Mental health

Mental health is the level of psychological well-being or an absence of mental illness. It is the state of someone who is "functioning at a satisfactory level of emotional and behavioral adjustment".[1] From the perspectives of positive psychology or of holism, mental health may include an individual's ability to enjoy life and to create a balance between life activities and efforts to achieve psychological resilience.[2] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental health includes "subjective well-being, perceived self-efficacy, autonomy, competence, inter-generational dependence, and self-actualization of one's intellectual and emotional potential, among others".[3] The WHO further states that the well-being of an individual is encompassed in the realization of their abilities, coping with normal stresses of life, productive work, and contribution to their community.[4] Cultural differences, subjective assessments, and competing professional theories all affect how one defines "mental health".[3][5]

Mental health and mental illness

According to the U.K. Surgeon Journal (1999), mental health is the successful performance of the mental function resulting in productive activities, fulfilling relationships with other people, and providing the ability to adapt to change and cope with adversity. The term mental illness refers collectively to all diagnosable mental disorders—health conditions characterized by alterations in thinking, mood, or behavior associated with distress or impaired functioning.[6][7] Mental health and mental illness are two continuous concepts. People with optimal mental health can also have a mental illness, and people who have no mental illness can also have poor mental health.[8]

Mental health problems may arise due to stress, loneliness, depression, anxiety, relationship problems, death of a loved one, suicidal thoughts, grief, addiction, ADHD, self-harm, various mood disorders, or other mental illnesses of varying degrees, as well as learning disabilities.[9][10] Therapists, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, nurse practitioners, or family physicians can help manage mental illness with treatments such as therapy, counseling, or medication.

History

Early History

Globally in early history, mental illness was viewed as a religious matter. In ancient Greek, Roman, Egyptian, and Indian writings, mental illness was viewed as a personal issue and religious castigation. In the 5th century B.C., Hippocrates was the first pioneer to address mental illness through medication or adjustments in a patient’s environment. Although his work was greatly influential, views on religious punishment and demonic possession persisted through the Middle Ages.[11]

U.S. History

In the mid-19th century, William Sweetser was the first to coin the term mental hygiene, which can be seen as the precursor to contemporary approaches to work on promoting positive mental health.[12][13] Isaac Ray, the fourth president[14] of the American Psychiatric Association and one of its founders, further defined mental hygiene as "the art of preserving the mind against all incidents and influences calculated to deteriorate its qualities, impair its energies, or derange its movements".[13]

In American history, mentally ill patients were thought to be religiously punished. This response persisted through the 1700s, along with inhumane confinement and stigmatization of such individuals.[11] Dorothea Dix (1802–1887) was an important figure in the development of the "mental hygiene" movement. Dix was a school teacher who endeavored to help people with mental disorders and to expose the sub-standard conditions into which they were put.[15] This became known as the "mental hygiene movement".[15] Before this movement, it was not uncommon that people affected by mental illness would be considerably neglected, often left alone in deplorable conditions without sufficient clothing.[15] From 1840-1880, she won over the support of the federal government to set up over 30 state psychiatric hospitals; however, they were understaffed, under-resourced, and were accused of violating human rights.[11]

Emil Kraepelin in 1896 developed the taxonomy of mental disorders which has dominated the field for nearly 80 years. Later, the proposed disease model of abnormality was subjected to analysis and considered normality to be relative to the physical, geographical and cultural aspects of the defining group.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Clifford Beers founded "Mental Health America – National Committee for Mental Hygiene", after publication of his accounts as a patient in several lunatic asylums, A Mind That Found Itself, in 1908[16] and opened the first outpatient mental health clinic in the United States.[17]

The mental hygiene movement, similarly to the social hygiene movement, had at times been associated with advocating eugenics and sterilisation of those considered too mentally deficient to be assisted into productive work and contented family life.[18][19] In the post-WWII years, references to mental hygiene were gradually replaced by the term 'mental health' due to its positive aspect that evolves from the treatment of illness to preventive and promotive areas of healthcare.[20]

Marie Jahoda described six major, fundamental categories that can be used to categorize individuals who are mentally healthy. These include: a positive attitude towards the self, personal growth, integration, autonomy, a true perception of reality, and environmental mastery, which include adaptability and healthy interpersonal relationships.[21]

Deinstitutionalization / Transinstitutionalization

When state hospitals were accused of violating human right, advocates pushed for deinstitutionalization: the replacement of federal mental hospitals for community mental health services. The closure of state-provisioned psychiatric hospitals was enforced by the Community Mental Health Centers Act in 1963 that laid out terms in which only patients who posed an imminent danger to others or themselves could be admitted into state facilities.[22] This was seen as an improvement from previous conditions, however, there still remains a debate on the conditions of these community resources.

It has been proven that this transition was beneficial for many patients: there was an increase in overall satisfaction, better quality of life, more friendships between patients, and not too costly. This proved to be true only in the circumstance that treatment facilities that had enough funding for staff and equipment as well as proper management.[23] However, this idea is a polarizing issue. Critics of deinstitutionalization argue that poor living conditions prevailed, patients were lonely, and they did not acquire proper medical care in these treatment homes.[24] Additionally, patients that were moved from state psychiatric care to nursing and residential homes had deficits in crucial aspects of their treatment. Some cases result in the shift of care from health workers to patients’ families, where they do not have the proper funding or medical expertise to give proper care.[24] On the other hand, patients that are treated in community mental health centers lack sufficient cancer testing, vaccinations, or otherwise regular medical check ups.[24]

Other critics of state deinstitutionalization argue that this was simply a transition to “transinstitutionalization”, or the idea that prisons and state-provisioned hospitals are interdependent. In other words, patients become inmates. This draws on the Penrose Hypothesis of 1939, which theorized that there was an inverse relationship between prisons’ population size and number of psychiatric hospital beds.[25] This means that populations that require psychiatric mental care will transition between institutions, which in this case, includes state psychiatric hospitals and criminal justice systems. Thus, a decrease in available psychiatric hospital beds occurred at the same time as an increase in inmates.[25] Although some are skeptical that this is due to other external factors, others will reason this conclusion to a lack of empathy for the mentally ill. There is no argument in the social stigmatization of those with mental illnesses, they have been widely marginalized and discriminated against in society.[11] In this source, researchers analyze how most compensation prisoners (detainees who are unable or unwilling to pay a fine for petty crimes) are unemployed, homeless, and with an extraordinarily high degree of mental illnesses and substance abuse.[25] Compensation prisoners then lose prospective job opportunities, face social marginalization, and lack access to resocialization programs which ultimately facilitate reoffending.[25] The research sheds light on how the mentally ill — and in this case, the poor— are further punished for certain circumstances that are beyond their control, and that this is a vicious cycle that repeats itself. Thus, prisons embody another state-provisioned mental hospital.

Families of patients, advocates, and mental health professionals still call for the increase in more well-structured community facilities and treatment programs with a higher quality of long-term inpatient resources and care. With this more structured environment, the United States will continue with more access to mental health care and an increase in overall treatment of the mentally ill.

