Professor Moriarty

Professor James Moriarty is a fictional character in some of the Sherlock Holmes stories written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Moriarty is a machiavellian criminal mastermind whom Holmes describes as the "Napoleon of crime". Doyle lifted the phrase from a Scotland Yard inspector who was referring to Adam Worth, a real-life criminal mastermind and one of the individuals upon whom the character of Moriarty was based. The character was introduced primarily as a narrative device to enable Doyle to kill Sherlock Holmes, and he only featured in two of the Sherlock Holmes stories. However, in adaptations, he has often been given a greater prominence and treated as Sherlock Holmes' archenemy.

| Professor Moriarty | |

|---|---|

| Sherlock Holmes character | |

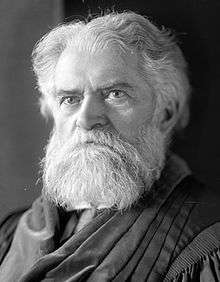

Professor Moriarty, illustration by Sidney Paget which accompanied the original publication of "The Final Problem" | |

| First appearance | The Final Problem |

| Created by | Arthur Conan Doyle |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | James Moriarty |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Professor of mathematics (former) Criminal mastermind |

| Family | One or two brothers[1] |

| Nationality | British |

Appearances in works

Professor Moriarty's first and only appearance occurred in the 1893 short story "The Adventure of the Final Problem" (set in 1891[2]), in which Holmes, on the verge of delivering a fatal blow to Moriarty's criminal organization, is forced to flee to continental Europe to escape Moriarty's retribution. The criminal mastermind follows, and the pursuit ends on top of the Reichenbach Falls, an encounter that apparently ends with both Holmes and Moriarty falling to their deaths. In this story, Moriarty is introduced as a criminal mastermind who protects nearly all of the criminals of England in exchange for their obedience and a share in their profits. Holmes, by his own account, was originally led to Moriarty by his perception that many of the crimes he investigated were not isolated incidents, but instead the machinations of a vast and subtle criminal organization.

In the same story, Holmes describes Moriarty's physical appearance to Watson. According to Holmes, Moriarty is extremely tall and thin, clean-shaven, pale, and ascetic-looking. He has a forehead that "domes out in a white curve", deeply sunken eyes, and shoulders that are "rounded from much study". His face protrudes forward and is always slowly oscillating from side to side "in a curiously reptilian fashion".[3]

Moriarty plays a direct role in only one other Holmes story, The Valley of Fear (1914), set before "The Final Problem" but written afterwards. In The Valley of Fear, Holmes attempts to prevent Moriarty's agents from committing a murder. In an episode in which Moriarty is being interviewed by a policeman, a painting by Jean-Baptiste Greuze is described as hanging on the wall; Holmes remarks on another work by the same painter to show it could not have been purchased on a professor's salary. The work referred to is La jeune fille à l'agneau;[4] some commentators[5] have described this as a pun by Doyle on the Thomas Agnew and Sons art gallery which had a famous Thomas Gainsborough painting, the Portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire[6] stolen by Adam Worth but were unable to prove the claim.[5]

Holmes mentions Moriarty reminiscently in five other stories: "The Adventure of the Empty House" (the immediate sequel to "The Final Problem"), "The Adventure of the Norwood Builder", "The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter", "The Adventure of the Illustrious Client", and "His Last Bow".

Doctor Watson, even when narrating, never meets Moriarty (only getting distant glimpses of him in "The Final Problem"), and relies upon Holmes to relate accounts of the detective's feud with the criminal. Doyle is inconsistent on Watson's familiarity with Moriarty. In "The Final Problem", Watson tells Holmes he has never heard of Moriarty, while in The Valley of Fear, set earlier on, Watson already knows of him as "the famous scientific criminal".

