams | 8 June 2019 | Albuquerque | 17 years, 79 days | ||

| 3 | 11.10 | +0.9 | Kaylin Whitney | 5 July 2014 | Eugene | 16 years, 118 days | [91] | |

| 4 | 11.13 | +2.0 | Chandra Cheeseborough | 21 June 1976 | Eugene | 17 years, 163 days | ||

| +1.6 | Tamari Davis | 9 June 2018 | Montverde | 15 years, 159 days | ||||

| 6 | 11.14 | +1.7 | Marion Jones | 6 June 1992 | Norwalk | 16 years, 238 days | ||

| −0.5 | Angela Williams | 21 June 1997 | Edwardsville | 17 years, 142 days | ||||

| 8 | 11.16 | +1.2 | Gabrielle Mayo | 22 June 2006 | Indianapolis | 17 years, 147 days | ||

| +0.9 | Kevona Davis | 23 March 2018 | Kingston | 16 years, 93 days | ||||

| 10 | 11.17 A | +0.6 | Wendy Vereen | 3 July 1983 | Colorado Springs | 17 years, 70 days | ||

| 11 | 11.19 | 0.0 | Khalifa St. Fort | 16 July 2015 | Cali | 17 years, 153 days | ||

| 12 | 11.20 A | +1.2 | Raelene Boyle | 15 October 1968 | Mexico City | 17 years, 144 days | ||

| 13 | 11.24 | −1.0 | Ewa Swoboda | 4 June 2015 | Sankt Pölten | 17 years, 313 days | ||

| 14 | 11.24 | +1.2 | Jeneba Tarmoh | 22 June 2006 | Indianapolis | 16 years, 268 days | ||

| +0.8 | Jodie Williams | 31 May 2010 | Bedford | 16 years, 245 days |

Notes

- Briana Williams ran 10.94 s at the Jamaican Championships on 21 June 2019, which would have been a world under-18 best time.[81] However, she tested positive for the banned diuretic hydrochlorothiazide during the competition. She was determined to be not at fault and received no period of ineligibility to compete, but her results from the Jamaican Championships were nullified.[82][83][84]

Para world records men

Updated 6 October 2019[92]

| Class | Time | Wind (m/s) | Athlete | Nationality | Date | Place | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T11 | 10.92 | +1.8 | David Brown | 18 April 2014 | Walnut | ||

| T12 | 10.45 | +1.8 | Salum Ageze Kashafali | 13 June 2019 | Oslo | [93] | |

| T13 | 10.46 | +0.6 | Jason Smyth | 1 September 2012 | London | ||

| T32 | 23.25 | 0.0 | Martin McDonagh | 13 August 1999 | Nottingham | ||

| T33 | 16.46 | +1.3 | Ahmad Almutairi | 12 May 2015 | Doha | ||

| +1.0 | 3 June 2017 | Nottwil | |||||

| T34 | 14.46 | +0.6 | Walid Ktila | 1 June 2019 | Arbon | ||

| T35 | 12.22 | +0.7 | Ihor Tsvietov | 9 September 2016 | Rio de Janeiro | [94] | |

| T36 | 11.87 | −0.5 | Mohamad Ridzuan Mohamad Puzi | 9 October 2018 | Jakarta | [95] | |

| T37 | 11.42 | +0.2 | Charl du Toit | 10 September 2016 | Rio de Janeiro | [96] | |

| T38 | 10.74 | −0.3 | Hu Jianwen | 13 September 2016 | Rio de Janeiro | [97] | |

| T42 | 12.56 | −0.2 | Record mark (previous record removed) | 1 January 2019 | Bonn | ||

| T43 | vacant | ||||||

| T44 | 11.12 | +0.1 | Mpumelelo Mhlongo | 29 August 2019 | Paris | ||

| T45 | 10.94 | +0.2 | Yohansson Nascimento | 6 September 2012 | London | ||

| T46/47 | 10.50 | +0.5 | Petrucio Ferreira dos Santos | 15 June 2018 | Paris | ||

| T51 | 19.89 | +1.3 | Peter Genyn | 31 May 2018 | Nottwil | ||

| T52 | 16.41 | +0.2 | Raymond Martin | 30 May 2019 | Arbon | ||

| T53 | 14.10 | +0.7 | Brent Lakatos | 27 May 2017 | Arbon | ||

| T54 | 13.63 | +1.0 | Leo-Pekka Tähti | 1 September 2012 | London | ||

| T61 | 12.77 | −0.1 | Ntando Mahlangu | 20 March 2019 | Stellenbosch | ||

| T62 | 10.66 | +1.3 | Johannes Floors | 21 June 2019 | Leverkusen | ||

| T63 | 11.95 | +1.9 | Vinicius Goncalves Rodrigues | 25 April 2019 | São Paulo | ||

