Pokémon Red and Blue

Pokémon Red Version and Pokémon Blue Version are role-playing video games developed by Game Freak and published by Nintendo for the Game Boy. They are the first installments of the Pokémon video game series. They were first released in Japan in 1996 as Pocket Monsters: Red[lower-alpha 2] and Pocket Monsters: Green,[lower-alpha 3] with the special edition Pocket Monsters: Blue[lower-alpha 4] being released in Japan later that same year. The games were later released as Pokémon Red and Pokémon Blue in North America and Australia in 1998 and Europe in 1999.

| |

|---|---|

.webp.png) | |

| Developer(s) | Game Freak |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | Satoshi Tajiri |

| Producer(s) |

|

| Designer(s) | Satoshi Tajiri |

| Programmer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) |

|

| Writer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | Junichi Masuda |

| Series | Pokémon |

| Platform(s) | Game Boy |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

Pokémon Yellow, a special edition version, was released in Japan in 1998 and in other regions in 1999 and 2000. Remakes of Pokémon Red and Green for the Game Boy Advance, Pokémon FireRed and LeafGreen, were released in 2004. Pokémon Red, Blue, and Yellow (in addition to Green in Japan) were re-released on the Nintendo 3DS Virtual Console service as a commemoration of the franchise's 20th anniversary in 2016.

The player controls the protagonist from an overhead perspective and navigates him throughout the fictional region of Kanto in a quest to master Pokémon battling. The goal of the games is to become the champion of the Indigo League by defeating the eight Gym Leaders and then the top four Pokémon trainers in the land, the Elite Four. Another objective is to complete the Pokédex, an in-game encyclopedia, by obtaining the 150 available Pokémon. Red and Blue utilize the Game Link Cable, which connects two Game Boy systems together and allows Pokémon to be traded or battled between games. Both titles are independent of each other but feature the same plot,[1] and while they can be played separately, it is necessary for players to trade between both games in order to obtain all of the original 150 Pokémon.

Red and Blue were well-received with critics praising the multiplayer options, especially the concept of trading. They received an aggregated score of 89% on GameRankings and are considered among the greatest games ever made, perennially ranked on top game lists including at least four years on IGN's "Top 100 Games of All Time". The games' releases marked the beginning of what would become a multibillion-dollar franchise, jointly selling over 300 million copies worldwide. In 2009 they appeared in the Guinness Book of World Records under "Best selling RPG on the Game Boy" and "Best selling RPG of all time".

Gameplay

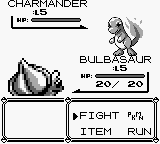

Pokémon Red and Blue are played in a third-person view, overhead perspective and consist of three basic screens: an overworld, in which the player navigates the main character;[2] a side-view battle screen;[3] and a menu interface, in which the player configures his or her Pokémon, items, or gameplay settings.[4]

The player can use his or her Pokémon to battle other Pokémon. When the player encounters a wild Pokémon or is challenged by a trainer, the screen switches to a turn-based battle screen that displays the engaged Pokémon. During a battle, the player may select a maneuver for his or her Pokémon to fight using one of four moves, use an item, switch his or her active Pokémon, or attempt to flee (the last of these is not possible in trainer battles). Pokémon have hit points (HP); when a Pokémon's HP is reduced to zero, it faints and can no longer battle until it is revived. Once an enemy Pokémon faints, the player's Pokémon involved in the battle receive a certain number of experience points (EXP). After accumulating enough EXP, a Pokémon will level up.[3] A Pokémon's level controls its physical properties, such as the battle statistics acquired, and the moves it has learned. At certain levels, the Pokémon may also evolve. These evolutions affect the statistics and the levels at which new moves are learned (higher levels of evolution gain more statistics per level, although they may not learn new moves as early, if at all, compared with the lower levels of evolution).[5]

