Pfizer

Pfizer Inc. (/ˈfaɪzər/)[3] is an American multinational pharmaceutical corporation headquartered in New York City. It is one of the world's largest pharmaceutical companies.[4] It is listed on the New York Stock Exchange, and its shares have been a component of the Dow Jones Industrial Average since 2004.[5] Pfizer ranked No. 57 on the 2018 Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by total revenue.[6]

| |

Entrance to Pfizer headquarters | |

| Public | |

| Traded as | |

| ISIN | US7170811035 |

| Industry | Pharmaceutical |

| Founded | 1849 in New York City |

| Founders | Charles Pfizer Charles F. Erhart |

| Headquarters | |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products | See list |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | ~88,300 (2019)[2] |

| Website | Pfizer.com |

On December 19, 2018, Pfizer announced a joint merger of their consumer healthcare division with UK pharma giant GlaxoSmithKline; the British company will maintain a controlling share (listed at 68%).[7]

The company develops and produces medicines and vaccines for a wide range of medical disciplines, including immunology, oncology, cardiology, endocrinology, and neurology. Its products include the blockbuster drug Lipitor (atorvastatin), used to lower LDL blood cholesterol; Lyrica (pregabalin) for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia; Diflucan (fluconazole), an oral antifungal medication; Zithromax (azithromycin), an antibiotic; Viagra (sildenafil) for erectile dysfunction; and Celebrex (also Celebra, celecoxib), an anti-inflammatory drug.

In 2016, Pfizer Inc. was expected to merge with Allergan to create the Ireland-based "Pfizer plc" in a deal that would have been worth $160 billion.[8] The merger was called off in April 2016, however, because of new rules from the United States Treasury against tax inversions, a method of avoiding taxes by merging with a foreign company.[9] The company has made the second-largest pharmaceutical settlement with the United States Department of Justice.

History

In 1849, Pfizer was founded in New York City by German-American Charles Pfizer and his cousin Charles F. Erhart from Ludwigsburg, Germany. They launched the chemicals business, Charles Pfizer and Company, and Bartlett Street[10] in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where they produced an antiparasitic called santonin. This was an immediate success, although it was the production of citric acid that led to Pfizer's growth in the 1880s. Pfizer continued to buy property to expand its lab and factory. Pfizer's original administrative headquarters was at 81 Maiden Lane in Manhattan.[10]

By 1906, sales totaled $3.4 million.

World War I caused a shortage of calcium citrate, which Pfizer imported from Italy for the manufacture of citric acid, and the company began a search for an alternative supply. Pfizer chemists learned of a fungus that ferments sugar to citric acid, and they were able to commercialize production of citric acid from this source in 1919. The company developed expertise in fermentation technology as a result. These skills were applied to the mass production of the antibiotic penicillin during World War II in response to the need to treat injured Allied soldiers; most of the penicillin that went ashore with the troops on D-Day was made by Pfizer.[11]

Penicillin became very inexpensive in the 1940s, and Pfizer searched for new antibiotics with greater profit potential. They discovered Terramycin (oxytetracycline) in 1950, and this changed the company from a manufacturer of fine chemicals to a research-based pharmaceutical company. Pfizer developed a drug discovery program focused on in vitro synthesis in order to augment its research in fermentation technology. The company also established an animal health division in 1959 with an 700-acre (2.8 km2) farm and research facility in Terre Haute, Indiana.

By the 1950s, Pfizer had established offices in Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Cuba, Mexico, Panama, Puerto Rico, and the United Kingdom. In 1960, the company moved its medical research laboratory operations out of New York City to a new facility in Groton, Connecticut. In 1980, they launched Feldene (piroxicam), a prescription anti-inflammatory medication that became Pfizer's first product to reach one billion dollars in total sales.[12] During the 1980s and 1990s, Pfizer Corporation growth was sustained by the discovery and marketing of Zoloft, Lipitor, Norvasc, Zithromax, Aricept, Diflucan, and Viagra.[13][14]

2000–2010

In this decade, Pfizer grew by mergers, including those with Warner–Lambert (2000), Pharmacia (2003), and Wyeth (2009).

In 2003, the company acquired Esperion Therapeutics for $1.3 billion (later selling the unit in 2008), protecting Lipitor from ETC-216.[15] In 2004, Pfizer announced it would acquire Meridica for $125 million.[15] In 2005, the company acquired Vicuron Pharmaceuticals for $1.9 billion, Idun for just less than $300 million and finally Angiosyn for $527 million.[15]

On June 26, 2006, Pfizer announced it would sell its Consumer Healthcare unit (manufacturer of Listerine, Nicorette, Visine, Sudafed and Neosporin) to Johnson & Johnson for $16.6 billion.[16][17]

Development of torcetrapib, a drug that increases production of HDL, or "good cholesterol", which reduces LDL thought to be correlated to heart disease, was cancelled in December 2006. During a Phase III clinical trial involving 15,000 patients, more deaths occurred in the group that took the medicine than expected, and a sixty percent increase in mortality was seen among patients taking the combination of torcetrapib and Lipitor versus Lipitor alone. Lipitor alone was not implicated in the results, but Pfizer lost nearly $1 billion developing the failed drug and the market value of the company plummeted afterwards.[18][19][20] That same year, the company also announced it would acquire PowerMed and Rivax.[21]

In September 2009, Pfizer pleaded guilty to the illegal marketing of the arthritis drug Bextra for uses unapproved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and agreed to a $2.3 billion settlement, the largest health care fraud settlement at that time.[22]

A July 2010 article in BusinessWeek reported that Pfizer was seeing more success in its battle against makers of counterfeit prescription drugs by pursuing civil lawsuits rather than criminal prosecution. Pfizer has hired customs and narcotics experts from all over the globe to track down fakes and assemble evidence that can be used to pursue civil suits for trademark infringement. Since 2007, Pfizer has spent $3.3 million on investigations and legal fees and recovered about $5.1 million, with another $5 million tied up in ongoing cases.[23]

On May 6, 2013, Pfizer told The Associated Press it would begin selling Viagra directly to patients via its website.[24]

Warner–Lambert acquisition

Pfizer acquired Warner–Lambert in 2000 for $111.8 billion,[25] at the time, created the second largest pharmaceutical company in the world.[26] Warner–Lambert was founded as a Philadelphia drug store in 1856 by William R. Warner. Inventing a tablet-coating process gained Warner a place in the Smithsonian Institution. Parke–Davis was founded in Detroit in 1866 by Hervey Parke and George Davis. Warner–Lambert took over Parke–Davis in 1976, and acquired Wilkinson Sword in 1993 and Agouron Pharmaceuticals in 1999.

Pharmacia acquisition

In 2002, Pfizer merged with Pharmacia. The merger was again driven in part by the desire to acquire full rights to a product, this time Celebrex (celecoxib), the COX-2 selective inhibitor previously jointly marketed by Searle (acquired by Pharmacia) and Pfizer. In the ensuing years, Pfizer carried out a massive restructuring that resulted in numerous site closures and the loss of jobs including Terre Haute, Indiana; Holland, Michigan; Groton, Connecticut; Brooklyn, New York; Sandwich, UK; and Puerto Rico.

Pharmacia had been formed by a series of mergers and acquisitions from its predecessors, including Searle, Upjohn and SUGEN.

In April 1888, Searle was founded in Omaha, Nebraska by Gideon Daniel Searle. In 1908, the company was incorporated in Chicago, Illinois. In 1941, the company established headquarters in Skokie, Illinois. It was acquired by the Monsanto Company, headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1985.

