Philippine space program

The space program of the Philippines is currently decentralized and is maintained by various agencies under the Department of Science and Technology (DOST). In 2019 the Philippine government passed the "Philippine Space Act" (Republic Act 11363) which would see the unification and centralization of space research and development under the newly created Philippine Space Agency (PhilSA). The space program is funded through the National SPACE Development Program (NSDP) by the DOST and will receive an initial budget of ₱1 billion in 2020.

Efforts to establish a Philippine space program started as early as the 1960s, when the government built an Earth satellite receiving station. US President Lyndon Johnson discussed with then-Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos in 1966 about the possibility of establishing a joint US–Philippine space program to monitor storms in Asia. If such plans had pushed through it would have been the first time Asians would have gotten involved in space activities.[1] Development continued in the late 80s with the country's first satellites, Agila-1 which was originally launched as an Indonesian satellite.[2] A decade later, the Mabuhay Satellite Corporation entered into service Agila-2, the first Filipino-owned satellite to be launched to space, which deployed into orbit by Chinese Chang Zheng 3B rocket and was launched from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in the Sichuan province on 20 August 1997.

It would be almost two decades before the Philippines would launch another satellite into space when government scientists from DOST and researchers from the University of the Philippines partnered with the Tohoku and Hokkaido Universities of Japan under the PHL-microsat program to launch Diwata-1, the first microsatellite designed and constructed by Filipinos and was deployed into orbit on from the International Space Station (ISS) on April 27, 2016.[3] The Philippines in cooperation with foreign space agencies such as NASA and JAXA were able to deploy develop and launch two additional small-scale satellites, Diwata-2 and Maya-1, with plans to launch additional satellites by 2022.[4][5]

Organization

Several government agencies under the DOST currently maintains the country's space program are the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA), and the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC)[6][7][8]. The DOST and the Manila Observatory crafted a 10-year masterplan in 2012 to make the Philippines a "space-capable country" by 2022.[9] New programs and future space missions will be directed by the newly created Philippine Space Agency (PhilSA).

Challenges

The Philippine space program has two primary challenges[10]:

① Insufficient funding

② Lack of a centralized agency to manage the space program.

Creation of a unified space agency

The Philippine Space Agency is proposed to be established through legislation particularly through the 17th Congress (25 July 2016 – 4 June 2019)'s "Philippine Space Act of 2016" (House Bill 3637)[11] and "Philippine Space Act" (Senate Bill No. 1211).[12] On 27 November 2018, The House of Representatives passed the alternative bill, the "Philippine Space Development Act" (HB 8541)[13], on the 2nd reading. "The bill also provides for a Philippine Space Development and Utilization Policy (PSDUP) that shall serve as the country’s primary strategic roadmap for space development and embody the country’s central goal of becoming a space-capable and space-faring nation in the next decade." Under HB 8541, at least 30 hectares will be allocated to the new PhilSA for an official site within the Clark Special Economic Zone in Pampanga and Tarlac.[14] DOST Secretary Fortunato dela Peña seems to favor HB 8541[15]

As of December 2018, HB 8541 has been approved on the third and final reading with 207 affirmative votes with no votes against or abstentions. It will be attached to the DOST and the bill also creates the Philippine Space Development Fund to be used exclusively for its operation. The astronomical space-related functions of the Department of Transportation (DOTr) and DOST will also be transferred to the Philippine Space Agency, under the bill.[16]

The "Philippine Space Act" (Senate Bill 1983) was passed with 18 senators approving for the proposed legislation's passage with no negative votes in May 2019,[17] hence dedicating ₱1 billion from the current fiscal year's appropriation with subsequent funding from the General Appropriations Act, plus an additional ₱1bil from the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation (PAGCOR) & Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA) with ₱2 billion released annually.[18] The Bicameral Committee ratified HB 8541 on 4 June 2019 placing the space agency under the DOST. The proposed legislation (a harmonization of HB 8541 & SBN 1983) was due for signing into law by President Rodrigo Duterte.[19] The Senate info-page for Senate Bill 1983 reports presentation of the harmonized bill to the Presidential Malacañang Palace on 9 July 2019.[20] The "Philippine Space Act" (Republic Act 11363) was signed into law by Pres. Duterte on 8 August 2019.[21][22]

The agency is currently focused on developing additional micro and nano-satellites and has not discounted developing rocket launch capability in the long term.[23]

History

.jpg)