| T64 | 10.61 | +1.4 | Richard Browne | 29 October 2015 | Doha |

Para world records women

Updated 4 September 2019[98]

| Classification | Time | Wind (m/s) | Athlete | Nationality | Date | Place | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T11 | 11.91 | +0.7 | Libby Clegg | 9 September 2016 | Rio de Janeiro | [99] | |

| T12 | 11.40 | +0.2 | Omara Durand | 9 September 2016 | Rio de Janeiro | [100] | |

| T13 | 11.79 | +0.5 | Leilia Adzhametova | 11 September 2016 | Rio de Janeiro | [101] | |

| T32 | 37.67 | 0.0 | Lindsay Wright | 25 July 1997 | Nottingham | ||

| T33 | 19.89 | +0.3 | Shelby Watson | 26 May 2016 | Nottwil | ||

| T34 | 16.80 | +0.5 | Kare Adenegan | 21 July 2018 | London | ||

| T35 | 13.43 | +0.9 | Isis Holt | 19 July 2017 | London | ||

| T36 | 13.68 | +1.5 | Shi Yiting | 20 July 2017 | London | ||

| T37 | 13.10 | +1.3 | Mandy Francois-Elie | 24 May 2019 | Nottwil | ||

| T38 | 12.43 | +1.3 | Sophie Hahn | 19 May 2019 | Loughborough | ||

| T42 | 14.61 | −0.2 | Martina Caironi | 30 October 2015 | Doha | [102] | |

| T43 | 12.80 | +1.0 | Marlou van Rhijn | 29 October 2015 | Doha | [103] | |

| T44 | 12.72 | +0.5 | Irmgard Bensusan | 24 May 2019 | Nottwil | [104] | |

| 12.72 | +1.8 | Irmgard Bensusan | 21 June 2019 | Leverkusen | |||

| T45 | 14.00 | 0.0 | Giselle Cole | 2 June 1980 | Arnhem | ||

| T46/47 | 11.95 | −0.2 | Yunidis Castillo | 4 September 2012 | London | ||

| T51 | 24.69 | −0.8 | Cassie Mitchell | 2 July 2016 | Charlotte | ||

| T52 | 18.67 | +1.7 | Michelle Stilwell | 14 July 2012 | Windsor | ||

| T53 | 16.19 | +1.0 | Huang Lisha | 8 September 2016 | Rio de Janeiro | [105] | |

| T54 | 15.35 | +1.9 | Tatyana McFadden | 5 June 2016 | Indianapolis | ||

| T61 | 21.58 | −0.2 | Erina Yuguchi | 11 May 2019 | Beijing | ||

| T62 | 13.63 | +1.0 | Fleur Jong | 15 June 2019 | Nijmegen | ||

| T63 | 14.61 | −0.2 | Martina Caironi | 30 October 2015 | Doha | ||

| T64 | 12.66 | +0.5 | Marlene van Gansewinkel | 24 May 2019 | Nottwil | [104] |

Olympic medallists

Men

Women

World Championship medallists

Men

Women

See also

Notes

- It is widely believed that the anemometer was faulty for the race in which Florence Griffith Joyner set the official world record for the women's 100 m of 10.49 s.[1] A 1995 report commissioned by the IAAF estimated the true wind speed was between +5.0 m/s and +7.0 m/s, rather than the 0.0 recorded.[1] If this time, recorded in the quarter-final of the 1988 U.S. Olympic trials, were excluded, the world record would be 10.61 s, recorded the next day at the same venue by the same athlete in the final.[1]

[2]

References

- Linthorne, Nicholas P. (June 1995). "The 100-m World Record by Florence Griffith-Joyner at the 1988 U.S. Olympic Trials" (PDF). Brunel University. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- "Women's outdoor 100m". All-time top lists. IAAF. 17 September 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- Bob Harris; Ramela Mills; Shanon Parker-Bennett (22 June 2004). BTEC First Sport. Heinemann. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-435-45460-9.

- The Day – 23 January 1983

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "IAAF keeps one false-start rule". BBC. 3 August 2005. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- "Gatlin queries false start change". BBC News. 6 May 2005. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- Christopher Clarey (28 August 2011). "Who Can Beat Bolt in the 100? Himself". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- "The disqualification of Usain Bolt". IAAF. 28 August 2011. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- "Usain Bolt 100m 10 meter Splits and Speed Endurance". Speedendurance.com. 22 August 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- Sandre-Tom. "IAAF Competition Rules 2009, Rule 164" (PDF). IAAF. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- 100 metres IAAF

- Will Swanton and David Sygall, (15 July 2007). Holy Grails. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 June 2009. Archived 2009-06-20.

- The above source fails to mention that Namibian Frankie Fredericks was the first runner of non-West African descent to break the barrier.