In "The Empty House", Holmes states that Moriarty had commissioned a powerful air gun from a blind German mechanic surnamed von Herder, which was used by Moriarty's employee/acolyte Colonel Moran. It closely resembled a cane, allowing for easy concealment, was capable of firing revolver bullets at long range, and made very little noise when fired, making it ideal for sniping. Moriarty also has a marked preference for organizing "accidents". His attempts to kill Holmes include falling masonry and a speeding horse-drawn vehicle. He is also responsible for stage-managing the death of Birdy Edwards, making it appear that he was lost overboard while sailing to South Africa.[7]

Personality

Moriarty is highly ruthless, shown by his steadfast vow to Sherlock Holmes that "if you are clever enough to bring destruction upon me, rest assured that I shall do as much to you".[8] Moriarty is categorised by Holmes as an extremely powerful criminal mastermind who is purely adept at committing any atrocity to perfection without losing any sleep over it. It is stated in "The Final Problem" that Moriarty does not directly participate in the activities he plans, but only orchestrates the events. What makes Moriarty so dangerous is his extremely cunning intellect:

He is a man of good birth and excellent education, endowed by nature with a phenomenal mathematical faculty. [...] But the man had hereditary tendencies of the most diabolical kind. A criminal strain ran in his blood, which, instead of being modified, was increased and rendered infinitely more dangerous by his extraordinary mental powers. [...] He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson. He is the organiser of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city...

— Holmes, "The Final Problem"

Holmes echoes and expounds this sentiment in The Valley of Fear stating:

The greatest schemer of all time, the organizer of every devilry, the controlling brain of the underworld, a brain which might have made or marred the destiny of nations—that's the man! But so aloof is he from general suspicion, so immune from criticism, so admirable in his management and self-effacement, that for those very words that you have uttered, he could hale you to a court and emerge with your year's pension as a solatium for his wounded character. [...] Foul-mouthed doctor and slandered professor—such would be your respective roles! That's genius, Watson.

— Holmes, The Valley of Fear

Moriarty has respect for Holmes's intelligence, stating that "It has been an intellectual treat for me to see the manner in which you [Holmes] have grappled with this case". Nevertheless, he makes numerous attempts upon Holmes's life through his agents. He shows a fiery disposition, becoming enraged when his plans are thwarted and he is placed "in positive danger of losing my liberty" as well as furiously elbowing aside passengers in the train station in his pursuit of the disguised Holmes. Moriarty also shows a fiercely independent streak, pursuing Holmes to Switzerland alone, while by contrast Holmes takes Watson with him everywhere he goes.

Doyle's original motive in creating Moriarty was evidently his intention to kill Holmes off.[9] "The Final Problem" was intended to be exactly what its title says; Doyle sought to sweeten the pill by letting Holmes go in a blaze of glory, having rid the world of a criminal so powerful and dangerous any further task would be trivial in comparison (as Holmes says in the story itself). Eventually, however, public pressure and financial troubles impelled Doyle to bring Holmes back.[10]

Moriarty's personal history

"Moriarty" is an ancient Irish name[11] as is Moran, the surname of Moriarty's henchman, Sebastian Moran.[12][13] Doyle himself was of Irish Catholic descent, educated at Stonyhurst College, although he abandoned his family's religious tradition, neither marrying nor raising his children in the Catholic faith, nor cleaving to any politics that his ethnic background might presuppose. Doyle is known to have used his experiences at Stonyhurst as inspiration for details of the Holmes series; among his contemporaries at the school were two boys surnamed Moriarty.[14]

At the age of twenty-one, Moriarty gained recognition for writing "a treatise upon the Binomial Theorem", which led to him being awarded the Mathematical Chair at one of England's smaller universities. Moriarty was also the author of a much respected work titled The Dynamics of an Asteroid. After he became the subject of unspecified "dark rumours" in the university town, he was compelled to resign his teaching post and he moved to London,[15] where he established himself as an "army coach", a private tutor to officers preparing for exams.[3]

The stories give contradictory indications about Moriarty's family. In his first appearance in "The Final Problem", Moriarty is referred to as "Professor Moriarty" — no forename is mentioned. Watson does, however, refer to the name of another family member when he writes of "the recent letters in which Colonel James Moriarty defends the memory of his brother". In "The Adventure of the Empty House", Holmes refers to Moriarty on one occasion as "Professor James Moriarty". This is the only time Moriarty is given a first name, and oddly, it is the same as that of his purported brother. In The Valley of Fear (written after the preceding two stories, but set earlier), Holmes says of Professor Moriarty: "He is unmarried. His younger brother is a station master in the west of England."[16] In Sherlock Holmes: A Drama in Four Acts, an 1899 stage play of which Doyle was a co-author, he is named Professor Robert Moriarty.[17]