Origins

The Manila Observatory was established during the Spanish colonial period in 1865 and was the only formal meteorological and astronomical research and services institution in the Philippines and remained so until the creation of the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) in 1972.[24]

Marcos Era

In the mid-1960s, the Philippine Communications Satellite (Philcomsat) was established when the Marcos government built an Earth satellite receiving station.[25] Philcomsat was a founding member of Intelsat, an international satellite consortium.[26] It also had an exclusive franchise for satellite communication in Southeast Asia, as well as in Korea and Japan. It was also responsible for providing the equipment which enabled people in Asia to watch the Apollo 11 launch, which took place in July 16, 1969.[27] The wholly government-owned company became a private corporation in 1982.[25] Marcos also by the virtue of Presidential Decree No. 286 created the Philippine Aerospace Development Corporation (PADC) a Philippine state owned aerospace and defense technology corporation attached to the Department of National Defense, to establish a "reliable aviation and aerospace industry" in the Philippines, design, manufacture and sell "all forms" of aircraft, as well as to develop indigenous capabilities in the maintenance, repair, and modification of aviation equipment.

On April 23, 1980, the Philippines became one of the initial 11 signatories to the Moon Treaty.[24]

PASI & Mabuhay's satellite ventures

.jpg)

In 1974, the Philippines planned to use satellites to improve communications. The leasing of satellites from Intelsat was considered but it was later decided to lease capacity from the Indonesian Palapa system. There were interests for a national communication satellite but initiatives to obtain one did not start until 1994, when the Philippine Agila Satellite Inc. (PASI), a consortium of 17 companies, was established to operate and purchase domestic satellites.[28][29]

The Mabuhay Satellite Corporation (MSC), another consortium, was formed in the same year by PLDT, which was a former member of PASI. PLDT was the largest member of PASI before its departure from the consortium. MSC was composed of numerous domestic telecommunications and broadcasting companies, along with Indonesia-based Pasifik Satelit Nusantara and China-based Everbright Group.[29] [30]

Then, President Fidel V. Ramos expressed his desire for a Philippine satellite to be in orbit in time for the APEC Summit to be held in the country in November 1996.[29]

Early Communication Satellites

First satellite through acquisition while in orbit

MSC complied with the acquisition of Indonesian satellite Palapa B-2P from Pasifik Satelit Nusantara. The satellite was moved to a new orbital slot on August 1, 1996. The satellite was renamed Agila-1 and became the first satellite in orbit to be owned by the country.[31][32][33]

First Satellite launched into space

MSC launched the country's second satellite, Agila-2, with assistance of China. The communications satellite was launched through the Long March 3B at the Xichang Satellite Launch Center on August 19, 1997. The satellite was acquired by Asia Broadcast Satellite in 2011[34] and was renamed to ABS-3.

PHL-Microsat Program

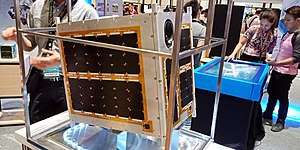

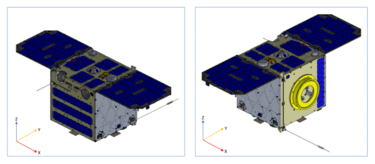

The DOST initiated the Philippine Scientific Earth Observation Microsatellite (PHL-Microsat) program to send two microsatellites in 2016 and 2017. The effort is part of the country's disaster risk management program. A receiving station will also be built in the country.[35][36] The efforts were part of a bigger project, together with seven other Asian countries aside from Japan and the Philippines, to create a network of about 50 microsatellites.[37]

.jpg)

First micro-satellite

The first satellite under this program Diwata-1, the first satellite designed and assembled by Filipinos, with cooperation from Hokkaido University and Tohoku University.[38] One of the major goals of the PHL-Microsat program is to boost the progress on the creation of the Philippine Space Agency.[39] The satellite was deployed from the International Space Station on April 27, 2016. This satellite was succeeded on October 29, 2018, by Diwata-2, which was launched directly into orbit from the Tanegashima Space Center in Japan.[40][41][42]

First nanosatellite

The first nanosatellite, Maya-1 was also deployed from the ISS in the Japanese Kibo module along with two other satellites from Bhutan and Malaysia on August 10, 2018. This achievement was done

Creation of the Philippine Space Agency (PhilSA)

