Picasso's African Period

Picasso's African Period, which lasted from 1906 to 1909, was the period when Pablo Picasso painted in a style which was strongly influenced by African sculpture, particularly traditional African masks and art of ancient Egypt, in addition to non-African influences; Iberian sculpture, Iberian schematic art, Paul Cézanne and El Greco. This proto-Cubist period following Picasso's Blue Period and Rose Period has also been called the Negro Period,[1] or Black Period.[2][3]

Context and period

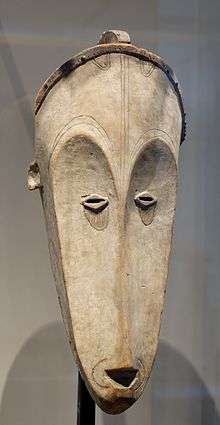

In the early 20th century, African artworks were being brought back to Paris museums in consequence of the expansion of the French empire into Sub-Saharan Africa. The press was abuzz with exaggerated stories of cannibalism and exotic tales about the African kingdom of Dahomey. The mistreatment of Africans in the Belgian Congo was exposed in Joseph Conrad's popular book Heart of Darkness. It was natural in this climate of African interest that Picasso would look towards African artworks as inspiration for some of his work; his interest was sparked by Henri Matisse who showed him a mask from the Dan people of Africa.[4]

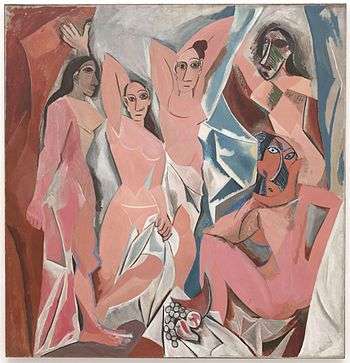

In May or June 1907, Picasso experienced a "revelation" while viewing African art at the ethnographic museum at Palais du Trocadéro.[5] Picasso's discovery of African art influenced the style of his painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (begun in May 1907 and reworked in July of that year), especially in the treatment of the two figures on the right side of the composition.

Picasso continued to develop a style derived from African, Egyptian and Iberian art before beginning the analytic cubism phase of his painting in 1910. Other works of Picasso's African Period include the Bust of a Woman (1907, in the National Gallery, Prague); Mother and Child (Summer 1907, Musée Picasso, Paris); Nude with Raised Arms (1907, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid, Spain); and Three Women (Summer 1908, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg).

Controversy

In historical reflection, a few issues have been pointed out include questioning the origins of this genre of art for Picasso. Primitivism as an aesthetic was often used by Europeans borrowing from non-Western cultures.[6] While it is clear Picasso was inspired heavily by aesthetics from cultures not his own many art historians and critics have argued that this sort of borrowing was a modernist expression.[7]

Art historian Kobena Mercer covers Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon in his book on black diasporic art titled Travel and See. He argues Picasso's stylistic change towards an African inspired aesthetic was individualistic and modern while minority artists receive little to no recognition for their work inspired by their own culture.[8]

It could also be as problematic that in Demoiselles d'Avignon the women painted wearing African-like masks are meant to be prostitutes from Barcelona's red-light district. Picasso masks these white bodies in order to make their sexualization acceptable to a European audience.[9] Picasso himself though said about painting "It's not an aesthetic process; it's a form of magic that interposes itself between us and the hostile universe, a means of seizing power by imposing a form on our terrors as well as on our desires." To him, these masks were a peoples' connection between themselves and the hostile universe he wanted his art to confront. [10]

In February of 2006, an exhibition titled "Picasso and Africa" showcasing Picasso's work from his African period as well as many African sculptures similar to ones he would have been inspired by where shown side by side in Johannesburg, South Africa at the Standard Bank Gallery. A curator involved in the exhibition, Marylin Martin quoted to an article for the Guardian "Picasso never copied African art, which is why this show does not match a specific African work with a Picasso", the goal of the exhibition was not to accuse Picasso of stealing but to show how he transcended it and created a new aesthetic combining his own and his inspiration.[11]

Whether or not Picasso's African period is cultural appropriation or controversial is a fairly new interpretation of his work. Opinions on it differ among art historians and critics. Some like Kobena Mercer argue that he takes away recognition from black diasporic artists while many consider it part of the trajectory of modernism in art and view it as an individualistic approach.

Image gallery

Pablo Picasso, 1907, Nu à la serviette, oil on canvas, 116 x 89 cm

Pablo Picasso, 1907, Nu à la serviette, oil on canvas, 116 x 89 cm Pablo Picasso, 1907, Femme nue, oil on canvas, 92 x 43 cm, Museo delle Culture, Milano

Pablo Picasso, 1907, Femme nue, oil on canvas, 92 x 43 cm, Museo delle Culture, Milano.jpg) Pablo Picasso, 1907, Nu aux bras levés (Nude)

Pablo Picasso, 1907, Nu aux bras levés (Nude)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_61.4_x_47.6_cm%2C_The_Museum_of_Modern_Art%2C_New_York.jpg) Pablo Picasso, 1907, Head of a Sleeping Woman (Study for Nude with Drapery), oil on canvas, 61.4 x 47.6 cm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Pablo Picasso, 1907, Head of a Sleeping Woman (Study for Nude with Drapery), oil on canvas, 61.4 x 47.6 cm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York Pablo Picasso, 1907-08, Vase of Flowers, oil on canvas, 92.1 x 73 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York

