Salvadorans

Salvadorans (Spanish: Salvadoreños), also known as Salvadorians, are people who identify with El Salvador, a country in Central America. Salvadorans are mainly Mestizos (mixed European and Amerindian heritage) who make up the bulk of the population in El Salvador. Most Salvadorans live in El Salvador, although there is also a significant Salvadoran diaspora, particularly in the United States, with smaller communities in other countries around the world.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 9.5–10 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,310,784 (2017)[3] | |

| 918,619 (2006)[4] | |

| 70,000 (2006)[4] | |

| 63,965 (2011)[5] | |

| 32,130 (2006)[4] | |

| 30,000 (2006)[4] | |

| 28,015 (2006)[4] | |

| 17,135 (2014)[6] | |

| 15,000 (2006)[4] | |

| 8,000 (2006)[4] | |

| 3,500 (2006)[4] | |

| 3,223 (2019)[7] | |

| 3,200 (2006)[4] | |

| 1,230 (2019)[8] | |

| 1,225 (2019)[8] | |

| 1,037 (2019)[8] | |

| 137,449 (2006)[4] | |

| Rest of the world | 19,285 (2006)[4] |

| Languages | |

| Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, Protestantism[9] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Salvadorian American, Mestizo, Spaniards, Mayans, Afro-Salvadoran | |

El Salvador's population was 6,218,000 in 2010, compared to 2,200,000 in 1950.[10] In 2010, the percentage of the population below the age of 15 was 32.1%, 61% were between 15 and 65 years of age, while 6.9% were 65 years or older.[10]

Demonym

Salvadoreño/a in Spanish and in English Salvadoran is the accepted and most commonly used term for referring people of Salvadoran ancestry. However, both Salvadorian and Salvadorean are widely used terms in daily life by English-speaking Salvadoran citizens living in the United States and other English-speaking countries. Both words can be seen in most Salvadoran business signs in the United States and else where in the world. This is because the sounds "ia" and "ea" in Salvadorian and Salvadorean sound more closely to the "ñ" sound in the Spanish term Salvadoreño.

Centroamericano/a in Spanish and in English Central American is an alternative standard and widespread cultural identity term that Salvadorans use to identify themselves, along with their regional isthmian neighbours. It is a secondary demonym and it is widely used as an interchangeable term for El Salvador and Salvadorans. The demonym Central American is an allusion to the strong union that the Central America region has had since its independence. The term Central America is not only a regional cultural identity, but also a political identity, since the region has been united on various occasions as a single country such as the United Provinces of Central America, Federal Republic of Central America, National Representation of Central America, and Greater Republic of Central America. The same can be said for El Salvador's neighbors, specifically the original five states of Central America.

Nicknames

Salvi is an informal demonym referring to the Salvadoran people and their culture, specifically to overseas born Salvadorans in the diaspora located in the United States. The word is formed by Anglonization and taking the first five letters of the affectionate diminutive hypocorism form of Salvador (Salvita) to a shorten form "Salvi", with plural being Salvis. The slang term Salvi was coined and used for self-identification by the first generation wave of Salvadoran Americans born in the United States from parents who had escaped the civil war in the 1980s, and has been used as a term of endearment. The term has been widely used and is in mainstream usage particularly among younger members and masses of the Salvadoran American sector. The term Salvi is preserved in a very positive light when compared to its other older counterparts and predecessors such as Guanaco and Salvatrucha which have fallen into disuse among Salvadoran Americans, regarded as derogatory and negative. The term Cuscatleco is reserved for older generations of Salvadorans, specifically those born in El Salvador.

Outside the United States and especially within El Salvador itself the term Guanaco is still commonly used and isn't considered offensive. It's used much in the same way Salvi is used among Salvadoran Americans, it's regarded as a term of endearment among Salvadorans especially those within El Salvador itself.

National Symbols

| Type | Symbol | Year | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthem | National Anthem of El Salvador |

1879 | |

| Flag and Coat of arms | Coat of arms of El Salvador and Flag of El Salvador |

1912 |  |

| Color | Cobalt blue and white |

1912 | |

| Bird | Turquoise-browed motmot |

1999 | .jpg) |

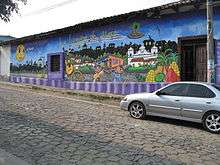

| Art | La Palma style Art |

| |

| Music | Xuc |

| |

| National Dish | Pupusa |

.jpg) | |

| Flower | Yucca gigantea |

2003 | |

| Tree | Tabebuia rosea |

1939 |  |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | Joya de Ceren |

1993 | _sm_(4290048784).jpg) |

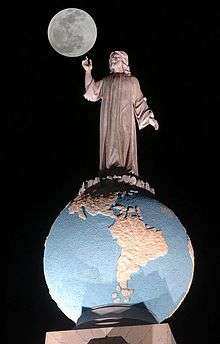

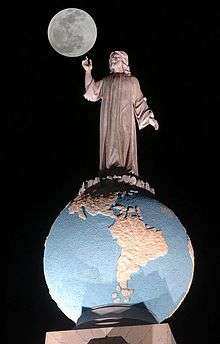

| Patron and National Personification | Monumento al Divino Salvador del Mundo |

| |

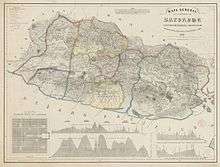

Native Homeland

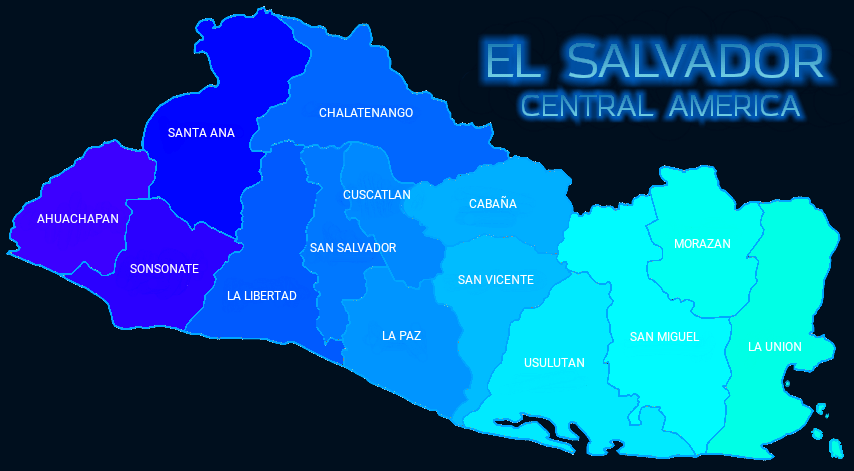

Salvadorans inhabit the lush Central American nation of El Salvador. El Salvador is one of the seven country in the giant isthmus of Central America. The surface of El Salvador features tropical forest, jungles, mountains, volcanoes, plains (savanna), rivers, lagoons, lakes, calderas and the Pacific Ocean. The forests of El Salvador contain a wide diversity of flora and fauna. El Salvador is a home to ecosystems, biomes, living, nonliving natural resources and also home to a plethora of diverse species. In terms of nonliving resources, El Salvador contains rich volcanic soil, fertile earth that gives life to lush vegetation. Native vegetation such as Yucca gigantea, Cassava, Fernaldia pandurata and Crotalaria longirostrata which are used in Salvadoran food. El Salvador also contains gold under its surface, however all type of mining has been abolished in El Salvador. The Native American indigenous ancestors of Salvadorans, have been living in the region for thousands of years. El Salvador is periodically hit with earthquakes and tropical storms, occasionally but rarely by cyclones.

