Beauty

Beauty is the ascription of a property or characteristic to an animal, idea, object, person or place that provides a perceptual experience of pleasure or satisfaction. Beauty is studied as part of aesthetics, culture, social psychology and sociology. An "ideal beauty" is an entity which is admired, or possesses features widely attributed to beauty in a particular culture, for perfection. Ugliness is the opposite of beauty.

The experience of "beauty" often involves an interpretation of some entity as being in balance and harmony with nature, which may lead to feelings of attraction and emotional well-being. Because this can be a subjective experience, it is often said that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder."[1] Often, given the observation that empirical observations of things that are considered beautiful often align among groups in consensus, beauty has been stated to have levels of objectivity and partial subjectivity which are not fully subjective in their aesthetic judgement.

Ancient Greek

The classical Greek noun that best translates to the English-language words "beauty" or "beautiful" was κάλλος, kallos, and the adjective was καλός, kalos. However, kalos may and is also translated as ″good″ or ″of fine quality″ and thus has a broader meaning than mere physical or material beauty. Similarly, kallos was used differently from the English word beauty in that it first and foremost applied to humans and bears an erotic connotation.[2]

The Koine Greek word for beautiful was ὡραῖος, hōraios,[3] an adjective etymologically coming from the word ὥρα, hōra, meaning "hour". In Koine Greek, beauty was thus associated with "being of one's hour".[4] Thus, a ripe fruit (of its time) was considered beautiful, whereas a young woman trying to appear older or an older woman trying to appear younger would not be considered beautiful. In Attic Greek, hōraios had many meanings, including "youthful" and "ripe old age".[4]

The earliest Western theory of beauty can be found in the works of early Greek philosophers from the pre-Socratic period, such as Pythagoras. The Pythagorean school saw a strong connection between mathematics and beauty. In particular, they noted that objects proportioned according to the golden ratio seemed more attractive.[5] Ancient Greek architecture is based on this view of symmetry and proportion.

Plato considered beauty to be the Idea (Form) above all other Ideas.[6] Aristotle saw a relationship between the beautiful (to kalon) and virtue, arguing that "Virtue aims at the beautiful."[7]

Classical philosophy and sculptures of men and women produced according to the Greek philosophers' tenets of ideal human beauty were rediscovered in Renaissance Europe, leading to a re-adoption of what became known as a "classical ideal". In terms of female human beauty, a woman whose appearance conforms to these tenets is still called a "classical beauty" or said to possess a "classical beauty", whilst the foundations laid by Greek and Roman artists have also supplied the standard for male beauty and female beauty in western civilization as seen, for example, in the Winged Victory of Samothrace. During the Gothic era, the classical aesthetical canon of beauty was rejected as sinful. Later, Renaissance and Humanist thinkers rejected this view, and considered beauty to be the product of rational order and harmonious proportions. Renaissance artists and architects (such as Giorgio Vasari in his "Lives of Artists") criticised the Gothic period as irrational and barbarian. This point of view of Gothic art lasted until Romanticism, in the 19th century.

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, Catholic philosophers like Thomas Aquinas included beauty among the transcendental attributes of being. In his Summa Theologica, Aquinas described the three conditions of beauty as: integritas (Wholeness), consonantia (harmony), claritas (radiance of form)[8]

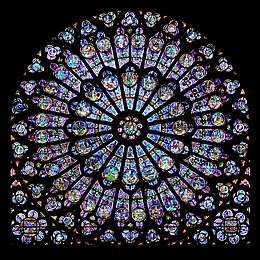

In the Gothic Architecture of the High and Late Middle Ages, light was considered the most beautiful revelation of God, which was heralded in design. Examples are the stained glass of Gothic Cathedrals including Notre-Dame de Paris and Chartes Cathedral.