President Rodrigo Duterte in February 2018 announced that a precursor to a space agency, the National Space Development Office, will be established. As of March 2018, there are seven pending bills in both the House of Representatives and the Senate seeking to establish the Philippine Space Agency (PhilSA).[10] In the meantime, the DOST has agreed with the Russian space agency Roscosmos, "to proceed with negotiations of an intergovernmental framework agreement on space cooperation that will include use of Russian rockets to launch Philippine payloads such as micro- and nano-satellites as well as the establishment of a receiving station for the Global Navigation Satellite System" (GLONASS), Russia's alternative to American Global Positioning System (GPS)[43]

In late-January 2019, the Department of Science and Technology has said that the Philippines is already capable to found its own space agency with a pending bill already passed in the House of Representatives and a pending counterpart legislation already pending in the Senate. By this time since 2010, the science department has already spent ₱7.48 billion (or $144 million) for space research and development, aided 5,500 scholars, trained more than 1,000 space science experts, and established 25 facilities in various parts of the Philippines.[23]

List of Philippine satellites

| Designation | Launch | Deployment | Mission Status | Summary | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Site | Vehicle | Date | Site | Vehicle | |||

| Agila-1 | March 20, 1987 | March 20, 1987 | Earth Orbit | N/A | Deorbited on January 1998 | First Philippine satellite through acquisition while in orbit | ||

| Agila-2 | August 19, 1997 | August 19, 1997 | Earth Orbit | N/A | Active: Sold to Asia Broadcast Satellite | First Philippine Satellite launched into space | ||

| Diwata-1 | March 23, 2016 | April 27, 2016 | ISS | Decommissioned on 6 April 2020[44] | First microsatellite of the Philippines | |||

| Maya-1 | June 29, 2018 | August 10, 2018 | ISS | Active | First nanosatellite of the Philippines. | |||

| Diwata-2 | October 29, 2018 | October 29, 2018 | Earth Orbit | N/A | Active | Replacement of Diwata-1 | ||

| Maya-2[45] | TBA | TBA | TBA | TBA | TBA | TBA | Planned | Replacement of Maya-1 |

| Diwata-3[45] | 2022 (planned) | TBA | TBA | 2022 (planned) | TBA | TBA | Planned | Replacement of Diwata-2 |

Space education

The Department of Science and Technology–Science Education Institute (DOST-SEI) launched the first Philippine Space Science Education Program (PESSAP) in 2004, to promote science and technology, particularly space science, as a field of study to the Filipino youth.[46]

On October 5, 2017, high school students from St. Cecilia's College-Cebu, Inc. launched 3-feet solid propellant Model rockets for the World Space Week 2017 celebration in Cebu City.[47]

Student-researchers and science faculty from St. Cecilia's College - Cebu, Inc. in partnership with Department of Science and Technology-Philippine Council for Industry, Energy and Emerging Technology Research and Development (DOST-PCIEERD) successfully launched the first High-Altitude Balloon Life Support System "Karunungan" (HAB LSS Karunungan) in May 2018 at Minglanilla, Cebu, Philippines and floated above the Armstrong Line to simulate 'space like' conditions for future space flights.[48][49]

Gallery

See also

References

- "Philippine chief lauds U.S. stand in Vietnam". St. Petersburg Times. 16 September 1966. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- "Mabuhay acquires Indon satellite;sets new orbit". Manila Standard. July 25, 1996. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- "First Philippine microsatellite "DIWATA" set to launch". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 18 January 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- Resurreccion, Lyn (2018-08-12). "PHL 'won't be left out now' in space program | Lyn Resurreccion". BusinessMirror. Retrieved 2020-06-27.

- Share; Twitter; Twitter; Twitter. "DOST execs note importance of Space Agency creation". www.pna.gov.ph. Retrieved 2020-06-27.