History

Lithic era

El Salvador was inhabited by Paleo-Indians, the first peoples who subsequently inhabited, the Americas during the glacial episodes of the late Pleistocene period. Their intriguing paintings (the earliest of which date from 8000 BC) can still be seen and marveled at in caves outside the towns of Corinto and Cacaopera, both in Morazán. Originating in the Paleolithic period, these cave paintings exhibit the earliest traces of human life in El Salvador; these early Native Americans people used the cave as a refuge, Paleoindian artists created cave and rock paintings that are located in present-day El Salvador.

The Lencas later occupied the cave and utilised it as a spiritual place. Other ancient petroglyphs called piedras pintadas (rock paintings) include la Piedra Pintada in San Jose Villanueva, La Libertad and the piedra pintada in San Isidro, Cabañas. The rock petroglyphs in San Jose Villanueva near a cave in (Walter Thilo Deininger National Park) are similar to other ancient rock petroglyph around the country. Regarding the style of the engravings it has been compared by with the petroglyphs of La Peña Herrada (Cuscatlán), el Letrero del Diablo (La Libertad) and la Peña de los Fierros (San Salvador). We can add to the list the sites in Titihuapa, the Cave of Los Fierros and La Cuevona both in ( Cuscatlán ).

Archaic Period

Native Americans appeared in the Pleistocene era and became the dominant people in the Lithic stage, developing in the Archaic period in North America to the Formative stage, occupying this position for thousands of years until their demise at the end of the 15th and 16th century, spanning the time of the original arrival in the Upper Paleolithic to European colonization of the Americas during the early modern period.

About 40,000 years ago the ancestors of the indigenous people of the Americas split from the rest of the world following the Pleistocene megafauna and then they flourish mightily, evolving in the Americas, from the Lithic stage to the Post-Classic stage, which was brought into an abrupt end about 525 years ago with the infamous mass genocide and cultural extinction caused by Europeans intrusion into the Americas, bringing diseases and colonizing the Americas with warfare, terrorism, extremists radical Christianity and mass massacres. Only some Native American indigenous groups survived that catastrophe, most of them in Mexico, Central America and South America, with Salvadoran indigenous being one of many who have given rise to all modern Native Americans still alive today.

Mesoamerican-Isthmus cultures

- Ancient Mesoamerican sites in El Salvador

- Mayan artifacts of El Salvador

Late Classic Maya cup from El Salvador. 600–900 AD.

Late Classic Maya cup from El Salvador. 600–900 AD.- Mayan artifact found at the Joya de Cerén archaeological site

- Mayan artifact found at the Joya de Cerén archaeological site

Late Classic Maya bowl, El Copador style, El Salvador.

Late Classic Maya bowl, El Copador style, El Salvador. Late Postclassic ceramic vessel from El Salvador, with face decoration. 1200–1520 AD.

Late Postclassic ceramic vessel from El Salvador, with face decoration. 1200–1520 AD. Late Classic Maya vessel from El Salvador, 600–900 AD

Late Classic Maya vessel from El Salvador, 600–900 AD Late Classic Maya plate, El Salvador.

Late Classic Maya plate, El Salvador. Late Classic Maya bowl from El Salvador.

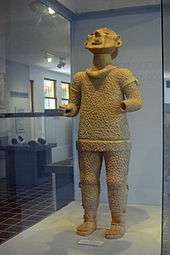

Late Classic Maya bowl from El Salvador. Tazumal's Xipe Totec.

Tazumal's Xipe Totec.

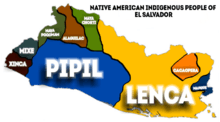

Historically El Salvador has had diverse Native American cultures, coming from the north and south of the continent along with local populations mixed together. El Salvador belongs to both to the Mesoamerican region in the western part of the country, and to the Isthmo-Colombian Area in the eastern part of the country, where a myriad of indigenous societies have lived side by side for centuries with their unique cultures and speaking different indigenous languages of the Americas in the beginning of the Classic stage.

The Lenca people are an indigenous people of eastern El Salvador where population today is estimated at about 37,000. The Lenca was a matriarchal society and was one of the first civilizations to develop in El Salvador and were the first major civilization in the country. The pre-Conquest Salvadoran Lenca had frequent contact with various Maya groups as well as other indigenous peoples of Central America. The origin of Lenca populations has been a source of ongoing debate amongst anthropologists and historians. Throughout the regions of Lenca occupation, Lenca pottery is a very distinguishable form of Pre-Columbian art. Handcrafted by Lenca women, Lenca pottery is considered an ethnic marking of their culture. Some scholars have suggested that the Lenca migrated to the Central American region from South America around 3,000 years ago, making it the oldest civilization in El Salvador. Guancasco is the annual ceremony by which Lenca communities, usually two, gather to establish reciprocal obligations in order to confirm peace and friendship. Quelepa is a major site in eastern El Salvador. Its pottery shows strong similarities to ceramics found in central western El Salvador and the Maya highlands. The Lenca sites of Yarumela, Los Naranjos in Honduras, and Quelepa in El Salvador, all contain evidence of the Usulután-style ceramics.

The Cacaopera people are an indigenous people in El Salvador who are also known as the Matagalpa or Ulua. Cacaopera people spoke the Cacaopera language, a Misumalpan language. Cacaopera is an extinct language belonging to the Misumalpan family, formerly spoken in the department of Morazán in El Salvador. It was closely related to Matagalpa, and slightly more distantly to Sumo, but was geographically separated from other Misumalpan languages.

The Xinca people, also known as the Xinka, are a non-Mayan indigenous people of Mesoamerica, with communities in the western part of El Salvador near its border. The Xinka may have been among the earliest inhabitants of western El Salvador, predating the arrival of the Maya and the Pipil. The Xinca ethnic group became extinct in the Mestizo process.

