Pyramid of Sahure

The Pyramid of Sahure (in ancient Egyptian Kha-ba Sahura (The rising of the ba spirit of Sahure)) is a late 26th century BC to 25th century BC pyramid complex built for the Egyptian pharaoh Sahure of the Fifth Dynasty.[8][lower-alpha 1] Sahure built the inaugural pyramid in Abusir after his direct predecessor, Userkaf, built his sun temple in the same area. Sahure's successors, Neferirkare Kakai, Neferefre, and Nyuserre Ini all built their monuments in the general vicinity. The complex's early visitors, John Shae Perring, Karl Richard Lepsius and Jacques de Morgan, did not conduct a thorough investigation, perhaps they were discouraged by its ruined state. It was first properly excavated by Ludwig Borchardt between March 1907 and 1908, who penned the seminal work on the topic Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Sahu-Re between 1910 and 1913.

| Pyramid of Sahure | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sahure's pyramid and causeway | ||||||||||||||

| Sahure | ||||||||||||||

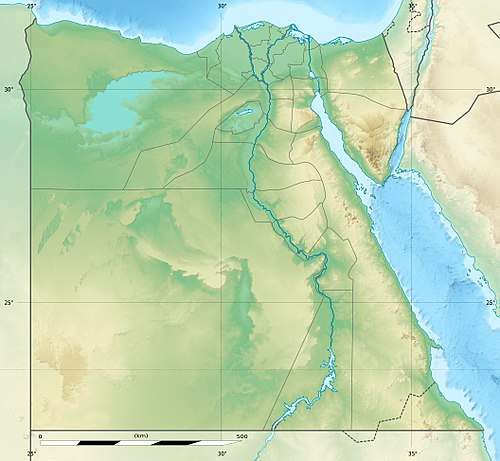

| Coordinates | 29°53′52″N 31°12′12″E | |||||||||||||

| Ancient name | Ḫˁ-bʒ Sʒḥw Rˁ Kha-ba Sahura[2] "The rising of the ba spirit"[3][4] of Sahure Alternatively translated as "The ba of Sahure appears"[5][6] or "Sahure's soul shines"[1] | |||||||||||||

| Constructed | Fifth Dynasty | |||||||||||||

| Type | True (now ruined) | |||||||||||||

| Material | Limestone | |||||||||||||

| Height | 47 m (154.2 ft)[3] | |||||||||||||

| Base | 78.75 m (258.4 ft)[3] | |||||||||||||

| Volume | 96,542 m3 (126,272 cu yd)[7] | |||||||||||||

| Slope | 50°11'14[3] | |||||||||||||

Location within Egypt | ||||||||||||||

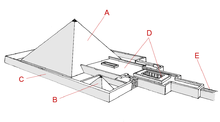

The monument consists of a main pyramid, mortuary temple adjacent the east face with a cult pyramid to its south, a valley temple on Abusir Lake, and a causeway linking the complex. The layout was developed by Sahure and adopted by succeeding kings of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasty, thus representing a milestone in pyramid complex construction. The monumentality of these constructions was drastically diminished, but, in tandem, the decorative program proliferated and temples were augmented by greater storeroom complexes. The monument is estimated to have had 10,000 m2 (110,000 sq ft) of finely carved relief adorning its walls, of which a mere 150 m2 (1,600 sq ft) has been preserved. Certain of these preserved reliefs is considered unrivalled in execution, such as a massive 8 m (26 ft) by 3 m (9.8 ft) hunting scene from the mortuary temple. The temple itself is remarkable for the array of valuable materials – such as granite, alabaster and basalt – that were used in its construction.

The main pyramid had a core of steps built from mud mortar bound, roughly hewn limestone blocks that were encased with fine white Tura limestone. Adjacent to its eastern face, the mortuary temple was built consisting of five basic elements: an entrance hall, an open courtyard, a five niche statue chapel, an offering room and storerooms. These had been used in mortuary temples since the reign of Khafre, but here again, Sahure's layout was adopted as standard in all subsequent such temples in the Old Kingdom. At the south-east corner of the main pyramid lay the enclosure of the cult pyramid, accessible either via a secondary entrance or a transverse corridor. The transverse corridor acted as an intersection separating the public and intimate temples, and connecting the various elements of the temple together. Beyond the temple's entrance hall, a 235 m (771 ft; 448 cu) long causeway led to the valley temple sited on the Abusir lake. In its rectangular plan, the valley temple had two entrances: its main on its east side, and an unexpected secondary entrance on its south. It remains unclear why a second entry point was built, though it may have been connected to a pyramid town to its south.

Sahure's temple became the object of a cult of Sekhmet around the Eighteenth Dynasty. The growing interest in Abusir heralded the first wave of destruction visited upon the sites monuments. Sahure's may have escaped this battering, a protection afforded it by the cult. Later, in the Twenty-Fifth and Twenty-Sixth Dynasties, the monuments once again stirred interest, as evidenced by the copying of the monuments relief decorations. Taharqa had various of Sahure's, Nyuserre's and Pepi II's reliefs copied for the restoration of the temple of Kawa (Sudan) in Nubia. In the Twenty-Seventh Dynasty, the Abusir monuments endured a second wave of destruction. Yet, Sahure's cult of Sekhmet may have saved it once more. The cult lasted until the Ptolemaic Kingdom, but by this time its influence had waned significantly. With the onset of the Roman period, the Abusir monuments, this time including Sahure's, were subjected to the third wave of destruction. Later, at the beginning of the Christian era, Sahure's temple became the site of a Coptic shrine, as evidenced by the recovery of pottery and graffiti dating to between the fourth and seventh century AD. From then on, until the late nineteenth century, the monuments were periodically farmed for limestone.

