Postpartum confinement

Postpartum confinement refers to a traditional practice following childbirth.[1] Those who follow these customs typically begin immediately after the birth, and the confinement lasts for a culturally variable length: typically for one month or 30 days,[2] up to 40 days, two months or 100 days.[3] This postnatal recuperation can include "traditional health beliefs, taboos, rituals, and proscriptions."[4] The practice used to be known as "lying-in", which, as the term suggests, centres around bed rest. In some cultures it may be connected to taboos concerning impurity after childbirth.

The custom is well-documented in China, where it is known as "Sitting the month". Japanese women know it as "Sango no hidachi" and Koreans as sanhujori, which means "recovery after giving birth". In Latin American countries it is called la cuarentena, i.e. "forty days" (a cognate with the English word "quarantine"). In India it is called jaappa (also transliterated japa); in Pakistan, sawa mahina ("five weeks").

Overview

Postpartum confinement refers both to the mother and the baby. Human newborns are so underdeveloped that pediatricians such as Harvey Karp refer to the first three months as the "fourth trimester".[5] The weeks of rest while the mother heals also protect the infant as it adjusts to the world, and both learn the skills of breastfeeding.

Almost all countries have some form of maternity leave. Many countries encourage men to take some paternity leave, but even those that mandate that some of the shared parental leave must be used by the father ("father's quota") acknowledge that the mother needs time off work to recover from the childbirth and deal with the postpartum physiological changes.

A 2016 American book describes the difficulties of documenting these "global grandmotherly customs" but asserts that "like a golden rope connecting women from one generation to the next, the protocol of caring for the new mother by unburdening her of responsibilities and ensuring she rests and eats shows up in wildly diverse places".[6] These customs have been documented in dozens of academic studies, and commonly include support for the new mother (including a release from household chores), rest, special foods to eat (and ones to avoid), specific hygiene practices, and ways of caring for the newborn.[7]

Martha Wolfenstein and Margaret Mead wrote in 1955 that the postpartum period meant a "woman can be cherished and pampered without feeling inadequate or shamed". The 2016 review that quoted them cites customs from around the world, from Biblical times to modern Greece:

From the data it seems that women were housebound for a number of days after the birth and the length of this period of seclusion varied by caste or ethnic group [in Nepal]. This is a phenomenon found across the globe, including in high-income countries in the recent past. The length of time a woman is secluded or rested varied across different countries and the principles underpinning this isolation (to heal vs. being unclean) also seem to differ greatly. After the period of seclusion there is often a ceremony to purify women to publicly accept them back into daily life. The literature supports the concept of a resting – a lengthy lie-in or lying-in period, a period of seclusion, as women need to rest in order to heal, yet it may mean that they are neglected.[8]

Health effects

One meta-review of studies concluded, "There is little consistent evidence that confinement practices reduce postpartum depression."[9]

China

"Sitting the month": 坐月子 "Zuò yuè zi" in Mandarin or 坐月 "Co5 Jyut2" in Cantonese. The custom, documented as far back as the year 960[10], is referred to as 'confinement' as women are advised to stay indoors for recovery from the trauma of birth and feed the newborn baby. Aspects of traditional Chinese medicine are included, with a special focus on eating foods considered to be nourishing for the body and help with the production of breastmilk. In Guangdong and neighboring regions, new mothers are barred from visitors until the baby is 12 days old, marked by a celebration called 'Twelve mornings' (known as 十二朝). From this day onwards, Cantonese families with a new baby usually share their joy through giving away food gifts, while some families mark the occasion by paying tribute to their ancestors.

In ancient China, women of certain ethnic groups in the South would resume work right after birth, and allow the men to practice postpartum confinement instead.[11] (See Couvade.)

Everyday habits and personal hygiene practices

During confinement, mothers are told not to expose their body to physical agents such cold weather or wind, as these are claimed to be detrimental to their recovery. Specifically, mothers were traditionally not allowed[12] to have any contact with water (e.g. bathing or washing hair), to exert themselves by climbing stairs, to read books or cry, to sew, or to have sex.