Age of Reason

The Age of Reason saw a rise in an interest in beauty as a philosophical subject. For example, Scottish philosopher Francis Hutcheson argued that beauty is "unity in variety and variety in unity".[9] The Romantic poets, too, became highly concerned with the nature of beauty, with John Keats arguing in Ode on a Grecian Urn that:

- Beauty is truth, truth beauty, —that is all

- Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

Romantic period

In the Romantic period, Edmund Burke postulated a difference between beauty in its classical meaning and the sublime. The concept of the sublime, as explicated by Burke and Kant, suggested viewing Gothic art and architecture, though not in accordance with the classical standard of beauty, as sublime.[10]

20th century and after

The 20th century saw an increasing rejection of beauty by artists and philosophers alike, culminating in postmodernism's anti-aesthetics.[11] This is despite beauty being a central concern of one of postmodernism's main influences, Friedrich Nietzsche, who argued that the Will to Power was the Will to Beauty.[12]

In the aftermath of postmodernism's rejection of beauty, thinkers have returned to beauty as an important value. American analytic philosopher Guy Sircello proposed his New Theory of Beauty as an effort to reaffirm the status of beauty as an important philosophical concept.[13][14] Elaine Scarry also argues that beauty is related to justice.[15]

Beauty is also studied by psychologists and neuroscientists in the field of experimental aesthetics and neuroesthetics respectively. Psychological theories see beauty as a form of pleasure.[16][17] Correlational findings support the view that more beautiful objects are also more pleasing.[18][19][20] Some studies suggest that higher experienced beauty is associated with activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex.[21][22] This approach of localizing the processing of beauty in one brain region has received criticism within the field.[23]

Human beauty

The characterization of a person as “beautiful”, whether on an individual basis or by community consensus, is often based on some combination of inner beauty, which includes psychological factors such as personality, intelligence, grace, politeness, charisma, integrity, congruence and elegance, and outer beauty (i.e. physical attractiveness) which includes physical attributes which are valued on an aesthetic basis.

Standards of beauty have changed over time, based on changing cultural values. Historically, paintings show a wide range of different standards for beauty. However, humans who are relatively young, with smooth skin, well-proportioned bodies, and regular features, have traditionally been considered the most beautiful throughout history.

A strong indicator of physical beauty is "averageness".[24][25][26][27][28] When images of human faces are averaged together to form a composite image, they become progressively closer to the "ideal" image and are perceived as more attractive. This was first noticed in 1883, when Francis Galton overlaid photographic composite images of the faces of vegetarians and criminals to see if there was a typical facial appearance for each. When doing this, he noticed that the composite images were more attractive compared to any of the individual images.[29] Researchers have replicated the result under more controlled conditions and found that the computer-generated, mathematical average of a series of faces is rated more favorably than individual faces.[30] It is argued that it is evolutionarily advantageous that sexual creatures are attracted to mates who possess predominantly common or average features, because it suggests the absence of genetic or acquired defects.[24][31][32][33] There is also evidence that a preference for beautiful faces emerges early in infancy, and is probably innate,[34][35][25][36][37] and that the rules by which attractiveness is established are similar across different genders and cultures.[38][39]

A feature of beautiful women that has been explored by researchers is a waist–hip ratio of approximately 0.70. Physiologists have shown that women with hourglass figures are more fertile than other women due to higher levels of certain female hormones, a fact that may subconsciously condition males choosing mates.[40][41] However, other commentators have suggested that this preference may not be universal. For instance, in some non-Western cultures in which women have to do work such as finding food, men tend to have preferences for higher waist-hip ratios.[42][43][44]

Beauty standards are rooted in cultural norms crafted by societies and media over centuries. Globally, it is argued that the predominance of white women featured in movies and advertising leads to a Eurocentric concept of beauty, breeding cultures that assign inferiority to women of color.[45] Thus, societies and cultures across the globe struggle to diminish the longstanding internalized racism.[46] The black is beautiful cultural movement sought to dispel this notion in the 1960s.[47]

Exposure to the thin ideal in mass media, such as fashion magazines, directly correlates with body dissatisfaction, low self-esteem, and the development of eating disorders among female viewers.[48][49] Further, the widening gap between individual body sizes and societal ideals continues to breed anxiety among young girls as they grow, highlighting the dangerous nature of beauty standards in society.[50]

