Reihengräber culture

The Reihengräber culture (translated from German as Row grave culture) is an archaeological culture that refers to the burial practice of regularly arranged, identically orientated inhumation graves between the mid-fifth and early-eight century in central and western Europe.[1] Existing within the Merovingian sphere of influence, the Reihengräber culture was dominant in modern Belgium, northern France and the Rhineland, and developed from a blending of Gallic and Scandinavian cultures in the late-Roman to early-medieval period. Though the relevance of the Reihengräber culture in outlining the complex ethnic, political and cultural context of 5th-7th century Europe has been questioned, similarities in material culture development within the Reihengräber region outline the existence of Kerngebiet, or core areas of cultural unity and development, within Germanic territories during Merovingian rule.[2]

Geographical context

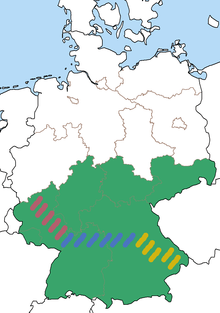

The Reihengräber culture, which developed within north-eastern Gaul under Romano-Germanic settlement during the fifth century, spread to the regions of Germanic regions of Thuringia and Bavaria in the sixth century. Scholars have divided the Reihengräber culture into an eastern “Thuringian and Langobard” zone and a western “Bavarian and Alamanni” zone, based on the similar burial customs and material culture shared between these ethnic groups. Frankish populations were also present within these zones. Most Reihengräber sites are found on the River Danube or the River Main, with pockets of Frankish dominated settlements on the River Rhine. The eastern zone of the Reihengräber culture lies within the Thuringian Forest south of the Harz mountains, and extends eastward towards the River Elbe, where Slavic cultures with settled on the eastern bank. The western Bavarian zone however lies between the River Lech and River Enns. Both zones remained autonomous of Merovingian control until the mid-6th century, when Garibald I of Bavaria was installed as Duke in 555 A.D.[3]

The uniformity of the Reihengräber culture’s burial practices is attributed to Clovis I, who unified the tribes of the Reihengräber region into the early Merovingian dynasty. The unification of the Frankish dominated tribes into a single ‘row grave culture’ was successful in simplifying burial customs from various forms of cremation or ritualised inhumation into this single practice.[4]

Burial practices

The Reihengräber culture features the burial practice of evenly spaced rows. In addition to the placement of funerary objects within the graves, the Reihengräber culture is also known for the burial of horses, which while rare in the Bavarian zone, are common throughout burial sites in Gaul and Thuringia[3]. The reopening of burial mounds and removal of grave goods shortly after burial is also a significant feature of Reihengräber culture burial customs, and is linked culturally to Scandinavian practices associated with object animism. This practice is especially prevalent in the Frankish and Langobard areas of the ‘Reihengräber eastern zone’ and peaks in practice in the early 7th century.[5] This removal of burial objects, known as furta sacra, became especially common during the Carolingian dynasty during the 9th century, and was based off Harald Bluetooth's desecration of aristocratic burial mounds during his campaign in the Viken region[6]. The usage of wetlands as predominant burial sites also runs parallels with Scandinavian practices[5].

Material culture

The material culture of the Reihengräber reveals distinctions between male and female burial practices. Male graves typically contain swords, axes and belts, whereas female graves largely contained brooches, necklaces and girdle hangers[5]. Bronze conical helmets in the Reihengräber culture are also prevalent, and are especially of note as they were offered as funerary objects within the late-iron age[2]. Animistic designs occur extensively throughout Reihengräber material culture, in particular bird-like iconography and shapes of Thuringian bow brooches[3]. Late fifth century Thuringian graves in modern Scherzheim also contained sets of Zierschlusselpaare, or symbolic keys pairs, uncommon artefacts whose ritual significance is yet unknown[2].

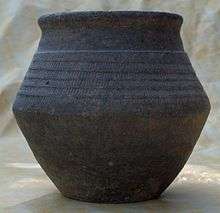

Another common item is the biconical pot, (German: Knickwandtopf, Dutch: Knikwandpot, and French: Vase biconique), the most important type of ceramics from the Merovingian period. The name is derived from the shape of the vessel, the form looking like two cones on top of each other. Often, the outside of the pot is decorated with stamps, impressions or lines. The distribution of the pottery shows that these vases originate from different ceramic production sites. Biconical pots are also found in settlements.[7]