Catching Pokémon is another essential element of the gameplay. While battling with a wild Pokémon, the player may throw a Poké Ball at it. If the Pokémon is successfully caught, it will come under the player's ownership. Factors in the success rate of capture include the HP of the target Pokémon and the type of Poké Ball used: the lower the target's HP and the stronger the Poké Ball, the higher the success rate of capture.[6] The ultimate goal of the games is to complete the entries in the Pokédex, a comprehensive Pokémon encyclopedia, by capturing, evolving, and trading to obtain all 151 creatures.[7]

Pokémon Red and Blue allow players to trade Pokémon between two cartridges via a Game Link Cable.[8] This method of trading must be done to fully complete the Pokédex since certain Pokémon will only evolve upon being traded and each of the two games have version-exclusive Pokémon.[1] The Link Cable also makes it possible to battle another player's Pokémon team.[8] When playing Red or Blue on a Game Boy Advance or SP, the standard GBA/SP link cable will not work; players must use the Nintendo Universal Game Link Cable instead.[9] Moreover, the English versions of the games are incompatible with their Japanese counterparts, and such trades will corrupt the save files, as the games use different languages and therefore character sets.[10]

As well as trading with each other and Pokémon Yellow, Pokémon Red and Blue can trade Pokémon with the second generation of Pokémon games: Pokémon Gold, Silver, and Crystal. However, there are limitations: the games cannot link together if one player's party contains Pokémon or moves introduced in the second generation games.[11] Also, using the Transfer Pak for the Nintendo 64, data such as Pokémon and items from Pokémon Red and Blue can be used in the Nintendo 64 games Pokémon Stadium[12] and Pokémon Stadium 2.[13] Red and Blue are incompatible with the Pokémon games of the later "Advanced Generation" for the Game Boy Advance and GameCube.[14]

Plot

Setting

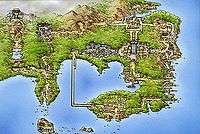

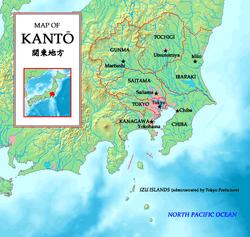

Pokémon Red and Blue take place in the region of Kanto, which is based on the real-life Kantō region in Japan. This is one distinct region, as shown in later games, with different geographical habitats for the 151 existing Pokémon species, along with human-populated towns and cities and Routes connecting locations with one another. Some areas are only accessible once the player learns a special ability or gains a special item.[15] Kanto has multiple locations: Pallet Town, Viridian City (トキワシティ Tokiwa City), Pewter City (ニビシティ Nibi City), Cerulean City (ハナダシティ Hanada City), Vermillion City (クチバシティ Kuchiba City), Lavender Town, Celadon City (タマムシシティ Tamamushi City), Fuchsia City (セキチクシティ Sekichiku City), Saffron City (ヤマブキシティ Yamabuki City), Cinnabar Island (グレンじま Guren Island), Seafoam Islands (ふたごじま Twin Islands) and the Indigo Plateau. Each city has a gym leader, serving as the boss and the Elite Four and final rival battle occur at Indigo Plateau. Areas in which the player can catch Pokémon range from caves to the sea, where the kinds of Pokémon available to catch varies. For example, Tentacool can only be caught either through fishing or when the player is in a body of water, while Zubat can only be caught in a cave.

Story

The player begins in their hometown of Pallet Town. After venturing alone into the tall grass, the player is stopped by Professor Oak, a famous Pokémon researcher. Professor Oak explains to the player that wild Pokémon may be living there and encountering them alone can be very dangerous.[16] He takes the player to his laboratory where the player meets Oak's grandson, a rival aspiring Pokémon Trainer. The player and the rival are both instructed to select a starter Pokémon for their travels out of Bulbasaur, Squirtle and Charmander.[17] Oak's Grandson will always choose the Pokémon which is stronger against the player's starting Pokémon. He will then challenge the player to a Pokémon battle with their newly obtained Pokémon and will continue to battle the player at certain points throughout the games.[18]