The Upjohn Company was a pharmaceutical manufacturing firm founded in 1886 in Kalamazoo, Michigan, by Dr. William E. Upjohn, a graduate of the University of Michigan medical school. The company was originally formed to make friable pills, which were designed to be easily digested. Greenstone was founded in 1993 by Upjohn as a generics division.[27] In 1995, Upjohn merged with Pharmacia, to form Pharmacia & Upjohn. Pharmacia was created in April 2000 through the merger of Pharmacia & Upjohn with the Monsanto Company and its G.D. Searle unit. The merged company was based in Peapack, New Jersey. The agricultural division was spun off from Pharmacia, as Monsanto, in preparation for the close of the acquisition by Pfizer.[28]

SUGEN, a company focused on protein kinase inhibitors, was founded in 1991 in Redwood City, California, and acquired by Pharmacia in 1999. The company pioneered the use of ATP-mimetic small molecules to block signal transduction. After the Pfizer merger, the SUGEN site was shut down in 2003, with the loss of over 300 jobs, and several programs were transferred to Pfizer. These included sunitinib (Sutent), which was approved for human use by the FDA in January 2006, passed $1 billion in annual revenues for Pfizer in 2010.[29] A related compound, SU11654 (Toceranib), was also approved for canine tumors, and the ALK inhibitor Crizotinib also grew out of a SUGEN program.[30]

In 2003, the new Pfizer made Greenstone (originally established as a division of Upjohn) its generic division, and focused on selling authorized generics of Pfizer's products.[27][31]

In 2008, Pfizer announced 275 job cuts at the Kalamazoo manufacturing facility. Kalamazoo was previously the world headquarters for the Upjohn Company.[32]

Wyeth acquisition

On January 26, 2009, after more than a year of talks between the two companies, Pfizer agreed to buy pharmaceuticals rival Wyeth for a combined US$68 billion in cash, shares and loans, including some US$22.5 billion lent by five major Wall Street banks. The deal cemented Pfizer's position as the largest pharmaceutical company in the world, with the merged company generating over US$20 billion in cash each year, and was the largest corporate merger since AT&T and BellSouth's US$70 billion deal in March 2006.[33] The combined company was expected to save US$4 billion annually through streamlining; however, as part of the deal, both companies must repatriate billions of dollars in revenue from foreign sources to the United States, which will result in higher tax costs. The acquisition was completed on October 15, 2009, making Wyeth a wholly owned subsidiary of Pfizer.[34]

The merger was broadly criticized. Harvard Business School's Gary Pisano told The Wall Street Journal, "the record of big mergers and acquisitions in Big Pharma has just not been good. There's just been an enormous amount of shareholder wealth destroyed."[35] Analysts said at the time, "The Warner–Lambert and Pharmacia mergers do not appear to have achieved gains for shareholders, so it is unclear who benefits from the Wyeth–Pfizer merger to many critics."[36]

King Pharmaceuticals acquisition

In October 2010, Pfizer agreed to buy King Pharmaceuticals for $3.6 billion in cash or $14.25 per share: an approximately 40% premium over King's closing share price October 11, 2010.[37]

2011–present

In February 2011, it was announced that Pfizer was to close its UK research and development facility (formerly also a manufacturing plant) in Sandwich, Kent, which at the time employed 2,400 people.[38] However, as of 2014, Pfizer has a reduced presence at the site;[39] it also has a UK research unit in Cambridge.[40]

On September 4, 2012, the FDA approved a Pfizer pill for a rare type of leukemia. The medicine, called Bosulif, treats chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), a blood and bone marrow disease that usually affects older adults.[41]

In July 2014, the company announced it would acquire Innopharma for $225 million, plus up to $135 million in milestone payments, in a deal that expanded Pfizer's range of generic and injectable drugs.[42]

On January 5, 2015, the company announced it would acquire a controlling interest in Redvax for an undisclosed sum. This deal expanded the company's vaccine portfolio targeting human cytomegalovirus.[43] In March 2015, the company announced it would restart its collaboration with Eli Lilly surrounding the phase III trial of Tanezumab. Pfizer is expected to receive an upfront sum of $200 million.[44] In June 2015, the company acquired two meningitis drugs from GlaxoSmithKline—Nimenrix and Mencevax—for around $130 million, expanding the company's meningococcal disease portfolio of drugs.[45]

In May 2016, the company announced it would acquire Anacor Pharmaceuticals for $5.2 billion, expanding the companies portfolio in both inflammation and immunology drugs areas.[46] On their final trading day, Anacor shares traded for $99.20 each, giving Anacor a market capitalisation of $4.5 billion. In August, the company made a $40 million bid for the assets of the now bankrupt BIND Therapeutics through the U.S. Bankruptcy Court.[47] The same month, the company announced it would acquire Bamboo Therapeutics for $645 million, expanding the company's gene therapy offerings.[48] Later, in August, the company announced the acquisition of cancer drug-maker - Medivation - for $14 billion.[49][50] On Medivation's final day of trading, its shares were valued at $81.44 each, giving an effective market capitalisation of $13.52 billion. Two days later, Pfizer announced it would acquire AstraZeneca's small-molecule antibiotics business for $1.575 billion[51] merging it into its Essential Medicines business[52] In the same month the company licensed the anti-CTLA4 monoclonal antibody, ONC-392, from OncoImmune.[53]

In May 2019 the company announced it would acquire Therachon for $810 million, expanding its rare disease portfolio through Theracons recombinant human fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 compound, aimed at treating conditions such as achondroplasia.[54] In June, Pfizer announced it would acquire Array Biopharma for $10.6 billion boosting its oncology pipeline.[55]

In May 2020, Pfizer began testing four different coronavirus vaccine variations to help end the COVID-19 pandemic and plans to expand human trials to thousands of test patients by September 2020. The pharma giant, which is working alongside German drugmaker BioNTech (NASDAQ:BNTX), injected doses of its potential vaccine, BNT162, into the first human participants in the U.S. in early May. If a vaccine proves safe, Pfizer says they "will be able to deliver millions of doses in the October time frame" and expects to produce hundreds of millions of doses in 2021.[56]

Zoetis

Plans to spin out Zoetis, the Agriculture Division of Pfizer and later Pfizer Animal Health, were announced in 2012. Pfizer filed for registration of a Class A stock with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission on August 13, 2012.[57] Zoetis's IPO on February 1, 2013, sold 86.1 million shares for US$2.2 billion.[58] Pfizer retained 414 million Class B shares, giving it an 83% controlling stake in the firm.[59] The offering's lead underwriters were JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley.[58] Most of the money raised through the IPO was used to pay off existing Pfizer debt.[60]

Attempted AstraZeneca acquisition

In April 2014, it was reported that Pfizer had reignited a $100 billion takeover bid for the UK-based AstraZeneca,[61][62] sparking political controversy in the UK,[63] as well as in the US.[64] On May 19, 2014, a "final offer" of £55 a share was rejected by the AstraZeneca board, which said the bid was too low and imposed too many risks. If successful, the takeover—the biggest in British history—would have made Pfizer the world's largest drug company.[65] Hopes for a renewed bid later in the year were dashed when Pfizer signed a major cancer drug deal with Merck KGaA, selling its sharing rights to develop an experimental immunotherapy drug for a fee of $850 million.[66]

Hospira

In February 2015, Pfizer and Hospira agreed that Pfizer would acquire Hospira for $15.2 billion,[67] a deal in which Hospira shareholders would receive $90 in cash for each share they owned.[68][69] News of the deal sent Hospira share prices up from $63.43 to $87.43 on a volume of 60.7 million shares.[70] Including debt, the deal is valued at around $17 billion.[67] Hospira is the largest producer of generic injectable pharmaceuticals in the world.[71] On the final day of trading, Hospira shares traded for $89.96 each, giving a market capitalisation of $15.56 billion.