Location and excavation

.png)

Sahure choose a site near Abusir for his funerary monument,[16][1] thus constructing the first pyramid in the region.[17] Earlier, the founder of the Fifth Dynasty, Userkaf, had chosen Abusir as the location for his sun temple.[1][18] It is unclear why Userkaf chose such a remote site.[19] It may have been significant for the nearby cult of Ra, or, in the opinion of the Egyptologist Werner Kaiser, the southernmost point from which the gilded obelisk pyramidion of the temple of Re in Heliopolis could be seen.[1] It is clear, however, that his decision influenced the history of Abusir,[20] including Sahure's decision to build his monument there.[21] Three of the Abusir pyramids, those of Sahure, Neferirkare and Neferefre, are linked at the northwest corners by an imaginary line running to Heliopolis (Iunu).[22][18] The diagonal was broken by Nyuserre, who positioned his complex between those of Neferirkare and Sahure.[18]

Early excavators neglected to perform thorough investigations of Sahure's monument, perhaps discouraged by its ruined state.[23] In 1838, John Shae Perring, an engineer working under Colonel Howard Vyse,[24] cleared the entrances to the Sahure, Neferirkare and Nyuserre pyramids.[25] Perring was also the first person to enter the substructure of Sahure's pyramid.[23] Five years later, Karl Richard Lepsius, sponsored by King Frederick William IV of Prussia,[26][27] explored the Abusir necropolis and catalogued Sahure's pyramid as XVIII.[25] The pyramid was re-entered later by Jacques de Morgan, but he too did not explore further. It then remained ignored for fifty years, until the Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt visited the site.[23]

From 1902–8, Borchardt, working for the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (German Oriental Society), had the Abusir pyramids resurveyed and had their adjoining temples and causeways excavated.[25][28] From March 1907 to March 1908, Borchardt had Sahure's pyramid thoroughly investigated, and he had trial digs conducted at nearby sites, including Neferefre's unfinished pyramid.[29] He published his discoveries in the two-volume study Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Sahu-re (1910–13), which remains the standard work on the complex.[23]

In 1994, the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities decided to have the Abusir necropolis opened to tourism. In preparation, they had restorative works conducted at Sahure's pyramid.[30] The architect Zahi Hawass had a segment of Sahure's causeway cleaned and reconstructed, during which large relief decorated limestone blocks, that had been buried in the sand, were uncovered.[31] The reliefs found on these blocks were thematically and artistically unique[31] and shed new light on the decorative program of the complex.[30]

Mortuary complex

Layout

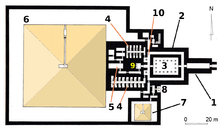

Old Kingdom mortuary complexes typically consist of five main components: (1) a valley temple; (2) a causeway; (3) a mortuary temple; (4) a cult pyramid; and (5) the main pyramid.[32] Sahure's is oriented on the east-west axis,[33] and contains all of these elements. Its 48 m (157 ft; 92 cu) tall main pyramid comprised six ascending steps of stone encased in fine white limestone,[34] with a cult pyramid located at the south-east corner,[35] and a mortuary temple, the standard-bearer for future variants,[3] adjacent its east face.[36] These elements were connected to the valley temple, situated on Abusir lake,[18][37] by a 235 m (771 ft; 448 cu) long limestone causeway.[18][38]

Sahure's monument represents a milestone in the development of pyramid construction.[39][40] Except for minor deviations, the complexes of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties were modelled after Sahure's.[39] The main pyramids were drastically reduced in size, and adopted simplified construction techniques.[41] The arrangement of the apartments of Sahure's mortuary temple became the model layout for subsequent temples of the type in the Old Kingdom.[42] Relief decoration advanced in wealth of subject matter and quality of workmanship[43][44] and temples were outfitted with expansive storeroom complexes.[45]

Sahure's temples and causeway are the most expertly decorated containing the most thematically diverse relief-work yet discovered from the Old Kingdom.[46] Across his entire complex, it is estimated that 10,000 m2 (110,000 sq ft) of finely carved relief adorned the walls.[3][47] His mortuary temple alone contained 370 linear metres (1,214 linear feet) of relief decorations. By contrast, Sneferu's mortuary temple contained 64 linear metres (210 linear feet) of relief decoration, Khufu's contained 100 linear metres (328 linear feet), and, Sahure's direct predecessor, Userkaf's contained 120 linear metres (394 linear feet).[45] The last king of the Old Kingdom, Pepi II's mortuary temple contained 200 linear metres (656 linear feet) of relief decoration, which indicates a decline following Sahure, as well.[48] Unfortunately, no more than 150 m2 (1,600 sq ft) of fragmentary relief has been preserved from Sahure's temple,[25] yet this is considered well-preserved.[49]

The mortuary temple had also been equipped with large storeroom complexes.[50][51] Of the temple's 4,246 m2 (45,700 sq ft) floorplan, 916 m2 (9,860 sq ft) were reserved for storerooms, accounting for 21.6% of its total area. This was a stark departure from the Fourth Dynasty. The 800 m2 (8,600 sq ft) temple of Sneferu's Red Pyramid at Dahshur, and 2,000 m2 (22,000 sq ft) temple of Khufu's Great Pyramid had no storerooms, while the 1,265 m2 (13,620 sq ft) temple of Khafre's pyramid reserved less than 200 m2 (2,200 sq ft) of space for storerooms, accounting for 15.8% of its total area.[50]

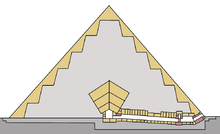

Main pyramid

Sahure's pyramid is situated upon a hill elevated 20 metres (66 ft) above the Nile valley. Although the subsoil of the area has never been investigated, evidence from the nearby mastaba of Ptahshepses suggests that the pyramid was not embedded into bedrock, but on a platform constructed from at least two layers of limestone.[30] The pyramid had a, likely horizontally layered,[lower-alpha 2] core comprising six ascending steps,[55] five of which remain.[56] The core consisted of low-grade roughly cut limestone,[55] bound with mud mortar,[4] and was encased by fine white limestone acquired from the nearby quarries of Maasara.[55]

Sahure's pyramid was constructed in a drastically different manner to those of the preceding dynasty. Its outer faces were framed using massive – at Neferefre's unfinished pyramid the single step contained blocks up to 5 m (16 ft) by 5.5 m (18 ft) by 1 m (3.3 ft) large[57] – roughly dressed grey limestone blocks well-joined with mortar. The inner chambers were similarly framed, but using significantly smaller blocks.[58] The core of the pyramid, between the two frames, was then packed with a rubble fill of limestone chips, pottery shards, and sand, with clay mortaring.[58][57][59] This method, while less time and resource consuming, was careless and unstable, and meant that only the outer casing was constructed using high quality limestone.[60]

Sahure's pyramid from the end of the causeway

Sahure's pyramid from the end of the causeway Model of Sahure's pyramid complex from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Model of Sahure's pyramid complex from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.jpg) Crumbling remains of Sahure's pyramid