Nowadays, however, new mothers may wash their hair or take a bath or shower infrequently during the postpartum period, but it is claimed to be important to dry their body immediately afterwards with a clean towel and their hair properly using a hair dryer. It is also claimed to be important for women to wrap up warm and minimize the amount of skin exposed, as it was believed that they may catch a cold during this vulnerable time.

Special foods

The custom of confinement advises new mothers to choose energy and protein-rich foods to recover energy levels, help shrink the uterus and for the perineum to heal. This is also important for the production of breastmilk. Sometimes, new mothers only begin to consume special herbal foods after all the lochia is discharged.

A common dish is pork knuckles with ginger and black vinegar as pork knuckles are believed to help replenish calcium levels in the women. Ginger is featured in many dishes, as it is believed that it can remove the 'wind' accumulated in the body during pregnancy. Meat-based soup broths are also commonly consumed to provide hydration and added nutrients. Although not entirely backed by scientific evidence, for example, fish and papaya soup is considered to help produce breastmilk.[13]

Other East Asian countries

Other East Asian cultures have their own versions of "sitting the month", combining prescribed foods with proscribed activities.

Sanhujori is Korea's version of postnatal care. It draws on principles that emphasize activities and foods that keep the body warm, rest and relaxation to maximize the body’s return to its normal state, maintaining cleanliness, eating nutritious foods, and peace of mind and heart.[14] The resting itself is known as sam chil il.[15]

Thailand has various customs. New mothers used to be encouraged to lie in a warm bed near the fire for 30 days, a practice known as yu fai. This has been adapted into a form of Thai massage. Kao krachome is a type of herbal medicine in which the steam from the boiled plants is inhaled. Ya dong involves herbal medicine taken internally. Thai immigrants to Sweden report using the steam bath to heal after childbirth, although the correct ingredients are not easy to find.[16] Thai Australians who had had caesarian sections felt that they did not need to - in fact, ought not to - undergo these rituals.[17]

Indian subcontinent

Most traditional Indians follow the 40-day confinement and recuperation period also known as the jaappa (in Hindi). A special diet to facilitate milk production and increase hemoglobin levels is followed. Sex is not allowed during this time. In Hindu culture, this time after childbirth was traditionally considered a period of relative impurity (asaucham), and a period of confinement of 10–40 days (known as purudu) was recommended for the mother and the baby. During this period, she was exempted from usual household chores and religious rites. The father was purified by a ritual bath before visiting the mother in confinement.

In the event of a stillbirth, the period of impurity for both parents was 24 hours.[18]

Many Indian subcultures have their own traditions after birth. This birth period is called Virdi (Marathi), which lasts for 10 days after birth and includes complete abstinence from puja or temple visits.

In Pakistan, postpartum tradition is known as sawa mahina ("five weeks").[19]

Latin America

The cuarantena (literally, forty days, also meaning quarantine) is practised in parts of Latin America, and amongst immigrant communities in the United States.[20] It is described as "intergenerational family ritual that facilitated adaptation to parenthood", including some paternal role reversal.[21]

European cultures

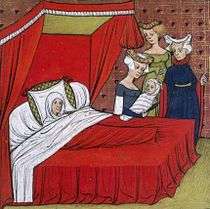

_A_Birth_Scene_(Desco_da_Parte)%2C_c._1410_Harvard_Art_museum_(2).jpg)

The term used in English, now old-fashioned or archaic, was once used to name maternity hospitals, for example the General Lying-In Hospital in London. A 1932 Canadian publication refers to lying-in as ranging from two weeks to two months.[22] These weeks ended with the re-introduction of the mother to the community in the Christian ceremony of the churching of women.

Lying-in features in Christian art, notably Birth of Jesus paintings. One of the gifts presented to the new mother in Renaisssance Florence was a desco da parto, a special form of painted tray. Equivalent presents in contemporary culture include baby showers and push presents.

Special foods included caudle, a restorative drink. "Taking caudle" was a metonym for postpartum social visits.

Modern commercial versions

Traditionally, women were taken care of by their elders: their mother, mother-in-law, sister, or aunt. The lying-in hospitals provided an institutional variation which gave women weeks of bedrest and a respite from household chores. Increasingly, these older women are unavailable or unwilling to take on this role; given the lingering effects of the one-child policy, many older Chinese women had limited experience of newborn babies, having only had one themselves. Replacements for this familial help are commercial services, both in the home and at residential centres.