Significance

Mental illnesses are more common than cancer, diabetes, or heart disease. Over 26 percent of all Americans over the age of 18 meet the criteria for having a mental illness.[26] A World Health Organization (WHO) report estimates the global cost of mental illness at nearly $2.5 trillion (two-thirds in indirect costs) in 2010, with a projected increase to over $6 trillion by 2030.[27]

Evidence from the WHO suggests that nearly half of the world's population is affected by mental illness with an impact on their self-esteem, relationships and ability to function in everyday life.[28] An individual's emotional health can impact their physical health. Poor mental health can lead to problems such as the ability to make adequate decisions and substance abuse.[29]

Good mental health can improve life quality whereas poor mental health can worsen it. According to Richards, Campania, & Muse-Burke, "There is growing evidence that is showing emotional abilities are associated with pro-social behaviors such as stress management and physical health."[29] Their research also concluded that people who lack emotional expression are inclined to anti-social behaviors (e.g., drug and alcohol abuse, physical fights, vandalism), which reflects ones mental health and suppressed emotions.[29] Adults and children who face mental illness may experience social stigma, which can exacerbate the issues.[30]

Mental Health Youth Prevalence

According to 2020 data, mental illnesses are stagnant among adults, but rapidly deteriorated among the youth, categorized as 12 to 17 year olds.[31] To give insight on the severity of mental health in children, 13% of youth in America reported suffering from at least one Major Depressive Episode(MDE) in the past year, with the worst being 18% in Oregon.[31] Only 28% receive consistent treatment and 70% are left untreated.[31] In lower income communities, it is more common to forego treatment as a result of financial resources. Being left untreated also leads to unhealthy coping mechanisms such as substance abuse, which in turn causes its own host of mental health issues

Perspectives

Mental well-being

Mental health can be seen as an unstable continuum, where an individual's mental health may have many different possible values.[32] Mental wellness is generally viewed as a positive attribute, even if the person does not have any diagnosed mental health condition. This definition of mental health highlights emotional well-being, the capacity to live a full and creative life, and the flexibility to deal with life's inevitable challenges. Some discussions are formulated in terms of contentment or happiness.[33] Many therapeutic systems and self-help books offer methods and philosophies espousing strategies and techniques vaunted as effective for further improving the mental wellness. Positive psychology is increasingly prominent in mental health.

A holistic model of mental health generally includes concepts based upon anthropological, educational, psychological, religious, and sociological perspectives. There are also models as theoretical perspectives from personality, social, clinical, health and developmental psychology.[34][35]

The tripartite model of mental well-being[32][36] views mental well-being as encompassing three components of emotional well-being, social well-being, and psychological well-being. Emotional well-being is defined as having high levels of positive emotions, whereas social and psychological well-being are defined as the presence of psychological and social skills and abilities that contribute to optimal functioning in daily life. The model has received empirical support across cultures.[36][37][38] The Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) is the most widely used scale to measure the tripartite model of mental well-being.[39][40][41]

Children and young adults

Mental health and stability is a very important factor in a person's everyday life. The human brain develops many skills at an early age including social skills, behavioral skills, and one's way of thinking. Learning how to interact with others and how to focus on certain subjects are essential lessons to learn at a young age. This starts from the time we can talk all the way to when we are so old that we can barely walk. However, there are people in society who have difficulties with these skills and behave differently. A mental illness consist of a wide range of conditions that affects a person's mood, thinking, and behavior.[42] About 26% of people in the United States, ages 18 and older, have been diagnosed with some kind of mental disorder. However, not much is said about children with mental illnesses even though there are many that develop one, even as early as age three.

The most common mental illnesses in children include, but are not limited to anxiety disorder, as well as depression in older children and teens. Having a mental illness at a younger age is different from having one in adulthood. Children's brains are still developing and will continue to develop until around the age of twenty-five.[43] When a mental illness is thrown into the mix, it becomes significantly harder for a child to acquire the necessary skills and habits that people use throughout the day. For example, behavioral skills don't develop as fast as motor or sensory skills do.[43] So when a child has an anxiety disorder, they begin to lack proper social interaction and associate many ordinary things with intense fear.[44] This can be scary for the child because they don't necessarily understand why they act and think the way that they do. Many researchers say that parents should keep an eye on their child if they have any reason to believe that something is slightly off.[43] If the children are evaluated earlier, they become more acquainted to their disorder and treating it becomes part of their daily routine.[43] This is opposed to adults who might not recover as quickly because it is more difficult for them to adapt when already being accustomed in a certain direction of life.

Mental illness affects not only the person themselves, but the people around them. Friends and family also play an important role in the child's mental health stability and treatment.[45] If the child is young, parents are the ones who evaluate their child and decide whether or not they need some form of help.[46] Friends are a support system for the child and family as a whole. Living with a mental disorder is never easy, so it's always important to have people around to make the days a little easier. However, there are negative factors that come with the social aspect of mental illness as well. Parents are sometimes held responsible for their child's illness.[46] People also say that the parents raised their children in a certain way or they acquired their behavior from them. Family and friends are sometimes so ashamed of the idea of being close to someone with a disorder that the child feels isolated and thinks that they have to hide their illness from others.[46] When in reality, hiding it from people prevents the child from getting the right amount of social interaction and treatment in order to thrive in today's society.

Stigmas are also a well-known factor in mental illness. A stigma is defined as “a mark of disgrace associated with a particular circumstance, quality, or person.” Stigmas are used especially when it comes to the mentally disabled. People have this assumption that everyone with a mental problem, no matter how mild or severe, is automatically considered destructive or a criminal person. Thanks to the media, this idea has been planted in our brains from a young age.[47] Watching movies about teens with depression or children with autism makes us think that all of the people that have a mental illness are like the ones on TV. In reality, the media displays an exaggerated version of most illnesses. Unfortunately, not many people know that, so they continue to belittle those with disorders. In a recent study, a majority of young people associate mental illness with extreme sadness or violent tendencies .[48] Now that children are becoming more and more open to technology and the media itself, future generations will then continue to pair mental illness with negative thoughts. The media should be explaining that many people with psychiatric disorders like ADHD and anxiety, can live an ordinary life with the correct treatment and should not be punished for something they cannot help.

Sueki, (2013) carried out a study titled “The effect of suicide–related internet use on users’ mental health: A longitudinal Study”. This study investigated the effects of suicide-related internet use on user's suicidal thoughts, predisposition to depression and anxiety and loneliness. The study consisted of 850 internet users; the data was obtained by carrying out a questionnaire amongst the participants. This study found that browsing websites related to suicide, and methods used to commit suicide, had a negative effect on suicidal thoughts and increased depression and anxiety tendencies. The study concluded that as suicide-related internet use adversely affected the mental health of certain age groups it may be prudent to reduce or control their exposure to these websites. These findings certainly suggest that the internet can indeed have a profoundly negative impact on our mental health.[49]

Psychiatrist Thomas Szasz compared that 50 years ago children were either categorized as good or bad, and today "all children are good, but some are mentally healthy and others are mentally ill". The social control and forced identity creation is the cause of many mental health problems among today's children.[50] A behavior or misbehavior might not be an illness but exercise of their free will and today's immediacy in drug administration for every problem along with the legal over-guarding and regard of a child's status as a dependent shakes their personal self and invades their internal growth.