El Salvador has two Maya groups, the Poqomam people and the Ch'orti' people. The Poqomam are a Maya people in western El Salvador near its border. Their indigenous language is also called Poqomam. The Ch'orti' people (alternatively, Ch'orti' Maya or Chorti) are one of the indigenous Maya peoples, who primarily reside in communities and towns of northern El Salvador. The Maya once dominated the entire western portion of El Salvador, up until the eruption of the lake ilopango super volcano. Mayan ruins are the most widely conserved in El Salvador and artifacts such as Maya ceramics Mesoamerican writing systems Mesoamerican calendars and Mesoamerican ballgame can be found in all Maya ruins in El Salvador which include Tazumal, San Andrés, El Salvador, Casa Blanca, El Salvador, Cihuatan, and Joya de Ceren.

Alaguilac people were a former indigenous group located on northern El Salvador. Their language is unclassified. The Alagüilac language is an undocumented indigenous American language that is now extinct. The Alaguilac ethnic group became extinct during the Mestizo process.

The Mixe people is an indigenous group that inhabited the western borders of El Salvador. They spoke the Mixe languages which are classified in the Mixe–Zoque family, The Mixe languages are languages of the Mixean branch of the Mixe–Zoquean language family. The Mixe ethnic group became extinct during the Mestizo process.

The Mangue people, also known as Chorotega, spoke the Mangue language, a now-extinct Oto-Manguean language. They were indigenous to eastern El Salvador border, near the gulf.

The Pipil people are an indigenous people who live in western El Salvador. Their language is called Nahuat or Pipil, related to the Toltec people of the Nahua peoples and were speakers of early Nahuatl languages. However, in general, their mythology is more closely related to the Maya mythology, who are their near neighbors and by oral tradition said to have been adopted by Ch'orti' and Poqomam Mayan people during the Pipil exodus in the 9th century CE. The culture lasted until the Spanish conquest, at which time they still maintained their Nawat language, despite being surrounded by the Maya in western El Salvador. By the time the Spanish arrived, Pipil and Poqomam Maya settlements were interspersed throughout western El Salvador. The Pipil are known as the last indigenous civilization to arrive in El Salvador, being the least oldest and were a determined people who stoutly resisted Spanish efforts to extend their dominion southward. The Pipil are direct descendants of the Toltecs, but not of the Aztecs.

Evidence of Olmec civilization presence in western El Salvador can be found in the ruin sites of Chalchuapa in the Ahuachapan department. Olmec petroglyphs can be found on boulders in Chalchuapa portraying Omlec warriors with helmets identical to those found on the Olmec colossal heads. This suggest that the area was once an Olmec enclave, before fading away for unknown reasons. The Olmecs are believed to have lived in present-day El Salvador as early as 2000 BC. The 'Olmec Boulder, ' is a sculpture of a giant head found near Casa Blanca, El Salvador site in Las Victorias near Chalchuapa. "Olmecoid" figurins such as the Potbelly sculpture have been found through this area, in fact most are described as looking primeval proto-Olmec.

16th century

At the time of the Spanish conquest, the area was composed of several indigenous states of the Post-Classic stage who resisted the Europeans as Central America was ravaged by epidemics of diseases, sometimes the Spanish purpously resorted to spreading diseases such as smallpox, measles, and cholera. Smallpox was only the first epidemic. Typhus in 1546, influenza and smallpox together in 1558, smallpox again in 1589, diphtheria in 1614, measles in 1618—all ravaged the remains of any indigenous force.

Pipil resistance battle

The Spanish traveled to Central America in the 15th century to discover a lush world, which was inhabited by many Native American indigenous civilizations. To the cultures of Europe, Central America was mysterious, primal and terrifying. El Salvador has lush, tropical rainforests that cover much of its volcanic surface and the geology of El Salvador is strongly affected by the presence of volcanoes, ellecuent with highly nutritious soil full of mineral, excellent for agriculture. These properties made it highly valued by Europeans, who exploited it for transport back to Spain. When the Europeans began to search El Salvador for valuable metals, the natives were appalled and angered by the destruction of their tropical home and felt that the damage done by Europeans in the pursuit of underground metals was nothing more than senseless destruction that violated the basic tenets of their beliefs. The expansion of the Spanish mining colony and smallpox threatened the continued existence of the indigenous natives in El Salvador. Despite its small size, El Salvador had a plethora of diverse civilizations with many languages and cultures, but expansion of the Spanish colony threatened the continued existence of the Lenca, Maya and Pipil, Native American people indigenous to El Salvador.

When Pedro de Alvarado arrived in the Cuzcatlan kingdom, he saw that all civilians, women, children and elders, in towns and large urban centers had been mandatorily evacuated to a safe unknown location. The warriors of Cuzcatan had deployed to their battle stations in Acajutla and waited for Pedro de Alvarado and his forces in that coastal city. Pedro de Alvarado approached confident trusting that the result was going to be like in Mexico and Guatemala where the people saw them as gods, and thought he was going to easily defeat this new indigenous force because his Mexican allies and the Pipil of Cuzcatlan spoke a similar language and communication was going to be easy and fast. However unlike in Mexico and Guatemala, the Indigenous peoples of El Salvador never saw the Spanish as gods, but as foreign, gold lusting, barbaric, alien invaders who would resort to anything to steal away their land. Once Pedro de Alvarado arrived, he saw the shock troops of the Cuzcatlan kingdom in Acajutla ready for battle, he saw that the Cuzcatan force had a significantly large number of soldiers, which easily outnumbers his Spanish soldiers and Mexican Indian allies, once he saw this he order his army for the first time to quickly retreat, but the Cuzcatlec army was not satisfied by this and made a decisive shock and awe attack on the Spanish army, running behind them war chanting and shooting bow arrows, Pedro de Alvarado had no choice but to fight to survive. Pedro de Alvarado describes the Cuzcatlec soldiers in great detail with shields made of colorful exotic feathers, a vest-like armor made of three inch cotton which arrows could not penetrate and large spears. The Cuzcatlec soldiers were so fully armed, that those who were wounded by the Spanish guns and swords, found it difficult to get up because of their wounds and heavy armor. Both armies suffered great casualties, a wounded Pedro de Alvarado retreated losing a lot of men especially close Mexican Indian auxiliaries. Once his army had gathered Pedro de Alvarado decided to head to the Cuzcatlan metropolis capital; however, half way the same Cuzcatlan army was waiting for them.