Commentators have variously interpreted Professor Moriarty as having one brother (who is a colonel and station master)[3] or two brothers (one a colonel and the other a station master).[18] Vincent Starrett wrote that it is possible that Moriarty had one or two brothers, though Starrett considered two more likely, and suggested that all three brothers were named James.[1]

Multiple pastiches and other works outside of Doyle's stories purport to provide additional information about Moriarty's background. John F. Bowers, a lecturer in mathematics at the University of Leeds, wrote a tongue-in-cheek article in 1989 in which he assesses Moriarty's contributions to mathematics and gives a detailed description of Moriarty's background, including a statement that Moriarty was born in Ireland.[19][20] The 2005 pastiche novel Sherlock Holmes: The Unauthorized Biography also reports that Moriarty was born in Ireland, and states that he was employed as a professor by Durham University.[21] According to the 2020 audio drama Sherlock Holmes: The Voice of Treason, written by George Mann and Cavan Scott, Moriarty was a professor at Stonyhurst College (where Arthur Conan Doyle was educated).[22]

Real-world role models

ln addition to the master criminal Adam Worth, there has been much speculation among astronomers and Sherlock Holmes enthusiasts that Doyle based his fictional character Moriarty on the Canadian-American astronomer Simon Newcomb.[23] Newcomb was revered as a multitalented genius, with a special mastery of mathematics, and he had become internationally famous in the years before Doyle began writing his stories. More to the point, Newcomb had earned a reputation for spite and malice, apparently seeking to destroy the careers and reputations of rival scientists.[24]

Moriarty may have been inspired in part by two real-world mathematicians. If the characterisations of Moriarty's academic papers are reversed, they describe real mathematical events. Carl Friedrich Gauss wrote a famous paper on the dynamics of an asteroid[25] in his early 20s, and was appointed to a chair partly on the strength of this result. Srinivasa Ramanujan wrote about generalisations of the binomial theorem,[26] and earned a reputation as a genius by writing articles that confounded the best extant mathematicians.[27] Gauss's story was well known in Doyle's time, and Ramanujan's story unfolded at Cambridge from early 1913 to mid 1914;[28] The Valley of Fear, which contains the comment about maths so abstruse that no one could criticise it, was published in September 1914. Irish mathematician Des MacHale has suggested George Boole may have been a model for Moriarty.[29][30]

Jane Stanford, in That Irishman, suggests that Doyle borrowed some of the traits and background of the Fenian John O'Connor Power for his portrayal of Moriarty.[31] In Moriarty Unmasked: Conan Doyle and an Anglo-Irish Quarrel, 2017, Stanford explores Doyle's relationship with the Irish literary and political community in London. She suggests that Moriarty, Ireland's Napoleon, represents the Fenian threat at the heart of the British Empire. O'Connor Power studied at St Jarlath's Diocesan College in Tuam, County Galway. In his third and last year he was Professor of Humanities. As an ex-professor, the Fenian leader successfully made a bid for a Westminster seat in County Mayo.[32]

It is averred that surviving Jesuit priests at the preparatory school Hodder Place, Stonyhurst, instantly recognised the physical description of Moriarty as that of the Rev. Thomas Kay, SJ, Prefect of Discipline, under whose authority Doyle fell as a wayward pupil.[33] According to this hypothesis, Doyle as a private joke has Inspector MacDonald describe Moriarty: "He'd have made a grand meenister with his thin face and grey hair and his solemn-like way of talking."[34]

The model which Doyle himself cited (through Sherlock Holmes) in The Valley of Fear is the London arch-criminal of the 18th century, Jonathan Wild. He mentions this when seeking to compare Moriarty to a real-world character that Inspector Alec MacDonald might know, but it is in vain as MacDonald is not so well read as Holmes.

Legacy

T. S. Eliot's character Macavity the Mystery Cat is based on Moriarty.[35]

A Sherlockian society was formed by noted Sherlockian John Bennett Shaw[18] called "The Brothers Three of Moriarty", in honor of Professor Moriarty and his two brothers.[36] The group held annual dinners in Moriarty, New Mexico.[36]

Depictions

References

- Starrett, Vincent (2016). 221B: Studies in Sherlock Holmes (Reprinted ed.). Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 9781787201330.