Crumbling remains of Sahure's pyramid

Owing to the poor condition of the monument, information regarding its dimensions and appearance contain a degree of imprecision.[61] The pyramid had a base length of 78.5 m (258 ft; 149.8 cu) converging at 50° 30′ towards the apex 48 m (157 ft; 92 cu) high.[62] The architects made a notable error in demarcating the base, causing the southeast corner of the pyramid to extend 1.58 m (5.2 ft) too far east. Consequently, the base is not square.[55] A ditch was left in the north face of the pyramid during construction which allowed workers to build the inner corridor and chambers while the core was being erected around it, before filling it in with rubble.[18][63]

The pyramid is surrounded by a limestone paved courtyard, except for where the mortuary temple stood, and is accessed from the temple's north and south wings.[64] Enclosing the courtyard is a tall, rounded enclosure wall 3.15 m (10.3 ft; 6.01 cu) at its thickest.[65]

Substructure

The pyramid substructure access is found slightly above ground on the pyramid's north face.[55] A short descending corridor – lined with granite[18] – leads into a vestibule, beyond which the route is guarded by a pink granite portcullis,[55] either side of which the walls are lined with granite.[66] The descending corridor is 4.25 metres (14 ft) long with a slope of 24° 48′, and has a passage 1.27 m (4.2 ft) wide and 1.87 m (6.1 ft) high.[67][3] The corridor following – lined with limestone[18] – begins with a slight ascent before becoming horizontal – and lined with granite[18] – just prior to its terminus.[68] The ascending portion is 22.3 m (73 ft) long with a slope of 5°, whilst the horizontal section is 3.1 m (10 ft) long.[69]

Precise reconstruction of the substructure plan has been rendered impossible as a result of the extensive damage that stone thieves wrought on the chambers.[36] As a result, sources differ as to whether the funerary apartment – estimated to be 12.6 m (41 ft) east-west by 3.15 m (10.3 ft) north-south[3] – consisted of a single chamber,[18][66] or twin chambers.[36]

In the latter case, the antechamber lies directly on the vertical axis of the pyramid, whilst the burial chamber lies to its west.[36] The chamber(s) had a ceiling constructed from three gabled layers of limestone blocks,[36][18] which dispersed the weight from the superstructure onto either side of the passageway preventing collapse.[70] The largest blocks were estimated by Perring to be 10.6 m (35 ft; 20.2 cu) long, 3 m (9.8 ft; 5.7 cu) wide and 4 m (13 ft; 7.6 cu) thick. Despite their size and weight, all but two have been broken.[66] Inside the apartment's ruins, Perring found stone fragments – constituting the only discovered remains of the burial[18] – which he believed belonged to the king's basalt sarcophagus.[36]

.png)

.png)

Valley temple

Sahure's, now ruined, valley temple was situated on the shore of Abusir lake, on the edge of the desert.[18][37][71] It had a rectangular ground plan 32 m (105 ft; 61 cu) long by 24 metres (79 ft; 46 cu) wide and oriented on the north-south axis.[72] Its base is now around 5 m (16 ft) below ground level,[73] which has risen over the millennia due to the accumulation of silt deposits during the annual Nile flood.[37] The temple's walls slope inwards as they rise, their corners are formed into a convex torus mould up to a cavetto cornice with its own horizontal torus mould.[74]

The temple had two entrances.[75] Its main entrance, in the east, consisted of a landing ramp leading to a column adorned portico.[18][37][75][18] Its floor was paved with polished basalt, its walls had a red granite dado above which was limestone decorated with bas-relief, and it had a limestone ceiling that had been painted blue and decorated with relief-carved golden stars – representing the entrance into the Duat.[18][75][37] The columns were formed into date-palms, with leaves tied vertically to form capitals, and each column bore the king's titulary and name carved into the stone and painted green.[75] An alternate entrance was built on the south side, accessed by a canal leading to a ramp up to another columned portico, this time containing four red granite columns.[18][37] The columns, in contrast, were cylindrical in form and lacked any crown. This portico was also less deep and was paved with limestone.[75] It remains unclear, why this entrance was built.[76] The wall may belong to Sahure's pyramid town, named "The soul of Sahure comes forth in glory".[18]

.png)

The entrances were connected by passages to a T-shaped hall equipped with two columns.[37][75] Borchardt describes the room as "double staggered" (doppel gestafellt). It has a transverse space with a narrowed recess in its rear wall containing the two columns – the first stagger. Then an even narrower, recess in the first's rear wall – the second stagger.[77] The room was originally adorned with polychromatic relief,[37] and contained a scene depicting the king, as a sphinx or griffin, trampling captive Asiatic and Libyan enemies led to him by the gods.[75][18][77] The room connects to two more rooms: a room with a staircase up to the roof terrace at the south end, and causeway at its rearmost recess.[18][78]

A relief depiction of troops from Sahure's valley temple can be contrasted with similar imagery in Userkaf's complex. In Sahure's scene, the soldiers are carved with near identical postures, a stark contrast to Userkaf's confused arrangement of overlapping figures. The latter has greater dynamism inducing more interest, whilst the former is more readily understood. The monotony of Sahure's scene was balanced by craftsmen introducing detail in the musculature and facial features of the figures.[79]

Causeway

A 235 m (771 ft; 448 cu) long, slightly inclined[80] limestone causeway[38] connected the valley temple to the mortuary temple.[18] The causeway was roofed, with narrow slits left in the ceiling slabs allowing light to enter illuminating its polychromatic bas-relief covered walls.[81] These included scenes with seemingly apotropaic functions, such as a scene of the king represented as a sphinx crushing Egypt's enemies under his paw.[37] Other scenes presented include offering bearers, animal slaughter,[82] and the transport of the gilded pyramidion to the construction site.[36][31] Only the base of the causeway, made of large limestone blocks, has been preserved.[37]

.png)

The scene depicting emaciated Bedouins, who have been reduced, through starvation, to skin and bone – had significant historical implications.[31] The scene was thought only to exist in Unas' causeway, and was thus believed to be unique eyewitness testimony to the declining living standards of Saharan Bedouins brought about by the end of the Sahara wet phase in the middle of the 3rd millennium BC.[31][83] The discovery of an identical scene in Sahure's causeway casts significant doubt onto this hypothesis.[83] Instead, the Egyptologist Miroslav Verner suggests that the Bedouins might have been brought into the pyramid town to demonstrate the hardships faced by pyramid builders bringing in higher quality stone from remote mountain areas.[31]