While visiting the region's cities, the player will encounter special establishments called Gyms. Inside these buildings are Gym Leaders, each of whom the player must defeat in a Pokémon battle to obtain a total of eight Gym Badges. Once the badges are acquired, the player is given permission to enter the Indigo League, which consists of the best Pokémon trainers in the region. There the player will battle the Elite Four and finally the new Champion: the player's rival.[19] Also, throughout the game, the player will have to battle against the forces of Team Rocket, a criminal organization that abuses Pokémon.[5] They devise numerous plans for stealing rare Pokémon, which the player must foil.[20][21]

Development

The concept of the Pokémon saga stems from the hobby of insect collecting, a popular pastime which game designer Satoshi Tajiri enjoyed as a child.[22] While growing up, however, he observed more urbanization taking place in the town where he lived and as a result, the insect population declined. Tajiri noticed that kids now played in their homes instead of outside and he came up with the idea of a video game, containing creatures that resembled insects, called Pokémon. He thought kids could relate with the Pokémon by individually naming them, and then controlling them to represent fear or anger as a good way of relieving stress. However, Pokémon never bleed nor die in battle, only faint – this was a very touchy subject to Tajiri, as he did not want to further fill the gaming world with "pointless violence".[23]

When the Game Boy was released, Tajiri thought the system was perfect for his idea, especially because of the link cable, which he envisioned would allow players to trade Pokémon with each other. This concept of trading information was new to the video gaming industry because previously connection cables were only being used for competition.[24] "I imagined a chunk of information being transferred by connecting two Game Boys with special cables, and I went wow, that's really going to be something!" said Tajiri.[25] Tajiri was also influenced by Square's Game Boy game The Final Fantasy Legend, noting in an interview that the game gave him the idea that more than just action games could be developed for the handheld.[26]

The main characters were named after Tajiri himself as Satoshi, who is described as Tajiri in his youth, and his long-time friend, role model, mentor, and fellow Nintendo developer; Shigeru Miyamoto as Shigeru.[23][27] Ken Sugimori, an artist and longtime friend of Tajiri, headed the development of drawings and designs of the Pokémon, working with a team of fewer than ten people who conceived the various designs for all 151 Pokémon. Sugimori, in turn, finalized each design, drawing the Pokémon from various angles in order to assist Game Freak's graphics department in properly rendering the creature.[28][29] Music for the game was composed by Junichi Masuda, who utilized the four sound channels of the Game Boy to create both the melodies and the sound effects and Pokémon "cries" heard upon encountering them. He noted the game's opening theme, titled "Monster", was produced with the image of battle scenes in mind, using white noise to sound like marching music and imitate a snare drum.[30]

Originally called Capsule Monsters, the game's title went through several transitions due to trademark difficulties, becoming CapuMon and KapuMon before eventually settling upon Pocket Monsters.[31][32] Tajiri always thought that Nintendo would reject his game, as the company did not really understand the concept at first. However, the games turned out to be a complete success, something Tajiri and Nintendo never expected, especially because of the declining popularity of the Game Boy.[23] Upon hearing of the Pokémon concept, Miyamoto suggested creating multiple cartridges with different Pokémon in each, noting it would assist the trading aspect.[33]

Release

In Japan, Pocket Monsters: Red and Green were the first versions released, having been completed by October 1995 and officially released on February 27, 1996. They sold rapidly, due in part to Nintendo's idea of producing the two versions of the game instead of a single title, prompting consumers to buy both.[25] Several months later, the Blue version was released in Japan as a mail-order-only special edition,[36] featuring updated in-game artwork and new dialogue.[37] To create more hype and challenge to the games, Tajiri revealed an extra Pokémon called Mew hidden within the games, which he believed "created a lot of rumors and myths about the game" and "kept the interest alive".[23] The creature was originally added by Shigeki Morimoto as an internal prank and wasn't supposed to be exposed to consumers.[38] It was not until later that Nintendo decided to distribute Mew through a Nintendo promotional event. However, in 2003 a glitch became widely known and could be exploited so anyone could obtain the elusive Pokémon.[39]