Interpretation

Social status

Disparities in funerary good quality and prevalence between Frankish and other ethnic groups’ graves within the Reihengräber culture also suggest a Frankish overclass who represented local leadership and nobility.[8] The theory that Frankish rulers perceived the Germanic peoples of the Reihengräber as laeti was suggested by Gregory of Tours in his Historia Francorum. Thuringian brooches give evidence to a cultural stratification between an elite and lower class, as they were developed on the commission of nobility and were almost exclusively found within he funerary sites of the entourages and personal attendants to these elites, who were mostly of Frankish descent[3]. Despite clearly demarcated class differences between Frankish and Germanic peoples of the Reihengräber culture, the lower class of both ethnic groups show few differences in burial practices, with the cemetery at Zeuzblen in Schweinfurt revealing burials of both groups side by side in the classic row-graves style. All graves showed burial gifts crafted in the Thuringian make, and reveal that many Frankish commoners integrated the material culture with native Germanic populations in the Reihengräber region[3]

Property rights

During the 1920s, archaeological investigation of the Reihengräber culture led to the understanding the deposited funerary objects were seen as distinctly inalienable property that could not be inherited of sold. The Reihengräber culture identified inalienable property as artefacts that could not be sold or exchanged due to their symbolic role as 'companion' objects to their original creators.[9] These concepts are integral to the Reihengräber culture’s unique burial customs, and were instrumental in establishing the Merovingian concept of male property rights over weaponry in a custom known as hergewaete. Female property rights over household and jewellery, known as gerade, have also been identified. Many of these inalienable property objects were found to have been removed from the graves as matching the Reihengräber style[5]. These concepts of inalienable property rights developed in the Reihengräber region, contains similarities with the tenth century Germanic legal code of Sachsenspiegel, and influenced its creation[8].

Following the Christianisation of Merovingian Gaul, and hence the Reihengräber region, in the early 6th century, these property rights were transferred as Church property upon the owner’s death. Gold foil crosses also begin to appear in the archaeological record of the Reihengräber culture from the late sixth to seventh century, appearing mostly around the French Alps and providing evidence for the Christianisation of the Reihengräber region during this period[3].

Ethnography

The usefulness of the denomination of Frankish, Thuringian, Bavarian and other cultures as Reihengräber culture is debated within the archaeological scholarship. It is clear that these ethnic groups shares similar burial practices, especially considering the increasing prevalence of Frankish arms in connecting the Reihengräber region’s military culture[3]. Particularly, the Francisca battle-axes, developed by Frankish warriors, have been located not just in the Merovingian heartland of Gaul, but also throughout the Reihengräber region in Thuringia, Almannia and Bavaria. These serve as example of both the enforced unification of the Reihengräber region under Clovis’ early Merovingian dynasty, but also as evidence of the adoption of Frankish warcraft in uniting the ethnic groups of the Reihengräber region[3].

However, no single material culture unites the various communities pooled into the Reihengräber culture, as Frankish, Gothic and Thuringian artefact forms exist among many local styles throughout the region[1]. Social mobility within the Merovingian period influenced the sharing of local customs, eventuating in an amalgamation of burial practices that led to the eventually spaced inhumation graves and grave good deposits that dominated the region in the mid-6th century.[10] Ethnic groups seem to have also moved throughout the Reihengräber region constantly with permanent settlement largely matched by military control by dominant ethnic groups. The collapse of the Thuringian kingdoms between 531 and 534 resulted in large populations of Thuringian peoples emigrating from the region into Frankish territories in modern-France, leading to the introduction of Reihengräber burial practices and material culture into western Europe, though they remained a subordinate class to the Frankish overclass[3].

References

- Gräslund, Anne-Sofie. "Birka IV The Burial Customs: a study of the graves on Björkö. Conclusions". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Fahlander, Fredrik. "Making Sense of Things: Archaeologies of Sensory Perception". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Fries-Knoblach, Janine; Steuer, Heiko; Hines, John (2014). The Baiuvarii and Thuringi: An Ethnographic Perspective. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 9781843839156.

- Geary, Patrick J. (1988). Before France and Germany: the creation and transformation of the Merovingian world.

- Lund, Julie (2017). "Connectedness with things. Animated objects of Viking Age Scandinavia and early medieval Europe". Archaeological Dialogues. 24 (1): 89–108. doi:10.1017/S1380203817000058. ISSN 1380-2038.

- Bill, Jan; Daly, Aoife (2012). "The plundering of the ship graves from Oseberg and Gokstad: an example of power politics?". Antiquity. 86 (333): 808–824. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00047931. ISSN 0003-598X.

- Wolfgang Hübener: Absatzgebiete frühgeschichtlicher Töpfereien nördlich der Alpen. Antiquitas Reihe 3 Bd. 6, Bonn 1969.

- Härke, Heinrich (2014-01-02). "Grave goods in early medieval burials: messages and meanings". Mortality. 19 (1): 41–60. doi:10.1080/13576275.2013.870544. ISSN 1357-6275.

- WEINER, ANNETTE B. (198). "inalienable wealth". American Ethnologist. 12 (2): 210–227. doi:10.1525/ae.1985.12.2.02a00020. ISSN 0094-0496.

- Wood, Ian (2013-09-26). The Modern Origins of the Early Middle Ages. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199650484.