A second discovered scene has implications for Fifth Dynasty genealogy.[lower-alpha 3] In this scene, Sahure is surrounded by his family in the palace garden Wtjs-nfrw-Sahw-ra (Extolled is Sahure's beauty). The image confirms the identity of Sahure's consort, Meretnebty, and his twin sons, Ranefer and Netjerirenre. Ranefer, who is depicted closer to Sahure and bears the titles "king's son" and "chief lector-priest", may have been Sahure's eldest son, ascending to the throne as Neferirkare Kakai. Netjerirenre may instead be the ephemeral ruler Shepseskare, who took the throne after Neferefre's early death.[94][lower-alpha 4]

Another significant relief discovered depicts a procession of ships, led by the king, being moored at an unidentified location. The relief originated on the causeway south wall, and although the location depicted cannot be identified, a corresponding relief on the same wall depicts the king, his mother and wife, awaiting the arrival of ships carrying myriad goods – particular emphasis was placed on the Commiphora myrrha trees (nht n ˁntw)– from the land of Punt.[101] Sahure's is the earliest recorded voyage taken by the Egyptians to Punt[102] acquiring myrrh, electrum and wood from there.[103]

Sahure is further depicted extracting myrrh with an adze from the tree in one scene, and banqueting with his family, including his sons, and officials near the tree in another.[104] The trees depicted may not be Commiphora myrrha, as the use of an adze to extract resin was typically reserved for the Boswellia tree, and moreover the colour of the resin in Sahure's scene was identified by the Egyptologist Tarek El-Awady as yellow-ish brown, like Boswellia frankincense, and not red, like myrrh.[105]

Mortuary temple

The mortuary temple was a voluminous, rectangular building oriented along the east-west axis,[38] and situated on a level surface built from two layers of limestone blocks in front of the main pyramid's east face.[36][106] In its layout, Sahure's mortuary temple represented the "conceptual beginning" of all subsequent such temples of the Old Kingdom.[3][107] It contained five basic elements, exemplified in the temple of Khafre: an entrance hall, an open courtyard, a five niche statue chapel, an offering hall, and storerooms.[75][38][71] The dominant building material used in its construction, here as elsewhere, was limestone, but substantial valuable materials such as red and black granite, alabaster and basalt were also incorporated.[36] The temple's outer façade was measured to be inclined at 82° up to a cavetto cornice with torus mould.[108]

Entrance hall

The transition between causeway and temple was marked by a large granite gate leading into the mortuary temple's entrance hall.[109][56] In the Fifth Dynasty, it was of the standard size of 21 m (69 ft; 40 cu) long, 5.25 m (17.2 ft; 10.02 cu) wide, and 6.8 m (22 ft; 13.0 cu) tall.[110] The hall has suffered significantly, rendering a precise reconstruction impracticable.[111] It had a limestone floor, its walls had red granite dado above which was, probably, limestone decorated with painted bas-relief scenes,[112][36] and was covered by a stone barrel vault ceiling which had slits in its tympanum allowing the enclosure to be dimly lit.[110] Contemporary sources identify this room as the pr-wrw meaning "House of the Great Ones",[36][110] and it may be a replica of the hall of the royal palace, where nobles were received and certain rituals performed.[82] At its end, a granite doorway led to a closed corridor surrounding an open courtyard.[106][3]

Corridor and courtyard

The corridor was paved with basalt, and its walls had a 1.57 m (5.2 ft; 3.00 cu) granite dado, above which they were decorated with colourful relief.[113] On its north wall, scenes depict the king fishing and hunting wildfowl, while on the south wall the king is depicted hunting – antelopes, gazelles, deer and other horned animals are shepherded into an enclosure for the king to shoot with his bow and arrow, after which hound dogs seize and kill the animals, elsewhere hyenas are observed poaching, and hedgehogs and jerboa scatter into their holes[114] – whilst his courtiers observe.[115] A masterful depth of detail has been incorporated into the latter scene, which measured 8 m (26 ft) long by 3 m (9.8 ft) high.[116][117] The sedated posture of the king's courtiers, representing order, is juxtaposed against the mass of wounded and frightened animals depicted in a variety of postures and facing various directions, representing chaos.[116] The imposing figure that is Sahure is unrivalled in any other example, and the gruesome detail of the injured animals is unreplicated. The figure of a hyena, pawing at an arrow in its jaw, reappears frequently in the Middle and New Kingdom, an homage to the relief from Sahure's temple.[117] Ptahhotep's tomb in Saqqara contains an abridged, and slightly less skillfully executed, copy of this hunting scene.[118]

The architect Mark Lehner suggests that the corridor represented the untamed wild, surrounding a clearing – the open courtyard – of which the king was guarantor.[70] Referencing reliefs depicting ships on the east-corridor west-wall and west-corridor (transverse corridor) east-wall, the Egyptologist Dorothea Arnold contends that the courtyard and corridor form an architectural unit analogous to the Egyptian benben myth. The other reliefs present symbolize the king's role as guarantor of order and prosperity on the sacred island.[120] Among the reliefs of this room a significant discovery was made. One of the individuals present has been modified to include a brief inscription identifying them as "Neferirkare King of Upper and Lower Egypt" (nsw-bit Nfr-jrj-k3-rˀ). From this detail, Kurt Sethe, who was responsible for compiling and preparing the scenes for publication, developed the hypothesis that Neferirkare Kakai and Sahure were brothers, and that Neferirkare had had the relief corrected after ascending to the throne.[121]

The open courtyard was paved with polished basalt and lined with sixteen red granite columns, supporting the roof of an ambulatory.[112] Aside from an alabaster altar in the north-west corner decorated with scenes of sacrifice, the open courtyard is bare,[112] though it originally had statues of the pharaoh placed between the columns,[122] and may once also have contained statues of kneeling captives.[123] Eleven of the original sixteen granite columns were found in the temple.[36][124] Each was 6.4 m (21 ft) tall,[124] and carved into the form of date palms, symbolising fertility and immortality, upon which the king's name and titulary was inscribed[36] and painted in green.[125] The Two Ladies appear on these columns as well, Nekhbet, the vulture goddess, in the south half representing Upper Egypt, and Wadjet, the cobra goddess, in the north half representing Lower Egypt. Above, a red granite architrave bore the royal titulary, and further supported the limestone ceiling.[126][127] The ambulatory's blue painted ceiling was decorated with yellow stars, whilst its limestone walls were decorated with polychrome bas-reliefs, fragments of which have been preserved, depicting the king's victory over his enemies – on the north wall Asiatics, on the south Libyans – and the acquired spoils.[128][112] In a particular scene, showing the capture of animals, supplementary inscriptions identify the quantities seized: "123,440 head of cattle, 223,400 asses, 232,413 deer, and 243,688 sheep".[112][71] In another scene, the family of a Libyan chief beg for his life to be spared whilst the king prepares to execute him.[70][112] Under the northern ambulatory, a relief of exemplary craftsmanship depicting precious oil vases and Syrian brown bears was found. The figures were given rounded edges so that they simultaneously blend in with the background and stand out clearly. Much of the paint used has been preserved: a dark red-brown colour was used for the vase and a yellow-brown for the bear's fur.[129] Up to a further eleven scenes remain too fragmentary to be reconstructed.[112]