Attempted Allergan acquisition

On November 23, 2015, Pfizer and Allergan, plc announced their intention to merge for an approximate sum of $160 billion, making it the largest pharmaceutical deal ever, and the third largest corporate merger in history. As part of the deal, the Pfizer CEO, Ian Read, was to remain as CEO and chairman of the new company, to be called "Pfizer plc", with Allergan's CEO, Brent Saunders, becoming president and chief operating officer. As part of the deal, Allergan shareholders would receive 11.3 shares of the company, with Pfizer shareholders receiving one. The terms proposed that the merged company would maintain Allergan's Irish domicile, resulting in the new company being subject to corporation tax at the Irish rate of 12.5%--considerably lower than the 35% rate that Pfizer paid at the time.[72] The deal was to constitute a reverse merger, whereby Allergan acquired Pfizer, with the new company then changing its name to "Pfizer, plc".[73][74][75] The deal was expected to be completed in the second half of 2016, subject to certain conditions: US and EU approval, approval from both sets of shareholders, and the completion of Allergan's divestiture of its generics division to Teva Pharmaceuticals (expected in the first quarter of 2016).[73] On April 6, 2016, Pfizer and Allergan announced they would be calling off the merger after the Obama administration introduced new laws intended to limit corporate tax inversions (the extent to which companies could move their headquarters overseas in order to reduce the amount of taxes they pay).[76]

Pfizer re-organisation

In 2018 Pfizer announced it would reorganise its business into three separate units; a higher-margin innovative medicines division, a lower-margin, off-patent drug division, and a consumer healthcare division, with a view to focussing on higher margin therapies.[77]

Pfizer Consumer Healthcare

In October 2017, reports emerged that Pfizer were undertaking a strategic review of their Consumer Healthcare division, with possible results ranging from a partial or complete spin-off or a direct sale[78] with the divestment expected to raise in the region of $15 billion for one of the largest Over-the-Counter businesses in the world.[79] Reckitt Benckiser expressed interest in bidding for the division earlier in October[80] with Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, Procter & Gamble[81] and GlaxoSmithKline also being linked with bids for the business.[82] On March 22, Reckitt Benckiser pulled out of the deal, a day later GlaxoSmithKline also pulled out.[83]

In December 2018, GlaxoSmithKline announced that it, along with Pfizer, had reached an agreement to merge and combine their consumer healthcare divisions into a single entity. The combined entity would have sales of around £9.8 billon ($12.7 billion), with GSK maintaining a 68% controlling stake in the joint venture. Pfizer would own the remaining 32% shareholding. The deal builds on an earlier 2018 deal where GSK bought out Novartis' stake in the GSK-Novartis consumer healthcare joint business.[84][85]

Pfizer off-patent drug business

In late July 2019, the company announced that it would spin off and merge its off-patent medicine division, Upjohn, with Mylan, forming a brand new pharmaceutical business with sales of around $20 billion.[86] The new combined business will have a portfolio of drugs and brands including the Epi-Pen, Viagra, Lipitor and Celebrex.[87][88]

The deal will be structured as an all-stock, Reverse Morris Trust transaction:

- Upjohn will be spun off to Pfizer shareholders and then combined with Mylan

- Each share of Mylan's stock will be converted into one share of the new company

- Pfizer shareholders would own 57% of the combined new company and Mylan shareholders will own 43%

Acquisition history

- Pfizer (Founded 1849 as Charles Pfizer & Company)

- Warner–Lambert

- William R. Warner (Founded 1856, merged 1955)

- Lambert Pharmacal Company (Merged 1955)

- Parke-Davis (Founded 1860, Acq 1976)

- Wilkinson Sword (Acq 1993, divested 2003)

- Agouron (Acq 1999)

- Pharmacia (Acq 2002)

- Pharmacia & Upjohn (Merged 2000)

- Esperion Therapeutics (Acq 2003, divested 2008)

- Meridica (Acq 2004)

- Vicuron Pharmaceuticals (Acq 2005)

- Idun (Acq 2005)

- Angiosyn (Acq 2005)

- Powermed (Acq 2006)

- Rinat (Acq 2006)

- Coley Pharmaceutical Group (Acq 2007)

- CovX (Acq 2007)

- Encysive Pharmaceuticals Inc (Acq 2008)

- Wyeth (Acq 2009)

- Chef Boyardee

- S.M.A. Corporation

- Ayerst Laboratories (Acq 1943)

- Fort Dodge Serum Company (Acq 1945)

- Bristol-Myers (Animal Health div)

- Parke-Davis (Animal Health div)

- A.H. Robins

- Sherwood Medical (Acq 1982)

- Genetics Institute, Inc. (Acq 1992)

- American Cyanamid (Acq 1994)

- Lederle Laboratories

- Solvay (Acq 1995, Animal Health div)

- King Pharmaceuticals (Acq 2010)

- Monarch Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

- King Pharmaceuticals Research and Development, Inc.

- Meridian Medical Technologies, Inc.

- Parkedale Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

- King Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc.

- Monarch Pharmaceuticals Ireland Limited

- Synbiotics Corporation (Acq 2011)

- Icagen (Acq 2011)

- Ferrosan (Consumer Health div, Acq 2011)

- Excaliard Pharmaceuticals (Acq 2011)

- Alacer Corp (Acq 2012)

- NextWave Pharmaceuticals, Inc (Acq 2012)

- Innopharma (Acq 2014)

- Redvax GmbH (Acq 2014)

- Hospira (Spun off from Abbott Laboratories 2004, Acq 2015)

- Mayne Pharma Ltd (Acq 2007)

- Pliva-Croatia

- Orchid Chemicals & Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (Generics & Injectables div, Acq 2009)

- Javelin Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Acq 2010)

- TheraDoc (Acq 2010)

- Anacor Pharmaceuticals (Acq 2016)

- Bamboo Therapeutics (Acq 2016)

- Medivation (Acq 2016)

- AstraZeneca (Small molecule antibiotic div, Acq 2016)

- Warner–Lambert

Operations

Pfizer is organised into nine principal operating divisions: Primary Care, Specialty Care, Oncology, Emerging Markets, Established Products, Consumer Healthcare, Nutrition, Animal Health, and Capsugel.[89]

Partnerships

In May 2015, Pfizer and a Bar-Ilan University laboratory announced a partnership based on the development of medical DNA nanotechnology.[90]

Research and development

Pfizer's research and development activities are organised into two principal groups: the PharmaTherapeutics Research & Development Group, which focuses on the discovery of small molecules and related modalities; and the BioTherapeutics Research & Development Group, which focuses on large-molecule research, including vaccines.[89] In 2007, Pfizer invested $8.1 billion in research and development, the largest R&D investment in the pharmaceutical industry.[91]

Pfizer has R&D facilities in the following locations:

- Pearl River, New York

- Groton, Connecticut (Largest R&D site)

- Andover, Massachusetts

- La Jolla, California (around 1,000 staff, focused on cancer drugs);[92]

- South San Francisco, California

- Cambridge, Massachusetts

- St. Louis, Missouri

- Sandwich, United Kingdom

- Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- Morrisville, North Carolina

- Chennai, India

In 2007, Pfizer announced plans to close or sell the Loughbeg API facility, located at Loughbeg, Ringaskiddy, Cork, Ireland by mid to end of 2008. In 2007, Pfizer announced plans to completely close the Ann Arbor, Nagoya and Amboise Research facilities by the end of 2008, eliminating 2,160 jobs and idling the $300 million Michigan facility, which in recent years had seen expansion worth millions of dollars.[93]

On June 18, 2007, Pfizer announced it would move the Animal Health Research (VMRD) division based in Sandwich, England, to Kalamazoo, Michigan.[94] On February 1, 2011, Pfizer announced the closure of the Research and Development centre in Sandwich, with the loss of 2,400 jobs.[95] Pfizer subsequently announced it would be maintaining a significant presence at Sandwich, with around 650 staff continuing to be based at the site.[96]

On September 1, 2011, Pfizer announced it had agreed to a 10-year lease of more than 180,000 square feet of research space from MIT in a building to be constructed just north of the MIT campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The space will house Pfizer's Cardiovascular, Metabolic and Endocrine Disease Research Unit and its Neuroscience Research Unit; Pfizer anticipated moving into the space once it was completed in late 2013.[97]

As of 2013, products in Pfizer's development pipeline included dimebon and tanezumab.