- Athlete Profiles – Patrick Johnson. Athletics Australia. Retrieved 19 June 2009. Archived 20 June 2009.

- Jad, Adrian (July 2011). "Christophe Lemaitre 100m 9.92s +2.0 (Video) – Officially the Fastest White Man in History". adriansprints.com. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- https://www.iaaf.org/athletes/turkey/ramil-guliyev-226874

- http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-06/23/c_137274534.htm

- "Progression of 100 meters world record". ESPN. Associated Press. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "100 Metres Results" (PDF). IAAF. 16 August 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- 100 Metres All Time. IAAF (9 March 2009). Retrieved 6 May 2009. Archived 8 May 2009.

- Linthorne,N.(PHD)(1995)The 100m World Record by Florence Griffith Joyner at the 1988 U.S Olympic Trials. Report for the International Amateur Athletic Federation Department of Physics, University of Western Australia

- 100 metres records. IAAF (6 September 2011). Retrieved 9 June 2011. Archived 6 September 2011.

- 60 Metres Records. IAAF (4 April 2009). Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- "RECORDS & LISTS – ALL TIME TOP LISTS – SENIOR OUTDOOR 100 METRES MEN". IAAF. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- "All-time men's best 100m". alltime-athletics.com. 25 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Layden, Tim (31 August 2009). "Bolt Strikes Twice". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "Tyson Gay equals Usain Bolt's old world record with second fastest 100m". The Guardian. 20 September 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Campigotto, Jesse (23 August 2012). "Yohan Blake becomes 3rd man to run 9.69". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Ledsom, Mark (2 September 2008). "Powell equals second fastest 100 meters time". Reuters. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "Justin Gatlin runs fastest 100 meters in world this year". ESPN. 15 May 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "100m Results" (PDF). IAAF. 28 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Nesta Carter ties for fastest 100 of year". The Seattle Times. 29 August 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Litsky, Frank (17 June 1999). "Greene Breaks World Record in the 100 Meters". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Cherry, Gene (4 June 2011). "Tyson Gay runs year's fastest 100 metres". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- "Thompson breaks record". guardian.co.tt. Trinidad and Tobago Guardian. 22 June 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Roy Jordan (4 July 2016). "Six world leads on third day of US Olympic Trials". IAAF. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- "Burrell Eclipses 100-Meter Mark". Los Angeles Times. 7 July 1994. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Janofsky, Michael (26 August 1991). "He Paces Back In a Blazing 9.86". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- "Diamond League: Asafa Powell runs 100m in 9.81 seconds". bbc.com. BBC. 5 July 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Jason Henderson (18 May 2019). "Noah Lyles edges Christian Coleman in Shanghai sprint showdown". Athletics Weekly. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Bret Bloomquist (7 June 2019). "Oduduru leads Texas Tech track to first-ever men's NCAA championship". El Paso Times. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Bob Ramsak; Alfons Juck (22 August 2018). "Baker clocks 9.87 world lead in Chorzow". iaaf.org. IAAF. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- Markham, Carl; Butler, Mark (17 May 2019). "Bolt runs 14.35 sec for 150m; covers 50m-150m in 8.70 sec!". iaaf.org. IAAF. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "100m World Record falls to Montgomery – 9.78!". iaaf.org. IAAF. 14 September 2002. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- "CAS decision on Montgomery and Gaines". iaaf.org. IAAF. 13 December 2005. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Nikitaridis, Michalis (14 June 2005). "Powell keeps his World record promise". iaaf.org. IAAF. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- "Chambers to lose medal and record". bbc.co.uk. BBC. 26 June 2006. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- Myers, Sanjay (22 November 2011). "Banned for life! – Doping panel shows sprinter Mullings no mercy". Jamaica Observer. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "Justin Gatlin Ran 9.45 With Crazy Wind-Aid on Japanese TV". flotrack.org. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- Zinser, Lynn (30 June 2008),"Shattering Limits on the Track, and in the Pool" The New York Times

- Ewing, Lori (The Canadian Press) (18 June 2017), National Post

- "All-time women's best 100m". IAAF. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- "All-time women's best 100m". alltime-athletics.com. 25 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Sherdon Cowan (1 July 2016). "#NatlTrials: Elaine Thompson storms to 10.70s win in 100m". jamaicaobserver.com. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Jenna West (8 June 2019). "LSU Freshman Breaks Women's 100m Collegiate Record in 10.75, Celebrates Early". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Cathal Dennehy (11 June 2016). "Ahoure powers to African 100m record of 10.78 in Florida". IAAF. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- "100m Results" (PDF). IAAF. 24 August 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- "100m Results". NAAATT. 24 June 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- Pritchard, W. G. (July 2006). "Mathematical Models of Running". SIAM Review. 35 (3): 359–379. doi:10.1137/1035088.