Basalt paving of the courtyard

Basalt paving of the courtyard Remnant of the massive granite architrave inscribed with Sahure's titulary

Remnant of the massive granite architrave inscribed with Sahure's titulary Depiction of Sahure's mortuary temple as it appeared in the Old Kingdom

Depiction of Sahure's mortuary temple as it appeared in the Old Kingdom Palmiform capital of a column from Sahure's mortuary temple

Palmiform capital of a column from Sahure's mortuary temple

Transverse corridor and storage galleries

Beyond the courtyard is a transverse (north-south) corridor which separates the public outer from the private inner temple,[70] which only priests were allowed to access.[123] The corridor further served as an intersection connecting the outer and inner temples, the courtyard surrounding the pyramid, and the cult pyramid. At its northern end was a staircase up to the roof terrace.[130] Its floor was paved with basalt, as the courtyard was, and its walls had a granite dado, above which was bas-relief decorated limestone.[130] On the north half of the corridor's east wall is a relief, considered by the Egyptologist Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards to be amongst the most interesting in the temple, that depicts the king and his court observing the departure of twelve sea-going vessels, probably on expedition to Syria or Palestine.[114] In the south-half, a similar scene depicts the king and his court awaiting the arrival of ships laden with cargo and several Asiatics, who do not appear to be prisoners, indicating either a commercial or, perhaps, diplomatic mission.[114][130] In the centre of the west wall of the corridor was an alabaster staircase that led into the five niche statue chapel.[130][70][131]

Flanking the staircase were two deep niches, each containing two granite papyriform columns 3.65 metres (12 ft) high. The columns supported an architrave, a fragment of which has been found in the oil press of St. Jeremiah monastery in Saqqara.[130] The niche's walls were decorated with reliefs depicting processions of offering bearers, and they had recessed side doors leading to two-story storage galleries.[70][131] The northern gallery consisted of ten rooms arranged in two rows, each outfitted with its own staircase – cut directly into the limestone walls[51] – leading to the second story.[131] These held cult objects used for the temple rituals.[51] The southern gallery consisted of sixteen or seventeen rooms, also arranged in two rows and outfitted with staircases, that probably held sacrificial offerings.[131][51] Reliefs in the corridors leading to the galleries even included ritual instructions, such as "presentation of gold" or "sealing a box containing incense" found in the north and south corridors respectively.[132]

- Transverse corridor relief depicting a returning naval expedition (Rückkehrende Seeschiffe)[133]

- The southern storage gallery where offerings were stored

.jpg) Carved stone steps of a two story storage room

Carved stone steps of a two story storage room

Statue chapel

The transverse corridor staircase leads into the five niche statue chapel,[131] a room with significant religious importance.[123] Accessed through a double-door, it had a floor paved with white alabaster,[70] red granite sheathing in the niches and dado, fine white limestone sheathed walls elsewhere which was lavishly decorated in relief, and a limestone ceiling decorated with stars evoking the night-sky of the Duat.[130] A small staircase stood before each niche, which was once occupied by a statue, none of which have been preserved.[130] It was originally assumed that each statue represented one of the king's five names, but the Abusir Papyri, discovered in the nearby pyramid of Neferirkare, indicate otherwise. The papyri identify that the central statue represented the king as Osiris, while the two outermost ones represented him as the king of Upper Egypt, and the king of Lower Egypt.[132][134] The remaining two are not identified.[123] Exiting the chapel to the south is a path leading through two rooms[135] – including a rectangular vestibule that appears to be a predecessor of the antichambre carée, first found in Nyuserre's mortuary temple[136] – passing around a great stone massif and into the westernmost room of the temple, the offering hall.[134][137]

Offering hall and auxiliary rooms

The offering hall of the temple held the most significance for the royal mortuary cult.[134] The sanctuary was 13.7 metres (45 ft; 26 cu) in length and 4.6 metres (15 ft; 9 cu) wide.[131] It was entered through a black granite door, that opened up to a white alabaster paved floor, walls with dado of black granite above which was fine white limestone decorated with polychromatic bas-relief depicting divinities bringing offerings to the king, and covered along its length by a vaulted ceiling with painted stars.[134] A low alabaster altar stood at the west wall,[131] at the foot of a granite false door, possibly covered in copper or gold, through which the spirit of the king would enter the room to receive his meal, before returning to his tomb.[138] Unusually, the false door has been crudely fashioned, and bears none of the names, titles, or sacrificial formulas that are expected to be found. This led Borchardt to speculate that the door may have originally been sheathed with metal, that was eventually stolen by thieves.[139] The room also originally contained a black granite statue and an offering basin, located in a recessed niche in its south-west corner, with an outflow of copper piping.[70][56] In the north wall, a granite doorway gives access to five auxiliary rooms,[70] which served the offering hall.[51]

Drainage system

Sahure's temple had an elaborate drainage system[140] including more than 380 metres (1,247 ft) of copper piping.[51][lower-alpha 5] Rainfall captured on the roof was funneled out through stone lion-head spouts fit onto the tops of the outer walls. The choice of the lion-head may relate to the ancient Egyptian belief that Seth and other inimical deities could manifest themselves in rain. The lion, a symbolic protector of sacred ground, consumed the harmful spirits and ejected harmless water. Where no roof existed, gaps around the base of the outer walls collected the water, conducting it out using channels cut into the paving.[140][71] Water and other liquids used in rituals and ceremonies, which had become impure and thus dangerous to touch, were removed using the drainage system.[140][71][51] Five stone and copper plated basins, each with a lead plug to fit the vent, were placed around the inner temple.[140] The first was found in the offering hall, two more were in the auxiliary rooms beyond it, a fourth in the corridor leading up to the offering hall, and the fifth in the northern magazine gallery.[140][70][51] These were connected via an intricate network of copper pipes laid beneath the temple, which lead down the length of the causeway before terminating at an outlet on its southern side.[142]

