Ringhals Nuclear Power Plant

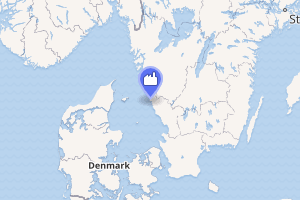

Ringhals is a nuclear power plant in Sweden. It is situated on the Värö Peninsula (Swedish: Väröhalvön) in Varberg Municipality approximately 65 km south of Gothenburg. With a total power rating of 3,055 MWe, it is the largest power plant in Sweden and generates 23 TWh of electricity a year, the equivalent of 15% of the electrical power usage of Sweden. It is owned 70% by Vattenfall and 30% by Uniper SE.

| Ringhals Nuclear Power Plant | |

|---|---|

Ringhals NPP | |

| |

| Country | Sweden |

| Coordinates | 57°15′35″N 12°6′39″E |

| Construction began | 1969 |

| Commission date | R1: 1 January 1976 R2: 1 May 1975 R3: 9 September 1981 R4: 21 November 1983 |

| Decommission date | R2: 30 December 2019 |

| Operator(s) | Ringhals AB (Vattenfall 70.4%, Sydkraft Nuclear 29.6%) |

| Power generation | |

| Units operational | R1: 865 MW R3: 1070 MW R4: 1120 MW |

| Capacity factor | 67% |

| Annual net output | 23 TWh (average 2012-2016) |

| External links | |

| Website | www |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

The plant has three operating reactors: one boiling water reactor (R1) and two pressurized water reactors (R3 and R4). A third pressurized water reactor, R2, was permanently shut down in 2019.

History

Planning and construction, 1965-1983

Planning and land procurement of the site started in 1965. Two reactors were ordered in 1968: one boiling water reactor from ABB-ATOM (R1) and one pressurized water reactor from Westinghouse (R2). Construction work started in 1969; commercial operation started for R2 in 1975, and for R1 in 1976.

Two more pressurized water reactors, R3 and R4, were ordered from Westinghouse in 1971 and construction work started in 1972.

So far the public and political opinion in Sweden was fairly positive to nuclear power. One reason was that until 1970 nearly all electricity came from a continuously increasing exploitation of the large and wild rivers in the north of Sweden, and the diminishing number of remaining, unexploited rivers created fierce opposition against further hydro power development.

Opinion changed and in the parliamentary election of 1976 a new government was elected with a clear mandate to phase out nuclear power no later than 1985. Formally this was imposed through a new law, Villkorslagen which required proof of an "absolute safe" method for disposal of spent nuclear fuel before new reactors were allowed to be loaded with fresh nuclear fuel. The law went into force in spring 1977 and hindered the recently completed unit R3 from being loaded with nuclear fuel. The Swedish nuclear industry then developed a concept for disposal of high-level radioactive waste called KBS-1, later further developed to KBS-3.

Based upon the KBS-1 concept R3 was, through a highly controversial process including a governmental crisis, granted permission to load fuel on 27 March 1979. The Three Mile Island accident occurred the following day which triggered a referendum in Sweden about nuclear power. The referendum was held on 23 March 1980 and the result was interpreted as a "yes" to completion of construction and operation of the whole Swedish nuclear program with 12 reactors. Hence R3 could be loaded with fuel and started commercial operation on 9 September 1981, more than four years after essentially completed the construction phase in 1977.

R4 was also somewhat delayed due to the referendum but also due to remediation of some technical problems identified at the start-up of the sister-plant R3, and started commercial operation 21 November 1983.

Major modifications and upgrades

As a result of the Three Mile Island accident in 1979, all Swedish reactors were required to install FCVS - Filtered Containment Venting System - and ICSS - Independent Containment Spray System. In case of an accident with core degradation and loss of all cooling systems the ICSS can still limit the containment pressure, and should this fail the FCVS can relieve the containment pressure with limited releases of radioactivity. The systems went into operation at Barsebäck 1985 and for the other plants 1989.