At home

Agencies provide specialist carers that come to the new parents' home. This job used to be known as the monthly nurse, as she came and lived with the family for a month. Now more common terms are maternity nurse, newborn care specialist, or confinement nanny; the worker is not a registered health care professional such as the word "nurse" usually implies in current English. In Indian English the role is called a "japa maid".

A doula is best known as a birth companion, but some provide practical and emotional post-birth support. A lactation consultant and a health visitor are trained health professionals who may assist the new mother at this time. In the Netherlands, the in-home support is known as kraamzorg, and standard within the national health insurance system.

The use of yue sao, a specialist carer translated in Canada as "postpartum doula",[23] is also very common in China. Yue sao typically are live-in domestic helpers who care for both the new mother and baby for the first month after birth. Salaries as at 2017 vary from RMB8000 to RMB20000 per month depending on city and experience.[24] They are described as "mothering the mother".[25] Australian documentary-maker Aela Callan called them "Chinese supermums" but says they are colloquially known as "confinement ladies".[26]

Residential facilities

Companies have sprung up to offer extended postpartum care outside the home, sometimes in a hotel-like environment. Luxury options are a business.[27] Private postpartum care centres were introduced to Korea in 1996 under the name of sanhujoriwon.[28] Within the Chinese tradition, specialist businesses such as Red Wall Confinement Centre charge up to $27,000 for one month.[29] In Taiwan, postpartum nursing centres are popular, for those who can afford them.[30]

Birth tourism centres operating under the radar in the United States for Chinese women offer "sitting the month".[31]

See also

- Culture and menstruation

- Maternal bond and Attachment theory

- Menstrual taboo, including places and times of separation

- Impurity after childbirth

- Grandmother hypothesis

- Women-only space

- Wet nurse

- Parental investment in humans

- Sex after childbirth

References

- Withers, M; Kharazmi, N; Lim, E (January 2018). "Traditional beliefs and practices in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum: A review of the evidence from Asian countries". Midwifery. 56: 158–170. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2017.10.019. PMID 29132060.

- Chien, Yeh-Chung; Huang, Ya-Jing; Hsu, Chun-Sen; Chao, Jane C-J; Liu, Jen-Fang (2008). "Effect of Alcohol consumption on Maternal lactation characteristics during 'doing-the-month' ritual". Public Health Nutrition. 12 (3): 382–388. doi:10.1017/S1368980008002152. PMID 18426631.

- "Confinement practices: an overview". BabyCenter. Retrieved 2016-03-21.

- Tung, Wei-Chen (22 June 2010). "Doing the Month and Asian Cultures: Implications for Health Care". Home Health Care Management & Practice. 22 (5): 369–371. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1020.5139. doi:10.1177/1084822310367473.

- "Dr. Karp On Parenting And The Science Of Sleep". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Ou, Heng; Amely, Greeven; Belger, Marisa (2016). The First Forty Days: The Essential Art of Nourishing the New Mother. ISBN 9781617691836.

- Dennis, Cindy-Lee; Fung, Kenneth; Grigoriadis, Sophie; Robinson, Gail Erlick; Romans, Sarah; Ross, Lori (July 2007). "Traditional Postpartum Practices and Rituals: A Qualitative Systematic Review". Women's Health. 3 (4): 487–502. doi:10.2217/17455057.3.4.487. ISSN 1745-5065. PMID 19804024.

- Sharma, S; van Teijlingen, E; Hundley, V; Angell, C; Simkhada, P (2016). "Dirty and 40 days in the wilderness: Eliciting childbirth and postnatal cultural practices and beliefs in Nepal". BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 16 (1): 147. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0938-4. PMC 4933986. PMID 27381177.

- Wong, Josephine; Fisher, Jane (August 2009). "The role of traditional confinement practices in determining postpartum depression in women in Chinese cultures: A systematic review of the English language evidence". Journal of Affective Disorders. 116 (3): 161–169. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.002. PMID 19135261.