During the North American localization of Pokémon, a small team led by Hiro Nakamura went through the individual Pokémon, renaming them for western audiences based on their appearance and characteristics after approval from Nintendo Co. Ltd. In addition, during this process, Nintendo trademarked the 151 Pokémon names in order to ensure they would be unique to the franchise.[40] During the translation process, it became apparent that simply altering the games' text from Japanese to English was impossible; the games had to be entirely reprogrammed from scratch due to the fragile state of their source code, a side effect of the unusually lengthy development time.[29] Therefore, the games were based on the more modern Japanese version of Blue; modeling its programming and artwork, but keeping the same distribution of Pokémon found in the Japanese Red and Green cartridges, respectively.[36]

As the finished Red and Blue versions were being prepared for release, Nintendo allegedly spent over 50 million dollars to promote the games, fearing the series would not be appealing to American children.[41] The western localization team warned that the "cute monsters" may not be accepted by American audiences, and instead recommended they be redesigned and "beefed-up". Then-president of Nintendo Hiroshi Yamauchi refused and instead viewed the games' possible reception in America as a challenge to face.[42] Despite these setbacks, the reprogrammed Red and Blue versions with their original creature designs were eventually released in North America over two and a half years after Red and Green debuted in Japan, in September 28, 1998.[43][44] The games were received extremely well by the foreign audiences and Pokémon went on to become a lucrative franchise in America.[42] The same versions were later released in Europe in October 5, 1999.[45][46]

Re-releases

Pocket Monsters: Blue

Pocket Monsters: Blue[lower-alpha 5] was released in Japan as a mail-order-only special edition[36] to subscribers of CoroCoro Comic on October 15, 1996. It was later released to general retail on October 10, 1999.[47][48][49][50] The game featured updated in-game artwork and new dialogue.[37] Using Blastoise as its mascot, the code, script, and artwork for Blue were used for the international releases of Red and Green, which were renamed to Red and Blue.[36] The Japanese Blue edition of the game features all but a handful of Pokémon available in Red and Green, making certain Pokémon exclusive to the original editions.

Pokémon Yellow

Pokémon Yellow Version: Special Pikachu Edition,[lower-alpha 6] more commonly known as Pokémon Yellow Version, is an enhanced version of Red and Blue, and was originally released on September 12, 1998, in Japan,[51][52] with releases in North America and Europe on October 1, 1999,[53] and June 16, 2000,[54] respectively. The game was designed to resemble the Pokémon anime series, with the player receiving a Pikachu as his starter Pokémon, and his rival starting with an Eevee. Some non-player characters resemble those from the anime, including Team Rocket's Jessie and James.

Virtual Console

During the November 12, 2015, Nintendo Direct presentation, it was announced that the original generation of Pokémon games would be released for the Nintendo 3DS Virtual Console service on February 27, 2016, the 20th anniversary of the games' original Japanese release. The games include a first for the Virtual Console: simulated Link Cable functionality to allow trading and battling between games.[55] As was the case with its original release, Green is exclusive to Japanese consumers.[56] These versions of the games are able to transfer Pokémon to Pokémon Sun and Moon via the Pokémon Bank application.[57]

There was a special Nintendo 2DS bundle with each console matching the corresponding color of the game version; it was released in Japan, Europe, and Australia on February 27, 2016.[58] North America received a special New Nintendo 3DS bundle with cover plates styled after Red and Blue's box art.[59]

By March 31, 2016, combined sales of the re-releases reached 1.5 million units with more than half being sold in the American market.[60]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

The games received mostly positive reviews from critics, holding an aggregate score of 88% on GameRankings.[61] Special praise was given to its multiplayer features: the ability to trade and battle Pokémon with one another. Craig Harris of IGN gave the games a "masterful" 10 out of 10, noting that: "Even if you finish the quest, you still might not have all the Pokémon in the game. The challenge to catch 'em all is truly the game's biggest draw". He also commented on the popularity of the game, especially among children, describing it as a "craze".[1] GameSpot's Peter Bartholow, who gave the games a "great" 8.8 out of 10, cited the graphics and audio as somewhat primitive but stated that these were the games' only drawbacks. He praised the titles' replay value due to their customization and variety, and commented upon their universal appeal: "Under its cuddly exterior, Pokémon is a serious and unique RPG with lots of depth and excellent multiplayer extensions. As an RPG, the game is accessible enough for newcomers to the genre to enjoy, but it will entertain hard-core fans as well. It's easily one of the best Game Boy games to date".[5]