In 2018, Pfizer announced that it would end its work on research into treatments for Alzheimer's disease and Parkinsonism (a symptom of Parkinson's disease and other conditions). The company stated that approximately 300 researchers would lose their jobs as a result.[98]

In 2020, Pfizer partnered with BioNTech, a German biotech firm, to study and develop COVID-19 mRNA vaccine candidates. As of May 2020, the companies had begun Phase I clinical trials with four separate vaccine candidates. The companies plan to use Pfizer facilities to manufacture the vaccine if they receive FDA approval.[99][100]

On June 2, 2020, Pfizer announced that it would, through its Breakthrough Growth Initiative program invest in publicly traded drug developers to fund their treatment candidates and provide access to the its scientific expertise.[101]

Products

As of 2017, Pfizer split its business into two primary segments: (1) innovative health, which includes branded drugs and vaccines, and (2) essential health. In 2016, innovative health generated $29.2 billion in revenue and essential health generated $23.6 billion.[102]

Patented pharmaceuticals

Key current and Pfizer products include:

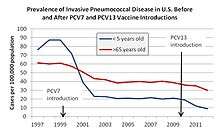

- Prevnar (13-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine) is a vaccine for the prevention of invasive pneumococcal infections. The introduction of the original, 7-valent version of the vaccine in 1999 led to a 75% reduction in the incidence of invasive pneumococcal infections among children under age 5 in the United States. An improved version of the vaccine, providing coverage of 13 bacterial variants, was introduced in early 2010, and granted a patent in India in 2017. As of 2012 the rate of invasive infections among children under age 5 has been reduced by an additional 50%.[103]

- Lyrica (pregabalin) for neuropathic pain. Sales of Lyrica were $4.6 billion in 2013; the US patent on Lyrica was challenged by generic manufacturers and was upheld in 2014, giving Pfizer exclusivity for Lyrica in the US until 2018.[104]

- Xeljanz (tofacitinib) for rheumatoid arthritis and ulcerative colitis, which had sales of $1.77 billion in 2018 and in January 2019 it was top drug in the United States for direct-to-consumer advertising, passing Humira.[105]

Generics

In addition to marketing branded pharmaceuticals, Pfizer is involved in the manufacture and sale of generics. In the US it does this through its Greenstone subsidiary, which it acquired as part of the acquisition of Pharmacia.[106] Pfizer also has a licensing deal in place with Aurobindo, which grants the former access to a variety of oral solid generic products.[107] Key historical generics include:

- Atorvastatin (trade name Lipitor), a statin for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Lipitor was developed by Pfizer legacy company Parke-Davis, a subsidiary of Warner-Lambert and first marketed in 1996.[108] Although atorvastatin was the fifth drug in the class of statins to be developed, clinical trials showed that atorvastatin caused a more dramatic reduction in LDL-C than the other statin drugs. From 1996 to 2012 under the trade name Lipitor, atorvastatin became the world's best-selling drug of all time, with more than $125 billion in sales over approximately 14.5 years.[109] Lipitor alone "provided up to a quarter of Pfizer Inc.'s annual revenue for years."[109] The patent expired in 2011.[110]

- Diflucan (fluconazole), the first orally available treatment for severe fungal infections. Fluconazole is recommended as a first-line treatment in invasive candidiasis[111] and is widely used in the prophylaxis of severe fungal infections in premature infants.[112] Fluconazole is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[113] Patent protection ended in 2004 and 2005.[114]

- Flagyl (metronidazole) is a nitroimidazole antibiotic medication used particularly for anaerobic bacteria and protozoa. It is antibacterial against anaerobic organisms, an amoebicide, and an antiprotozoal.[115] As of 2018, it is second line for first episodes of mild-to-moderate Clostridium difficile infection (formerly was first-line).[116] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[113] The original patent protection ended in 1982, but reformulation evergreening occurred thereafter.[117]

- Norvasc (amlodipine), an antihypertensive drug of the dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker class. Amlodipine is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, a list of the most important medication needed in a basic health system.[113] Patent protection ended in 2007.[118]

- Zithromax (azithromycin), a macrolide antibiotic that is recommended by the Infectious Disease Society of America as a first line treatment for certain cases of community-acquired pneumonia.[119] Patent protection ended in 2005.[120]

- Zoloft (sertraline), is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. It was introduced to the market by Pfizer in 1991. Sertraline is primarily prescribed for major depressive disorder in adult outpatients as well as obsessive–compulsive, panic, and social anxiety disorders in both adults and children. In 2011, it was the second-most prescribed antidepressant on the U.S. retail market, with 37 million prescriptions.[121] The patent expired 2006.[122]

Promotional practices

Pfizer has long been known within the industry as one of the more aggressive marketers of their products.[123][124][125] Access to Wyeth internal documents has revealed marketing strategies used to promote Neurontin for off-label use.[126] In 1993, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved gabapentin (Neurontin, Pfizer) only for treatment of seizures. Warner–Lambert, which merged with Pfizer in 2000, used activities not usually associated with sales promotion, including continuing medical education and research, sponsored articles about the drug for the medical literature, and alleged suppression of unfavorable study results, to promote gabapentin. Within 5 years the drug was being widely used for the off-label treatment of pain and psychiatric conditions. Warner–Lambert admitted to charges that it violated FDA regulations by promoting the drug for pain, psychiatric conditions, migraine, and other unapproved uses, and paid $430 million to resolve criminal and civil health care liability charges.[127][128] A recent Cochrane review concluded that gabapentin is ineffective in migraine prophylaxis.[129] The American Academy of Neurology rates it as having unproven efficacy, while the Canadian Headache Society and the European Federation of Neurological Societies rate its use as being supported by moderate and low-quality evidence, respectively.[130]

In September 2009, Pfizer agreed to pay $2.3 billion to settle civil and criminal allegations that it had illegally marketed four drugs—Bextra, Geodon, Zyvox, and Lyrica—for non-approved uses; it was Pfizer's fourth such settlement in a decade.[131][132][133] The payment included $1.3 billion in criminal penalties for felony violations of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, and $1 billion to settle allegations it had illegally promoted the drugs for uses that were not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and caused false claims to be submitted to Federal and State programs. The criminal fine was the largest ever assessed in the United States up to that time.[134] Pfizer has entered an extensive corporate integrity agreement with the Office of Inspector General and will be required to make substantial structural reforms within the company, and maintain the Pfizer website (pfizer.com/pmc) to track the company's post marketing commitments. Pfizer had to also put a searchable database of all payments to physicians the company had made on the Pfizer website by March 31, 2010.[135]

Peter Rost was vice president in charge of the endocrinology division at Pharmacia before and during its acquisition by Pfizer. During that time he raised concerns internally about kickbacks and off-label marketing of Genotropin, Pharmacia's human growth hormone drug. Pfizer reported the Pharmacia marketing practices to the FDA and Department of Justice; Rost was unaware of this and filed an FCA lawsuit against Pfizer. Pfizer kept him on, but isolated him until the FCA suit was unsealed in 2005. The Justice Department declined to intervene, and Pfizer fired him, and he filed a wrongful termination suit against Pfizer.[136] Pfizer won a summary dismissal of the case, with the court ruling that the evidence showed Pfizer had decided to fire Rost prior to learning of his whistleblower activities.[137]

A "whistleblower suit" was filed in 2005 against Wyeth, which was acquired by Pfizer in 2009, alleging that the company illegally marketed their drug Rapamune. Wyeth is targeted in the suit for off-label marketing, targeting specific doctors and medical facilities to increase sales of Rapamune, trying to get current transplant patients to change from their current transplant drugs to Rapamune and for specifically targeting African-Americans. According to the whistleblowers, Wyeth also provided doctors and hospitals with kickbacks to prescribe the drug in the form of grants, donations and other money.[138][139] In 2013, the company pleaded guilty to criminal mis-branding violations under the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. By August 2014 it had paid $491 million in civil and criminal penalties.[140]

According to Harper's Magazine publisher John MacArthur, Pfizer withdrew "between $400,000 and a million dollars" worth of ads from their magazine following an unflattering article on depression medication.[141]

Controversies

Pfizer is party to a number of lawsuits stemming from its pharmaceutical products as well as the practices of various companies it has merged with or acquired.[131][132][133]

Quigley Co.