The concept of beauty in men is known as 'bishōnen' in Japan. Bishōnen refers to males with distinctly feminine features, physical characteristics establishing the standard of beauty in Japan and typically exhibited in their pop culture idols. A multibillion-dollar industry of Japanese Aesthetic Salons exists for this reason. However, different nations have varying male beauty ideals; Eurocentric standards for men include tallness, leanness, and muscularity; thus, these features are idolized through American media, such as in Hollywood films and magazine covers.[51]

Eurocentrism and beauty

The prevailing eurocentric concept of beauty has varying effects on different cultures. Primarily, adherence to this standard among African American women has bred a lack of positive reification of African beauty, and philosopher Cornel West elaborates that, "much of black self-hatred and self-contempt has to do with the refusal of many black Americans to love their own black bodies-especially their black noses, hips, lips, and hair."[52] These insecurities can be traced back to global idealization of women with light skin, green or blue eyes, and long straight or wavy hair in magazines and media that starkly contrast with the natural features of African women.[53]

In East Asian cultures, familial pressures and cultural norms shape beauty ideals; professor and scholar Stephanie Wong's experimental study concluded that expecting that men in Asian culture didn't like women who look “fragile” impacted the lifestyle, eating, and appearance choices made by Asian American women.[54][55] In addition to the male gaze, media portrayals of Asian women as petite and the portrayal of beautiful women in American media as fair complexioned and slim-figured induce anxiety and depressive symptoms among Asian American women who don't fit either of these beauty ideals.[54][55] Further, the high status associated with fairer skin can be attributed to Asian societal history; upper-class people hired workers to perform outdoor, manual labor, cultivating a visual divide over time between lighter complexioned, wealthier families and sun tanned, darker laborers.[55] This along with the Eurocentric beauty ideals embedded in Asian culture has made skin lightening creams, rhinoplasty, and blepharoplasty (an eyelid surgery meant to give Asians a more European, "double-eyelid" appearance) commonplace among Asian women, illuminating the insecurity that results from cultural beauty standards.[55]

Western ideals in beauty and body type

Much criticism has been directed at models of beauty which depend solely upon Western ideals of beauty as seen for example in the Barbie model franchise. Criticisms of Barbie are often centered around concerns that children consider Barbie a role model of beauty and will attempt to emulate her. One of the most common criticisms of Barbie is that she promotes an unrealistic idea of body image for a young woman, leading to a risk that girls who attempt to emulate her will become anorexic.[56]

These criticisms have led to a constructive dialogue to enhance the presence of non-exclusive models of Western ideals in body type and beauty. Complaints also point to a lack of diversity in such franchises as the Barbie model of beauty in Western culture.[57] Mattel responded to these criticisms. Starting in 1980, it produced Hispanic dolls, and later came models from across the globe. For example, in 2007, it introduced "Cinco de Mayo Barbie" wearing a ruffled red, white, and green dress (echoing the Mexican flag). Hispanic magazine reports that:

[O]ne of the most dramatic developments in Barbie's history came when she embraced multi-culturalism and was released in a wide variety of native costumes, hair colors and skin tones to more closely resemble the girls who idolized her. Among these were Cinco De Mayo Barbie, Spanish Barbie, Peruvian Barbie, Mexican Barbie and Puerto Rican Barbie. She also has had close Hispanic friends, such as Teresa.[58]

Effects on society

Researchers have found that good-looking students get higher grades from their teachers than students with an ordinary appearance.[59] Some studies using mock criminal trials have shown that physically attractive "defendants" are less likely to be convicted—and if convicted are likely to receive lighter sentences—than less attractive ones (although the opposite effect was observed when the alleged crime was swindling, perhaps because jurors perceived the defendant's attractiveness as facilitating the crime).[60] Studies among teens and young adults, such as those of psychiatrist and self-help author Eva Ritvo show that skin conditions have a profound effect on social behavior and opportunity.[61]

How much money a person earns may also be influenced by physical beauty. One study found that people low in physical attractiveness earn 5 to 10 percent less than ordinary-looking people, who in turn earn 3 to 8 percent less than those who are considered good-looking.[62] In the market for loans, the least attractive people are less likely to get approvals, although they are less likely to default. In the marriage market, women's looks are at a premium, but men's looks do not matter much.[63]

Conversely, being very unattractive increases the individual's propensity for criminal activity for a number of crimes ranging from burglary to theft to selling illicit drugs.[64]

