Nuclear power in Sweden

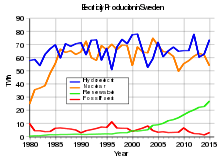

Sweden has three operational nuclear power plants with 7 operational nuclear reactors, which produce about 40% of the country's electricity.[1] The nation's largest power station, Ringhals Nuclear Power Plant, has four reactors and generates about 15 percent of Sweden's annual electricity consumption.[2]

Sweden formerly had a nuclear phase-out policy, aiming to end nuclear power generation in Sweden by 2010. On 5 February 2009, the Government of Sweden announced an agreement allowing for the replacement of existing reactors, effectively ending the phase-out policy.[3]

History

Sweden began research into nuclear energy in 1947 with the establishment of the Atomic Energy Company, which originated in the ongoing military research and development at the Defence Institute FOA.[4] In 1954, the country built its first small research heavy water reactor. It was followed by two heavy water reactors: Ågesta, a small heat and power reactor in 1964, and Marviken which was finished but never operated, due to several safety issues.[5]

On 1 May 1969, the prototype nuclear cogeneration plant Ågestaverket (R3) suffered an incident in which secondary cooling water flooded through a broken valve and caused a number of electrical problems in the plant, resulting in a 4-day shutdown.[6]

R1, R3, and particularly the never finished R4 project at Marviken were heavy water reactors, motivated by the option to use Swedish uranium without isotope enrichment and by the possibility to use the reactors to produce weapons grade plutonium for Swedish nuclear warheads. The Swedish nuclear weapons program was eventually shut down, however, and Sweden signed the nuclear non-proliferation treaty in 1968.[7]

Six nuclear reactors began commercial service in the 1970s, another six through 1985. Nine of the reactors were designed by Allmänna Svenska Elektriska Aktiebolaget (ASEA), three supplied by Westinghouse.

After the Three Mile Island accident in 1979, there was a national referendum in Sweden about the future of nuclear power. As a result of this, the Riksdag decided in 1980 that no further nuclear power plants should be built, and that a nuclear power phase-out should be completed by 2010. Some observers have condemned the referendum as flawed because people could only vote "NO to nuclear", although three options were basically a harder or a softer "NO".[8][9]

After the 1986 Chernobyl accident in USSR, the question of security of nuclear energy was again raised. In July 1992 an incident at Barsebäck 2 showed that the five older boiling water reactors had had potentially reduced capacity in their emergency core cooling systems since they started operation. Mineral wool was dislodged and ended up in the suppression pool where it clogged the suction strainers.[10] It was classified as a grade 2 incident in the IAEA INES scale, due to the degradation of defence-in-depth. All five reactors were ordered down by the Nuclear Inspectorate for remedial action where backwash and additional strainers were installed. Most of the reactors were back in operation by next Spring, but Oskarshamn 1 remained down until January 1996 due to other work being carried out.

During the late 1990s a unique capacity tax on nuclear power (effektskatten) was introduced. It was initially set at 5514 SEK per MWth per month, and only applied to nuclear power plants, thus penalizing them relative to other energy sources. In January 2006 it was almost doubled (at 10,200 SEK per MWth per month).[11] An agreement struck in June 2016 among other things meant the capacity tax would be phased out by 2019. By then the tax constituted about one third of the cost of operating a nuclear reactor.[12]

In 1997 the Riksdag decided to shut down one of the reactors at Barsebäck by 1 July 1998 and the second before 1 July 2001, although under the condition that their energy production would be compensated.[13] The next conservative government tried to cancel the phase-out, but, after protests, decided instead to extend the time limit to 2010. At Barsebäck, block 1 was shut down on 30 November 1999 and block 2 on 1 June 2005.

In August 2006 three of Sweden's ten nuclear reactors were shut down due to safety concerns following an incident at Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant, in which two out of four emergency power generators failed causing a power shortage. It was classified as a grade 2 incident in the INES scale, due to the degradation of defence-in-depth.