Pfizer acquired Quigley in 1968, and the division sold asbestos-containing insulation products until the early 1970s.[142] Asbestos victims and Pfizer have been negotiating a settlement deal that calls for Pfizer to pay $430 million to 80 percent of existing plaintiffs. It will also place an additional $535 million into an asbestos settlement trust that will compensate future plaintiffs as well as the remaining 20 percent of current plaintiffs with claims against Pfizer and Quigley. The compensation deal is worth $965 million all up. Of that $535 million, $405 million is in a 40-year note from Pfizer, while $100 million will come from insurance policies.[143]

Bjork–Shiley heart valve

Pfizer purchased Shiley in 1979 at the onset of its Convexo-Concave valve ordeal, involving the Bjork–Shiley heart valve. Approximately 500 people died when defective valves failed and, in 1994, the United States ruled against Pfizer for ~$200 million.[144][145]

Abdullahi v. Pfizer, Inc and Trovafloxacin (Trovan) Controversy.

In 1996, an outbreak of measles, cholera, and bacterial meningitis occurred in Nigeria. Pfizer representatives and personnel from a contract research organization (CRO) traveled to Kano, Nigeria to set up a clinical trial and administer an experimental antibiotic, trovafloxacin, to approximately 200 children.[146] Local Kano officials report that more than 50 children died in the experiment, while many others developed mental and physical deformities.[147] The nature and frequency of both fatalities and other adverse outcomes were similar to those historically found among pediatric patients treated for meningitis in sub-Saharan Africa.[148] In 2001, families of the children, as well as the governments of Kano and Nigeria, filed lawsuits regarding the treatment.[149] According to the news program Democracy Now!, "[r]esearchers did not obtain signed consent forms, and medical personnel said Pfizer did not tell parents their children were getting the experimental drug."[150] The lawsuits also accuse Pfizer of using the outbreak to perform unapproved human testing, as well as allegedly under-dosing a control group being treated with traditional antibiotics in order to skew the results of the trial in favor of Trovan. While the specific facts of the case remain in dispute, both Nigerian medical personnel and at least one Pfizer physician have stated that the trial was conducted without regulatory approval.[151][152]

In 2007, Pfizer published a Statement of Defense letter.[153] The letter states that the drug's oral form was safer and easier to administer, that Trovan had been used safely in over 5000 Americans prior to the Nigerian trial, that mortality in the patients treated by Pfizer was lower than that observed historically in African meningitis epidemics, and that no unusual side effects, unrelated to meningitis, were observed after 4 weeks.

In June 2010, the US Supreme Court rejected Pfizer's appeal against a ruling allowing lawsuits by the Nigerian families to proceed.[154]

In December 2010, WikiLeaks released US diplomatic cables, which indicate that Pfizer had hired investigators to find evidence of corruption against Nigerian attorney general Aondoakaa to persuade him to drop legal action.[155] Washington Post reporter Joe Stephens, who helped break the story in 2000, called these actions "dangerously close to blackmail."[150] In response, the company has released a press statement describing the allegations as "preposterous" and stating that they acted in good faith.[156] Aondoakka, who had allegedly demanded bribes from Pfizer in return for a settlement of the case,[157] was declared unfit for office and had his U.S. visa revoked in association with corruption charges in 2010.[158][159]

Retrovirus lawsuit

A scientist claims she was infected by a genetically modified virus while working for Pfizer. In her federal lawsuit she says she has been intermittently paralyzed by the Pfizer-designed virus. "McClain, of Deep River, suspects she was inadvertently exposed, through work by a former Pfizer colleague in 2002 or 2003, to an engineered form of the lentivirus, a virus similar to the one that can lead to acquired immune deficiency syndrome, also known as AIDS."[160] The court found that McClain failed to demonstrate that her illness was caused by exposure to the lentivirus,[161] but also that Pfizer violated whistleblower laws.[162]

Blue Cross Blue Shield

Health insurance company Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) filed a lawsuit against Pfizer for reportedly illegally marketing their drugs Bextra, Geodon and Lyrica. BCBS is reporting that Pfizer used "kickbacks" and wrongly persuaded doctors to prescribe the drugs.[163][164] FiercePharma reported that "According to the suit, the drugmaker not only handed out those "misleading" materials on off-label uses, but sent doctors on Caribbean junkets and paid them $2,000 honoraria in return for their listening to lectures about Bextra. More than 5,000 healthcare professionals were entertained at meetings in Bahamas, Virgin Islands, and across the U.S., the suit alleges."[165][166] The case was settled in 2014 for $325M.[167]

Brigham Young University

Controversy arose over the drug "Celebrex". Brigham Young University (BYU) said that a professor of chemistry, Dr. Daniel L. Simmons, discovered an enzyme in the 1990s that would later lead towards the development of Celebrex. BYU was originally seeking 15% royalty on sales, which would equate to $9.7 billion. The court filings show that a research agreement was made with Monsanto, whose pharmaceutical business was later acquired by Pfizer, to develop a better aspirin. The enzyme that Dr. Simmons claims to have discovered would induce pain and inflammation while causing gastrointestinal problems, which Celebrex is used to reduce those issues. A battle ensued, lasting over six years, because BYU claimed that Pfizer did not give him credit or compensation while Pfizer claims it had met all obligations regarding the Monsanto agreement. This culminated in a $450 million amicable settlement without going to trial. Pfizer said it would take a $450 million charge against first quarter earnings to settle.[168]

Litigation in which Pfizer was not a party

Pfizer was discussed as part of the Kelo v. New London case that was decided by U.S. Supreme Court in 2005. In February 1998 Pfizer announced it would build a research facility in New London, Connecticut, and local planners, hoping to promote economic development and build on the influx of jobs the planned facility would bring to the town, created a plan that included seizing property to redevelop it under eminent domain, and local residents sued to stop the seizure. The case went to the Supreme Court, and with regard to Pfizer, the court cited a prior decision that said: "The record clearly demonstrates that the development plan was not intended to serve the interests of Pfizer, Inc., or any other private entity, but rather, to revitalize the local economy by creating temporary and permanent jobs, generating a significant increase in tax revenue, encouraging spin-off economic activities and maximizing public access to the waterfront”.[169] The Supreme Court allowed the eminent domain to proceed.[169] Pfizer opened the facility in 2001 but abandoned it in 2009, angering residents of the town.[170]

Environmental record

Between 2002 and 2008, Pfizer reduced its greenhouse emissions by 20%,[171] and committed to reducing emissions by an additional 20% by 2012. In 2012 the company was named to the Carbon Disclosure Project's Carbon Leadership Index in recognition of its efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.[172]

Pfizer has inherited Wyeth's liabilities in the American Cyanamid site in Bridgewater, New Jersey. This site is highly toxic and an EPA declared Superfund site. Pfizer has since attempted to remediate this land in order to clean and develop it for future profits and potential public uses.[173] The Sierra Club and the Edison Wetlands Association have come out in opposition to the cleanup plan, arguing that the area is subject to flooding, which could cause pollutants to leach. The EPA considers the plan the most reasonable from considerations of safety and cost-effectiveness, arguing that an alternative plan involving trucking contaminated soil off site could expose cleanup workers. The EPA's position is backed by the environmental watchdog group CRISIS.[174]

In June 2002, a chemical explosion at the Groton plant injured seven people and caused the evacuation of over 100 homes in the surrounding area.[175]

Political lobbying

Pfizer is a leading member of the U.S. Global Leadership Coalition, a Washington D.C.-based coalition of over 400 major companies and NGOs that advocates for a larger International Affairs Budget, which funds American diplomatic, humanitarian, and development efforts abroad.[176]

Pfizer is one of the single largest lobbying interests in United States politics. For example, in the first 9 months of 2009 Pfizer spent over $16.3 million on lobbying US congressional lawmakers, making them the sixth largest lobbying interest in the US (following Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), which ranked fourth but also represents many of their interests). A spokeswoman for Pfizer said the company “wanted to make sure our voice is heard in this conversation” in regards to the company's expenditure of $25 million in 2010 to lobby health care reform.[177]

According to U.S. State Department cables released by the whistleblower site WikiLeaks, Pfizer "lobbied against New Zealand getting a free trade agreement with the United States because it objected to New Zealand's restrictive drug buying rules and tried to get rid of New Zealand's former health minister, Helen Clark, in 1990.[178]

In an example of the revolving door between government and industry in the United States, Scott Gotlieb, who resigned as the US FDA Commissioner in April 2019, joined the Pfizer board of directors three months later, in July.[179]

Employment and diversity

Since 2004, Pfizer has received a 100% rating every year on the Corporate Equality Index, released by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation.

