Serbian literature

Serbian literature (Serbian: Српска књижевност/Srpska književnost) refers to literature written in Serbian and/or in Serbia and all other lands where Serbs reside. The history of Serbian literature begins with the independent theological works from the Nemanjić era. With the fall of Serbia and neighboring countries in the 15th century, there is a gap in the literary history in the occupied land, however, Serbian literature continued uninterrupted in lands under European rule and saw a revival in the 18th century in Vojvodina, then under Habsburg rule. Serbia gained independence following the Serbian Revolution (1804–1815) and Serbian literature has since prospered.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Serbia |

|---|

|

| People |

|

Traditions

|

|

Mythology and folklore

|

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

|

Art

|

|

Literature

|

|

Media |

| Sport |

|

Monuments

|

|

Organisations |

|

History

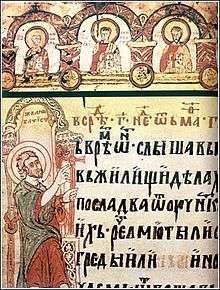

Medieval literature

The Old Church Slavonic literature was created on Byzantine model, and at first church services and biblical texts were translated into Slavic, and soon afterward other works for Christian life values (including Latin works) from which they attained necessary knowledge in various fields. Although this Christian literature educated the Slavs, it did not have an overwhelming influence on original works. Instead, a more narrow aspect, the genres, and poetics with which the cult of saints could be celebrated were used, owing to the Slavic celebration of Cyril and Methodius and their Slav disciples as saints and those responsible for Slavic literacy. The ritual genres were hagiographies, homiletics and hymnography, known in Slavic as žitije (vita), pohvala (eulogy), službe (church services), effectively meaning prose, rhetoric, and poetry. The fact that the first Slavic works were in the canonical form of ritual literature, and that the literary language was the ritual Slavic language, defined the further development. Medieval Slavic literature, especially Serbian, was modeled on this classical Slavic literature. The new themes in Serbian literature were all created within the classic ritual genres.[1]

The earliest writings in Serbian were, obviously, religious in nature. Religions were historically the first institutions that persisted despite political and military upheavals, as well as the first organizations to see the value in writing down their history and policies. Serbia's early religious documents date back as we know to the 10th and 11th centuries. In the 12th century the art form of religious writing was developed by Saint Sava, who worked to bring about an artistic aspect to these writings, also based on earlier works, that is still appreciated today.

Early modern period

Post-Medieval Serbian literature was dominated by folk songs and epics passed orally from generation to generation. Historic events, such as the Battle of Kosovo in the 14th century play a major role in the development of the Serbian epic poetry. The epic and lyrical poetry, the drama, and the prose of every class, all alike sound those notes, and the melody is triumphant or despairing according to the period of the nation's struggles against its many invaders. Less perhaps than any other European literature has Serbian literature been influenced by the literature of other lands. It mirrors throughout the simple, unsophisticated feeling and thoughts of men and women who love their country wholly, sincerely, faithfully, and are ready to lay down their lives to preserve its freedom. Here, if ever, the soul of a people is revealed in its most challenging time in history while attempting to extricate itself from centuries of Eastern (Turkish) and Western (Austrian, Hungarian, Venetian and Napoleonic French) oppression.

Baroque and Classicism

Serbian literature in Vojvodina continued building onto Medieval tradition, influenced by Old Serbian, Russian baroque and Serbian baroque of Vojvodina, which culminated in the Slavonic-Serbian language. Most important authors of the time are Dimitrije Ljubavić, Đorđe Branković, Vasilije III Petrović-Njegoš, Gavril Stefanović Venclović, Mojsije Putnik, Pavle Julinac, Jovan Rajić, Zaharije Orfelin, and many others.