- Luces, Kim (October 15, 2013). "Reaching for the stars: Why the Philippines needs a space program". GMA News. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- Cinco, Maricar (November 7, 2012). "Gov't space agency pushed". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- Pineda, Oscar (March 10, 2013). "Country needs to upgrade weather detection gear". Sun Star Cebu. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- Usman, Edd (29 March 2015). "PH to become 'space-capable' in 10 yrs, according to DOST". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- de Guzman, Chad (23 March 2018). "PH takes small steps, as it aims for giant leaps in space technology". CNN Philippines. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- "Philippine Space Act of 2016" (PDF). 17th Philippine House of Representatives. 15 September 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "SBN-1211: Philippine Space Act". 17th Congress of the Philippines#Senate. 15 September 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "Philippine Space Development Act" (PDF). 17th Philippine House of Representatives. 5 November 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "House okays PH Space Dev't bill on 2nd reading". Philippine News Agency. 27 November 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- Arayata, Ma. Cristina (1 February 2019). "DOST execs note importance of Space Agency creation". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Roxas, Pathricia Ann V. (December 4, 2018). "Philippine space development bill gets House nod". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- Cervantes, Filane Mikee (20 May 2019). "Senate approves creation of PH Space Agency". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "Senate approves creation of PH Space Agency". Philippine News Agency. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Tumampos, Stephanie (4 June 2019). "Philippine Space Agency, ready for President Duterte's signature". BusinessMirror. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "SBN-1983: Philippine Space Act Leg. History". 17th Congress of the Philippines#Senate. 30 June 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Parrocha, Azer (13 August 2019). "Duterte signs law creating Philippine Space Agency". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- Esguerra, Darryl John (13 August 2019). "Duterte signs law creating Philippine Space Agency". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- "Philippines ready and able to create its own space agency, minister says". The Japan Times. Kyodo. 1 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Tumampos, Stephanie; Resurreccion, Lyn (29 October 2018). "PHL flying high–into space". BusinessMirror. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Wealth of Marcos recovered". Gadsden Times. Associated Press. 23 March 1986. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- "Businessman urged gov't to set up satellite". Manila Standard. 12 December 1993. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Space Age plant due in Dutchess". Wappingers Falls: The Evening News. 26 July 1969. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- Martin, Donald (2000). "Asian African South American and Australian Satellites - Philippines". Communication Satellites (illustrated ed.). AIAA. p. 463. ISBN 1884989098.

- MacKie-Mason, Jeffrey; Waterman, David (26 November 2013). "Communication Satellite Policies in Asia". Telephony, the Internet, and the Media: Selected Papers From the 1997 Telecommunications Policy Research Conference. Routledge. pp. 239–242. ISBN 1136684263.

- "PLDT Forms satellite firm". Manila Standard. 2 November 1994. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Mabuhay acquires Indon satellite;sets new orbit". Manila Standard. July 25, 1996.

- "Mabuhay Acquires Pasifik Satellite". Telecompaper. August 6, 1996. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- "Palapa B-2P". Weebau Space Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- "Agila 2 / ABS 5 → ABS 3". space.skyrocket.de. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- De Guzman, RJ (June 24, 2014). "PH soon in space; DOST to launch satellite by 2016". Kicker Daily News. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- Usman, Edd; Wakefield, Francis (June 30, 2014). "PH to launch own microsatellite in 2016". Manila Bulletin.

- "Asian Universities + Asian Nations Go Small... Monitor Natural Disasters w/Network Of Microsatellites". Satnews Daily. 13 January 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Morimoto, Miki (6 March 2015). "Japanese, Filipino researchers to jointly develop satellites to check typhoon damage". Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 10 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- Usman, Edd (15 January 2016). "DOST says PHL joining Asian 50-microsatellite alliance of 9 countries". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- "PH to launch second micro satellite 'Diwata 2' into space on Oct. 29 - UNTV News | UNTV News". www.untvweb.com. Retrieved 2018-10-29.

- "PH-made microsatellite Diwata-2 flies into space". Rappler. Retrieved 2018-10-29.

- Cabalza, Dexter. "PH successfully sends Diwata-2 microsatellite into space". Retrieved 2018-10-29.

- "DOST Finalizes MOU with Russian Space Agency". Department of Foreign Affairs (Philippines). 7 September 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- Apr 7, Mario Alvaro Limos |; 2020. "Goodbye, Diwata: The Philippines' First Satellite Crashes Back to Earth". Esquiremag.ph. Retrieved 2020-06-27.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Resurreccion, Lyn (12 August 2018). "PHL 'won't be left out now' in space program". BusinessMirror. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- Salazar, Tessa (28 February 2015). "Pinoys engage in 'rocket science' that literally holds water". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Plarisan, Almida (11 October 2018). "SCC Ventures Rocket Science". Lasallian Schools Supervision Services Association Inc.(LASSSAI). Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- Usman, Edd (20 May 2018). "Cebu's young science geeks reach for the sky". Business Mirror. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- Lacamiento, Grace Melanie (20 June 2018). "To go beyond limits". The Freeman. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

.jpg)