In 2012, Pfizer's Canadian division, which then employed 2,890 people, was named one of Montreal's Top 15 Employers, the only research-based pharmaceutical company to receive this honor.[180]

Management

In 2010, Ian Read took over as CEO from Jeff Kindler. In 2019, Ian Read left the CEO role and became executive chairman, with COO Albert Bouria taking the CEO role.[181]

Involvement in developing world health issues

Pfizer makes the anti-fungal drug fluconazole available free of charge to governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in developing countries with a greater than 1% prevalence of HIV/AIDS.[182][183][184] The company has also pledged to provide up to 740 million doses of its anti-pneumococcal vaccine at discounted rates to infants and young children in 41 developing countries in association with the GAVI Alliance.[185]

In 2012, Pfizer and the Gates Foundation announced a joint effort to provide affordable access to Pfizer's long-lasting injectable contraceptive, medroxyprogesterone acetate, to three million women in developing countries.[186]

See also

- Biotech and pharmaceutical companies in the New York metropolitan area

- Companies of the United States with untaxed profits

- Fire in the Blood (2013 film)

- List of pharmaceutical companies

References

- "Financial Review - Pfizer Inc. and Subsidiary Companies" (PDF). Pfizer. 2019. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Pfizer Annual Report 2019" (PDF). Pfizer. 2019.

- Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- "Pfizer moves higher amid persistent breakup talk". Bloomberg Businessweek. March 27, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- "Dow Jones Industrial Average Historical Components" (PDF), moneycontrol.com, archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2011, retrieved November 24, 2015

- "Fortune 500 Companies 2018: Who Made the List". Fortune. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- "GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer merge healthcare arms". BBC. December 19, 2018. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- "Pfizer to buy Allergan in $160 billion deal". Reuters. November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- Humer, Caroline; Banerjee, Ankur (April 6, 2016). "Pfizer, Allergan scrap $160 billion deal after U.S. tax rule change". Reuters.

- Kenneth T. Jackson. The Encyclopedia of New York City. The New York Historical Society; Yale University Press; September 1995. P. 895. ISBN 978-0-300-05536-8

- "A Plan For Big Pharma Involvement In Superbug R&D". July 16, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- "Pfizer Inc: Exploring Our History 1951–1999". Pfizer.

- "Pfizer to pay $20M federal fine; posts 2Q results - Jul. 19, 1999". money.cnn.com. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- Oldani, Michael (2016), "Pfizer", The SAGE Encyclopedia of Pharmacology and Society, SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 1063–1066, doi:10.4135/9781483349985.n303, ISBN 9781483350004, retrieved January 21, 2019

- Munos, Bernard. "Pfizer Does Not Need A Merger, It Needs A Rebellion". Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- "Johnson & Johnson Completes Acquisition Of Pfizer Consumer Healthcare" (Press release). Johnson & Johnson. December 20, 2006. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- Saul, Stephanie (June 27, 2006). "Johnson & Johnson Buys Pfizer Unit for $16.6 billion". The New York Times. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- Berenson, Alex; Pollack, Andrew (December 5, 2006), "Pfizer Shares Plummet on Loss of a Promising Heart Drug", The New York Times, retrieved November 24, 2015

- Berenson, Alex (December 3, 2006). "Pfizer Ends Studies on Drug for Heart Disease". The New York Times. Retrieved December 3, 2006.

- Theresa Agovino (December 3, 2006). "Pfizer ends cholesterol drug development". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 14, 2006. Retrieved December 3, 2006.Each study arm (torcetrapib + Lipitor vs. Lipitor alone) had 7500 patients enrolled; 51 deaths were observed in the Lipitor alone arm, while 82 deaths occurred in the torcetrapib + Lipitor arm.

- Barriaux, Marianne (October 9, 2006). "Pfizer buys vaccine developer PowderMed". the Guardian. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- "Pfizer pays $2.3 billion to settle marketing case", The New York Times, September 2, 2009.

- Bennett, Simeon (July 8, 2010). "Pfizer: Civil Suits for Drug Counterfeiters". BusinessWeek. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "Pfizer to sell Viagra online, in first for Big Pharma: AP". CBS News. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- Pfizer, 2000: Pfizer joins forces with Warner–Lambert, accessed April 7, 2010

- "Here are the 7 biggest mergers of all time". Business Insider. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- Staff (August 1, 2008). "Greenstone LLC - A Successful Business Model". Pharmacy Times.

- "Pharmacia to spin-off Monsanto stake, less than 2 years after firms' merger". Wall Street Journal. mindfully.org. November 28, 2001. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013.

- "Pfizer 2010 annual financial review, p 25" (PDF). Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "Pfizer Drug Targets Gene Flaw to Shrink Lung Tumors (Update1)". Businessweek. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- Hensley, Scott (June 29, 2006). "Pfizer to Make Generic Version of Its Zoloft". Wall Street Journal.

- "Pfizer plant in Michigan to cut 275 – FiercePharma". Archived from the original on October 24, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- Pfizer Agrees to Pay $68 billion for Rival Drug Maker Wyeth By ANDREW ROSS SORKIN and DUFF WILSON. January 26, 2009. The New York Times

- "Wyeth Transaction". Pfizer. Archived from the original on October 19, 2009. Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- The Pfizer–Wyeth Deal Worst-Case Scenario By Jim Edwards | January 23, 2009 – BNET

- Matthew Karnitschnig, & Jonathan D. Rockoff. (2009, January 23). Pfizer in Talks to Buy Wyeth. Wall Street Journal (Eastern Edition), p. A.1. Retrieved March 7, 2010, from Wall Street Journal. (Document ID: 1631280041).

- "Pfizer to buy King Pharma for $3.6 billion in cash". Reuters. October 12, 2010. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- "Pfizer to close UK research site". BBC News. February 1, 2011.

- "Sandwich UK - Pfizer: One of the world's premier biopharmaceutical companies". pfizer.com.

- "Cambridge, UK". pfizer.com.

- "FDA approves Pfizer leukemia drug". Reuters. September 4, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- "GEN - News Highlights:Pfizer to Acquire InnoPharma for Up to $360M". GEN. July 16, 2014.

- "GEN - News Highlights:Pfizer Buys Redvax, Boosting Vaccine Portfolio". GEN. January 5, 2015.

- "GEN - News Highlights:Pfizer, Lilly to Resume Phase III Tanezumab Clinical Program". GEN. March 23, 2015.

- "Pfizer Buys Two GSK Meningitis Vaccines for $130M". GEN. June 22, 2015.

- "Pfizer to Acquire Anacor Pharmaceuticals for $5.2B". GEN. May 16, 2016.

- "Pfizer Places High Bid of $40M for BIND Therapeutics - GEN News Highlights - GEN". July 27, 2016.

- "Pfizer Acquires Bamboo Therapeutics in a $645M Deal - GEN News Highlights - GEN". August 2016.

- "Pfizer to Acquire Medivation for $14B - GEN News Highlights - GEN". August 22, 2016.

- "Pfizer to buy cancer drug firm Medivation for $14bn". BBC News.

- "Pfizer Buys AstraZeneca Antibiotics for Up to $1.575B - GEN News Highlights - GEN". August 24, 2016.

- "Pfizer grabs AZ antibiotics in $1.5B deal. Pre-split prep or just another sales-boosting buy? - FiercePharma".

- "OncoImmune Licenses ONC-392 to Pfizer for Up to $250M". News: Discovery & Development. Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. October 15, 2016. p. 15. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- "Pfizer Acquires Rare-Drug Company Therachon for $810 Million". BioSpace.

- "Pfizer makes $10.6 billion cancer bet in cash deal for Array Biopharma". Reuters. June 17, 2019 – via uk.reuters.com.