The Homeless

Mental health is not only prevalent among children and young adults, but also the homeless. it's evident that mental illness is impacting these people just as much as anybody. In an article written by Lisa Godman and her colleagues, they reference Smith’s research on the prevance of PTSD among homeless people. His research stated “ Homelessness itself is a risk factor for emotional disorder”. What this quote is saying is that being homeless itself can cause emotional disorder. Without looking for other reasons for emotional disorder and really looking at the simple fact that an individual is homeless can cause emotional disorder. Godman’s article stated “Recently, Smith ( 1991) investigated the prevalence of PTSD among a sample of 300 randomly selected homeless single women and mothers in St. Louis, Mis- souri. Using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS; Robins, 1981; Robins & Helzer, 1984), she found that 53% of the respondents could be diagnosed as exhibiting full-blown cases of PTSD”. As the source explains, the conclusion that was drawn from Smith’s investigation after studying 300 homeless individuals is that 53% of those people were eligible to be diagnosed with PTSD. She continues and states“ In addition, data from clinical observations, self-reports, and empirical studies suggest that at least two commonly reported symptoms of psychological trauma, social disaffiliation and learned helplessness are highly prevalent among homeless individuals and families.” Other datas were able to prove that PTSD and learned helplessness were two symptoms that were very much present among homeless individuals and families. The question would be how are these people being helped. This is evident that mental health among homeless is an issue existing but barely touched.[51] In another article by Stephen W. Hwang and Rochelle E Garner, they talk about the ways that the homeless are getting actually getting help. It states “For homeless people with mental illness, case management linked to other services was effective in improving psychiatric symptoms, and assertive case management was effective in decreasing psychiatric hospitalizations and increasing outpatient contacts. For homeless people with substance abuse problems, case management resulted in greater decreases in substance use than did usual care”. The question would be how are these people being helped. As the source explained, case management provided by services was helpful in improving psychiatric symptoms. It also caused a decrease in substance use than usual media care.[52]

Prevention

Mental health is conventionally defined as a hybrid of absence of a mental disorder and presence of well-being. Focus is increasing on preventing mental disorders. Prevention is beginning to appear in mental health strategies, including the 2004 WHO report "Prevention of Mental Disorders", the 2008 EU "Pact for Mental Health" and the 2011 US National Prevention Strategy.[53][54] Some commentators have argued that a pragmatic and practical approach to mental disorder prevention at work would be to treat it the same way as physical injury prevention.[55]

Prevention of a disorder at a young age may significantly decrease the chances that a child will suffer from a disorder later in life, and shall be the most efficient and effective measure from a public health perspective.[56] Prevention may require the regular consultation of a physician for at least twice a year to detect any signs that reveal any mental health concerns. Similar to mandated health screenings, bills across the U.S. are being introduced to require mental health screenings for students attending public schools. Supporters of these bills hope to diagnose mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression in order to prevent self-harm and any harm induced on other students.

Additionally, social media is becoming a resource for prevention. In 2004, the Mental Health Services Act[57] began to fund marketing initiatives to educate the public on mental health. This California-based project is working to combat the negative perception with mental health and reduce the stigma associated with it. While social media can benefit mental health, it can also lead to deterioration if not managed properly.[58] Limiting social media intake is beneficial .[59]

Cultural and religious considerations

Mental health is a socially constructed and socially defined concept; that is, different societies, groups, cultures, institutions and professions have very different ways of conceptualizing its nature and causes, determining what is mentally healthy, and deciding what interventions, if any, are appropriate.[60] Thus, different professionals will have different cultural, class, political and religious backgrounds, which will impact the methodology applied during treatment. In the context of deaf mental health care, it is necessary for professionals to have cultural competency of deaf and hard of hearing people and to understand how to properly rely on trained, qualified, and certified interpreters when working with culturally Deaf clients.

Research has shown that there is stigma attached to mental illness.[61] In the United Kingdom, the Royal College of Psychiatrists organized the campaign Changing Minds (1998–2003) to help reduce stigma.[62] Due to this stigma, individuals may resist 'labeling' or respond to mental health diagnoses with denialism.[63]

Family caregivers of individuals with mental disorders may also suffer discrimination or stigma.[64]

Addressing and eliminating the social stigma and perceived stigma attached to mental illness has been recognized as a crucial part to addressing the education of mental health issues. In the United States, the National Alliance of Mental Illness is an institution that was founded in 1979 to represent and advocate for victims struggling with mental health issues. NAMI also helps to educate about mental illnesses and health issues, while also working to eliminate the stigma[65] attached to these disorders such as anxiety and depression. Research has shown acts of discrimination and social stigma are associated with poorer mental health outcomes in racial (e.g. African Americans),[66][67][68] ethnic (e.g. Muslim women),[69] and sexual and gender minorities (e.g. transgender persons).[70][71]

Many mental health professionals are beginning to, or already understand, the importance of competency in religious diversity and spirituality. They are also partaking in cultural training in order to better understand which interventions work best for these different groups of people. The American Psychological Association explicitly states that religion must be respected. Education in spiritual and religious matters is also required by the American Psychiatric Association,[72] however, far less attention is paid to the damage that more rigid, fundamentalist faiths commonly practiced in the United States can cause.[73] This theme has been widely politicized in 2018 such as with the creation of the Religious Liberty Task Force in July of that year.[74] In addition, many providers and practitioners in the United States are only beginning to realize that the institution of mental healthcare lacks knowledge and competence of many non-Western cultures, leaving providers in the United States ill-equipped to treat patients from different cultures.[75]

Emotional improvement

Unemployment has been shown to have a negative impact on an individual's emotional well-being, self-esteem and more broadly their mental health. Increasing unemployment has been shown to have a significant impact on mental health, predominantly depressive disorders.[76] This is an important consideration when reviewing the triggers for mental health disorders in any population survey.[77] In order to improve your emotional mental health, the root of the issue has to be resolved. "Prevention emphasizes the avoidance of risk factors; promotion aims to enhance an individual's ability to achieve a positive sense of self-esteem, mastery, well-being, and social inclusion."[78] It is very important to improve your emotional mental health by surrounding yourself with positive relationships. We as humans, feed off companionships and interaction with other people. Another way to improve your emotional mental health is participating in activities that can allow you to relax and take time for yourself. Yoga is a great example of an activity that calms your entire body and nerves. According to a study on well-being by Richards, Campania and Muse-Burke, "mindfulness is considered to be a purposeful state, it may be that those who practice it believe in its importance and value being mindful, so that valuing of self-care activities may influence the intentional component of mindfulness."[29]

Care navigation

Mental health care navigation helps to guide patients and families through the fragmented, often confusing mental health industries. Care navigators work closely with patients and families through discussion and collaboration to provide information on best therapies as well as referrals to practitioners and facilities specializing in particular forms of emotional improvement. The difference between therapy and care navigation is that the care navigation process provides information and directs patients to therapy rather than providing therapy. Still, care navigators may offer diagnosis and treatment planning. Though many care navigators are also trained therapists and doctors. Care navigation is the link between the patient and the below therapies. A clear recognition that mental health requires medical intervention was demonstrated in a study by Kessler et al. of the prevalence and treatment of mental disorders from 1990 to 2003 in the United States. Despite the prevalence of mental health disorders remaining unchanged during this period, the number of patients seeking treatment for mental disorders increased threefold.[79]

Emotional issues

Emotional mental disorders are a leading cause of disabilities worldwide. Investigating the degree and severity of untreated emotional mental disorders throughout the world is a top priority of the World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative,[80] which was created in 1998 by the World Health Organization (WHO).[81] "Neuropsychiatric disorders are the leading causes of disability worldwide, accounting for 37% of all healthy life years lost through disease.These disorders are most destructive to low and middle-income countries due to their inability to provide their citizens with proper aid. Despite modern treatment and rehabilitation for emotional mental health disorders, "even economically advantaged societies have competing priorities and budgetary constraints".