As a result of the Barsebäck strainer incident in 1992[1] the recirculation strainer capacity was significantly increased for R1 in 1992 and R2 in 1994. Units R3 and R4 made similar upgrades in 2005.

During the 2005-2015 period, significant improvements were made regarding fire separation, redundancy and diversification of various safety systems, particularly for the older plants R1 and R2 .

The original steam generators for the Ringhals PWRs had tubes of Inconel-600 and details in the construction that made them prone to cracks and corrosion. This triggered huge efforts for inspection, maintenance and repair. Although designed for 40 years of operation, both unit R2 and R3 replaced their steam generators after 14 years, i.e. 1989 and 1995. Unit R4, starting later, could take advantage of being aware of the problems, and due to high attention to water chemistry and maintenance efforts the R4 steam generators were replaced in 2011 after 28 years of operation. All the new steam generators have tubes of Inconel-690 and improved design, and have had very few problems and high availability. This is especially true for R2 which, as of 2017, had been operating 28 years with the new steam generators.

As a result of analysis and observations from the Three Mile Island accident, the Ringhals PWR reactors installed PAR - Passive Autocatalytic hydrogen Recombiners in 2007. Each reactor contains a number of PAR units with catalytic plates, which after a severe core degradation can process the hydrogen emanating from the fuel cladding oxidation within a few hours and hence reduce the risk for violent hydrogen combustion.

All European nuclear power plants including Ringhals had to perform stress-tests after the Fukushima accident 2011, where consequences of certain beyond-design-events should be assessed.[2] The availability of FCVS - Filtered Containment Venting System, ICSS - Independent Containment Spray System and PAR - Passive Autocatalytic hydrogen Recombiners, turned out to be valuable capabilities in these beyond-design-events and no immediate plant modifications were proposed as a post-Fukushima-response. On the contrary Ringhals made significant upgrades in the emergency preparedness organization in the size, education and training of the staffing, and in the independence and durability (power supply, communications, etc) for certain systems and buildings.

In December 2014, the Swedish regulator required that all Swedish reactors should be equipped with an Independent Core Cooling System - ICCS - before 31 December 2020.[3] The system should be able to cool the reactor during 72 hours without any supply of water, power, fuel or other consumables, and should survive external events (seismic events, hard weather etc) with an estimated probability of exceedance of 10−6/yr. The requirements are influenced by the so called "Forsmark-event" 25 July 2006 and the Fukushima accident. Design of and preparations for ICCS is (2017) already underway for R3 and R4, but will not be made for R1 and R2 since they will be shut down before 2021.[4]

Incidents

Following a number of observations of deficiencies in the safety culture since 2005, the Swedish Radiation Safety Authority decided in 2009 to put Ringhals under increased surveillance.[5] Ringhals made certain efforts in order to improve traceability and transparency in decision making, internal audits and analyses of incidents and mistakes. The regulator acknowledged the improvements, and the increased surveillance was waived for 2013.[6]

In 2012 a small quantity of explosives, although without any firing device, was found during a routine check underneath a truck at the plant.[7] For a short time all nuclear power plants in Sweden increased their alert level, but no more explosives were found, and no-one could be tied to the discovery.

In October 2012, 20 anti-nuclear Greenpeace activists scaled the outer perimeter standard industrial fence, and there was also an incursion at Forsmark nuclear power plant. Greenpeace said that its non-violent actions were "intended to protest against the continuing operation of these reactors, which it argues were shown to be unsafe in European stress tests."[8] The inner perimeter fence (with barbered wire, CCTV-surveillance, "no-go" zone etc) around the reactors was not scaled.[9]

On 30 July 2018, Ringhals-2 was taken offline during the 2018 European heat wave, since the sea water temperature exceeded the design limit 25 DegC. The reactor was restarted on 3 August.[10] The other reactors R1, R3 and R4 were not affected since they are licensed for slightly higher temperatures.