.png) Limestone channels through which water and other liquids were drained

Limestone channels through which water and other liquids were drained.png) Lead plug of a copper basin from the mortuary temple

Lead plug of a copper basin from the mortuary temple.png) Carved limestone channels departing the offering hall

Carved limestone channels departing the offering hall

Cult pyramid

By the main pyramid's south-east corner, confined to a separate enclosure, lay a cult pyramid.[35] The enclosure is accessed from either the southern end of the transverse corridor,[51] or through a portico – the side-entrance to Sahure's mortuary temple[143] – flanked by two granite columns bearing Sahure's royal titulary.[70] The portico floor was paved with basalt, as were the dado of its walls, above which the walls were built of limestone and decorated with polychromatic relief. The reliefs portrayed rows of deities, nome and estate personifications, and fertility figures – all clutching was-sceptres and ankh signs – marching into the temple. An accompanying inscription bears their message to the king: "We give you all life, stability, and dominion, all joy, all offerings, all perfect things that are in Upper Egypt, since you have appeared as king of Upper and Lower Egypt alive forever".[143] Behind the portico, a room with two exits allows access to the transverse corridor in the north or to an oblong room preceding the cult pyramid in the south.[144]

The cult pyramid had a core ascending in two or three steps,[51][145] composed primarily of limestone block debris framed by yellow limestone blocks, and then encased with white limestone blocks – the same method of construction as used in the main pyramid.[146] It had a base length of 15.7 m (52 ft; 30.0 cu) converging at 56° towards the apex 11.6 m (38 ft; 22.1 cu) high.[62] From the north face,[147] a bent corridor – initially descending, then switching to an ascent – leads into the miniature pyramid's sole chamber: an east-west oriented burial room found slightly below ground level. The chamber was found void of any content, and its walls had been severely damaged by stone thieves.[35]

The purpose of the cult pyramid remains unclear. Its burial chamber was not used for burials, but instead appears to have been a purely symbolic structure.[148] It may have hosted the pharaoh's ka (spirit),[149] or a miniature statue of the king.[150] It may have been used for ritual performances centering around the burial and resurrection of the ka spirit during the Sed festival.[150]

.png) Remains of the cult pyramid, with the lowest course of white limestone still intact

Remains of the cult pyramid, with the lowest course of white limestone still intact Remains of the mortuary temple; the side entrance columns to the right of image

Remains of the mortuary temple; the side entrance columns to the right of image Granite column of the side entrance bearing Sahure's name in cartouche and additional formula

Granite column of the side entrance bearing Sahure's name in cartouche and additional formula

Necropolis

A necropolis on the transverse corridor's southern end by the cult pyramid, is accessed through the side-entrance. It is largely unexplored, but is thought to be the burial ground of Sahure's consort, Meretnebty, and son, Netjerirenre.[51]

Later history

Cult of Sekhmet

.png)

During the Eighteenth Dynasty, the south corridor of Sahure's mortuary temple[114] became home to a cult of Sekhmet.[121] Its early history is unknown, and though Borchardt suggested that the cult had its origins in the Middle Kingdom, there is no evidence to support this conjecture. The earliest attested royal connection to cult is Thutmose IV, of the Eighteenth Dynasty,[152] followed later by Ay and Horemheb.[153] Amenhotep III, of the Eighteenth Dynasty,[154] has been connected to the temple through a faience object bearing his name, as have Seti I and Ramesses II, of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt,[154] through restoration inscriptions bearing their names.[155] The renewed attention had a negative consequence as the first wave of dismantlement of the Abusir monuments, particularly for the acquisition of valuable Tura limestone, arrived with it. Sahure's mortuary temple may have been spared at this time due to the presence of the cult.[156] The cult's influence likely waned after the end of Ramesses II's reign, becoming a site of local worship only.[157]

The Abusir necropolis and Sahure's cult garnered attention once again in the Twenty-Fifth and/or Twenty–Sixth Dynasties, as evidenced by the copying of relief art from the monuments.[158] Taharqa, of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty,[159] had various reliefs replicated – such as images of the king crushing his enemies as a sphinx[160] – from the mortuary temple's of Sahure, Nyuserre, and Pepi II for the restoration of the temple of Kawa in Nubia.[161] In the late Twenty-Sixth to the early Twenty-Seventh Dynasty, a new period of dismantlement appears to have been visited on the monuments. Sahure's was once again spared, protected by the cult into the Ptolemaic Kingdom, though it had very reduced influence at this time.[162] A third wave of dismantlement of the Abusir monuments is clearly attested in the Roman period by the abundant remains of mill-stones, lime production facilities, and worker shelters.[163] At the beginning of the Christian era, Copts founded a shrine in the temple,[121] as shown by pottery and Coptic graffiti dating to between the fourth and seventh centuries AD.[164] Periodic farming of the monuments for limestone continued at least until the end of the 19th century AD.[165]

Notes

- Proposed dates for Sahure's reign: c. 2506–2492 BC,[8][9] c. 2491–2477 BC,[10] c. 2487–2475 BC,[11][12] c. 2458–2446 BC,[13][14] c. 2385–2373 BC.[15]

- Borchardt, who conducted the excavations at Sahure's pyramid, described the pyramid core as composed of accretion layers.[52][53] This was challenged by Vito Maragioglio and Celeste Rinaldi who conducted careful examinations of pyramidal architecture in the Old Kingdom and failed to find blocks lying on a slant in any Fourth or Fifth Dynasty pyramid they studied. Rather, they found that in each instance these blocks were always set horizontally leading them to reject the accretion layer hypothesis.[52] The theory was effectively disproven by the Czech excavation team at Abusir led by Miroslav Verner,[52][53] whereupon investigating Neferefre's unfinished pyramid, they discovered four or five horizontally layered courses of limestone blocks and an inner line of blocks framing the inner chambers.[54]

- Deciphering the origins and genealogy of the Fifth Dynasty has been a complex problem for historians due to the dearth and ambiguity of available historical sources.[84] In the Westcar Papyrus the first three kings of the Fifth Dynasty – Userkaf, Sahure and Neferirkare – are described as brothers borne of the union of Re and Redjedet, the wife of a priest of Re in Sakhebu.[84][85][86] The relationship between the founder of the Fifth Dynasty, Userkaf, and his predecessors is unclear.[87] He is traditionally viewed as the son of Neferhetepes,[88][89] and thus a grandson of Djedefre.[88] Userkaf's wife is believed to be Khentkaus I, daughter of Menkaure[90] and "mother of the two kings of Upper and Lower Egypt" Sahure and Neferirkare.[91][92] Sahure thus appears to have been succeeded by his brother, instead of his eldest son,[91][93][12][86] Netjerirenre.[8] Neferirkare had two sons with Khentkaus II, "mother of two kings of Upper and Lower Egypt" Neferefre and Nyuserre.[91] The identity of an ephemeral ruler, Shepseskare, is unknown, but his reign is placed between either Neferirkare and Neferefre,[86] or Neferefre and Nyuserre.[8]