The World Mental Health survey initiative has suggested a plan for countries to redesign their mental health care systems to best allocate resources. "A first step is documentation of services being used and the extent and nature of unmet needs for treatment. A second step could be to do a cross-national comparison of service use and unmet needs in countries with different mental health care systems. Such comparisons can help to uncover optimum financing, national policies, and delivery systems for mental health care."

Knowledge of how to provide effective emotional mental health care has become imperative worldwide. Unfortunately, most countries have insufficient data to guide decisions, absent or competing visions for resources, and near constant pressures to cut insurance and entitlements. WMH surveys were done in Africa (Nigeria, South Africa), the Americas (Colombia, Mexico, United States), Asia and the Pacific (Japan, New Zealand, Beijing and Shanghai in the People's Republic of China), Europe (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Ukraine), and the middle east (Israel, Lebanon). Countries were classified with World Bank criteria as low-income (Nigeria), lower middle-income (China, Colombia, South Africa, Ukraine), higher middle-income (Lebanon, Mexico), and high-income.

The coordinated surveys on emotional mental health disorders, their severity, and treatments were implemented in the aforementioned countries. These surveys assessed the frequency, types, and adequacy of mental health service use in 17 countries in which WMH surveys are complete. The WMH also examined unmet needs for treatment in strata defined by the seriousness of mental disorders. Their research showed that "the number of respondents using any 12-month mental health service was generally lower in developing than in developed countries, and the proportion receiving services tended to correspond to countries' percentages of gross domestic product spent on health care". "High levels of unmet need worldwide are not surprising, since WHO Project ATLAS' findings of much lower mental health expenditures than was suggested by the magnitude of burdens from mental illnesses. Generally, unmet needs in low-income and middle-income countries might be attributable to these nations spending reduced amounts (usually <1%) of already diminished health budgets on mental health care, and they rely heavily on out-of-pocket spending by citizens who are ill-equipped for it".

Treatment

Older methods of treatment

Trepanation

Archaeological records have shown that trepanation was a procedure used to treat "headaches, insanities or epilepsy" in several parts of the world in the Stone age. It was a surgical process used in the Stone Age. Paul Broca studied trepanation and came up with his own theory on it. He noticed that the fractures on the skulls dug up weren't caused by wounds inflicted due to violence, but because of careful surgical procedures. "Doctors used sharpened stones to scrape the skull and drill holes into the head of the patient" to allow evil spirits which plagued the patient to escape. There were several patients that died in these procedures, but those that survived were revered and believed to possess "properties of a mystical order".[82][83]

Lobotomy

Lobotomy was used in the 20th century as a common practice of alternative treatment for mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and depression. The first ever modern leucotomy meant for the purpose of treating a mental illness occurred in 1935 by a Portuguese neurologist, Antonio Egas Moniz. He received the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1949. . This belief that mental health illnesses could be treated by surgery came from Swiss neurologist, Gottlieb Burckhardt. After conducting experiments on six patients with schizophrenia, he claimed that half of his patients recovered or calmed down. Psychiatrist Walter Freeman believed that "an overload of emotions led to mental illness and “that cutting certain nerves in the brain could eliminate excess emotion and stabilize a personality", according to a National Public Radio article.[84]

Exorcisms

"Exorcism is the religious or spiritual practice of evicting demons or other spiritual entities from a person, or an area, they are believed to have possessed."

Mental health illnesses such as Huntington's Disease (HD), Tourette syndrome and schizophrenia were believed to be signs of possession by the Devil. This led to several mentally ill patients being subjected to exorcisms. This practice has been around for a long time, though decreasing steadily until it reached a low in the 18th century. It seldom occurred until the 20th century when the numbers rose due to the attention the media was giving to exorcisms. Different belief systems practice exorcisms in different ways.[85]

Modern methods of treatment

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy is therapy that uses pharmaceutical drugs. Pharmacotherapy is used in the treatment of mental illness through the use of antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and the use of elements such as lithium.

Physical activity

For some people, physical exercise can improve mental as well as physical health. Playing sports, walking, cycling or doing any form of physical activity trigger the production of various hormones, sometimes including endorphins, which can elevate a person's mood.[86]

Studies have shown that in some cases, physical activity can have the same impact as antidepressants when treating depression and anxiety.[87]

Moreover, cessation of physical exercise may have adverse effects on some mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety. This could lead to many different negative outcomes such as obesity, skewed body image, lower levels of certain hormones, and many more health risks associated with mental illnesses.[88]

Activity therapies

Activity therapies, also called recreation therapy and occupational therapy, promote healing through active engagement. Making crafts can be a part of occupational therapy. Walks can be a part of recreation therapy. In recent years colouring has been recognised as an activity which has been proven to significantly lower the levels of depressive symptoms and anxiety in many studies.[89]

Expressive therapies

Expressive therapies or creative arts therapies are a form of psychotherapy that involves the arts or art-making. These therapies include music therapy, art therapy, dance therapy, drama therapy, and poetry therapy. It has been proven that Music therapy is an effective way of helping people who suffer from a mental health disorder.[90]

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is the general term for scientific based treatment of mental health issues based on modern medicine. It includes a number of schools, such as gestalt therapy, psychoanalysis, cognitive behavioral therapy, transpersonal psychology/psychotherapy, and dialectical behavioral therapy. Group therapy involves any type of therapy that takes place in a setting involving multiple people. It can include psychodynamic groups, expressive therapy groups, support groups (including the Twelve-step program), problem-solving and psychoeducation groups.

Meditation

The practice of mindfulness meditation has several mental health benefits, such as bringing about reductions in depression, anxiety and stress.[91][92][93][94] Mindfulness meditation may also be effective in treating substance use disorders.[95][96] Further, mindfulness meditation appears to bring about favorable structural changes in the brain.[97][98][99]

The Heartfulness meditation program has proven to show significant improvements in the state of mind of health-care professionals.[100] A study posted on the US National Library of Medicine showed that these professionals of varied stress levels were able to improve their conditions after this meditation program was conducted. They benefited in aspects of burnouts and emotional wellness.