The success of these games has been attributed to their innovative gaming experience rather than audiovisual effects. Papers published by the Columbia Business School indicate both American and Japanese children prefer the actual gameplay of a game over special audio or visual effects. In Pokémon games, the lack of these artificial effects has actually been said to promote the child's imagination and creativity.[66] "With all the talk of game engines and texture mapping and so on, there is something refreshing about this superlative gameplay which makes you ignore the cutesy 8-bit graphics" commented The Guardian.[67]

During the 2nd Annual AIAS Interactive Achievement Awards (now known as the D.I.C.E. Awards), Pokémon Red and Blue won the award for "Outstanding Achievement in Character or Story Development", along with nominations for "Console Role-Playing Game of the Year" and "Outstanding Achievement in Interactive Design".[68]

Sales

Pokémon Red and Blue set the precedent for what has become a blockbuster, multibillion-dollar franchise.[69] Red, Green, and Blue sold 1.04 million units combined in Japan during 1996, and another 3.65 million in 1997. The latter performance made Pokémon, collectively, the country's best-selling game of the year, surpassing Final Fantasy VII.[70] The Pokémon games combined ultimately sold 10.23 million copies in Japan.[71] By the end of its run, it had sold a total combined sale of 9.85 million in the United States.[72] The games worldwide sales have reached over 31 million copies sold.[73][74] In 2009, IGN referred to Pokémon Red and Blue as the "Best selling RPG on the Game Boy" and "Best selling RPG of all time".[75]

Legacy

The video gaming website 1UP.com composed a list of the "Top 5 'Late to the Party' Games" showing selected titles that "prove a gaming platform's untapped potential" and were one of the last games released for their respective console. Red and Blue were ranked first and called Nintendo's "secret weapon" when the games were brought out for the Game Boy in the late 1990s.[25] Nintendo Power listed the Red and Blue versions together as the third best video game for the Game Boy and Game Boy Color, stating that something about the games kept them playing until they caught every Pokémon.[76] Game Informer's Ben Reeves called them (along with Pokémon Yellow, Gold, Silver, and Crystal) the second best Game Boy games and stated that it had more depth than it appeared.[77] Official Nintendo Magazine named the games one of the best Nintendo games of all time, placing 52nd on their list of the top 100 games.[78] Red and Blue made number 72 on IGN's "Top 100 Games of All Time" in 2003, in which the reviewers noted that the pair of games "started a revolution" and praised the deep game design and complex strategy, as well the option to trade between other games.[79] Two years later, it climbed the ranks to number 70 in the updated list, with the games' legacy again noted to have inspired multiple video game sequels, movies, television shows, and other merchandise, strongly rooting it in popular culture.[80] In 2007, Red and Blue were ranked at number 37 on the list, and the reviewers remarked at the games' longevity:

For everything that has come in the decade since, it all started right here with Pokémon Red/Blue''. Its unique blend of exploration, training, battling and trading created a game that was far more in-depth than it first appeared and one that actually forced the player to socialize with others in order to truly experience all that it had to offer. The game is long, engrossing and sparkles with that intangible addictiveness that only the best titles are able to capture. Say what you will about the game, but few gaming franchises can claim to be this popular ten years after they first hit store shelves.[27]

The games are widely credited with starting and helping pave the way for the successful multibillion-dollar series.[25] Five years after Red and Blue's initial release, Nintendo celebrated its "Pokémoniversary". George Harrison, the senior vice president of marketing and corporate communications of Nintendo of America, stated that "those precious gems [Pokémon Red and Blue] have evolved into Ruby and Sapphire. The release of Pokémon Pinball kicks off a line of great new Pokémon adventures that will be introduced in the coming months".[81] The series has since sold over 300 million games, all accredited to the enormous success of the original Red and Blue versions.[25][82]