- Hsu Oh, Leslie (8 January 2017). "I tried the Chinese practice of 'sitting the month' after childbirth". Washington Post. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- 《太平廣記》卷四八三引尉遲樞的《南楚新聞》記載:"南方有獠婦,生子便起。其夫臥床褥,飲食皆如乳婦。"《马可·波罗游记》:"傣族妇女产子,洗后裹以襁褓,产妇立起工作,产妇之夫则抱子卧床四十日";《黔记》卷二:郎慈苗在咸宁州,其俗更异,妇人产子,必夫守房,不逾门户,弥月乃出。产妇则出入耕作,措饭食,以供夫乳儿,日无暇刻。"

- 坐月子能洗头吗?坐月子洗头对身体有什么影响?

- "Milk booster: fish and papaya soup". BabyCenter. Retrieved 2016-03-21.

- Kim, Jeongeun (March 2003). "Survey on the Programs of Sanhujori Centers in Korea as the Traditional Postpartum Care Facilities". Women & Health. 38 (2): 107–117. doi:10.1300/j013v38n02_08. ISSN 0363-0242. PMID 14655798.

- Dennis, Cindy-Lee; Fung, Kenneth; Grigoriadis, Sophie; Robinson, Gail Erlick; Romans, Sarah; Ross, Lori (July 2007). "Traditional Postpartum Practices and Rituals: A Qualitative Systematic Review". Women's Health. 3 (4): 487–502. doi:10.2217/17455057.3.4.487. ISSN 1745-5065. PMID 19804024.

- Pranee C. Lundberg (2007). Pieroni, Andrea; Vandebroek, Ina (eds.). Traveling cultures and plants : the ethnobiology and ethnopharmacy of migrations. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781845456795.

- Rice, Pranee Liamputtong; Naksook, Charin (October 1998). "Caesarean or vaginal birth: perceptions and experience of Thai women in Australian hospitals". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 22 (5): 604–608. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.1998.tb01446.x. ISSN 1753-6405. PMID 9744217.

- John Marshall / Jaya Tirtha Charan Dasa. "GUIDE TO RITUAL IMPURITY - What to do at the junctions of birth and death". Hknet.org.nz. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- Qamar, Azher Hameed (27 June 2017). "The Postpartum Tradition of Sawa Mahina in Rural Punjab, Pakistan". Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics. 11 (1): 127–150. doi:10.1515/jef-2017-0008. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Tuhus-Dubrow, Rebecca (11 April 2011). "Why Won't This New Mom Wash Her Hair?". Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Niska, Kathleen; Snyder, Mariah; Lia-Hoagberg, Betty (October 1998). "Family Ritual Facilitates Adaptation to Parenthood". Public Health Nursing. 15 (5): 329–337. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1446.1998.tb00357.x. PMID 9798420.

- Lying in by Jan Nusche quoting The Bride's Book — A Perpetual Guide for the Montreal Bride, published in 1932

- Quan, Douglas (January 15, 2017). "Underground industry serves moms who follow Chinese custom of 'sitting the month' after childbirth". National Post. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- "Yue Sao". Ayicheng. Archived from the original on 2017-10-13. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- "ownyourbirth". ownyourbirth. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "China's Supermums". News. SBS (Australian TV channel). Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "Where a new baby means relaxation". NewsComAu. 21 September 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Michiyo, Nomura (2016). "A Study on the Continuance and Variation of Korean Traditional Postnatal Care in a Modern Postpartum Care Center". The Korean Folklore Society. 63: 37–77. doi:10.21318/TKF.2016.05.63.37.

- Levin, Dan (October 2015). "Red Wall Confinement Centre". New York Times. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- Yeh, Yueh-Chen; St John, Winsome; Venturato, Lorraine (1 June 2016). "Inside a Postpartum Nursing Center: Tradition and Change". Asian Nursing Research. 10 (2): 94–99. doi:10.1016/j.anr.2016.03.001. ISSN 1976-1317. PMID 27349665.

- Ni, Ching-Ching (25 March 2011). "'Birthing tourism' center in San Gabriel shut down". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

Further reading

- The First Forty Days: The Essential Art of Nourishing the New Mother. By Heng Ou, 2016

- Zuo Yuezi: An American Mother's Guide to Chinese Postpartum Recovery. by Guang Ming Whitley