People with anxiety disorders participated in a stress-reduction program conducted by researchers from the Mental Health Service Line at the W.G. Hefner Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Salisbury, North Carolina. The participants practiced mindfulness meditation. After the study was over, it was concluded that the "mindfulness meditation training program can effectively reduce symptoms of anxiety and panic and can help maintain these reductions in patients with generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or panic disorder with agoraphobia."[101]

Spiritual counseling

Spiritual counselors meet with people in need to offer comfort and support and to help them gain a better understanding of their issues and develop a problem-solving relation with spirituality. These types of counselors deliver care based on spiritual, psychological and theological principles.[102]

Social work in mental health

Social work in mental health, also called psychiatric social work, is a process where an individual in a setting is helped to attain freedom from overlapping internal and external problems (social and economic situations, family and other relationships, the physical and organizational environment, psychiatric symptoms, etc.). It aims for harmony, quality of life, self-actualization and personal adaptation across all systems. Psychiatric social workers are mental health professionals that can assist patients and their family members in coping with both mental health issues and various economic or social problems caused by mental illness or psychiatric dysfunctions and to attain improved mental health and well-being. They are vital members of the treatment teams in Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences in hospitals. They are employed in both outpatient and inpatient settings of a hospital, nursing homes, state and local governments, substance abuse clinics, correctional facilities, health care services...etc.[103]

In the United States, social workers provide most of the mental health services. According to government sources, 60 percent of mental health professionals are clinically trained social workers, 10 percent are psychiatrists, 23 percent are psychologists, and 5 percent are psychiatric nurses.[104]

Mental health social workers in Japan have professional knowledge of health and welfare and skills essential for person's well-being. Their social work training enables them as a professional to carry out Consultation assistance for mental disabilities and their social reintegration; Consultation regarding the rehabilitation of the victims; Advice and guidance for post-discharge residence and re-employment after hospitalized care, for major life events in regular life, money and self-management and in other relevant matters in order to equip them to adapt in daily life. Social workers provide individual home visits for mentally ill and do welfare services available, with specialized training a range of procedural services are coordinated for home, workplace and school. In an administrative relationship, Psychiatric social workers provides consultation, leadership, conflict management and work direction. Psychiatric social workers who provides assessment and psychosocial interventions function as a clinician, counselor and municipal staff of the health centers.[105]

Roles and functions

Social workers play many roles in mental health settings, including those of case manager, advocate, administrator, and therapist. The major functions of a psychiatric social worker are promotion and prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation. Social workers may also practice:

- Counseling and psychotherapy

- Case management and support services

- Crisis intervention

- Psychoeducation

- Psychiatric rehabilitation and recovery

- Care coordination and monitoring

- Program management/administration

- Program, policy and resource development

- Research and evaluation

Psychiatric social workers conduct psychosocial assessments of the patients and work to enhance patient and family communications with the medical team members and ensure the inter-professional cordiality in the team to secure patients with the best possible care and to be active partners in their care planning. Depending upon the requirement, social workers are often involved in illness education, counseling and psychotherapy. In all areas, they are pivotal to the aftercare process to facilitate a careful transition back to family and community.[106]

History

United States

During the 1840s, Dorothea Lynde Dix, a retired Boston teacher who is considered the founder of the Mental Health Movement, began a crusade that would change the way people with mental disorders were viewed and treated. Dix was not a social worker; the profession was not established until after her death in 1887. However, her life and work were embraced by early psychiatric social workers, and she is considered one of the pioneers of psychiatric social work along with Elizabeth Horton, who in 1907 was the first psychiatric social worker in the New York hospital system, and others.[107][108] The early twentieth century was a time of progressive change in attitudes towards mental illness. Community Mental Health Centers Act was passed in 1963. This policy encouraged the deinstitutionalisation of people with mental illness. Later, mental health consumer movement came by 1980s. A consumer was defined as a person who has received or is currently receiving services for a psychiatric condition. People with mental disorders and their families became advocates for better care. Building public understanding and awareness through consumer advocacy helped bring mental illness and its treatment into mainstream medicine and social services.[109] In the 2000s focus was on Managed care movement which aimed at a health care delivery system to eliminate unnecessary and inappropriate care in order to reduce costs & Recovery movement in which by principle acknowledges that many people with serious mental illness spontaneously recover and others recover and improve with proper treatment.[110]

Role of social workers made an impact with 2003 invasion of Iraq and War in Afghanistan (2001–present) social workers worked out of the NATO hospital in Afghanistan and Iraq bases. They made visits to provide counseling services at forward operating bases. Twenty-two percent of the clients were diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, 17 percent with depression, and 7 percent with alcohol abuse.[111] In 2009, a high level of suicides was reached among active-duty soldiers: 160 confirmed or suspected Army suicides. In 2008, the Marine Corps had a record 52 suicides.[112] The stress of long and repeated deployments to war zones, the dangerous and confusing nature of both wars, wavering public support for the wars, and reduced troop morale have all contributed to the escalating mental health issues.[113] Military and civilian social workers are primary service providers in the veterans’ health care system.

Mental health services, is a loose network of services ranging from highly structured inpatient psychiatric units to informal support groups, where psychiatric social workers indulges in the diverse approaches in multiple settings along with other paraprofessional workers.

Canada

A role for psychiatric social workers was established early in Canada's history of service delivery in the field of population health. Native North Americans understood mental trouble as an indication of an individual who had lost their equilibrium with the sense of place and belonging in general, and with the rest of the group in particular. In native healing beliefs, health and mental health were inseparable, so similar combinations of natural and spiritual remedies were often employed to relieve both mental and physical illness. These communities and families greatly valued holistic approaches for preventive health care. Indigenous peoples in Canada have faced cultural oppression and social marginalization through the actions of European colonizers and their institutions since the earliest periods of contact. Culture contact brought with it many forms of depredation. Economic, political, and religious institutions of the European settlers all contributed to the displacement and oppression of indigenous people.[114]

The first officially recorded treatment practices were in 1714, when Quebec opened wards for the mentally ill. In the 1830s social services were active through charity organizations and church parishes (Social Gospel Movement). Asylums for the insane were opened in 1835 in Saint John and New Brunswick. In 1841 in Toronto, when care for the mentally ill became institutionally based. Canada became a self-governing dominion in 1867, retaining its ties to the British crown. During this period age of industrial capitalism began, which lead to a social and economic dislocation in many forms. By 1887 asylums were converted to hospitals and nurses and attendants were employed for the care of the mentally ill. The first social work training began at the University of Toronto in 1914. In 1918 Clarence Hincks & Clifford Beers founded the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene, which later became the Canadian Mental Health Association. In the 1930s Dr. Clarence Hincks promoted prevention and of treating sufferers of mental illness before they were incapacitated/early detection.

World War II profoundly affected attitudes towards mental health. The medical examinations of recruits revealed that thousands of apparently healthy adults suffered mental difficulties. This knowledge changed public attitudes towards mental health, and stimulated research into preventive measures and methods of treatment.[115] In 1951 Mental Health Week was introduced across Canada. For the first half of the twentieth century, with a period of deinstitutionalisation beginning in the late 1960s psychiatric social work succeeded to the current emphasis on community-based care, psychiatric social work focused beyond the medical model's aspects on individual diagnosis to identify and address social inequities and structural issues. In the 1980s Mental Health Act was amended to give consumers the right to choose treatment alternatives. Later the focus shifted to workforce mental health issues and environment.[116]

India

The earliest citing of mental disorders in India are from Vedic Era (2000 BC – AD 600).[117] Charaka Samhita, an ayurvedic textbook believed to be from 400–200 BC describes various factors of mental stability. It also has instructions regarding how to set up a care delivery system.[118] In the same era, Siddha was a medical system in south India. The great sage Agastya was one of the 18 siddhas contributing to a system of medicine. This system has included the Agastiyar Kirigai Nool, a compendium of psychiatric disorders and their recommended treatments.[119][120] In Atharva Veda too there are descriptions and resolutions about mental health afflictions. In the Mughal period Unani system of medicine was introduced by an Indian physician Unhammad in 1222.[121] The existing form of psychotherapy was known then as ilaj-i-nafsani in Unani medicine.