Romanticism and Realism

Before the start of a fully established Romanticism concomitant with the Revolutions of 1848, some Romanticist ideas (e.g. the usage of national language to rally for national unification of all classes) were developing, especially among monastic clergy in Vojvodina. The most prominent representative of that is Dositej Obradović, who gave up his monastic vows and left for decades of wandering, occasionally studying, teaching, or working in the cultural field in countries as variegated as Russia, England, Germany, Albania, Ottoman Turkey and Italy, and ending up as a Minister of Education in the Principality of Serbia.

After winning the independence from the Ottoman Empire, the Serbian independence movement sparked the first works of modern Serbian literature. Most notably Petar II Petrović Njegoš and his Mountain Wreath of 1847, represent a cornerstone of the Serbian epic, which was based on the rhythms of the folk songs.

Furthermore, Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, an acquaintance of J. W. von Goethe, became the first person to collect folk songs and epics and to publish them in a book. Vuk Karadžić is regarded as the premier Serbian philologist, who together with Đuro Daničić played a major role in reforming the modern Serbian language.

Modern literature

The literary trend of the first and second decade of the 20th century is referred to as Moderna in Serbian. Its influences came from leading literature movements in Europe, particularly that of symbolism and the psychological novel, but more through mood and aesthetic component rather than of literary craftsmanship. It was manifested in the works of Jovan Dučić and Milan Rakić, the two poet diplomats. The third leading poet at the time was Aleksa Šantić whose poetry was less subtle but filled with pathos, emotion, and sincerity. They were popular for their patriotic, romantic and social overtones.

Other poets such as Veljko Petrović, Milutin Bojić, Sima Pandurović, Vladislav Petković Dis, Milorad Mitrović, Stevan M. Luković, Vladimir Stanimirović, Danica Marković, Velimir Rajić, Stevan Besević, Milorad Pavlović-Krpa, Milan Ćurčin, Milorad Petrović Seljančica, all took different paths and showed great sophistication and advancement not only in their craft but in their world view as well. Most of them were pessimistic in their outlook, while at the same time patriotic in the wake of turbulent events that were then culminating in the struggle for Old Serbia, the Balkan Wars and World War I.

A new generation of prose writers also made themselves felt, namely Svetozar Ćorović, Janko Veselinović, Veljko M. Milićević, and Borisav Stanković with his major works, Nečista krv (Impure Blood) and Koštana (drama). Impure Blood is now considered one of the most powerful Serbian novels of the period. His was the world of the tradition-laden town of Vranje, where Slavs were divided among themselves as to who they were—Serbian, Bulgarian, Greek or the newly-created ethnicity, Macedonian (a resurrected Macedonia of ancient times, no doubt)? This place of merchants and landowners was on its way out together with the retreating Turks from the region, after the long struggle for Old Serbia from 1903-1911 and the Balkan Wars. Equally, Svetozar Ćorović depicted his native Herzegovina, where the shift in the Moslem population during the Bosnian crisis and after was most acute. Simo Matavulj and Ivo Ćipiko penned a landscape of the South Adriatic not always sunny and blue. Ćipiko's lyrical writings warned the reader of the deteriorating social conditions, especially in "The Spiders". Then came Petar Kočić's highly lyrical prose and the quest for the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina and its natural unification with Serbia. In Kočić's play "The Badger Before the Court", the Austro-Hungarian authorities are mocked for their proclivity to rule over others, including Slavs.

All these writers were backed by Serbian critics educated in the West. For example, Bogdan Popović, Pavle Popović, Ljubomir Nedić, Slobodan Jovanović, Branko Lazarević, Vojislav Jovanović Marambo and Jovan Skerlić. Skerlić with his chef-d'oeuvre, the historical survey of Serbian literature, and Bogdan Popović, with his refined, Western-schooled aestheticism, not only weighed the writers’ achievements but also pointed out the directions of modern world literature to them.

Several writers from this period—Milutin Uskoković, Velimir Rajić, Milutin Bojić, and Vladislav Petković Dis and others—made the ultimate sacrifice during World War I, adding to the enormous toll Serbia had to pay for its hard-earned victory, only to enter into an unworkable confederacy with others that dissolved in 1941 and again in 1991.