Wounded, unable to fight and hiding in the cliffs, Pedro de Alvarado sent his Spanish men on their horses to approach the Cuzcatlec platoons to see if they would fear the horses, however the Indigenous warriors stood their ground and did not move an inch, as Pedro de Alvarado recalls in his letters to Hernan Cortez. Pedro de Alvarado was so stunned and imprinted with their monumental military power and size which he described as large number of male warriors in colorful feather armors and long spears, a large army of indigenous men which eerily spooked him. The Cuzcatlec shock troops made another decisive shock and awe attacked on the Spanish on which both sides lost men, but this time Pedro de Alvarado lost many Spaniards, horses, and weapons which the Natives of Cuzcatlan had taken.

Pedro de Alvarado retreated and sent Mexican Indian messengers to communicate with the Cuzcatlan warriors, Pedro de Alvarado sent for them to return the stolen weapons and to surrender to the Spanish king, to which the Cuzcatecs responded with the famous response, "If you want your weapons, come get them". As days passed, Pedro de Alvarado, fearing an ambush, sent more Mexican Indian messengers to negotiate, but these messenger never came back and were presumably executed. The Spanish efforts were firmly resisted by the indigenous people, including the Lenca and their Mayan-speaking neighbors, defeated the Spaniards and what was left of their Mexican Tlaxcala Indian allies, forcing them to withdraw to Guatemala, it was Pedro de Alvarado first defeat.

After being wounded, Alvarado abandoned the war and appointed his brother, Gonzalo de Alvarado, to continue the task. Two subsequent expeditions (the first in 1525, followed by a smaller group in 1528) brought the Pipil under Spanish control, since the Pipil also were weakened by a regional epidemic of smallpox. In 1525, the conquest of Cuzcatlán was completed and the city of San Salvador was established. The Spanish faced much resistance from the Pipil and were not able to reach eastern El Salvador, the area of the Lencas.

Lenca resistance battle

In 1526 the Spanish founded the garrison town of San Miguel , headed by another explorer and conquistador, Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, nephew of Pedro Alvarado. Oral history holds that a Lenca crown princess, Antu Silan Ulap I, organized resistance to the conquistadors.

The kingdom of Lenca was alarmed by de Moscoso's invasion, and Antu Silan travelled from village to village, uniting all the Lenca towns in present-day El Salvador and Honduras against the Spaniards. Through surprise attacks and overwhelming numbers, they were able to drive the Spanish out of San Miguel and destroy the garrison.

For ten years the Lencas prevented the Spanish from building a permanent settlement. Then the Spanish returned with more soldiers, including about 2,000 forced conscripts from indigenous communities in Guatemala. They pursued the Lenca leaders further up into the mountains of Intibucá.

Antu Silan Ulap eventually handed over control of the Lenca resistance to Lempira (also called Empira). Lempira was noteworthy among indigenous leaders in that he mocked the Spanish by wearing their clothes after capturing them and using their weapons captured in battle. Lempira fought in command of thousands of Lenca forces for six more years in El Salvador and Honduras until he was killed in battle. The remaining Lenca forces retreated into the hills. The Spanish were then able to rebuild their garrison town of San Miguel in 1537.

Historical evidence and census supports the explanation of "strong sexual asymmetry", as a result of a strong bias favoring matings between European males and Native American females, and to the important indigenous male mortality during the Conquest. The genetics thus suggests the native men were sharply reduced in numbers due to the war and disease. Large numbers of Spaniard men settled in the region and married or forced themselves with the local women. The Natives were forced to adopted Spanish names, language, and religion, and in this way, the Lencas and Pipil women and children were Hispanicized. A vast majority over 90% of Salvadorans are Mestizo/Native American. Conservative figures say the Mestizo and Native American populations make up 87% of the populations and semi-Liberal figures say that the Native American population reaches upwards to 13% of the population plus the high percentage of Mestizo making El Salvador a highly Native American nation.

Post-colonization

- Historical figures of El Salvador

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

The history of El Salvador has been a struggle against many conquistadors, empires, dictatorships and world powers that would seal El Salvador's fate in the future. After gaining independence, several Spanish Creoles took control of the government and economy. El Salvador's population was further put into stress, turmoil, frustration, and ire which would condition a society with a cycle of a never ending violent nature. Feliciano Ama and Anastasio Aquino, king of the Nonoualquenos, led a rebellions against what was referred to as an abuse of power and corruption, but it was repressed by the government with genocide. These occurrences would also motivate Prudencia Ayala, Farabundo Martí and ultimately Óscar Romero.

This repression would have repercussions for the future of El Salvador. La matanza 1932 Salvadoran peasant massacre, and all the liberation movements from the 1930s to 1980s, Salvadoran Civil War and even the current Mara (gang) phenomenon would emerge from the injustices committed by Spanish rule, Creoles, and other foreign power interventions.

The 1932 Salvadoran peasant massacre occurred on January 22 of that year, in the western departments of El Salvador when a brief peasant-led rebellion was suppressed by the government, then led by Maximiliano Hernández Martínez. The Salvadoran army, being vastly superior in terms of weapons and soldiers, executed those who stood against it. The rebellion was a mixture of protest and insurrection and ended in ethnocide, claiming the lives of anywhere between 10,000 and 40,000 peasants and other civilians, many of them indigenous people.

The Salvadoran Civil War was a conflict between the military-led government of El Salvador and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), a coalition or "umbrella organization" of five left-wing guerrilla groups. A coup on October 15, 1979, led to the killings of anti-coup protesters by the government as well as anti-disorder protesters by the guerrillas, and is widely seen as the tipping point toward civil war. The full-fledged civil war lasted for more than 12 years and saw extreme violence from both sides. It also included the deliberate terrorizing and targeting of civilians by death squads, recruitment of child soldiers and other violations of human rights, mostly by the military. An unknown number of people disappeared during the conflict, and the UN reports that more than 75,000 were killed.

On top of the recurring natural disasters such as massive destructive earthquakes, cyclonic systems and volcanic activity, the constant war atmosphere in El Salvador including the prehistoric wars in Mesoamerica times the colonization of the Spaniards, the independence wars, the oppression of later ruthless dictatorships, the 1932 indigenous massacre, the Central American proxy wars in the 70's, the civil war in El Salvador in the 1980s and the current gang war, have all put a heavy hinder-age in the development of El Salvador and left the Salvadoran society vulnerable and prone to interpersonal violence

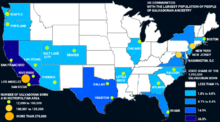

The exodus of Salvadorans was a result of both economic and political problems. The largest immigration wave occurred as a result of the Salvadoran Civil War in the 1980s, in which 20%-30% of El Salvador's population emigrated. About 50% percent, or up to 500,000 of those who escaped the country headed to the U.S., which was already home to over 10,000 Salvadorans. The number of Salvadoran immigrants in the United States continued to grow in the 1990s and 2000s as a result of family reunification and new arrivals fleeing a series of natural disasters that hit El Salvador, including earthquakes and hurricanes. Gang warfare, which made El Salvador one of the dangerous countries in the world, also contributed to the surge of immigrants seeking asylum in the late part of the 2000s and the first four years in the 2010 decade, by 2008, there were about 1.1 million Salvadoran immigrants in the United States.