The 18th century was a very unstable period in Indian history, which contributed to psychological and social chaos in the Indian subcontinent. In 1745, lunatic asylums were developed in Bombay (Mumbai) followed by Calcutta (Kolkata) in 1784, and Madras (Chennai) in 1794. The need to establish hospitals became more acute, first to treat and manage Englishmen and Indian 'sepoys' (military men) employed by the British East India Company.[122][123] The First Lunacy Act (also called Act No. 36) that came into effect in 1858 was later modified by a committee appointed in Bengal in 1888. Later, the Indian Lunacy Act, 1912 was brought under this legislation. A rehabilitation programme was initiated between 1870s and 1890s for persons with mental illness at the Mysore Lunatic Asylum, and then an occupational therapy department was established during this period in almost each of the lunatic asylums. The programme in the asylum was called 'work therapy'. In this programme, persons with mental illness were involved in the field of agriculture for all activities. This programme is considered as the seed of origin of psychosocial rehabilitation in India.

Berkeley-Hill, superintendent of the European Hospital (now known as the Central Institute of Psychiatry (CIP), established in 1918), was deeply concerned about the improvement of mental hospitals in those days. The sustained efforts of Berkeley-Hill helped to raise the standard of treatment and care and he also persuaded the government to change the term 'asylum' to 'hospital' in 1920.[124] Techniques similar to the current token-economy were first started in 1920 and called by the name 'habit formation chart' at the CIP, Ranchi. In 1937, the first post of psychiatric social worker was created in the child guidance clinic run by the Dhorabji Tata School of Social Work (established in 1936), It is considered as the first documented evidence of social work practice in Indian mental health field.

After Independence in 1947, general hospital psychiatry units (GHPUs) were established to improve conditions in existing hospitals, while at the same time encouraging outpatient care through these units. In Amritsar Dr. Vidyasagar, instituted active involvement of families in the care of persons with mental illness. This was advanced practice ahead of its times regarding treatment and care. This methodology had a greater impact on social work practice in the mental health field especially in reducing the stigmatisation. In 1948 Gauri Rani Banerjee, trained in the United States, started a master's course in medical and psychiatric social work at the Dhorabji Tata School of Social Work (Now TISS). Later the first trained psychiatric social worker was appointed in 1949 at the adult psychiatry unit of Yervada mental hospital, Pune.

In various parts of the country, in mental health service settings, social workers were employed—in 1956 at a mental hospital in Amritsar, in 1958 at a child guidance clinic of the college of nursing, and in Delhi in 1960 at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences and in 1962 at the Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital. In 1960, the Madras Mental Hospital (Now Institute of Mental Health), employed social workers to bridge the gap between doctors and patients. In 1961 the social work post was created at the NIMHANS. In these settings they took care of the psychosocial aspect of treatment. This system enabled social service practices to have a stronger long-term impact on mental health care.[125]

In 1966 by the recommendation Mental Health Advisory Committee, Ministry of Health, Government of India, NIMHANS commenced Department of Psychiatric Social Work started and a two-year Postgraduate Diploma in Psychiatric Social Work was introduced in 1968. In 1978, the nomenclature of the course was changed to MPhil in Psychiatric Social Work. Subsequently, a PhD Programme was introduced. By the recommendations Mudaliar committee in 1962, Diploma in Psychiatric Social Work was started in 1970 at the European Mental Hospital at Ranchi (now CIP). The program was upgraded and other higher training courses were added subsequently.

A new initiative to integrate mental health with general health services started in 1975 in India. The Ministry of Health, Government of India formulated the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) and launched it in 1982. The same was reviewed in 1995 and based on that, the District Mental Health Program (DMHP) was launched in 1996 which sought to integrate mental health care with public health care.[126] This model has been implemented in all the states and currently there are 125 DMHP sites in India.

National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) in 1998 and 2008 carried out systematic, intensive and critical examinations of mental hospitals in India. This resulted in recognition of the human rights of the persons with mental illness by the NHRC. From the NHRC's report as part of the NMHP, funds were provided for upgrading the facilities of mental hospitals. As a result of the study, it was revealed that there were more positive changes in the decade until the joint report of NHRC and NIMHANS in 2008 compared to the last 50 years until 1998.[127] In 2016 Mental Health Care Bill was passed which ensures and legally entitles access to treatments with coverage from insurance, safeguarding dignity of the afflicted person, improving legal and healthcare access and allows for free medications.[128][129][130] In December 2016, Disabilities Act 1995 was repealed with Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act (RPWD), 2016 from the 2014 Bill which ensures benefits for a wider population with disabilities. The Bill before becoming an Act was pushed for amendments by stakeholders mainly against alarming clauses in the "Equality and Non discrimination" section that diminishes the power of the act and allows establishments to overlook or discriminate against persons with disabilities and against the general lack of directives that requires to ensure the proper implementation of the Act.[131][132]

Mental health in India is in its developing stages. There aren't enough professionals to support the demand. According to the Indian Psychiatric Society, there are around 9000 psychiatrists only in the country as of January 2019. Going by this figure, India has 0.75 Psychiatrists per 100,000 population, while the desirable number is anything above 3 Psychiatrists per 100,000. While the number of psychiatrists has increased since 2010, it is still far from a healthy ratio.[133]

Lack of any universally accepted single licensing authority compared to foreign countries puts social workers at general in risk. But general bodies/councils accepts automatically a university-qualified social worker as a professional licensed to practice or as a qualified clinician. Lack of a centralized council in tie-up with Schools of Social Work also makes a decline in promotion for the scope of social workers as mental health professionals. Though in this midst the service of social workers has given a facelift to the mental health sector in the country with other allied professionals.

Prevalence and programs

Evidence suggests that 450 million people worldwide have some mental illness. Major depression ranks fourth among the top 10 leading causes of disease worldwide. By 2029, mental illness is predicted to become the leading cause of disease worldwide. Women are more likely to have a mental illness than men. One million people commit suicide every year and 10 to 20 million attempt it.[134]

Africa

Mental illnesses and mental health disorders are widespread concerns among underdeveloped African countries, yet these issues are largely neglected, as mental health care in Africa is given statistically less attention than it is in other, westernized nations. Rising death tolls due to mental illness demonstrate the imperative need for improved mental health care policies and advances in treatment for Africans suffering from psychological disorders.

Underdeveloped African countries are so visibly troubled by physical illnesses, disease, malnutrition, and contamination that the dilemma of lacking mental health care has not been prioritized, makes it challenging to have a recognized impact on the African population. In 1988 and 1990, two original resolutions were implemented by the World Health Organization's Member States in Africa. AFR/RC39/R1 and AFR/RC40/R9 attempted to improve the status of mental health care in specific African regions to combat its growing effects on the African people.[135] However, it was found that these new policies had little impact on the status of mental health in Africa, ultimately resulting in an incline in psychological disorders instead of the desired decline, and causing this to seem like an impossible problem to manage.