Discrimination against others based on their appearance is known as lookism.[65]

Writers' definitions

St. Augustine said of beauty "Beauty is indeed a good gift of God; but that the good may not think it a great good, God dispenses it even to the wicked."[66]

Philosopher and novelist Umberto Eco wrote On Beauty: A History of a Western Idea (2004)[67] and On Ugliness (2007).[68] A character in his novel The Name of the Rose declares: "three things concur in creating beauty: first of all integrity or perfection, and for this reason we consider ugly all incomplete things; then proper proportion or consonance; and finally clarity and light", before going on to say "the sight of the beautiful implies peace".[69]

See also

References

- Gary Martin (2007). "Beauty is in the eye of the beholder". The Phrase Finder. Archived from the original on November 30, 2007. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- Konstan, David (2014). Beauty - The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 30–35. ISBN 978-0-19-992726-5.

- Matthew 23:27, Acts 3:10, Flavius Josephus, 12.65

- Euripides, Alcestis 515.

- Seife, Charles (2000). Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea. Penguin. p. 32. ISBN 0-14-029647-6.

- Phaedrus

- Nicomachean Ethics

- Summa Theologica, Part 1, Question 39, Article 8

- Francis Hutcheson (1726). An Inquiry Into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue: In Two Treatises. J. Darby.

- Edmund Burke (1787). A philosophical enquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful. Dodsley.

- Hal Foster (1998). The Anti-aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. New Press. ISBN 978-1-56584-462-9.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1967). The Will To Power. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-70437-1.

- A New Theory of Beauty. Princeton Essays on the Arts, 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975.

- Love and Beauty. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Elaine Scarry (November 4, 2001). On Beauty and Being Just. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08959-0.

- Reber, Rolf; Schwarz, Norbert; Winkielman, Piotr (2004). "Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: is beauty in the perceiver's processing experience?". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 8 (4): 364–382. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_3. hdl:1956/594. ISSN 1088-8683. PMID 15582859.

- Armstrong, Thomas; Detweiler-Bedell, Brian (December 2008). "Beauty as an emotion: The exhilarating prospect of mastering a challenging world". Review of General Psychology. 12 (4): 305–329. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.406.1825. doi:10.1037/a0012558. ISSN 1939-1552.

- Vartanian, Oshin; Navarrete, Gorka; Chatterjee, Anjan; Fich, Lars Brorson; Leder, Helmut; Modroño, Cristián; Nadal, Marcos; Rostrup, Nicolai; Skov, Martin (June 18, 2013). "Impact of contour on aesthetic judgments and approach-avoidance decisions in architecture". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (Supplement 2): 10446–10453. doi:10.1073/pnas.1301227110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3690611. PMID 23754408.

- Marin, Manuela M.; Lampatz, Allegra; Wandl, Michaela; Leder, Helmut (November 4, 2016). "Berlyne Revisited: Evidence for the Multifaceted Nature of Hedonic Tone in the Appreciation of Paintings and Music". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 10: 536. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00536. ISSN 1662-5161. PMC 5095118. PMID 27867350.

- Brielmann, Aenne A.; Pelli, Denis G. (May 22, 2017). "Beauty Requires Thought". Current Biology. 27 (10): 1506–1513.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.018. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 6778408. PMID 28502660.

- Kawabata, Hideaki; Zeki, Semir (April 2004). "Neural correlates of beauty". Journal of Neurophysiology. 91 (4): 1699–1705. doi:10.1152/jn.00696.2003. ISSN 0022-3077. PMID 15010496.

- Ishizu, Tomohiro; Zeki, Semir (July 6, 2011). "Toward A Brain-Based Theory of Beauty". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e21852. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621852I. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021852. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3130765. PMID 21755004.

- Conway, Bevil R.; Rehding, Alexander (March 19, 2013). "Neuroaesthetics and the Trouble with Beauty". PLOS Biology. 11 (3): e1001504. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001504. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 3601993. PMID 23526878.

- Langlois, Judith H.; Roggman, Lori A. (1990). "Attractive Faces Are Only Average". Psychological Science. 1 (2): 115–121. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1990.tb00079.x.