Growth of the population

- Salvadoran population

Population density in Central America

Population density in Central America Salvadoran population in the United States

Salvadoran population in the United States

- Salvadoran people

.jpg) Salvadoran troops

Salvadoran troops Salvadoran baseball players

Salvadoran baseball players.jpg) Young Salvadoran man playing a guitar

Young Salvadoran man playing a guitar.jpg) Salvadoran women San Vicente, El Salvador

Salvadoran women San Vicente, El Salvador Salvadoran refugee children during the civil war, 1987

Salvadoran refugee children during the civil war, 1987_2013_in_Metalio%2C_El_Salvador%2C_May_18%2C_2013_130518-A-IA672-087.jpg) Salvadoran boy

Salvadoran boy.jpg) Young Salvadoran women in Ahuachapan

Young Salvadoran women in Ahuachapan- Salvadoran model Irma Dimas from Sonsonate

Salvadoran boy in La Libertad, La Libertad

Salvadoran boy in La Libertad, La Libertad.jpg) Salvadoran boy in San Pedro Perulapán

Salvadoran boy in San Pedro Perulapán.jpg) Salvadoran boys in San Pedro Perulapán

Salvadoran boys in San Pedro Perulapán.jpg) Salvadoran boys coloring, San Pedro Perulapán

Salvadoran boys coloring, San Pedro Perulapán

El Salvador has the largest population density in Latin America, and is the third most populated country in Central America after Honduras and Guatemala, from the 2005 census, the population exceeds 6 million. The total impact of civil wars, dictatorships and socioeconomics drove over a million Salvadorans (both as immigrants and refugees) into the United States; Guatemala is the second country that hosts more Salvadorans behind the United States, approximately 110,000 Salvadorans according to the national census of 2010.[11] in addition small Salvadoran communities sprung up in Canada, Australia, Belize, Panama, Costa Rica, Italy, and Sweden since the migration trend began in the early 1970s.[12] The 2010 U.S. Census counted 1,648,968 Salvadorans in the United States, up from 655,165 in 2000.[13] By 2017, the figured had risen to over 2.3 million.[3]

| Total population (x 1000) |

Proportion aged 0–14 (%) |

Proportion aged 15–64 (%) |

Proportion aged 65+ (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 2 200 | 42.7 | 53.3 | 4.0 |

| 1955 | 2 433 | 43.6 | 52.6 | 3.8 |

| 1960 | 2 773 | 45.1 | 51.1 | 3.7 |

| 1965 | 3 244 | 46.3 | 50.1 | 3.7 |

| 1970 | 3 736 | 46.4 | 49.9 | 3.6 |

| 1975 | 4 232 | 45.8 | 50.5 | 3.7 |

| 1980 | 4 661 | 45.2 | 50.9 | 3.9 |

| 1985 | 5 004 | 44.1 | 51.8 | 4.2 |

| 1990 | 5 344 | 41.7 | 53.7 | 4.6 |

| 1995 | 5 748 | 39.6 | 55.5 | 4.9 |

| 2000 | 5 959 | 38.3 | 56.2 | 5.5 |

| 2005 | 6 073 | 35.7 | 58.1 | 6.2 |

| 2010 | 6 218 | 32.1 | 61.0 | 6.9 |

Racial and ethnic groups

- Salvadorans

.jpg) Salvadoran boy

Salvadoran boy.jpg) Salvadoran children

Salvadoran children.jpg) Salvadoran boy playing guitar

Salvadoran boy playing guitar.jpg) Salvadoran women

Salvadoran women

El Salvador's population numbers 6,377,358. Ethnically, 86.3% of Salvadorans are mixed (mixed Indigenous Native American and European Spanish origin). Another 12.7% is of pure European descent, other 10% are pure Native American indigenous descent, 0.13% black people and others 0.64%.

Mestizo Salvadorans

86.3% of the population are mestizo, having mixed Native American indigenous and European ancestry.[14] In the mestizo population, Salvadorans who are racially European, especially Mediterranean, as well as Afro-Salvadoran, and the Native American people in El Salvador who do not speak indigenous languages or have and indigenous culture, all identify themselves as being culturally mestizo.

Native American Indigenous Salvadorans

According to the Salvadoran Government, about 10% of the population are of full indigenous origin. The largest most dominant Native American groups in El Salvador are the Lenca people, Cacaopera people, Maya peoples: (Poqomam people/Chorti people) and Pipil people. The small culture enclaves of the Xinca people, Alaguilac people, Mixe people, and Mangue language have become extinct through the Mestizo process. The country also had an Olmec past. There are small populations of Cacaopera people in the Morazán Department and a few Ch'orti' people live in the department of Ahuachapán, near the border of Guatemala.

The number of indigenous people in El Salvador have been criticized by indigenous organizations and academics as too small and accuse the government of denying the existence of indigenous Salvadorans in the country. Nonetheless, very few Amerindians have retained their customs and traditions, having over time assimilated into the dominant Mestizo/Spanish culture. The low numbers of indigenous people may be partly explained by historically high rates of old-world diseases, absorption into the mestizo population, as well as mass murder during the 1932 Salvadoran peasant uprising (or La Matanza) which saw (estimates of) up to 30,000 peasants killed in a short period of time. Many authors note that since La Matanza the indigenous in El Salvador have been very reluctant to describe themselves as such (in census declarations for example) or to wear indigenous dress or be seen to be taking part in any cultural activities or customs that might be understood as indigenous. Departments and cities in the country with notable indigenous populations include Sonsonate (especially Izalco, Nahuizalco, and Santo Domingo), Cacaopera, and Panchimalco, in the department of San Salvador.

White Salvadorans

Some 12.7% of Salvadorans are white. This population is mostly made up of ethnically Spanish people, while there are also Salvadorans of French, German, Swiss, English, Irish, and Italian descent. In northern departments like the Chalatenango Department, it is well known that residents in the area are of pure Spanish descent; The governor of San Salvador, Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet, ordered families from northern Spain (Galicia and Asturias) to settle the area to compensate for the lack of indigenous people to work the land; it is not uncommon to see people with blond hair, fair skin, and blue or green eyes in municipalities like Dulce Nombre de María, La Palma, Nueva Concepcion and El Pital.

Arab Salvadorans

There is a significant Arab population (of about 100,000);[15] mostly from Palestine (especially from the area of Bethlehem), but also from Lebanon. Salvadorans of Palestinian descent numbered around 70,000 individuals, while Salvadorans of Lebanese descent is around 25,000.[16] There is also a small community of Jews who came to El Salvador from France, Germany, Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey.