In Africa, there are many socio-cultural and biological factors that have led to heightened psychological struggles, while also masking their immediate level of importance to the African eye. Increasing rates of unemployment, violence, crime, rape, and disease are often linked to substance abuse, which can cause mental illness rates to inflate.[136] Additionally, physical disease like HIV/AIDS, the Ebola epidemic, and malaria often have lasting psychological effects on victims that go unrecognized in African communities because of their inherent cultural beliefs. Traditional African beliefs have led to the perception of mental illness as being caused by supernatural forces, preventing helpful or rational responses to abnormal behavior. For example, Ebola received loads of media attention when it became rampant in Africa and eventually spread to the US, however, researchers never really paid attention to its psychological effects on the African brain. Extreme anxiety, struggles with grief, feelings of rejection and incompetence, depression leading to suicide, PTSD, and much more are only some of the noted effects of diseases like Ebola.[137] These epidemics come and go, but their lasting effects on mental health are remaining for years to come, and even ending lives because of the lack of action. There has been some effort to financially fund psychiatric support in countries like Liberia, due to its dramatic mental health crisis after warfare, but not much was benefited. Aside from financial reasons, it is so difficult to enforce mental health interventions and manage mental health in general in underdeveloped countries simply because the individuals living there do not necessarily believe in western psychiatry. It is also important to note that the socio-cultural model of psychology and abnormal behavior is dependent on factors surrounding cultural differences.[138] This causes mental health abnormalities to remain more hidden due to the culture's natural behavior, compared to westernized behavior and cultural norms.

This relationship between mental and physical illness is an ongoing cycle that has yet to be broken. While there are many organizations attempting to solve problems pertaining to physical health in Africa, as these problems are clearly visible and recognizable, there is little action taken to confront the underlying mental effects that are left on the victims. It is recognized that many of the mentally ill in Africa search for help from spiritual or religious leaders, however this is widely due to the fact that many African countries are significantly lacking in mental health professionals in comparison to the rest of the world. In Ethiopia alone, there are “only 10 psychiatrists for the population of 61 million people,”[135] studies have shown. While numbers have definitely changed since this research was done, the lack of psychological professionals throughout African continues with a current average of 1.4 mental health workers per 100,000 people compared to the global statistic of 9.0 professionals per 100,00 people.[139] Additionally, statistics show that the “global annual rate of visits to mental health outpatient facilities is 1,051 per 100,000 population,” while “in Africa the rate is 14 per 100,000” visits. About half of Africa's countries have some sort of mental health policy, however, these policies are highly disregarded,[136] as Africa's government spends “less than 1% of the total health budget on mental health”.[140] Specifically in Sierra Leone, about 98.8% of people suffering from mental disorders remain untreated, even after the building of a well below average psychiatric hospital, further demonstrating the need for intervention.[139]

Not only has there been little hands-on action taken to combat mental health issues in Africa, but there has also been little research done on the topic to spread its awareness and prevent deaths. The Lancet Global Health[140] acknowledges that there are well over 1,000 published articles covering physical health in Africa, but there are still less than 50 discussing mental health. And this pressing dilemma of prioritizing physical health vs. mental health is only worsening as the continent's population is substantially growing with research showing that “Between 2000 and 2015 the continent's population grew by 49%, yet the number of years lost to disability as a result of mental and substance use disorders increased by 52%”.[139] The number of deaths caused by mental instability is truly competing with those caused by physical diseases: “In 2015, 17.9 million years were lost to disability as a consequence of mental health problems. Such disorders were almost as important a cause of years lost to disability as were infectious and parasitic diseases, which accounted for 18.5 million years lost to disability,”.[139] Mental health and physical health care, while they may seem separate, are very much connected, as these two factors determine life or death for humans. As new challenges surface and old challenges still haven't been prioritized, Africa's mental health care policies need significant improvement in order to provide its people with the appropriate health care they deserve, hopefully preventing this problem from expanding.

Australia

A survey conducted by Australian Bureau of Statistics in 2008 regarding adults with manageable to severe neurosis reveals almost half of the population had a mental disorder at some point of their life and one in five people had a sustained disorder in the preceding 12 months. In neurotic disorders, 14% of the population experienced anxiety and comorbidity disorders were next to common mental disorder with vulnerability to substance abuse and relapses. There were distinct gender differences in disposition to mental health illness. Women were found to have high rate of mental health disorders, and Men had higher propensity of risk for substance abuse. The SMHWB survey showed families that had low socioeconomic status and high dysfunctional patterns had a greater proportional risk for mental health disorders. A 2010 survey regarding adults with psychosis revealed 5 persons per 1000 in the population seeks professional mental health services for psychotic disorders and the most common psychotic disorder was schizophrenia.[141][142]

Canada

According to statistics released by the Centre of Addiction and Mental Health one in five people in Canada experience a mental health or addiction problem.[143] Young people ages 15 to 25 are particularly vulnerable. Major depression is found to affect 8% and anxiety disorder 12% of the population. Women are 1.5 times more likely to suffer from mood and anxiety disorders. WHO points out that there are distinct gender differences in patterns of mental health and illness.[144] The lack of power and control over their socioeconomic status, gender based violence; low social position and responsibility for the care of others render women vulnerable to mental health risks. Since more women than men seek help regarding a mental health problem, this has led to not only gender stereotyping but also reinforcing social stigma. WHO has found that this stereotyping has led doctors to diagnose depression more often in women than in men even when they display identical symptoms. Often communication between health care providers and women is authoritarian leading to either the under-treatment or over-treatment of these women.[4]

Organizations

Women's College Hospital has a program called the "Women's Mental Health Program" where doctors and nurses help treat and educate women regarding mental health collaboratively, individually, and online by answering questions from the public.[145]

Another Canadian organization serving mental health needs is the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). CAMH is one of Canada's largest and most well-known health and addiction facilities, and it has received international recognitions from the Pan American Health Organization and World Health Organization Collaborating Centre. They do research in areas of addiction and mental health in both men and women. In order to help both men and women, CAMH provides "clinical care, research, education, policy development and health promotion to help transform the lives of people affected by mental health and addiction issues."[146] CAMH is different from Women's College Hospital due to its widely known rehab centre for women who have minor addiction issues, to severe ones. This organization provides care for mental health issues by assessments, interventions, residential programs, treatments, and doctor and family support.[146]

Israel

In Israel, a Mental Health Insurance Reform took effect in July 2015, transferring responsibility for the provision of mental health services from the Ministry of Health to the four national health plans. Physical and mental health care were united under one roof; previously they had functioned separately in terms of finance, location, and provider. Under the reform, the health plans developed new services or expanded existing ones to address mental health problems.[147]

United States

According to the World Health Organization in 2004, depression is the leading cause of disability in the United States for individuals ages 15 to 44.[148] Absence from work in the U.S. due to depression is estimated to be in excess of $31 billion per year. Depression frequently co-occurs with a variety of medical illnesses such as heart disease, cancer, and chronic pain and is associated with poorer health status and prognosis.[149] Each year, roughly 30,000 Americans take their lives, while hundreds of thousands make suicide attempts (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).[150] In 2004, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), third among individuals ages 15–24. Despite the increasingly availability of effectual depression treatment, the level of unmet need for treatment remains high. By way of comparison, a study conducted in Australia during 2006 to 2007 reported that one-third (34.9%) of patients diagnosed with a mental health disorder had presented to medical health services for treatment.[151]

There are many factors that influence mental health including:

- Mental illness, disability, and suicide are ultimately the result of a combination of biology, environment, and access to and utilization of mental health treatment.

- Public health policies can influence access and utilization, which subsequently may improve mental health and help to progress the negative consequences of depression and its associated disability.