- Strauss, Mark S. (1979). "Abstraction of prototypical information by adults and 10-month-old infants". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory. American Psychological Association (APA). 5 (6): 618–632. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.5.6.618. ISSN 0096-1515. PMID 528918.

- Rhodes, Gillian; Tremewan, Tanya (1996). "Averageness, Exaggeration, and Facial Attractiveness". Psychological Science. SAGE Publications. 7 (2): 105–110. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00338.x. ISSN 0956-7976.

- Valentine, Tim; Darling, Stephen; Donnelly, Mary (2004). "Why are average faces attractive? The effect of view and averageness on the attractiveness of female faces". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 11 (3): 482–487. doi:10.3758/bf03196599. ISSN 1069-9384. PMID 15376799.

- "Langlois Social Development Lab – The University of Texas at Austin". homepage.psy.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- Galton, Francis (1879). "Composite Portraits, Made by Combining Those of Many Different Persons Into a Single Resultant Figure". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. JSTOR. 8: 132–144. doi:10.2307/2841021. ISSN 0959-5295. JSTOR 2841021.

- Langlois, Judith H.; Roggman, Lori A.; Musselman, Lisa (1994). "What Is Average and What Is Not Average About Attractive Faces?". Psychological Science. SAGE Publications. 5 (4): 214–220. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1994.tb00503.x. ISSN 0956-7976.

- Koeslag, Johan H. (1990). "Koinophilia groups sexual creatures into species, promotes stasis, and stabilizes social behaviour". Journal of Theoretical Biology. Elsevier BV. 144 (1): 15–35. doi:10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80297-8. ISSN 0022-5193. PMID 2200930.

- Symons, D. (1979) The Evolution of Human Sexuality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Highfield, Roger (May 7, 2008). "Why beauty is an advert for good genes". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- Slater, Alan; Von der Schulenburg, Charlotte; Brown, Elizabeth; Badenoch, Marion; Butterworth, George; Parsons, Sonia; Samuels, Curtis (1998). "Newborn infants prefer attractive faces". Infant Behavior and Development. Elsevier BV. 21 (2): 345–354. doi:10.1016/s0163-6383(98)90011-x. ISSN 0163-6383.

- Kramer, Steve; Zebrowitz, Leslie; Giovanni, Jean Paul San; Sherak, Barbara (February 21, 2019). "Infants' Preferences for Attractiveness and Babyfaceness". Studies in Perception and Action III. Routledge. pp. 389–392. doi:10.4324/9781315789361-103. ISBN 978-1-315-78936-1.

- Rubenstein, Adam J.; Kalakanis, Lisa; Langlois, Judith H. (1999). "Infant preferences for attractive faces: A cognitive explanation". Developmental Psychology. American Psychological Association (APA). 35 (3): 848–855. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.3.848. ISSN 1939-0599. PMID 10380874.

- Langlois, Judith H.; Ritter, Jean M.; Roggman, Lori A.; Vaughn, Lesley S. (1991). "Facial diversity and infant preferences for attractive faces". Developmental Psychology. American Psychological Association (APA). 27 (1): 79–84. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.79. ISSN 1939-0599.

- Apicella, Coren L; Little, Anthony C; Marlowe, Frank W (2007). "Facial Averageness and Attractiveness in an Isolated Population of Hunter-Gatherers". Perception. SAGE Publications. 36 (12): 1813–1820. doi:10.1068/p5601. ISSN 0301-0066. PMID 18283931.

- Rhodes, Gillian (2006). "The Evolutionary Psychology of Facial Beauty". Annual Review of Psychology. Annual Reviews. 57 (1): 199–226. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190208. ISSN 0066-4308. PMID 16318594.

- "Hourglass figure fertility link". BBC News. May 4, 2004. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- Bhattacharya, Shaoni (May 5, 2004). "Barbie-shaped women more fertile". New Scientist. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- "Best Female Figure Not an Hourglass". Live Science. December 3, 2008. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- Locke, Susannah (June 22, 2014). "Did evolution really make men prefer women with hourglass figures?". Vox. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- Begley, Sharon. "Hourglass Figures: We Take It All Back". Sharon Begley. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- Harper, Kathryn; Choma, Becky L. (October 5, 2018). "Internalised White Ideal, Skin Tone Surveillance, and Hair Surveillance Predict Skin and Hair Dissatisfaction and Skin Bleaching among African American and Indian Women". Sex Roles. 80 (11–12): 735–744. doi:10.1007/s11199-018-0966-9. ISSN 0360-0025.