The history of the Arabs in El Salvador dates back to the end of the 20th century, because of religious clashes, which induced many Palestinians, Lebanese, Egyptians and Syrians to leave the land where they were born, in search of countries where they at least lived in An atmosphere of relative peace. There were also other reasons of a subjective nature, based on the hope of success, of achieving success and fortune and obtaining recognition from others.

Arab immigration in El Salvador began at the end of the 20th century in the wake of the repressive policies applied by the Ottoman Empire against Maronite Catholics. Several of the destinations that the Lebanese chose at that time were in countries of the Americas, including El Salvador. This resulted in the Arab diaspora residents being characterized by forging in devoutly Christian families and very attached to their beliefs, because in these countries they can exercise their faith without fear of persecution, which resulted in the rise of Lebanese-Salvadoran, Syrian-Salvadoran and Palestinian-Salvadoran communities in El Salvador.[17]

Currently the strongest community is the Palestinian (70,000 descendants), followed by the Lebanese settled in San Salvador with more than 27,000 direct descendants, mostly (95%) Catholic and Orthodox Christians. The slaughter of Lebanese and Palestinian Arab Christians at the hands of Muslims, initiated the first Lebanese migration to El Salvador.[18]

Inter-ethnic marriage in the Lebanese community with Salvadorans, regardless of religious affiliation, is very high; most have only one father with Lebanese nationality and mother of Salvadoran nationality. As a result, some of them speak Arabic fluently. But most, especially among younger generations, speak Spanish as a first language and Arabic as a second.[19]

During the war between Israel and Lebanon in 1948 and during the Six Day War, thousands of Lebanese left their country and went to El Salvador. First they arrived at La Libertad, were they comprised half of the economic activity of immigrants.

Lebanon had been an iqta of the Ottoman Empire. Although the imperial administration, whose official religion was Islam, guaranteed freedom of worship for non-Muslim communities, and Lebanon in particular had a semi-autonomous status, the situation for practitioners of the Maronite Catholic Church was complicated, since they had to cancel exaggerated taxes and suffered limitations for their culture. These tensions were expressed in a rebellion in 1821 and a war against the Druze in 1860. The hostile climate caused many Lebanese to sell their property and take ships in the ports of Sidon, Beirut and Tripoli heading for the Americas.

Statistically in El Salvador, there are about 120,000 Arabs, of Lebanese, Syrian, Egyptian and Palestinian ancestry. In the case of these Arab-Salvadorans, although not all the families arrived together, they were the ones that lead the economy in the country.

In 1939, the Arab community based in San Salvador organized and founded the "Arab Youth Union Society"[20]

Pardo Salvadorans

Pardo is the term that was used in colonial El Salvador to describe a tri-racial Afro-Mestizo person of Indigenous, European, and African descent. Afro-Salvadorans are the descendants of the African population that were enslaved and shipped to El Salvador to work in mines in specific regions of El Salvador. They have mixed into and were naturally bred out by the general Mestizo population, which is a combination of a Mestizo majority and the minority of Pardo people, both of whom are racially mixed populations. Thus, there remains no significant extremes of African physiognomy among Salvadorans like there is in the other countries of Central America. A total of only 10,000 African slaves were brought to El Salvador over the span of 75 years, starting around 1548, about 25 years after El Salvador's colonization. El Salvador is the only country in Central America that does not have English Antillean (West Indian) or Garifuna populations of the Caribbean, but instead had older colonial African slaves that came straight from Africa. This is the reason why El Salvador is the only country in Central America not to have a caribbeanized culture, and instead preserved its classical Central America culture.

Other

In the 2007 census, 0.7% of the population was considered as "other".[21] There are up to 100,000 Nicaraguans living in El Salvador.[22]

Language

- Languages of El Salvador

El Salvador was home to Mayan Script

El Salvador was home to Mayan Script

Spanish is the language spoken by virtually all inhabitants. Spanish (official), Salvadoran Sign Language, Pipil (Nawat) , Kekchí. Immigrant languages include Chinese, Arabic, Poqomam, and American Sign Language.[23]

Literacy

- definition: age 10 and over can read and write

- total: 95.0%[24]

- male: 94.4%

- female: 95.5%

- urban: 97.2%

- rural: 91.8%

Religion

- Cathedrals in El Salvador

Iglesia El Rosario, San Salvador

Iglesia El Rosario, San Salvador

- Iglesia Don Rua, San Salvador

- Iglesia El Calvario, San Salvador

Basílica del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús, San Salvador

Basílica del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús, San Salvador

- Iglesia Santa Lucía, Suchitoto

Church in Dulce Nombre de María

Church in Dulce Nombre de María Iglesia El Carmen, Santa Ana, El Salvador

Iglesia El Carmen, Santa Ana, El Salvador Iglesia Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, Ahuachapán

Iglesia Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, Ahuachapán

There is diversity of religious beliefs in El Salvador. The majority of the population is Christian.[25] Roman Catholics (47%) and Evangelicals (33%) are the two major denominations in the country.[9] Those not affiliated with any religious group amount to 17% of the population.[9] The remainder of the population (3%) is made up of Jehovah's Witnesses, Hare Krishnas, Muslims, Jews, Buddhists, Latter-day Saints, and those adhering to indigenous religious beliefs.[9]

Culture

- El Salvador arts and crafts

La Palma-type art, from La Palma, Chalatenango

La Palma-type art, from La Palma, Chalatenango- Arts and craft from Ilobasco

- La Palma-type art form from Santa Ana, El Salvador

- Mesoamerican souvenirs from Juayua

.jpg) La Palma-Style art on modern Salvadoran building in San Salvador

La Palma-Style art on modern Salvadoran building in San Salvador Handcraft bag from Ataco

Handcraft bag from Ataco Hand crafted bookmarks from La Palma

Hand crafted bookmarks from La Palma- Salvadoran staple art in La Palma

- Salvadoran Culture

Salvadpran hammocks from Morazán Department

Salvadpran hammocks from Morazán Department.jpg) Salvadoran children dressed for Calabuiza on day of the dead

Salvadoran children dressed for Calabuiza on day of the dead.jpg) Young Salvadoran girls in San Miguel, El Salvador