On February 12, 2014, an anonymous Australian programmer launched Twitch Plays Pokémon, a "social experiment" on the video streaming website Twitch. The project was a crowdsourced attempt to play a modified version of Pokémon Red by typing commands into the channel's chat log, with an average of 50,000 viewers participating at the same time. The result was compared to "watching a car crash in slow motion".[83] The game was completed on March 1, 2014, boasting 390 hours of multi-user controlled non-stop gameplay.[84]

Remakes

Pokémon FireRed Version[lower-alpha 7] and Pokémon LeafGreen Version[lower-alpha 8] are enhanced remakes of Pokémon Red and Green. The new titles were developed by Game Freak and published by Nintendo for the Game Boy Advance and have compatibility with the Game Boy Advance Wireless Adapter, which originally came bundled with the games. However, due to the new variables added to FireRed and LeafGreen (such as changing the single, "Special" stat into two separate "Special Attack" and "Special Defense" stats), these titles are not compatible with older versions. FireRed and LeafGreen were first released in Japan on January 29, 2004,[85][86] and released in North America and Europe on September 9[87] and October 1, 2004[88] respectively. Nearly two years after their original release, Nintendo re-marketed them as Player's Choice titles.[89]

The games received critical acclaim, obtaining an aggregate score of 81 percent on Metacritic.[90] Most critics praised the fact that the games introduced new features while still maintaining the traditional gameplay of the series. Reception of the graphics and audio was more mixed, with some reviewers complaining that they were too simplistic and not much of an improvement over the previous games, Pokémon Ruby and Sapphire. FireRed and LeafGreen were commercial successes, selling a total of around 12 million copies worldwide.[91]

Notes

- Pokémon Blue Version was released in Japan as a mail-order-only special edition to subscribers of CoroCoro Comic on October 15, 1996. It was later released to general retail on October 10, 1999.

- Japanese: ポケットモンスター 赤 Hepburn: Poketto Monsutā Aka

- Japanese: ポケットモンスター 緑 Hepburn: Poketto Monsutā Midori

- Japanese: ポケットモンスター 青 Hepburn: Poketto Monsutā Ao

- ポケットモンスター 青 Poketto Monsutā Ao

- ポケットモンスターピカチュウ Poketto Monsutā Pikachū, lit. "Pocket Monsters: Pikachu"

- ポケットモンスター ファイアレッド Poketto Monsutā Faiareddo, lit. "Pocket Monsters: FireRed"

- ポケットモンスター リーフグリーン Poketto Monsutā Rīfugurīn, lit. "Pocket Monsters: LeafGreen"

References

- Harris, Craig (23 June 1999). "Pokemon Red Version Review". IGN. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- Game Freak (9 December 1997). Pokémon Red and Blue, Instruction manual. Nintendo. p. 8.

- Game Freak (30 September 1998). Pokémon Red and Blue, Instruction manual. Nintendo. p. 17.

- Game Freak (30 September 1998). Pokémon Red and Blue, Instruction manual. Nintendo. p. 10.

- Bartholow, Peter (28 January 2000). "GameSpot review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 6 February 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- Game Freak (30 September 1998). Pokémon Red and Blue, Instruction manual. Nintendo. p. 21.

- Game Freak (30 September 1998). Pokémon Red and Blue, Instruction manual. Nintendo. p. 7.

- Game Freak (30 September 1998). Pokémon Red and Blue, Instruction manual. Nintendo. p. 36.

- "nintendo.com.au – GBC – Frequently Asked Questions". Nintendo. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- "Game Boy Game Pak Troubleshooting – Specific Games". Nintendo of America Inc. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

MissingNO is a programming quirk, and not a real part of the game

- "Pokemon Gold and Silver Strategy Guide: Trading". IGN. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- Gerstmann, Jeff (29 February 2000). "Pokemon Stadium for Nintendo 64 Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- Villoria, Gerald (26 March 2001). "Pokemon Stadium 2 for Nintendo 64 Review". GameSpot. p. 2. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- Harris, Craig (17 March 2003). "IGN: Pokemon Ruby Version Review". IGN. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- Game Freak (30 September 1998). Pokémon Red and Blue, Instruction manual. Nintendo. p. 20.