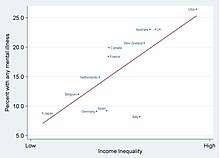

Emotional mental illnesses should be a particular concern in the United States since the U.S. has the highest annual prevalence rates (26 percent) for mental illnesses among a comparison of 14 developing and developed countries.[152] While approximately 80 percent of all people in the United States with a mental disorder eventually receive some form of treatment, on the average persons do not access care until nearly a decade following the development of their illness, and less than one-third of people who seek help receive minimally adequate care.[153] The government offers everyone programs and services, but veterans receive the most help, there is certain eligibility criteria that has to be met.[154]

Policies

The mental health policies in the United States have experienced four major reforms: the American asylum movement led by Dorothea Dix in 1843; the "mental hygiene" movement inspired by Clifford Beers in 1908; the deinstitutionalization started by Action for Mental Health in 1961; and the community support movement called for by The CMCH Act Amendments of 1975.[155]

In 1843, Dorothea Dix submitted a Memorial to the Legislature of Massachusetts, describing the abusive treatment and horrible conditions received by the mentally ill patients in jails, cages, and almshouses. She revealed in her Memorial: "I proceed, gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of insane persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience...."[156] Many asylums were built in that period, with high fences or walls separating the patients from other community members and strict rules regarding the entrance and exit. In those asylums, traditional treatments were well implemented: drugs were not used as a cure for a disease, but a way to reset equilibrium in a person's body, along with other essential elements such as healthy diets, fresh air, middle class culture, and the visits by their neighboring residents. In 1866, a recommendation came to the New York State Legislature to establish a separate asylum for chronic mentally ill patients. Some hospitals placed the chronic patients into separate wings or wards, or different buildings.[157]

In A Mind That Found Itself (1908) Clifford Whittingham Beers described the humiliating treatment he received and the deplorable conditions in the mental hospital.[158] One year later, the National Committee for Mental Hygiene (NCMH) was founded by a small group of reform-minded scholars and scientists – including Beers himself – which marked the beginning of the "mental hygiene" movement. The movement emphasized the importance of childhood prevention. World War I catalyzed this idea with an additional emphasis on the impact of maladjustment, which convinced the hygienists that prevention was the only practical approach to handle mental health issues.[159] However, prevention was not successful, especially for chronic illness; the condemnable conditions in the hospitals were even more prevalent, especially under the pressure of the increasing number of chronically ill and the influence of the depression.[155]

In 1961, the Joint Commission on Mental Health published a report called Action for Mental Health, whose goal was for community clinic care to take on the burden of prevention and early intervention of the mental illness, therefore to leave space in the hospitals for severe and chronic patients. The court started to rule in favor of the patients' will on whether they should be forced to treatment. By 1977, 650 community mental health centers were built to cover 43 percent of the population and serve 1.9 million individuals a year, and the lengths of treatment decreased from 6 months to only 23 days.[160] However, issues still existed. Due to inflation, especially in the 1970s, the community nursing homes received less money to support the care and treatment provided. Fewer than half of the planned centers were created, and new methods did not fully replace the old approaches to carry out its full capacity of treating power.[160] Besides, the community helping system was not fully established to support the patients' housing, vocational opportunities, income supports, and other benefits.[155] Many patients returned to welfare and criminal justice institutions, and more became homeless. The movement of deinstitutionalization was facing great challenges.[161]

After realizing that simply changing the location of mental health care from the state hospitals to nursing houses was insufficient to implement the idea of deinstitutionalization, the National Institute of Mental Health in 1975 created the Community Support Program (CSP) to provide funds for communities to set up a comprehensive mental health service and supports to help the mentally ill patients integrate successfully in the society. The program stressed the importance of other supports in addition to medical care, including housing, living expenses, employment, transportation, and education; and set up new national priority for people with serious mental disorders. In addition, the Congress enacted the Mental Health Systems Act of 1980 to prioritize the service to the mentally ill and emphasize the expansion of services beyond just clinical care alone.[162] Later in the 1980s, under the influence from the Congress and the Supreme Court, many programs started to help the patients regain their benefits. A new Medicaid service was also established to serve people who were diagnosed with a "chronic mental illness." People who were temporally hospitalized were also provided aid and care and a pre-release program was created to enable people to apply for reinstatement prior to discharge.[160] Not until 1990, around 35 years after the start of the deinstitutionalization, did the first state hospital begin to close. The number of hospitals dropped from around 300 by over 40 in the 1990s, and finally a Report on Mental Health showed the efficacy of mental health treatment, giving a range of treatments available for patients to choose.[162]

However, several critics maintain that deinstitutionalization has, from a mental health point of view, been a thoroughgoing failure. The seriously mentally ill are either homeless, or in prison; in either case (especially the latter), they are getting little or no mental health care. This failure is attributed to a number of reasons over which there is some degree of contention, although there is general agreement that community support programs have been ineffective at best, due to a lack of funding.[161]

The 2011 National Prevention Strategy included mental and emotional well-being, with recommendations including better parenting and early intervention programs, which increase the likelihood of prevention programs being included in future US mental health policies.[53] The NIMH is researching only suicide and HIV/AIDS prevention, but the National Prevention Strategy could lead to it focusing more broadly on longitudinal prevention studies.[163]

In 2013, United States Representative Tim Murphy introduced the Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act, HR2646. The bipartisan bill went through substantial revision and was reintroduced in 2015 by Murphy and Congresswoman Eddie Bernice Johnson. In November 2015, it passed the Health Subcommittee by an 18–12 vote.

See also

- Mental disability (disambiguation)

- Ethnopsychopharmacology

- Mental environment

- Reason

- Sanity

- Technology and mental health issues

- World Mental Health Day

Related disciplines and specialties

- Homelessness and mental health

- Infant mental health

- Information ecology

- Mental health first aid

- Mental health law

- Mental health of refugee children

- Self-help groups for mental health

- Youth health

Mental health in different occupations and regions

- Mental health in aviation

- Category:Mental health by country

- Mental health in Southeast Africa

- Mental health in the Middle East

- Mental health in Ghana

References

- "mental health". WordNet Search. Princeton university. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Snyder, C. R; Lopez, Shane J; Pedrotti, Jennifer Teramoto (2011). Positive psychology: the scientific and practical explorations of human strengths. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-8195-8. OCLC 639574840.

- "The world health report 2001 – Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope" (PDF). WHO. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- "Mental health: strengthening our response". World Health Organization. August 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- "Mental Health". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 2011

- "Mental Disorders". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- "What is Mental Health and Mental Illness? | Workplace Mental Health Promotion". Workplace Mental Health Promotion.

- "Practicing Effective Prevention". Center for the Application of Prevention Technologies. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 11 January 2016. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- Kitchener, Betty; Jorm, Anthony (2002). Mental Health First Aid Manual (1st ed.). Canberra: Center for Mental Health Research, Australian National University. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7315-4891-0. OCLC 62228904.

- "A Brief History of Mental Illness and the U.S. Mental Health Care System". www.uniteforsight.org. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- Shook, John R., ed. (April 2012). "Sweetser, William". Dictionary of Early American Philosophers. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 1016–1020. ISBN 978-1-4411-7140-5.

- Mandell, Wallace (1995). "Origins of Mental Health, The Realization of an Idea". Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Isaac Ray Award". www.psychiatry.org. American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved 27 October 2017.