- Linthorne, Nick (March 2003). "Wind Assistance". Brunel University. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2008.

- http://www.iaaf.org/statistics/toplists/inout=o/age=n/season=0/sex=W/all=y/legal=A/disc=100/detail.html

- "U20 Outdoor 100 Metres Men". worldathletics.org. World Athletics. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Jon Gugala (14 June 2014). "Freshman Sprinting Phenom Wins NCAAs, Sets World Junior Record". deadspin.com. Dead Spin. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- Jon Mulkeen (29 April 2013). "Kiryu equals World junior 100m record in Hiroshima". iaaf.org. IAAF. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- Jon Mulkeen (19 May 2019). "Norman, Wang and Lalova break meeting records in Osaka". IAAF. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- "58th ANNUAL MT. SAC RELAYS Results – Friday Field" (PDF). mtsacrelays.com. Mt. San Antonio College. 15 April 2016. p. 10. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "Sprinter Sani Brown outlcasses field in 100-meter final for first national title". Japan Times. 24 June 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- "Results 100 Metres Men – Round 1" (PDF). iaaf.org. IAAF. 4 August 2017. p. 1. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "Simbine scorches to 9.91 100m victory in Pretoria". World Athletics. 14 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Todd Grasley (19 May 2014). "Bromell Blazing! World Leading 9.77w (4.2) To Win Big 12 Championship". milesplit.com. FloSports, Inc. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "IAAF denies Kiryu share of junior world record". Japan Times. 15 June 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Donald McRae (15 February 2004). "Athletics: An interview with Mark Lewis-Francis". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Bill Buchalter (26 May 1990). "Neal Puts Speedy Reputation On The Line At Showalter Field". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "U20 Outdoor 100 Metres Women". worldathletics.org. World Athletics. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Jon Mulkeen (20 June 2015). "Hill breaks world youth 100m best and American junior record with 10.98". IAAF. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- "100m Results" (PDF). results.toronto2015.org. 22 July 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Jon Mulkeen (22 April 2018). "Terry breezes to 10.99 at Mt SAC Relays". IAAF. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Anthony Foster (8 June 2019). "Kiara Grant recaptures NJR with 11.04s". Trackalerts.com. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- "100m Results". NAAATT. 24 June 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- Noel Francis (22 June 2019). "Thompson beats Fraser-Pryce to Jamaican 100m title as both clock 10.73". IAAF. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Gillen, Nancy (1 September 2019). "Jamaican teenage sprint star Williams faces ban for failed doping test". Inside the Games. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Raynor, Kayon; Osmond, Ed (26 September 2019). "Jamaica's Williams escapes doping ban". Reuters. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "ATHLETE PROFILE Briana WILLIAMS". World Athletics. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "U18 Outdoor 100 Metres Men". worldathletics.org. World Athletics. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "100m Results". deltatiming.com. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- Phil Minshull (7 September 2015). "Leotlela clocks second fastest ever youth 100m with 10.20 in Samoa". IAAF. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Noel Francis (25 March 2018). "Taylor and Davis delight at Jamaica's Boys and Girls Champs". IAAF. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- Raymond Graham (6 March 2016). "Matherson sprints to National Youth record". jamaica-gleaner.com. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- "U20 Outdoor 100 Metres Women". worldathletics.org. World Athletics. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Florida's Whitney sets world junior 200 record". newsobserver.com. 7 July 2014. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- "World Para Athletics World Records". IPC. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- "100m Results" (PDF). sportresult.com. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- "Men's T35 100m Round 1 Heat 2 Results" (PDF). Rio 2016 official website. 9 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "INDONESIA 2018 ASIAN PARA GAMES – Para Athletics – RESULTS" (PDF). Asian Para Games. p. 33. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "Men's 100m T37 Round 1 Heat 2 Results" (PDF). Rio 2016 official website. 10 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "Men's 100m T38 Results" (PDF). Rio 2016 official website. 13 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- "World Para Athletics World Records". IPC. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- "Women's 100m T11 Semifinal 2 Results" (PDF). Rio 2016 official website. 9 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "Women's 100m T12 Results" (PDF). Rio 2016 official website. 9 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "Women's 100m T13 Results" (PDF). Rio 2016 official website. 11 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "Women's 100m T42 Results" (PDF). IPC. 30 October 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- "Women's 100m T43/44 Results" (PDF). IPC. 29 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- "Super seven in Nottwil". paralympic.org. 25 May 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- "Women's T53 100m – Round 1 Heat 1 Results" (PDF). Rio 2016 official website. 8 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- Marion Jones admitted to having taken performance enhancing drugs prior to the 2000 Summer Olympics. She relinquished her medals to the United States Olympic Committee, and the International Olympic Committee formally stripped her of her medals.

- 100 metres

- not awarded

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 100 metres. |