- Game Freak (30 September 1998). Pokémon Red and Blue, Instruction manual. Nintendo. p. 2.

- Game Freak (30 September 1998). Pokémon Red and Blue, Instruction manual. Nintendo. p. 3.

- IGN Staff. "Guides: Pokemon: Blue and Red". IGN. p. 113. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- IGN Staff. "Guides: Pokemon: Blue and Red". IGN. p. 67. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- IGN Staff. "Guides: Pokemon: Blue and Red". IGN. p. 99. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- IGN Staff. "Guides: Pokemon: Blue and Red". IGN. p. 165. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- Plaza, Amadeo (6 February 2006). "A Salute to Japanese Game Designers". Amped IGO. p. 2. Archived from the original on 26 January 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2006.

- Larimer, Time (22 November 1999). "The Ultimate Game Freak". TIME Asia. p. 2. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- Larimer, Time (22 November 1999). "The Ultimate Game Freak". TIME Asia. p. 1. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- 1UP Staff. "Best Games to Come Out Late in a System's Life". 1UP. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- "Pokémon interview" (in Japanese). Nintendo. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games 2007 | 37 Pokemon Blue Version". IGN. Archived from the original on 22 May 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- Staff. "2. 一新されたポケモンの世界". Nintendo.com (in Japanese). Nintendo. p. 2. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- Kohler, Chris (2004). Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life (1st ed.). BradyGames. pp. 237–250. ISBN 0-7440-0424-1.

- Masuda, Junichi (28 February 2009). "HIDDEN POWER of Masuda: No. 125". Game Freak. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- Staff (18 February 2004). 写真で綴るレベルX~完全保存版! (in Japanese). AllAbout.co.jp. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- Tomisawa, Akihito (August 2000). ゲームフリーク 遊びの世界標準を塗り替えるクリエイティブ集団 (in Japanese). ISBN 4-8401-0118-3.

- Nutt, Christian (3 April 2009). "The Art of Balance: Pokémon's Masuda on Complexity and Simplicity". Gamasutra. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- "GB Pokémon Complete Sound CD". VGMdb. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- Hanson, Ben (13 May 2014). "Pokémon's Music Master: The Man Behind The Catchiest Songs". Game Informer. Archived from the original on 16 May 2014.

- Staff (November 1999). "What's the Deal with Pokémon?". Electronic Gaming Monthly (124): 216.

- Chen, Charlotte (December 1999). "Pokémon Report". Tips & Tricks. Larry Flynt Publications: 111.

- "Iwata Asks – Pokémon HeartGold Version & SoulSilver Version". Nintendo.com. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- DeVries, Jack (24 November 2008). "IGN: Pokemon Report: OMG Hacks". IGN. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- Staff (November 1999). "What's the Deal with Pokémon?". Electronic Gaming Monthly (124): 172.

- Tobin, Joseph Jay (2004). Pikachu's Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon. Duke University Press. p. 66. ISBN 0-8223-3287-6.