- Minkoff, SA Editor Yoel (May 13, 2020). "Pfizer sees expanded coronavirus vaccine trials (NYSE:PFE)". Seeking Alpha. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Zoetis™ Files IPO Registration Statement". Bloomberg L.P. New York. August 13, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- J. de la Merced, Michael (February 1, 2013). "Shares of Zoetis Surge on Debut". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- DIETERICH, CHRIS (January 31, 2013). "Zoetis Raises $2.2 Billion in IPO - WSJ.com". The Wall Street Journal. New York. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- "Shares of animal health company Zoetis soar in IPO". CBS News. New York. February 1, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- Ben Hirschler (April 28, 2014). "Pfizer chases AstraZeneca for potential $100 billion deal". Reuters.

- Brozak, Steve. "No Longer King Of The North, Pfizer Looks To Recapture Crown". Forbes. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- Cameron and Miliband clash over Pfizer deal, BBC News, May 7, 2014.

- US politicians raise questions over Pfizer bid, BBC News, May 9, 2014.

- "AstraZeneca rejects Pfizer 'final' takeover offer, triggers major drop in shares". London Mercury. Archived from the original on May 20, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- Pfizer dampens Astra bid hopes with German Merck cancer deal. Reuters, 17 November 2014

- David Gelles & Katie Thomas. "Pfizer Bets $15 Billion on New Class of Generic Drugs". The New York Times.

- "8-K". sec.gov.

- "Pfizer to Acquire Hospira - Pfizer: One of the world's premier biopharmaceutical companies". pfizer.com.

- Neilan, Catherine (February 5, 2015). "Pfizer, Hospira share prices to soar after $17bn deal announced". Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- "US-based Hospira to buy Orchid Chemicals' injectables biz for $400 mn". The Economic Times.

- "Pfizer seals $160bn Allergan deal to create drugs giant". BBC News. November 23, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- "Pfizer to Acquire Allergan for $160B". GEN. November 23, 2015.

- Cynthia Koons (November 22, 2015). "Pfizer and Allergan to Combine With Joint Value of $160 Billion". Bloomberg.com.

- "Disclaimer - PremierBiopharmaLeader". premierbiopharmaleader.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2015.

- Bray, Chad (April 6, 2016). "Pfizer and Allergan Call Off Merger After Tax-Rule Changes". New York Times. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- "Pfizer To Organize For Future Growth" (Press release). Pfizer. July 11, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Pfizer Reviewing Strategic Alternatives for Consumer Healthcare Business - Pfizer: One of the world's premier biopharmaceutical companies". pfizer.com.

- "Exclusive: Pfizer to launch consumer health sale in November - sources". Reuters. October 26, 2017 – via reuters.com.

- "Reckitt Benckiser's still keen on a Pfizer OTC buy. But can it afford one?". FiercePharma.

- "GlaxoSmithKline eyes Pfizer's OTC unit. But will a buy imperil its dividend?". FiercePharma.

- "Sanofi, J&J could join GlaxoSmithKline, Reckitt in $20B bidding war for Pfizer OTC: report". FiercePharma.

- "GSK pulls out of $20 billion race for Pfizer consumer assets". Reuters. March 23, 2018 – via uk.reuters.com.

- "GlaxoSmithKline plc and Pfizer Inc to form new world-leading Consumer Healthcare Joint Venture - GSK". gsk.com.

- "Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline Announce Joint Venture to Create a Premier Global Consumer Healthcare Company - Pfizer: One of the world's premier biopharmaceutical companies". pfizer.com.

- "Pfizer in talks to merge off-patent drugs business with Mylan: source". Reuters. July 27, 2019 – via uk.reuters.com.

- "Mylan's Merger with Pfizer's Off-Patent Drug Unit Will Create 'New Champion for Global Health'". BioSpace.

- "Pfizer to spinoff, merge off-patent drugs unit with Mylan". Reuters. July 29, 2019 – via uk.reuters.com.

- "Pfizer Leadership and Structure". Pfizer. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- Gali, Weinreb (May 14, 2015). "Pfizer to collaborate on Bar-Ilan DNA robots". Globes. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- "Annual Review 2007 | Pfizer: the world's largest research-based pharmaceutical company". Pfizer. October 9, 2009. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- Pollack, Andrew (September 2, 2009). "For Profit, Industry Seeks Cancer Drugs". The New York Times. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- Pfizer's cuts blindside Ann Arbor workers Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Kalamazoo Gazette, Sunday, January 23, 2007.

- Pfizer Reorganization Could Bring Jobs To Kalamazoo, WWMT.com, June 18, 2007 Archived 21 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Drug giant Pfizer to pull out of Kent". Kentonline.co.uk. February 1, 2011. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "Pfizer site in Sandwich set to retain 650 jobs". BBC News. November 4, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- "Pfizer Expands its Research Footprint in Cambridge". MITnews. September 1, 2011.

- Hiltzik, Michael (January 8, 2018), "Pfizer, pocketing a big tax cut from Trump, will end investment in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's research", Los Angeles Times, retrieved January 27, 2018

- "Pfizer and BioNTech Begin Giving U.S. Test Participants a Potential Covid-19 Vaccine". Barrons. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Pfizer, BioNTech set to begin U.S. coronavirus vaccine trial". Reuters. May 7, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Pfizer to invest up to $500 million in public drug developers". Reuters. June 2, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- Speights, Keith (April 17, 2017). "How Pfizer Inc. Makes Most of Its Money -". The Motley Fool. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- "CDC - ABCs: Surveillance Reports main page - Active Bacterial Core surveillance". April 5, 2019.

- Susan Decker for Bloomberg News. Feb 6, 2014. Pfizer Wins Ruling to Block Generic Lyrica Until 2018

- "Pfizer switches RA patients to lower dose of fast-growing Xeljanz as safety issues arise in postmarketing study". FiercePharma. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- Hollis, Liz "Greenstone – Top 10 Generic Drug Companies 2010" Fierce Pharma, August 10, 2010

- Original Compilation (February 28, 2019). "PFE / Pfizer, Inc. SUBSIDIARIES OF THE COMPANY - Fintel.io". fintel.io. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "List of US FDA Approved Drugs". Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "Lipitor becomes world's top-selling drug". Crain's New York Business via Associated Press. December 28, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- CNN Wire Staff (November 30, 2011). "Lipitor loses patent, goes generic". CNN. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- Charlier C, Hart E, Lefort A, et al. (March 2006). "Fluconazole for the management of invasive candidiasis: where do we stand after 15 years?". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57 (3): 384–410. doi:10.1093/jac/dki473. PMID 16449304.

- Blyth CC, Barzi F, Hale K, Isaacs D (September 2012). "Chemoprophylaxis of neonatal fungal infections in very low birthweight infants: efficacy and safety of fluconazole and nystatin". J Paediatr Child Health. 48 (9): 846–51. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2012.02543.x. PMID 22970680.

- "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- "Pfizer to Expand Fluconazole Donation Program to More than 50 Developing Nations". Kaiser Health News. June 7, 2001. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- "Metronidazole Monograph for Professionals". drugs.com. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- Cohen, S. H.; Gerding, D. N.; Johnson, S.; Kelly, C. P.; Loo, V. G.; McDonald, L. C.; Pepin, J.; Wilcox, M. H.; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America (2010). "Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults: 2010 Update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 31 (5): 431–455. doi:10.1086/651706. PMID 20307191.

- Dickson, Sean (February 25, 2019). "Effect of Evergreened Reformulations on Medicaid Expenditures and Patient Access from 2008 to 2016". Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy. 25 (7): 780–792. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2019.18366. ISSN 2376-0540. PMID 30799664.

- Kennedy VB (22 March 2007). "Pfizer loses court ruling on Norvasc patent". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 3 August 2008.

- Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. (March 2007). "Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults" (PDF). Clin. Infect. Dis. 44 Suppl 2: S27–72. doi:10.1086/511159. PMC 7107997. PMID 17278083.

- "Azithromycin: A world best-selling Antibiotic". wipo.int. World Intellectual Property Organization. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- John M. Grohol (2012). "Top 25 Psychiatric Medication Prescriptions for 2011". Psych Central. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- Smith A (July 17, 2006). "Pfizer needs more drugs". CNNMoney.com. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- Kirkpatrick, By David D. "Inside the Happiness Business". NYMag.com. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- Oldani, Michael (2002). "Tales from the Script" (PDF). Kroeber Society Papers. 87: 147–176 – via University of California Berkeley.