In the 20th century, Serbian literature flourished and a myriad of young and talented writers appeared.

The most well known authors are Ivo Andrić, Miloš Crnjanski, Meša Selimović, Borislav Pekić, Branko Miljković, Danilo Kiš, Milorad Pavić, David Albahari, Miodrag Bulatović, Igor Marojević, Miroslav Josić Višnjić, Dobrica Ćosić, Zoran Živković, Vladimir Arsenijević, Vladislav Bajac and many others. Jelena Dimitrijević and Isidora Sekulić are two early twentieth century women writers. Svetlana Velmar-Janković and Gordana Kuić are the best known female novelists in Serbia today.

Milorad Pavić is perhaps the most widely acclaimed Serbian author today, most notably for his Dictionary of the Khazars (Хазарски речник / Hazarski rečnik), which has been translated into 24 languages.

Notable works

- English translations of some of the important pieces of modern Serbian literature

- Andric, Ivo, The Bridge on the Drina, The University of Chicago Press, 1977.

- Andric, Ivo, Damned Yard and Other Stories , edited and translated by Celia Hawkesworth, Dufour Editions, 1992.

- Andric, Ivo, The Slave Girl and Other Stories, edited and translated by Radmila Gorup, Central European University Press, 2009.

- Andric, Ivo, The Days of the Consuls, translated by Celia Hawkesworth, Dereta, 2008.

- Bajac, Vladislav. Hamam Balkania, translated by Randall A. Major, Geopoetica Publishing, 2009.

- Kis, Danilo, A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, translated by Duska Mikic-Mitchell, Penguin Books, 1980.

- Kis, Danilo, The Encyclopedia of the Dead, translated by Michael Henry Heim, 1983.

- Pekic, Borislav, The Time of Miracles, translated by Lovett F. Edwards, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1976.

- Pekic, Borislav, The Houses of Belgrade, translated by Bernard Johnson, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1978.

- Pekic, Borislav, How to Quiet a Vampir: A Sotie (Writings from an Unbound Europe), translated by Stephen M. Dickey and Bogdan Rakic, Northwestern University Press, 2005

- Selimovic, Mesa, Death and the Dervish, translated by Bogdan Rakic and Stephen M. Dickey, Northwestern University Press, 1996.

References

Sources

- Desnica, Gojko (1983). Književnost srpskog naroda 1170-1940. Zajednica pisaca.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Deretić, Jovan (1995). "Literature in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries". The history of Serbian Culture. Rastko.

- Deretić, Jovan (1983). Историја српске књижевности. Нолит.

- Deretić, Jovan (1996). Put srpske književnosti: identitet, granice, težnje. Srpska književna zadruga.

- Kadić, Ante (1964). Contemporary Serbian Literature. Mouton.

- Kleut, Marija (2001). Српска народна књижевност. Издавачка књижарница Зорана Стојановића.

- Marinković, Radmila (1995). "Medieval literature". The history of Serbian Culture. Rastko.

- Palavestra, Predrag (1986). Историја модерне српске књижевности: Златно доба 1892-1918. Српска књижевна задруга.

- Pavić, Milorad (1970). Istorija srpske knjiz̆evnosti baroknog doba: (XVII i XVIII vek). Nolit.

- Petković, Novica (1995). "Twentieth century literature". The history of Serbian Culture. Rastko.

- Popović, Pavle (1999). Преглед српске књижевности. Завод за уџбенике и наставна средства. ISBN 978-86-17-07491-1.

- Živković, Dragiša (2004). Српска књижевност у европском оквиру. Српска књижевна задруга.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Serbian literature. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Selected Literatures and Authors Page - Serbian, Montenegrin, and Yugoslav Literature

- A brief overview of Serbian Literature

- Slavic Literature Resources from the Slavic Reference Service, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

- Istorijska biblioteka: Serbian Medieval Literature

- A Quick Guide to Serbian Literature (in English)