- Miroslav Verner and Miroslav Bárta suggest the following lineage for the Fifth Dynasty: Khentkaus I with an unknown partner has two sons, Shepseskaf and Userkaf.[95][96] Userkaf with his consort, Neferhetepes, has a son, Sahure.[94][97] Sahure with his consort, Meretnebty, has twin sons, Ranefer (probably Neferirkare) and Netjerirenre.[94][98][96] Neferirkare with his consort, Khentkaus II, has two sons, Neferefre and Nyuserre Ini.[98][96] The identity of Shepseskare remains unclear, though he may plausibly have been Netjerirenre[94][99] or a son of Neferefre with a wife Khentkaus III, whose tomb was found south of Neferefre's mortuary temple.[100]

- A section of piping recovered during Borchardt's investigations was tested by Dr. Rathgen. It had a composition of 96.47% copper, 0.18% iron, 3.35% chlorine, oxygen, etc, and traces of arsenic.[141]

References

- Verner 2001d, p. 280.

- Brugsch 2015, p. 88.

- Lehner 2008, p. 143.

- Hellum 2007, p. 100.

- Arnold 2003, p. 207.

- Altenmüller 2001, p. 598.

- Bárta 2005, p. 180.

- Verner 2001b, p. 589.

- Altenmüller 2001, p. 599.

- Clayton 1994, p. 30.

- Shaw 2003, p. 482.

- Málek 2003, p. 100.

- Lehner 2008, p. 8.

- Allen et al. 1999, p. xx.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 288.

- Arnold 2003, p. 3.

- Verner 1994, p. 68.

- Lehner 2008, p. 142.

- Verner 2002, p. 41.

- Verner 2002, pp. 41–42.

- Verner 1994, pp. 67–68.

- Verner 1994, p. 135.

- Verner 2001d, p. 281.

- Lehner 2008, p. 50.

- Edwards 1999, p. 97.

- Peck 2001, p. 289.

- Lehner 2008, p. 54.

- Verner 2001a, p. 7.

- Verner 1994, p. 216.

- Verner 2001d, p. 283.

- Verner 2002, p. 44.

- Bárta 2005, p. 178.

- Lehner 2008, p. 19.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 284 & 463.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 53 & 289.

- Verner 2001d, p. 285.

- Verner 2001d, p. 290.

- Verner 2001d, p. 49.

- Verner 2001d, p. 46.

- Verner 2002, p. 42.

- Verner 1994, pp. 68 & 73.

- Verner 1994, p. 71.

- Verner 1994, pp. 68–70.

- Verner 2001c, p. 90.

- Bárta 2005, p. 185.

- Verner 1994, pp. 69–70.

- Verner 2002, p. 43.

- Arnold 1999, p. 98.

- Arnold 1997, p. 73.

- Bárta 2005, p. 186.

- Verner 2001d, p. 289.

- Sampsell 2000, Vol 11, No. 3 The Ostracon.

- Verner 2002, pp. 50–52.

- Lehner 2008, p. 147.

- Verner 2001d, p. 284.

- Bárta 2015, Abusir in the Third Millennium BC.

- Verner 2001d, p. 97.

- Verner 1994, p. 139.

- Lehner 2008, p. 15.

- Verner 1994, p. 140.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 283–284.

- Verner 2001d, p. 463.

- Lehner 1999, p. 784.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 26.

- Borchardt 1910, pp. 26 & 67.

- Edwards 1975, p. 185.

- Stadelmann 1985, p. 165.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 284–285.

- Stadelmann 1985, p. 166.

- Lehner 2008, p. 144.

- Hellum 2007, p. 101.

- Stadelmann 1985, pp. 170–171.

- Verner 1994, p. 70.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 7.

- Edwards 1975, p. 179.

- Verner 2001d, p. 179.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 8.

- Borchardt 1910, pp. 8–9.

- Allen et al. 1999, pp. 342–343.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 11.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 289–290.

- Arnold 1999, p. 94.

- Verner 2001d, p. 337.

- Verner 2015, p. 86.

- Málek 2003, p. 98.

- Altenmüller 2001, p. 597.

- Dodson 2015, p. 33.

- Grimal 1992, p. 75.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 53.

- Clayton 1994, p. 60.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 64.

- Clayton 1994, p. 46.

- Grimal 1992, p. 76.

- Verner 2007, p. 9.

- Verner 2015, pp. 87 & 90.

- Bárta 2017, p. 5.

- Bárta 2017, p. 6.

- Verner 2015, pp. 89–90.

- Verner 2015, p. 89.

- Verner 2015, p. 90.

- Billing 2018, pp. 41–42.

- Dodson 2015, p. 36.

- Wachsmann 2018, p. 19.

- Billing 2018, p. 42.

- Espinel 2017, ˁntw, ˁndw, and mḏt.

- Wilkinson 2000, p. 122.

- Arnold 1997, p. 63.

- Borchardt 1910, pp. 67 & Abb. 86–87.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 49 & 285.

- Arnold 2003, p. 174.

- Edwards 1975, pp. 179–181.

- Edwards 1975, p. 181.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 12.

- Edwards 1975, p. 182.

- Lehner 2008, pp. 143–144.

- Arnold 1999, pp. 91–92.

- Allen et al. 1999, pp. 336–337.

- Borchardt 1910, pp. 13–14.

- Borchardt 1913, p. Blatt 17.

- Arnold 1999, pp. 94–96.

- Verner 2001d, p. 287.

- Verner 1994, p. 72.

- Verner 2001d, p. 50.

- Arnold 1996, p. 46.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 16.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 285–287.

- Borchardt 1910, pp. 15–16.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 50 & 287.

- Allen et al. 1999, p. 333.

- Verner 2001d, p. 288.

- Edwards 1975, p. 183.

- Arnold 1999, p. 97.

- Borchardt 1913, pp. Blatt 12 & 13.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 52 & 288.

- Arnold 1997, p. 67.