- Weedon, Chris (December 6, 2007). "Key Issues in Postcolonial Feminism: A Western Perspective". Gender Forum Electronic Journal.

- DoCarmo, Stephen. "Notes on the Black Cultural Movement". Bucks County Community College. Archived from the original on April 8, 2005. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- "Media & Eating Disorders". National Eating Disorders Association. October 5, 2017. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "Model's link to teenage anorexia". BBC News. May 30, 2000.

- Jade, Deanne. "National Centre for Eating Disorders - The Media & Eating Disorders". National Centre for Eating Disorders. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "The New (And Impossible) Standards of Male Beauty". Paging Dr. NerdLove. January 26, 2015. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- West, Cornel (1994). Race Matters. Vintage.

- https://search.proquest.com/docview/233235409/

- Wong, Stephanie N.; Keum, Brian TaeHyuk; Caffarel, Daniel; Srinivasan, Ranjana; Morshedian, Negar; Capodilupo, Christina M.; Brewster, Melanie E. (December 2017). "Exploring the conceptualization of body image for Asian American women". Asian American Journal of Psychology. 8 (4): 296–307. doi:10.1037/aap0000077. ISSN 1948-1993. S2CID 151560804.

- Le, C.N (June 4, 2014). "The Homogenization of Asian Beauty - The Society Pages". thesocietypages.org. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- Dittmar, Helga; Halliwell, Emma; Ive, Suzanne (2006). "Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5- to 8-year-old girls". Developmental Psychology. American Psychological Association (APA). 42 (2): 283–292. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.283. ISSN 1939-0599. PMID 16569167.

- Marco Tosa (1998). Barbie: Four Decades of Fashion, Fantasy, and Fun. H.N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-4008-6.

- "A Barbie for Everyone". Hispanic. 22 (1). February–March 2009.

- Sharon Begley (July 14, 2009). "The Link Between Beauty and Grades". Newsweek. Archived from the original on April 20, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- Amina A Memon; Aldert Vrij; Ray Bull (October 31, 2003). Psychology and Law: Truthfulness, Accuracy and Credibility. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-470-86835-5.

- "Image survey reveals "perception is reality" when it comes to teenagers". multivu.prnewswire.com. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- Lorenz, K. (2005). "Do pretty people earn more?". CNN News. Time Warner. Cable News Network.

- Daniel Hamermesh; Stephen J. Dubner (January 30, 2014). "Reasons to not be ugly: full transcript". Freakonomics. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- Erdal Tekin; Stephen J. Dubner (January 30, 2014). "Reasons to not be ugly: full transcript". Freakonomics. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- Leo Gough (June 29, 2011). C. Northcote Parkinson's Parkinson's Law: A modern-day interpretation of a management classic. Infinite Ideas. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-908189-71-4.

- "NPNF1-02. St. Augustine's City of God and Christian Doctrine - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- Eco, Umberto (2004). On Beauty: A historyof a western idea. London: Secker & Warburg. ISBN 978-0436205170.

- Eco, Umberto (2007). On Ugliness. London: Harvill Secker. ISBN 9781846551222.

- Eco, Umberto (1980). The Name of the Rose. London: Vintage. p. 65. ISBN 9780099466031.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beauty. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Beauty |

| Look up beauty or pretty in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Sartwell, Crispin. "Beauty". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Beauty at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- BBC Radio 4's In Our Time programme on Beauty (requires RealAudio)

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Theories of Beauty to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

- beautycheck.de/english Regensburg University – Characteristics of beautiful faces

- Eli Siegel's "Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?"

- Art and love in Renaissance Italy , Issued in connection with an exhibition held Nov. 11, 2008-Feb. 16, 2009, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (see Belle: Picturing Beautiful Women; pages 246-254).