Plans for operation and decommissioning

In October 2015, Vattenfall decided to close down Ringhals 1 by 2020 and Ringhals 2 by 2019 due to their declining profitability, instead of, as previously announced, around 2025.[11][4] Ringhals 3 and 4 are still expected to continue in service until the 2040s.[12]

In January 2016, Vattenfall announced that all its Swedish nuclear power plants, including the newer reactors, were operating at a loss due to low electricity prices and Sweden's nuclear power tax ("effektskatt"). It warned that it may be forced to shut all the nuclear plants down, and argued that the nuclear output tax, which constituted over one third of the price,[13] should be scrapped.[14] Through an agreement 10 June 2016[15] the major part of the nuclear power tax was removed on 1 July 2017, but combined with prolonged and enhanced support for renewable electricity production. The removal of the nuclear power tax corresponds to a tax reduction of approximately 7 öre or 0.007 EUR/kWh which corresponds to around 25% of the generating cost. This is a significant cost reduction and has been important for Vattenfall's decision to operate R3 and R4 until the 2040s.

On 20 December 2019, the R2 reactor was permanently shut down[16].

On June 2020, a contract was signed between Svenska kraftnät and Ringhals AB that would grant Ringhals an allowance of 300 million SEK (approximately 30 million US dollars) to keep R1 reactor open from 1st of July to 15th September 2020 in order to fuel the increasing demand for electricity.[17]

References

- "Information Notice No. 92-71: Partial Plugging of Suppression Pool Strainers at a Foreign BWR". NRC - United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission. 30 September 1992. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- "R1-R4 ENSREG Stress Test - Summary (Ringhals document)" (PDF). SSM - Strålsäkerhetsmyndigheten - Swedish Radiation Safety Authority. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- "Villkor för oberoende härdkylning för Ringhals 3 (Requirements for independent core cooling for Ringhals 3) (Nearly identical requirements for other Swedish reactors)" (PDF). Strålsäkerhetsmyndigheten SSM (Swedish Radiation Safety Authority. 15 December 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- "Upgrade allows continued operation of Ringhals units". World Nuclear News. 17 November 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- "Pressmeddelande: SSM beslutar om särskilda villkor för drift vid Ringhals" (in Swedish). Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Ringhals: myndigheten upphäver särskild tillsyn (Ringhals: The Regulator waives increased surveillance)". Strålsäkerhetsmyndigheten (Swedish Radiation Safety Authority). 11 June 2013.

- "Explosives found at Sweden nuclear site in Ringhals". BBC. 21 June 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "The antis attack!". Nuclear Engineering International. 5 April 2013.

- "Greenpeace cyklade in på Ringhals (Greenpeace entered Ringhals by bike)". SvT - Swedish public service television. 9 October 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- "Sweden's Ringhals-2 nuclear reactor offline due to high water temperature". Reuters. 2018.

- "Ringhals 2 stängs redan 2019 (Ringhals 2 will close already 2019)". Svt nyheter (Swedish public service television). 11 October 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- "Sweden to speed up nuclear reactors closure". thelocal.se. 28 April 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- Riksdagsförvaltningen. "Lag (2000:466) om skatt på termisk effekt i kärnkraftsreaktorer Svensk författningssamling 2000:2000:466 t.o.m. SFS 2017:401 - Riksdagen". www.riksdagen.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "Vattenfall seeks to return reactors to profitability". World Nuclear News. 8 January 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- "Energiöverenskommelsen 2016-06-10 (the agreement about energy in Sweden 2016-06-10)" (PDF). Regeringen (The Swedish Government. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- "Ringhals reaktor 2 stänger efter 44 år" [Ringhals reactor 2 closes after 44 years]. Expressen (in Swedish). 30 December 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- https://www.nyteknik.se/premium/unikt-avtal-reaktor-sakrar-elnatet-i-sommar-6997676. Unknown parameter

|rubrik=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|datum=ignored (|date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|tidning=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|författare=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help)