Pablo Picasso, 1907-08, Vase of Flowers, oil on canvas, 92.1 x 73 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_66_x_50.5_cm%2C_Hermitage_Museum%2C_Saint_Petersburg%2C_Russia.jpg) Pablo Picasso, 1908, Bols et flacons (Pitcher and Bowls), oil on canvas, 66 x 50.5 cm, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Pablo Picasso, 1908, Bols et flacons (Pitcher and Bowls), oil on canvas, 66 x 50.5 cm, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia Pablo Picasso, 1908, Dryad, oil on canvas, 185 x 108 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Pablo Picasso, 1908, Dryad, oil on canvas, 185 x 108 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_200_x_185_cm%2C_Hermitage_Museum%2C_Saint_Petersburg.jpg) Pablo Picasso, 1908, Trois femmes (Three Women), oil on canvas, 200 x 185 cm, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Pablo Picasso, 1908, Trois femmes (Three Women), oil on canvas, 200 x 185 cm, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg Pablo Picasso, 1908, Seated Woman (Meditation), oil on canvas, 150 x 99 cm, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Pablo Picasso, 1908, Seated Woman (Meditation), oil on canvas, 150 x 99 cm, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_60_x_73_cm%2C_Mus%C3%A9e_Picasso%2C_Paris.jpg) Pablo Picasso, 1908, Paysage aux deux figures (Landscape with Two Figures), oil on canvas, 60 x 73 cm, Musée Picasso, Paris

Pablo Picasso, 1908, Paysage aux deux figures (Landscape with Two Figures), oil on canvas, 60 x 73 cm, Musée Picasso, Paris Pablo Picasso, 1909, Nature morte à la brioche

Pablo Picasso, 1909, Nature morte à la brioche Pablo Picasso, 1909, Brick Factory at Tortosa (L'Usine, Horta de Ebro), oil on canvas, 50.7 x 60.2 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Pablo Picasso, 1909, Brick Factory at Tortosa (L'Usine, Horta de Ebro), oil on canvas, 50.7 x 60.2 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_65_x_81_cm%2C_private_collection.jpg) Pablo Picasso, 1909, Maisons à Horta (Houses on the Hill, Horta de Ebro), oil on canvas, 65 x 81 cm, private collection

Pablo Picasso, 1909, Maisons à Horta (Houses on the Hill, Horta de Ebro), oil on canvas, 65 x 81 cm, private collection.jpg) Pablo Picasso, 1909, Harlequin (L'Arlequin)

Pablo Picasso, 1909, Harlequin (L'Arlequin) Pablo Picasso, 1909, Buste de femme (Femme en vert, Femme assise), oil on canvas, 100.3 x 81.3 cm, Van Abbemuseum, Netherlands. This painting from the collection of Wilhelm Uhde was confiscated by the French state and sold at the Hôtel Drouot in 1921

Pablo Picasso, 1909, Buste de femme (Femme en vert, Femme assise), oil on canvas, 100.3 x 81.3 cm, Van Abbemuseum, Netherlands. This painting from the collection of Wilhelm Uhde was confiscated by the French state and sold at the Hôtel Drouot in 1921%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_60.3_x_51.1_cm%2C_The_Art_Institute_of_Chicago.jpg) Pablo Picasso, 1909, Head of a Woman (Tête de femme), oil on canvas, 60.3 x 51.1 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago

Pablo Picasso, 1909, Head of a Woman (Tête de femme), oil on canvas, 60.3 x 51.1 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago

See also

Notes

- Howells 2003, p. 66.

- Christopher Green, 2009, Cubism, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press

- Douglas Cooper, The Cubist Epoch, London: Phaidon in association with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art & the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970. ISBN 0-87587-041-4

- Matisse may have purchased this piece from Emile Heymenn's shop of non-western artworks in Paris, see PabloPicasso.org.

- Picasso, Rubin, and Fluegel 1980, p. 87.

- "Centre Investigador en Art Primitiu i Primitivisme (UPF)".

- Burgard, Timothy Anglin (1991). "Picasso and Appropriation". The Art Bulletin. 73 (3): 479–494. doi:10.2307/3045817. JSTOR 3045817.

- Mercer, Kobena (2016). Travel and See. Durham and London: Duke University Press. p. 236.

- "Pablo Picasso. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Paris, June-July 1907 | MoMA".

- Meldrum, Andrew (15 March 2006). "Andrew Meldrum: How much did Picasso's paintings borrow from African art?". The Guardian.

- Meldrum, Andrew (15 March 2006). "Andrew Meldrum: How much did Picasso's paintings borrow from African art?". The Guardian.

References

- Barr, Alfred, H, Jr. Picasso: Fifty Years of His Art (1946)

- Richardson John. A Life of Picasso. The Prodigy, 1881-1906. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. ISBN 978-0-307-26666-8

- Richardson, John. A Life of Picasso, The Cubist Rebel 1907-1916. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. ISBN 978-0-307-26665-1

- Picasso, P., Rubin, W. S., & Fluegel, J. Pablo Picasso, a retrospective. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1980. ISBN 0-87070-528-8

- Rubin, W. S. "Primitivism" in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1984. ISBN 0-87070-534-2

- Howells, R. Visual Culture. Wiley-Blackwell, 2003. ISBN 0-7456-2412-X

- Mercer, Kobena. Travel and See: Black Diaspora Art Practices since the 1980s. Duke University Press, 2016.

- Meldrum, Andrew. “Andrew Meldrum: How Much Did Picasso's Paintings Borrow from African Art?” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 15 Mar. 2006, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2006/mar/15/art.

- Picasso, Pablo. “Pablo Picasso. Les Demoiselles D'Avignon. Paris, June-July 1907: MoMA.” The Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/collection/works/79766.

- “Centre Investigador En Art Primitiu i Primitivisme.” Centre Investigador En Art Primitiu i Primitivisme (UPF), www.upf.edu/en/web/ciap/inici.

- Burgard, Timothy Anglin. “Picasso and Appropriation.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 73, no. 3, 1991, pp. 479–494. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3045817. Accessed 6 May 2020.