- Klinger, Leslie (ed.). The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Volume I (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005). p. xxxv. ISBN 0-393-05916-2)

- Cawthorne, Nigel (201). A Brief History of Sherlock Holmes. Robinson. pp. 216–220. ISBN 978-0-7624-4408-3.

- "Girl With A Lamb".

- John Mortimer (24 August 1997). "To Catch a Thief". The New York Times.. A review of THE NAPOLEON OF CRIME — The Life and Times of Adam Worth, Master Thief by Ben Macintyre

- "A portrait of Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire by Thomas Gainsborough".

- Epilogue, The Valley of Fear.

- Doyle, Conan (1894). "The Adventure of the Final Problem". McClure's Magazine. Vol. 2. Astor Place, New York: J.J, Little and Co. p. 104. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Stashower, Daniel (1999). Teller of Tales: The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle. New York : Holt. p. 149. ISBN 978-0805050745.

- Miller, Ron. "Case Book: Doyle vs. Holmes". PBS.

- Daniel Jones; A.C. Gimson (1977). Everyman's English Pronouncing Dictionary (14 ed.). London, UK: J.M. Dent & Sons.

- Moran genealogy site; accessed 28 June 2014.

- Moran profile, irishgathering.ie; accessed 28 June 2014.

- Liukkonen, Petri. "Arthur Conan Doyle". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 11 January 2008.

- Smith, Daniel (2014) [2009]. The Sherlock Holmes Companion: An Elementary Guide (Updated ed.). London: Aurum Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1-84513-458-7.

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Sherlock Holmes: The Complete Novels and Stories, Volume 2. Random House., p. 175.

- "Sherlock Holmes, A Drama in Four Acts. ACT II".

- Boström, Mattias (2018). From Holmes to Sherlock. Mysterious Press. p. 386. ISBN 978-0-8021-2789-1.

- Bowers, John F. (23 December 1989). "James Moriarty: a forgotten mathematician". New Scientist. pp. 17–19.

- Arbesman, Samuel (2013). The Half-Life of Facts: Why Everything We Know Has an Expiration Date. Penguin. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9781591846512.

- Rennison, Nick (1 December 2007). Sherlock Holmes: The Unauthorized Biography. pp. 67–68. ISBN 9781555848736.

- Sherlock Holmes: The Voice of Treason (16 March 2020). Audible Original Drama (audiobook). "Chapter 7."

- Schaefer, B. E., 1993, Sherlock Holmes and some astronomical connections, Journal of the British Astronomical Association, vol 103, no. 1, pp. 30–34. For a summary of this point, see this New Scientist article, also from 1993.

- For example, see Newcomb's animosity to the career and works of Charles Peirce.

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1809). Theoria motus corporum coelestium in sectionibus conicis solem ambientium. Hamburg, Germany: Friedrich Perthes and I.H. Besser., as described in Donald Teets, Karen Whitehead, 1999 "The Discovery of Ceres: How Gauss Became Famous", Mathematics Magazine, vol 72, no 2 (April 1999), pp. 83–93

- "Ramanujan Psi Sum". Mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- Kanigel, R. (1991). The man who knew infinity: A life of the genius Ramanujan. Scribner. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-671-75061-9.

- See, for example, the book by Kanigel, The Man Who Knew Infinity

- MacHale, Desmond (1995). "George Boole and Sherlock Holmes". The Legacy of George Boole. Cork, Ireland.

- Lynch, Peter (15 November 2018). "Could Sherlock Holmes's true nemesis have been a mathematician?". The Irish Times. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- Stanford, Jane (2011). That Irishman: The Life and Times of John O'Connor Power. Dublin: The History Press, Ireland. pp. 30, 124–27. ISBN 978-1-84588-698-1.

- Moriarty Unmasked, p.28.

- "Letter from Stonyhurst achivist about Doyle's experience there" (PDF).

- The Valley of Fear, The Oxford Sherlock Holmes, p. 181

- Dundas, Zach (2015). The Great Detective. Mariner Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-544-70521-0.

- Boström, Mattias (2018). From Holmes to Sherlock. Mysterious Press. pp. 405–406. ISBN 978-0-8021-2789-1.

External links

- The Final Problem

- The Valley of Fear

- Sherlock Holmes Public Library

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Professor Moriarty", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.