- Oldani, Michael J. (2004). "Thick Prescriptions: Toward an Interpretation of Pharmaceutical Sales Practices". Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 18 (3): 325–356. doi:10.1525/maq.2004.18.3.325. ISSN 1548-1387. PMID 15484967.

- Steinman MA, Bero LA, Chren MM, Landefeld CS (August 2006). "Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents". Ann. Intern. Med. 145 (4): 284–93. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00008. PMID 16908919.

- The settlement was the first off-label promotion case successfully brought under the False Claims Act. Henney JE (August 2006). "Safeguarding patient welfare: who's in charge?". Ann. Intern. Med. 145 (4): 305–7. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00013. PMID 16908923.

- "Warner–Lambert to pay $430 million to resolve criminal & civil health care liability relating to off-label promotion" (Press release). US Department of Justice. May 13, 2004. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- Mulleners WM, McCrory DC, Linde M (August 2014). "Antiepileptics in migraine prophylaxis: An updated Cochrane review". Cephalalgia. 35 (1): 51–62. doi:10.1177/0333102414534325. PMID 25115844.

- Loder E, Burch R, Rizzoli P (June 2012). "The 2012 AHS/AAN guidelines for prevention of episodic migraine: a summary and comparison with other recent clinical practice guidelines". Headache. 52 (6): 930–45. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02185.x. PMID 22671714.

- Harris, Gardiner (September 3, 2009). "Pfizer Pays $2.3 billion to Settle Marketing Case". The New York Times.

- Johnson, Carrie (September 3, 2009). "In Settlement, A Warning To Drugmakers: Pfizer to Pay Record Penalty In Improper-Marketing Case". The Washington Post.

- "Pfizer agrees record fraud fine". BBC. September 2, 2009. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- "The United States Department of Justice – United States Attorney's Office – District of Massachusetts". Archived from the original on March 1, 2010.

- "Corporate Integrity Agreement between the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services and Pfizer Inc" (PDF). Office of Inspector General. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2015.

- Jim Edwards for BrandWeek. March 20, 2006. Bad Medicine. BrandWeek. Original link broken, Created link from internet archive on August 9, 2014. Archive date March 28, 2006.

- "Casetext".

- "Wyeth Marketing Targeted Blacks Illegally: Lawsuit // Pharmalot". Pharmalot.com. May 24, 2010. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- Tracy Staton (June 14, 2010). "Congress joins probe into Wyeth's Rapamune marketing". FiercePharma. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "Pfizer settles more off-label marketing cases tied to Rapamune - FiercePharma".

- Petrovich, Dushko (March 15, 2013). "The Art of Making Magazines edited by Victor S. Navasky and Evan Cornog". Bookforum. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- The Quigley Company, Inc. Trust Quigley Company reorganization

- Crown, Reign (2012). Master. Booktango. ISBN 978-1-4689-2014-7.

over $965 million in settlements

- Blackstone, E.H. (2005). "Could It Happen Again?: The Bjork–Shiley Convexo-Concave Heart Valve Story". Circulation. 111 (21): 2717–2719. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.105.540518. PMID 15927988. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- Bloomfield, P.; et al. (1991). "Twelve-year comparison of a Bjork–Shiley mechanical heart valve with porcine bioprostheses". N Engl J Med. 324 (9): 573–579. doi:10.1056/nejm199102283240901. PMID 1992318.

- Oldani, Michael (2016), "Trovafloxacin (Trovan) Controversy", The SAGE Encyclopedia of Pharmacology and Society, SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 1444–1447, doi:10.4135/9781483349985.n409, ISBN 9781483350004, retrieved January 21, 2019

- Murray, Senan (June 20, 2007). "Africa | Anger at deadly Nigerian drug trials". BBC News. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- Ramakrishnan M, Ulland AJ, Steinhardt LC, Moïsi JC, Were F, Levine OS (2009). "Sequelae due to bacterial meningitis among African children: a systematic literature review". BMC Med. 7: 47. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-7-47. PMC 2759956. PMID 19751516.

- "Nigerians sue Pfizer over test deaths". BBC News. August 30, 2001. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- WikiLeaks Cables: Pfizer Targeted Nigerian Attorney General to Undermine Suit over Fatal Drug Tests, Democracy Now!

- Panel Faults Pfizer in '96 Clinical Trial In Nigeria. The Washington Post. May 7, 2006

- "Pfizer Bribed Nigerian Officials in Fatal Drug Trial, Ex-Employee Claims - CBS News".

- "Trovan, Kano State Civil Case – Statement Of Defense" (PDF). Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "Pfizer-Nigeria appeal dismissed". BBC News. June 29, 2010.

- Boseley, Sarah (December 9, 2010). "WikiLeaks cables: Pfizer 'used dirty tricks to avoid clinical trial payout'". The Guardian. London.

- "Press Statement Regarding Article in The Guardian" (PDF). Pfizer. December 9, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- "In Defense of Blackmail: Why Shouldn't Pfizer Dig Dirt on Crooked Pols? - CBS News".

- "Michael Aondoakaa "Unfit" To Remain SAN, Says CDHR In High-Powered Petition | Sahara Reporters".

- "USAfrica: The Authoritative Link for Africans and Americans".

- "Ex-Pfizer Worker Cites Genetically Engineered Virus In Lawsuit Over Firing". Courant.com. March 14, 2010. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "McClain v. PFIZER, INC., 692 F. Supp. 2d 229". Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- "A Pfizer Whistle-Blower Is Awarded $1.4 Million". The New York Times. April 2, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- "Blue Cross Names and Shames Pfizer Execs Linked to Massages-for-Prescriptions Push | BNET". Industry.bnet.com. June 10, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- Bounds, Jeff (June 10, 2010). "Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas sues Pfizer".

- Tracy Staton (June 11, 2010). "BCBS names Pfizer managers in kickback suit". FiercePharma. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas sues Pfizer over drug marketing | News for Dallas, Texas | Dallas Morning News | Dallas Business News". Dallasnews.com. June 11, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "Pfizer Agrees to $325 Million Neurontin Marketing Accord - Bloomberg".

- Pfizer Settles Lawsuite Archived 1 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Kelo V. New London (04-108) 545 U.S. 469 (2005) 268 Conn. 1, 843 A. 2d 500, affirmed". Cornell University Law School. Retrieved November 27, 2015.

- Mcgeehan, Patrick (November 12, 2009). "Pfizer and 1,400 Jobs to Leave New London, Connecticut". The New York Times.

- "Pfizer Commended For Leadership In Addressing Climate Change For Third Consecutive Year - FierceBiotech".

- "Pfizer Recognized by Carbon Disclosure Project for Carbon Performance | Pfizer: One of the world's premiere biopharmaceutical companies".

- "American Cyanamid Superfund Site" (PDF). The State of New Jersey. December 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2015.

- "Activists say EPA $204M fix for polluted American Cyanamid property will not permanently resolve problem | NJ.com".

- The tempest. The Washington Post. May 28, 2006

- "U.S. Global Leadership Coalition, Global Trust members". Usglc.org. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- Steinbrook, R., 2009. Lobbying, Campaign Contributions, and Health Care Reform Archived June 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine New England Journal of Medicine. 361(23), e52–e52.

- David Fisher & Jonathan Milne (December 19, 2010). "WikiLeaks: Drug firms tried to ditch Clark". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- Mishra, Manas (July 2, 2019). Kuber, Shailesh (ed.). "Senator Warren asks former FDA chief Gottlieb to resign from Pfizer board". Reuters. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- "Montreal's Top Employers 2012" (PDF). Canada's Top 100. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 17, 2012.

- "ON PARTNERS ANNOUNCES TOP EXECUTIVE MOVES OF 2018". ON Partners. January 21, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "AIDS Fungus Drug Offered to Poor Nations". June 7, 2001. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- Sithole, Emelia (February 21, 2001). "S.Africa okays Pfizer AIDS drug distribution". Reuters NewMedia. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2006.

- "Pfizer - Diflucan Commitments". Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- "Pfizer - GAVI commitments". Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- "Pfizer Gates Foundation Press Release". Retrieved August 9, 2014.