Young Salvadoran girls in San Miguel, El Salvador- Fire ball festival in Nejapa

The town of Concepción de Ataco

The town of Concepción de Ataco colonial houses of Suchitoto

colonial houses of Suchitoto Colorful cemetery San Miguel, El Salvador

Colorful cemetery San Miguel, El Salvador

The culture of El Salvador is a Central American culture nation influenced by the clash of ancient Mesoamerica and medieval Iberian Peninsula. Salvadoran culture is influenced by Native American culture (Lenca people, Cacaopera people, Maya peoples, Pipil people) as well as Latin American culture (Latin America, Hispanic America, Ibero-America). Mestizo culture and the Catholic Church dominates the country. Although the Romance language, Castilian Spanish, is the official and dominant language spoken in El Salvador, Salvadoran Spanish which is part of Central American Spanish has influences of Native American languages of El Salvador such as Lencan languages, Cacaopera language, Mayan languages and Pipil language, which are still spoken in some regions of El Salvador

Mestizo culture dominates the country, heavy in both Native American Indigenous and European Spanish influences. A new composite population was formed as a result of intermarrying between the native Mesoamerican population of Cuzcatlan with the European settlers. The Catholic Church plays an important role in the Salvadoran culture. Archbishop Óscar Romero is a national hero for his role in resisting human rights violations that were occurring in the lead-up to the Salvadoran Civil War.[26] Significant foreign personalities in El Salvador were the Jesuit priests and professors Ignacio Ellacuría, Ignacio Martín-Baró, and Segundo Montes, who were murdered in 1989 by the Salvadoran Army during the height of the civil war.

Painting, ceramics and textiles are the principal manual artistic mediums. Writers Francisco Gavidia (1863–1955), Salarrué (Salvador Salazar Arrué) (1899–1975), Claudia Lars, Alfredo Espino, Pedro Geoffroy Rivas, Manlio Argueta, José Roberto Cea, and poet Roque Dalton are among the most important writers from El Salvador. Notable 20th-century personages include the late filmmaker Baltasar Polio, female film director Patricia Chica, artist Fernando Llort, and caricaturist Toño Salazar.

Amongst the more renowned representatives of the graphic arts are the painters Augusto Crespin, Noe Canjura, Carlos Cañas, Giovanni Gil, Julia Díaz, Mauricio Mejia, Maria Elena Palomo de Mejia, Camilo Minero, Ricardo Carbonell, Roberto Huezo, Miguel Angel Cerna, (the painter and writer better known as MACLo), Esael Araujo, and many others. For more information on prominent citizens of El Salvador, check the List of Salvadorans.

Notable Salvadoran people

McLeod Bethel-Thompson is an American football quarterback who is a free agent. He played college football at Sacramento State.

McLeod Bethel-Thompson is an American football quarterback who is a free agent. He played college football at Sacramento State. Jorge Cañas was a Salvadoran football player.

Jorge Cañas was a Salvadoran football player. Emerson Hernández is a Salvadorean race walker.

Emerson Hernández is a Salvadorean race walker. Darwin Cerén is a Salvadoran footballer who plays for the Major League Soccer club San Jose Earthquakes and is captain of the El Salvador national team

Darwin Cerén is a Salvadoran footballer who plays for the Major League Soccer club San Jose Earthquakes and is captain of the El Salvador national team- Arturo Álvarez (footballer, born 1985) is a Salvadoran American footballer who plays as a winger and forward for Major League Soccer club Chicago Fire

Dustin Corea is a Salvadoran international footballer who plays for FC Edmonton.

Dustin Corea is a Salvadoran international footballer who plays for FC Edmonton..jpg) Eriq Zavaleta is an American soccer player who plays as a center back for Toronto FC of Major League Soccer.

Eriq Zavaleta is an American soccer player who plays as a center back for Toronto FC of Major League Soccer. Steve Purdy is a Salvadoran American footballer who plays as a defender for Orange County Blues in the USL. He has played for the El Salvador national team at the CONCACAF Gold Cup in 2011 and 2013.

Steve Purdy is a Salvadoran American footballer who plays as a defender for Orange County Blues in the USL. He has played for the El Salvador national team at the CONCACAF Gold Cup in 2011 and 2013.

_(28133946721).jpg) Marcelo Arévalo is a professional Salvadoran tennis player

Marcelo Arévalo is a professional Salvadoran tennis player Jaime Alas is a Salvadoran professional footballer

Jaime Alas is a Salvadoran professional footballer Rodolfo Zelaya is a Salvadoran professional footballer

Rodolfo Zelaya is a Salvadoran professional footballer Rafael Burgos is a Salvadoran professional forward

Rafael Burgos is a Salvadoran professional forward Marcos Villatoro is a writer from the United States. He is the author of six novels, two collections of poetry and a memoir, and the producer/director of the documentary “Tamale Road: A Memoir from El Salvador.”

Marcos Villatoro is a writer from the United States. He is the author of six novels, two collections of poetry and a memoir, and the producer/director of the documentary “Tamale Road: A Memoir from El Salvador.”.jpg) Nayib Bukele is a Salvadoran politician and businessman

Nayib Bukele is a Salvadoran politician and businessman Francisco Rubio (astronaut) is a US Army helicopter pilot, flight surgeon, and NASA astronaut candidate of the class of 2017.

Francisco Rubio (astronaut) is a US Army helicopter pilot, flight surgeon, and NASA astronaut candidate of the class of 2017. Johnny Wright is a Salvadoran politician

Johnny Wright is a Salvadoran politician Mauricio Interiano is a Salvadoran politician

Mauricio Interiano is a Salvadoran politician Carlos Calleja is a Salvadoran politician

Carlos Calleja is a Salvadoran politician José Atilio Benítez Parada is Salvadoran General, ambassador and former Minister of Defense.

José Atilio Benítez Parada is Salvadoran General, ambassador and former Minister of Defense. Roberto José d'Aubuisson Munguía is a Salvadoran politician

Roberto José d'Aubuisson Munguía is a Salvadoran politician.jpg) Juan Jose Daboub is the chairman and CEO of The Daboub Partnership, Founding Chief Executive Officer of the Global Adaptation Institute and former managing director of the World Bank (2006–2010)

Juan Jose Daboub is the chairman and CEO of The Daboub Partnership, Founding Chief Executive Officer of the Global Adaptation Institute and former managing director of the World Bank (2006–2010).jpg) Mauricio Funes is a Salvadoran politician who was President of El Salvador from June 1, 2009 to June 1, 2014

Mauricio Funes is a Salvadoran politician who was President of El Salvador from June 1, 2009 to June 1, 2014- Luciana Sandoval is a Salvadoran presenter, dancer and former model.

Somaya Reece is a Salvadoran American hip hop and reality TV star

Somaya Reece is a Salvadoran American hip hop and reality TV star- Christy Turlington is an American supermodel. Her mother is from El Salvador. She first represented Calvin Klein's Eternity campaign in 1989 and again in 2014 and also represents Maybelline.

Sabi (singer) is a Salvadoran-American pop singer, songwriter, dancer and actress from Los Angeles, California. She was formerly part of the hip hop girl group, The Bangz. She is currently signed to Warner Bros. Records.