In 2006 the Centre Party of Sweden, an opposition party that supported the phase-out, announced that it was dropping its opposition to nuclear power, at least for the time being, claiming that it is unrealistic to expect the phase-out in the short term. It said it would now support the stance of the other opposition parties in Alliance for Sweden, which were considerably more pro-nuclear than the then Social Democratic government.[14]

On 17 June 2010, the Riksdag adopted a decision allowing the replacement of the existing reactors with new nuclear reactors, starting from 1 January 2011.[15]

On 30 December 2019, Ringhals reactor 2 was shut down.[16]

List of reactors

| Name | Unit No. |

Reactor | Status | Capacity in MW | Construction start | Commercial operation | Closure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Model | Net | Gross | ||||||

| Ågesta | 1 | PHWR | R3 | Shut down/dismanteled | 10 | 12 | 1 December 1957 | 1 May 1964 | 2 June 1974 |

| Barsebäck | 1 | BWR | ASEA-II | Shut down/in decommissioning | 600 | 615 | 1 February 1971 | 1 July 1975 | 30 November 1999 |

| 2 | BWR | ASEA-II | Shut down/in decommissioning | 600 | 615 | 1 January 1973 | 1 July 1977 | 31 May 2005 | |

| Forsmark | 1 | BWR | ASEA-III, BWR-2500 | Operational | 986 | 1022 | 1 June 1973 | 10 December 1980 | |

| 2 | BWR | ASEA-III, BWR-2500 | Operational | 1116 | 1156 | 1 January 1975 | 7 July 1981 | ||

| 3 | BWR | ASEA-IV, BWR-3000 | Operational | 1167 | 1203 | 1 January 1979 | 18 August 1985 | ||

| Oskarshamn | 1 | BWR | ASEA-I | Shut down/in decommissioning | 473 | 492 | 1 August 1966 | 6 February 1972 | 19 June 2017 |

| 2 | BWR | ASEA-II | Shut down/in decommissioning | 638 | 661 | 1 September 1969 | 1 January 1975 | 22 December 2016 | |

| 3 | BWR | ASEA-III, BWR-3000 | Operational | 1400 | 1450 | 1 May 1980 | 15 August 1985 | ||

| R4 | 1 | Unfinished | 130 | ||||||

| Ringhals | 1 | BWR | ASEA-I | Operational | 881 | 910 | 1 February 1969 | 1 January 1976 | (2020) |

| 2 | PWR | WH 3-loops | Shut down | 904 | 963 | 1 October 1970 | 1 May 1975 | 30 December 2019 | |

| 3 | PWR | WH 3-loops | Operational | 1062 | 1117 | 1 September 1972 | 9 September 1981 | ||

| 4 | PWR | WH 3-loops | Operational | 1104 | 1171 | 1 November 1973 | 21 November 1983 | ||

Public opinion

The nuclear energy phase-out is controversial in Sweden. The energy production of the remaining nuclear power plants has been considerably increased in recent years to compensate for the Barsebäck shut-down.

In May 2005, a poll of residents living around Barsebäck found that 94% wanted it to stay. The subsequent leak of radioactive water from the nuclear waste store in Forsmark did not lead to a major change in public opinion.[17] According to a poll of January 2008, 48% of Swedes were in favour of building new nuclear reactors, 39% were opposed and 13% were undecided. However, the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan reversed prior support of nuclear power, with polls showing that 64% of Swedes opposed new reactors while 27% supported them.[18] However, in a poll November 2019 the public opinion has changed with 78 % in favor of nuclear power and only 11 % against. [19]

Prior public support for nuclear power stood in contrast to the stances of the major political parties in Sweden, but after the polls in late 2019 the debate changed and the parties that wants to build new nuclear power in Sweden (SD, M, KD, L ) put forth a demand to the leading government party, the Social Democrats to chose a path forward, otherwise they might break with the standing energy agreement and work to reform the policy towards nuclear power, outside of the influence of the minority government.[20]

Nuclear waste

Sweden has a well-developed nuclear waste management policy. Low-level waste is currently stored at the reactor sites or destroyed at Studsvik. The country has dedicated a ship, M/S Sigyn, to move waste from power plants to repositories. Sweden has also constructed a permanent underground repository, SFR, final repository for short-lived radioactive waste, with a capacity of 63,000 cubic meters for intermediate and low-level waste. A central interim storage facility for spent nuclear fuel, Clab, is located near Oskarshamn. The government has also identified two potential candidates for burial of additional waste (high-level), Oskarshamn and Östhammar.[21]