- Ashcraft, Brian (18 May 2009). "Pokemon Could Have Been Muscular Monsters". Kotaku. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- IGN Staff. "Guides: Pokemon: Blue and Red". IGN. p. 62. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- "Game Boy's Pokémon Unleashed on September 28!". Redmond, Washington: Nintendo. 28 September 1998. Archived from the original on 1 May 1999. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Pokémon Red Version". Nintendo of Europe. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "Pokémon Blue Version". Nintendo of Europe. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "ポケットモンスター 赤・緑". The Pokémon Company. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "ポケットモンスター赤・緑". Nintendo. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "ポケットモンスター 青". The Pokémon Company. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "ポケットモンスター青". Nintendo. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "ポケットモンスター イエロー". The Pokémon Company. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "ポケットモンスター イエロー". Nintendo. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Pokémon™ Yellow Special Pikachu Edition". The Pokémon Company International. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Pokémon™ Yellow Special Pikachu Edition". The Pokémon Company International. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Nintendo Direct - 11.12.2015". Nintendo. 12 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- "Nintendo Direct 2015.5.31 プレゼンテーション映像". Nintendo. 12 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Conditt, Jessica. "Pokemon Sun And Moon Hit The Nintendo 3DS This Holiday". Engadget. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- Kamen, Matt (12 January 2016). "Pokémon marks 20th birthday with retro 2DS bundles". Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- Farokhmanesh, Megan (12 January 2016). "Pokémon celebrates its 20th anniversary with a New Nintendo 3DS bundle this February". Polygon. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- "Financial Results Briefing for Fiscal Year Ended March 2016". Nintendo. 28 April 2016. p. 3. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "Pokemon Red Version for Game Boy". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "Pokemon Blue Version for Game Boy". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- McCaul, Scott. "Pokemon Blue Version -Review". Allgame. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ポケットモンスター 赤/緑 まとめ [ゲームボーイ]. Famitsu (in Japanese). Enterbrain, Inc.

- "Now Playing: Pokémon". Nintendo Power. 113: 112. October 1998.

- Safier, Joshua; Nakaya, Sumie (7 February 2000). "Pokemania: Secrets Behind the International Phenomenon". Columbia Business School. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- Bodle, Andy and Greg Howson (30 September 1999). "Monsters to the rescue". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- "Pokémon". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Pokemon Franchise Approaches 150 Million Games Sold". Nintendo. PR Newswire. 4 October 2005. Archived from the original on 26 April 2007.

- Ohbuchi, Yutaka (5 February 1998). "Japan's Top Ten of '97". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 1 March 2000.

- "Japan Platinum Game Chart". The Magic Box. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007.

- "US Platinum Videogame Chart". The Magic Box. 27 December 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- "50 Most Popular Video Games of All Time". 247wallst.com. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "All-time best selling console games worldwide 2018 | Statistic". Statista. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- DeVries, Jack (16 January 2009). "IGN: Pokemon Report: World Records Edition". IGN. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- "Nintendo Power – The 20th Anniversary Issue!" (Magazine). Nintendo Power. 231 (231). San Francisco, California: Future US. August 2008: 72. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Reeves, Ben (24 June 2011). "The 25 Best Game Boy Games Of All Time". Game Informer. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- East, Tom (2 March 2009). "Feature: 100 Best Nintendo Games". Official Nintendo Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- Staff (30 April 2003). "The Top 100: 71–80". IGN. Archived from the original on 10 September 2009. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- "IGN's Top 100 Games 061-070". IGN. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- Harris, Craig (29 August 2003). "IGN: Nintendo Celebrates Pokemoniversary". IGN. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- Makuch, Eddie (27 November 2017). "Pokemon Game Sales Pass 300 Million Units". GameSpot. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Twitch plays Pokémon: The largest 'massively multiplayer' Pokémon game is beautiful chaos". The Independent. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Twitch Plays Pokemon conquers Elite Four, beating game after 390 hours". CNET. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "ポケットモンスター ファイアレッド・リーフグリーン". The Pokémon Company. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "ポケットモンスター ファイアレッド・リーフグリーン". Nintendo. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Pokémon™ FireRed Version and Pokémon™ LeafGreen Version". The Pokémon Company International. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Pokémon™ FireRed Version and Pokémon™ LeafGreen Version". The Pokémon Company International. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- Harris, Craig (26 July 2006). "IGN: Player's Choice, Round Two". IGN. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- "Pokemon FireRed (gba: 2004): Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- "Financial Results Briefing for Fiscal Year Ended March 2008" (PDF). Nintendo. 25 April 2008. p. 6. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

External links

- Official website (US)

- Official website for Pokémon Red and Green (in Japanese)

- Official website for Pokémon Blue (in Japanese)