Sabi (singer) is a Salvadoran-American pop singer, songwriter, dancer and actress from Los Angeles, California. She was formerly part of the hip hop girl group, The Bangz. She is currently signed to Warner Bros. Records. Ana Yancy Clavel is a Salvadorian beauty queen and TV personality

Ana Yancy Clavel is a Salvadorian beauty queen and TV personality Carla Vila is a Salvadoran American actress

Carla Vila is a Salvadoran American actress Elizabeth Espinosa reporter and journalist

Elizabeth Espinosa reporter and journalist Fernando del Valle is an American operatic tenor.

Fernando del Valle is an American operatic tenor. Allison Iraheta is an American singer from Los Angeles, California, who was the fourth place finalist on the eighth season of American Idol.

Allison Iraheta is an American singer from Los Angeles, California, who was the fourth place finalist on the eighth season of American Idol..jpg) Victor R. Ramirez is the current state senator for District 47 in Prince George's County, Maryland

Victor R. Ramirez is the current state senator for District 47 in Prince George's County, Maryland J. R. Martinez is an American actor, motivational speaker and former U.S. Army soldier. Starting in 2008, he played the role of Brot Monroe on the ABC daytime drama All My Children. He is the winner of Season 13 of ABC's Dancing with the Stars. Martinez served as the Grand Marshal of the 2012 Rose Parade. He is currently costarring on the syndicated action series SAF3.

J. R. Martinez is an American actor, motivational speaker and former U.S. Army soldier. Starting in 2008, he played the role of Brot Monroe on the ABC daytime drama All My Children. He is the winner of Season 13 of ABC's Dancing with the Stars. Martinez served as the Grand Marshal of the 2012 Rose Parade. He is currently costarring on the syndicated action series SAF3. Markos Moulitsas is a Salvadoran American that served in the U.S. Army from 1989 through 1992. He is the founder and publisher of Daily Kos, a blog focusing on liberal and Democratic Party politics in the United States. He co-founded SB Nation, a collection of sports blogs, which is now a part of Vox Media

Markos Moulitsas is a Salvadoran American that served in the U.S. Army from 1989 through 1992. He is the founder and publisher of Daily Kos, a blog focusing on liberal and Democratic Party politics in the United States. He co-founded SB Nation, a collection of sports blogs, which is now a part of Vox Media Carlos Irigoyen Ruiz was a renowned Salvadoran musician during the 1920s-1940s.

Carlos Irigoyen Ruiz was a renowned Salvadoran musician during the 1920s-1940s. Evelyn García is a Salvadoran cycle racer who rides for the Fenixs team.

Evelyn García is a Salvadoran cycle racer who rides for the Fenixs team. Herbert Sosa is a Salvadoran professional footballer.

Herbert Sosa is a Salvadoran professional footballer. Ricardo Saprissa was a lifelong athlete, coach, and promoter of sports.

Ricardo Saprissa was a lifelong athlete, coach, and promoter of sports..jpeg) Rosemary Casals is a former American professional tennis player

Rosemary Casals is a former American professional tennis player Richard Menjívar is a Salvadoran international footballer currently playing for the New York Cosmos of the North American Soccer League.

Richard Menjívar is a Salvadoran international footballer currently playing for the New York Cosmos of the North American Soccer League. Edwin Miranda grew up in Los Angeles, California and played four years of college soccer at Cal State-Northridge, where he was twice named Big West Conference Defender of the Year.

Edwin Miranda grew up in Los Angeles, California and played four years of college soccer at Cal State-Northridge, where he was twice named Big West Conference Defender of the Year. Hala Ayala is an cybersecurity specialist and democrat politician representing the 51st district in the Virginia House of Delegates.

Hala Ayala is an cybersecurity specialist and democrat politician representing the 51st district in the Virginia House of Delegates. Maribel Arrieta Gálvez was a Salvadoran beauty queen where she represented her country at Miss Universe 1955. Arrieta met Baron Jacques Thuret (of Belgian/French nobility) and both were married in 1963, granting her the title "Baronesa de Thuret".

Maribel Arrieta Gálvez was a Salvadoran beauty queen where she represented her country at Miss Universe 1955. Arrieta met Baron Jacques Thuret (of Belgian/French nobility) and both were married in 1963, granting her the title "Baronesa de Thuret".

References

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "US Census Bureau 2017 American Community Survey B03001 1-Year Estimates HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY SPECIFIC ORIGIN". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- "El Salvador en el Mundo 2006". Archivo.elsalvador.com. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "2011 National Household Survey Profile - Province/Territory". 12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Australian Government - Department of Immigration and Border Protection. "Salvadorian Australians". Immi.gov.au. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "Befolkning efter födelseland, ålder och kön. År 2000 - 2019". scb.se. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- "El Salvador - Emigrantes totales". datosmacro.expansion.com/. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "International Religious Freedom Report for 2012". U.S. State Department. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- "Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision". Esa.un.org. Archived from the original on 6 May 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "Institución". Ine.gob.gt. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "Mapa de las Migraciones Salvadoreñas". Pnud.org.sv. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "CIA - The World Factbook -- El Salvador". CIA. Retrieved 2013-10-12.

- Zielger, Matthew. "El Salvador: Central American Palestine of the West?". The Daily Star. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- "Lebanese Diaspora – Worldwide Geographical Distribution". Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- "The Palestinians of El Salvador". AJ Plus. May 29, 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-11-13.

- "Why So Many Palestinians Live In El Salvador". newsvideo.su. May 26, 2019.

- "Lebanese Diaspora – Worldwide Geographical Distribution". theidentitychef.com. September 6, 2009. Archived from the original on 2013-12-24.

- Hugh Dellios (March 21, 2004). "El Salvador vote divides 2 Arab clans". Chicago Tribune.

- Ethnic Groups -2007 official Census. Page 13. Digestyc.gob.sv

- "The Nicaragua case_M Orozco2 REV.doc" (PDF). Thedialogue.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- "El Salvador". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "Reports - Human Development Reports" (PDF). Hdr.undp.org. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- The Latin American Socio-Religious Studies Program / Programa Latinoamericano de Estudios Sociorreligiosos (PROLADES) PROLADES Religion in America by country, Prolades.com

- Eaton, Helen-May (1991). The impact of the Archbishop Óscar Romero's alliance with the struggle for liberation of the Salvadoran people: A discussion of church-state relations (El Salvador) (M.A. thesis), Wilfrid Laurier University

- "Ed Weeks is Salvadorean on his mother's side!", latina.com. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- "In Bed With Joan – Episode 9: Ed Weeks". Retrieved 24 August 2014.