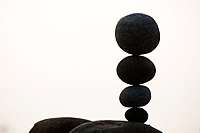

Rock balancing

Rock balancing or stone balancing (stone or rock stacking) is an art, discipline, or hobby in which rocks are naturally balanced on top of one another in various positions without the use of adhesives, wires, supports, rings or any other contraptions which would help maintain the construction's balance. The number of rock piles created in this manner in natural areas has recently begun to worry conservationists because they can misdirect hikers, expose the soil to erosion, aesthetically intrude upon the natural landscape, and serve no purpose.[1][2]

.jpg)

Description

Rock balancing can be a performance art, a spectacle, or a devotion, depending upon the interpretation by its audience. Essentially, it involves placing some combination of rock or stone in arrangements which require patience and sensitivity to generate, and which appear to be physically impossible while actually being only highly improbable. The rock balancer may work for free or for pay, as an individual or in a group, and their intents and the audiences' interpretations may vary given the situation or the venue.

Rock balancing has also been described as a type of problem solving, and some artists consider it as a skill in awareness. Some work has been described as a magic trick for the mind.[3] As with other forms of independent public art, some installations may be created in remote areas where there may be little or no audience.[4] A cairn, used to mark trails, is also a collection of stacked rocks, but these are typically more durable.

Styles

- Rock Stacking – rocks laid flat upon each other to great height.

- Classic balance – each rock balanced inline.

- Counterbalance – lower rocks depend on the weight of upper rocks to maintain balance.

- Arch – rocks form a structure that spans a space. Similar to the architecture of ancient stone bridges.

- Free style – a combination of two or more of the above.

Rock stacking

Rock stacking Classic balance

Classic balance Free style

Free style

(counterbalance and classic balance).jpg) An arch

An arch

(with classic balance detail)

Events

.jpg)

The annual Llano Earth Art Festival in Texas includes a rock stacking competition called the "Rock Stacking World Championship," held on the banks of the Llano River. Competitions during the 2020 edition include "tallest rock stack", "best rock balancer", "best rock arch builder", "most rocks in a single tower", and "most artistic rock stack design".[5]

In context of math and physics

The stability of a rock structure depends on the location of each rock's center of mass in relation to its support points. If other rocks are also on top or contacting it at any point, then the forces (due to weight) of other rocks also play a role. For an individual rock to be stable, it usually requires at least three contact points to rest on, forming a "tripod." Generally, the closer together the points in the tripod, the less stable the rock will be (thus making it more precarious, and becoming a rock balance sculpture - and many would argue more beautiful). Based on position and shape, a rock may also be stable even when resting on only a single point. A rock at the top of a sculpture, for example, can have a rounded shape, but be approximately flat and oriented horizontally, and be in a state of equilibrium.[nb 1][6]

The stability of a structure is also affected by the friction between rocks, especially when rocks are set upon one another at an angle. A structure may topple over (collapse) based on the magnitude of other phenomena, such as wind, rain, snow, and localized ground vibration, or general seismic activity.

Opposition

Some visitors to natural areas who wish to experience nature in its undisturbed state object to this practice, especially when it intrudes on public spaces such as national parks, national forests and state parks.[7] The practice of rock balancing is claimed to be able to be made without changes to nature; environmental artist Lila Higgings has defended it as compatible with leave-no-trace ideals if rocks are used without impacting wildlife and are later returned to their original places,[8] and some styles of rock balancing are short-lived. However, "disturbing or collecting natural features (plants, rocks, etc.) is prohibited" in U.S. national parks because these acts may harm the flora and fauna dependent on them.[9]

Some outdoor enthusiasts are also in opposition as rock stacks or "cairns" are traditionally used for the purpose of navigation in some back woods trails. Having ornamental rock stacks may confuse those who rely on them as trail markers.

Notable artists

- Adrian Gray, UK artist specialising in stone balancing sculptures and photography

- Andy Goldsworthy, artist for whom rock balancing is a minor subset of his "Collaborations with Nature"

- Bill Dan, American artist

- Michael Grab, balance artist and photographer, born Alberta, Canada[10]

Gallery

Brazil

Brazil Canada

Canada Colombia

Colombia

(A natural formation in El Tuparro National Park) Czech Republic

Czech Republic.jpg) England

England India

India Italy

Italy Spain

Spain Taiwan

Taiwan Turkey

Turkey.jpg) United States

United States Rock Stack - Australia

Rock Stack - Australia

Notes

- A rock with such a shape (for example a spheroid) would be in static equilibrium when it is oriented horizontally. If pushed its center of mass would rise, producing a leveling moment and returning the rock to its equilibrium position. This is similar to how a Roly-poly or Weeble toy is stable when resting on a single point, and rights itself after being pushed.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rock balancing. |

- Street art

- Yarn bombing

- Environmental art

- Jenga (a game requiring skill to balance wood blocks)

References

- Fessenden, Marissa (July 13, 2020). "Conservationists Want You to Stop Building Rock Piles". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- Barkham, Patrick (August 17, 2018). "Stone-stacking: cool for Instagram, cruel for the environment". The Guardian. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- Champion, Brandon (May 4, 2017). "Great Lakes artist's rock balancing a 'magic trick' for the mind". MLive. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- The World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti, Rafael Schacter, 2013, ISBN 0300199422.

- "Rockstacking". Llano Earth Art Festival. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- John L Synge & Byron A Griffith (1949). Principles of Mechanics (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- "Home – Leave No Trace". lnt.org. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- Newman, Andy (July 3, 2008). "It's Not Easy Picking a Path to Enlightenment". The New York Times.

- "Park Regulations – Canyonlands National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". nps.gov. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- Krulwich, Robert (January 5, 2013). "A Very, Very, Very Delicate Balance". NPR. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

External links

- Llano Earth Art Festival – A rock balancing event.

- Rock Balancing is both art and advocacy. By Reuters . Philippines. August 2011.

- Stuart Finch – Rock Balancing Act. By Sarah Phelan. Metro Santa Cruz. March 2001.

- Gilles Charrot – L'homme qui murmure a l'oreille des pierres Martine Schnoering. September 15, 2009.

- Rock Balancing in worldwide images – photos of all styles and practitioners.

- Rock Balancing promotes environmentalism – videos.

- Links + google map to a worldwide community of rock balancers – Explore more rock balancers around the world.