Anti-nuclear activists

In June 2010, Greenpeace anti-nuclear activists invaded Forsmark nuclear power plant to protest the then-plan to remove the government prohibition on building new nuclear power plants. In October 2012, 20 Greenpeace activists scaled the outer perimeter fence of the Ringhals nuclear plant, and there was also an incursion of 50 activists at the Forsmark plant. Greenpeace said that its non-violent actions were protests against the continuing operation of these reactors, which it says are unsafe in European stress tests, and to emphasise that stress tests did nothing to prepare against threats from outside the plant. A report by the Swedish nuclear regulator said that "the current overall level of protection against sabotage is insufficient". Although Swedish nuclear power plants have security guards, the police are responsible for emergency response. The report criticised the level of cooperation between nuclear site staff and police in the case of sabotage or attack.[22]

Photo gallery

The Barsebäck Nuclear Power Plant, which has been shut down

The Barsebäck Nuclear Power Plant, which has been shut down

References

- http://pris.iaea.org/public/, see Sweden

- Vattenfall - QuickLink

- Borgenäs, Johan (November 11, 2009). "Sweden Reverses Nuclear Phase-out Policy". Nuclear Threat Initiative.

- T. Jonter: Nuclear Weapon Research in Sweden. The Co-operation Between Civilian and Military Research, 1947-1972, SKI Report 02:18

- Jonter ibid

- The Flooding Incident at the Ågesta Pressurized Heavy Water Nuclear Power Plant (pdf)

- "Neutral Sweden Quietly Keeps Nuclear Option Open", The Washington Post, 25 November 1994

- Nils-Olov Jonsson and Carl Berglöf (2016). "Nuclear Power Plants in Sweden during the Last 40 Years". European Nuclear Society. Archived from the original on 2018-10-02. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- E. Denton (Jr.), Robert (2000). Political Communication Ethics: An Oxymoron?. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 159. ISBN 9780275964832.

- https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/gen-comm/bulletins/1996/bl96003.html

- http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-o-s/sweden.aspx

- "Sweden strikes deal to continue nuclear power". The Local. 10 June 2016.

- M. Griffin, James (2003). Global Climate Change: The Science, Economics and Politics. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 238. ISBN 9781843767138.

- Centre dumps nuclear deal Archived 2008-03-02 at the Wayback Machine, The Local, 30 May 2006

- "New phase for Swedish nuclear". World Nuclear News. 18 June 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- "Ringhals 2 nuclear plant shuts down". Vattenfall. 19 December 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Vindkraftverk möter största motståndet i Skåne Archived 2005-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, Sydsvenskan, 15 August 2005

- Swedes oppose new nuclear power: poll, The Local, 19 March 2011

- Rekordfå är emot kärnkraft i Sverige, NyTeknik, 22 November 2019

- Tar strid för mer kärnkraft – kräver att S väljer väg, Aftonbladet, 29 October 2019

- "Nuclear Energy in Sweden". World Nuclear Association. April 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "The antis attack!". Nuclear Engineering International. 5 April 2013.

Further reading

- William D. Nordhaus, The Swedish Nuclear Dilemma — Energy and the Environment, 1997 Hardcover, ISBN 0-915707-84-5.

- Arne Kaijser / Jan-Henrik Meyer, “The World´s Worst Located Nuclear Power Plant”: Danish and Swedish perspectives on the Swedish nuclear power plant Barsebäck. Journal for the History of Environment and Society 3 (2018): 71-105. Full Text

- Arne Kaijser, Sweden. Short Country Report (History of Nuclear Energy and Society Project) Update 2018. http://www.honest2020.eu/sites/default/files/deliverables_24/SW.pdf.

External links

- "Nuclear Power in Sweden". Country Briefings. World Nuclear Association (WNA). January 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- News

- 3 August 2006, BBC: Swedes shut down some nuclear reactors following testing failures