- Megahed 2016, p. 240.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 21.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 52–53.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 288–289.

- Edwards 1975, p. 184.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 78.

- Edwards 1975, pp. 184–185.

- Allen et al. 1999, p. 338.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 25.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 73.

- Borchardt 1910, pp. 73–74.

- Borchardt 1910, p. 74.

- Verner 2001d, p. 53.

- Lehner 2008, p. 18.

- Arnold 2005, p. 70.

- Borchardt 1913, p. Blatt 29.

- Málek 2003, p. 485.

- Bareš 2000, pp. 7–8.

- Shaw 2003, p. 485.

- Bareš 2000, pp. 8–9.

- Bareš 2000, p. 9.

- Bareš 2000, p. 11.

- Bareš 2000, p. 12.

- Shaw 2003, p. 486.

- Kahl 2000, pp. 225–226.

- Grimal 1992, pp. 347–348 & 394.

- Bareš 2000, pp. 13–14.

- Bareš 2000, pp. 14–15.

- Bareš 2000, p. 15.

- Bareš 2000, p. 16.

Sources

- Allen, James; Allen, Susan; Anderson, Julie; et al. (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-8109-6543-0. OCLC 41431623.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2001). "Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 597–601. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, Dieter (1996). "Hypostyle Halls of the Old and Middle Kingdom?". Studies in Honor of William Kelly Simpson. 1. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. pp. 39–54. ISBN 0-87846-390-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, Dieter (1997). "Royal cult complexes of the Old and Middle Kingdoms". In Schafer, Byron E. (ed.). Temples of Ancient Egypt. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 31–85. ISBN 0-8014-3399-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, Dieter (2003). The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-465-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, Dieter (2005). "Royal cult complexes of the Old and Middle Kingdoms". In Schafer, Byron E. (ed.). Temples of Ancient Egypt. London, New York: I.B. Taurus. pp. 31–86. ISBN 978-1-85043-945-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, Dorothea (1999). "Royal Reliefs". Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 83–101. ISBN 978-0-8109-6543-0. OCLC 41431623.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bareš, Ladislav (2000). "The destruction of the monuments at the necropolis of Abusir". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 1–16. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bárta, Miroslav (2005). "Location of the Old Kingdom Pyramids in Egypt". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 15 (2): 177. doi:10.1017/s0959774305000090.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bárta, Miroslav (2015). "Abusir in the Third Millennium BC". CEGU FF. Český egyptologický ústav. Retrieved 1 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bárta, Miroslav (2017). "Radjedef to the Eighth Dynasty". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

- Billing, Nils (2018). The Performative Structure: Ritualizing the Pyramid of Pepy I. Leiden & Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-37237-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1910). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs S'aḥu-Re. Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Abusir 1902 - 1908 ; 6 : Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft ; 14 (in German). 1. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. OCLC 406055066. Retrieved 2019-09-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1913). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs S'aḥu-Re. Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Abusir 1902 - 1908 ; 7 : Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft ; 26 (in German). 2. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. OCLC 741989104. Retrieved 2019-09-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brugsch, Heinrich Karl (2015) [1879]. Smith, Philip (ed.). A History of Egypt under the Pharaohs, Derived Entirely from the Monuments : To which is added a memoir on the exodus of the Israelites and the Egyptian Monuments. 1. Translated by Seymour, Henry Danby. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-08472-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05128-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dodson, Aidan (2015). Monarchs of the Nile: New Revised Edition. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-716-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, Iorwerth (1975). The pyramids of Egypt. Baltimore: Harmondsworth. ISBN 978-0-14-020168-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, Iorwerth (1999). "Abusir". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Espinel, Andrés Diego (2017). "Chapter 3: The scents of Punt (and elsewhere): trade and functions of snṯr and ˁntw during the Old Kingdom". In Incordino, Ilaria; Creasman, Pearce Paul (eds.). Flora Trade Between Egypt and Africa in Antiquity. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781785706394.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hellum, Jennifer (2007). The Pyramids. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32580-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kahl, Jochem (2000). "Die Rolle von Saqqara und Abusir bei der Überlieferun altägyptischer Jenseitsbücher". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000 (in German). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 215–228. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lehner, Mark (1999). "pyramids (Old Kingdom), construction of". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 778–786. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Málek, Jaromír (2003). "The Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2160 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 83–107. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Megahed, Mohamed (2016). "The antichambre carée in the Old Kingdom. Decoration and function". In Landgráfová, Renata; Mynářová, Jana (eds.). Rich and great: studies in honour of Anthony J. Spalinger on the occasion of his 70th Feast of Thoth. Prague: Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Arts. pp. 239–259. ISBN 9788073086688.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peck, William H. (2001). "Lepsius, Karl Richard". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 289–290. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sampsell, Bonnie (2000). "Pyramid Design and Construction – Part I: The Accretion Theory". The Ostracon. Denver. 11 (3).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stadelmann, Rainer (1985). Die Ägyptischen Pyramiden: vom Ziegelbau zum Weltwunder. Kulturgeschichte der antiken Welt, 30 (in German). Mainz: von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-0855-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (1994). Forgotten pharaohs, lost pyramids: Abusir (PDF). Prague: Academia Škodaexport. ISBN 978-80-200-0022-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (2001a). "Abusir". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Old Kingdom". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 585–591. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (2001c). "Pyramid". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 87–95. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (2001d). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1703-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (2002). Abusir: Realm of Osiris. Cairo; New York: American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-424-723-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (2007). "New Archaeological Discoveries in the Abusir Pyramid Field". Archaeogate: Egittologia (in Italian and English). Archived from the original on 2009-04-27. Retrieved 2019-09-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (2015). "The miraculous rise of the Fifth Dynasty – The story of Papyrus Westcar and historical evidence". Prague Egyptological Studies (XV): 86–92. ISSN 1214-3189.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wachsmann, Shelley (2018). Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station: Texas A & M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-080-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05100-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Zahi Hawass, Miroslav Verner: Newly Discovered Blocks from the Causeway of Sahure (Archaeological Report). In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo. (MDIAK) vol. 51, von Zabern, Wiesbaden 1995, pp. 177–186.

- Tarek el-Awady: King Sahure with the Precious Trees from Punt in a Unique Scene, in: Proceeding of “Art and Architecture of the Old Kingdom”, Prague 2007 pp. 37–44.

- Tarek el-Awady: The Royal Navigation Fleet of Sahure, in: Study in Honor of Tohfa Handousa, ASAE (2007).

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyramid of Sahure. |