Pentatonic scale

A pentatonic scale is a musical scale with five notes per octave, in contrast to the heptatonic scale, which has seven notes per octave (such as the major scale and minor scale).

Pentatonic scales were developed independently by many ancient civilizations.[3] They are still used all over the world, for example traditional music, country music, blues and metal.

There are two types of pentatonic scales: those with semitones (hemitonic) and those without (anhemitonic).

Types

Hemitonic and anhemitonic

Musicology commonly classifies pentatonic scales as either hemitonic or anhemitonic. Hemitonic scales contain one or more semitones and anhemitonic scales do not contain semitones. (For example, in Japanese music the anhemitonic yo scale is contrasted with the hemitonic in scale.) Hemitonic pentatonic scales are also called "ditonic scales", because the largest interval in them is the ditone (e.g., in the scale C–E–F–G–B–C, the interval found between C–E and G–B).[7] This should not be confused with the identical term also used by musicologists to describe a scale including only two notes.

Major pentatonic scale

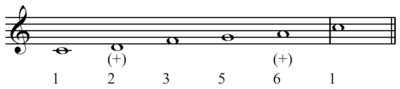

Anhemitonic pentatonic scales can be constructed in many ways. The major pentatonic scale may be thought of as a gapped or incomplete major scale.[8] However, the pentatonic scale has a unique character and is complete in terms of tonality. One construction takes five consecutive pitches from the circle of fifths;[9] starting on C, these are C, G, D, A, and E. Transposing the pitches to fit into one octave rearranges the pitches into the major pentatonic scale: C, D, E, G, A.

Another construction works backward: It omits two pitches from a diatonic scale. If one were to begin with a C major scale, for example, one might omit the fourth and the seventh scale degrees, F and B. The remaining notes then makes up the major pentatonic scale: C, D, E, G, and A.

Omitting the third and seventh degrees of the C major scale obtains the notes for another transpositionally equivalent anhemitonic pentatonic scale: F, G, A, C, D. Omitting the first and fourth degrees of the C major scale gives a third anhemitonic pentatonic scale: G, A, B, D, E.

The black keys on a piano keyboard comprise a G-flat major (or equivalently, F-sharp major) pentatonic scale: G-flat, A-flat, B-flat, D-flat, and E-flat, which is exploited in Chopin's black key étude.

Minor pentatonic scale

Although various hemitonic pentatonic scales might be called minor, the term is most commonly applied to the relative minor pentatonic derived from the major pentatonic, using scale tones 1, 3, 4, 5, and 7 of the natural minor scale.[1] It may also be considered a gapped blues scale.[10] The C minor pentatonic is C, E-flat, F, G, B-flat. The A minor pentatonic, the relative minor of C, comprises the same tones as the C major pentatonic, starting on A, giving A, C, D, E, G. This minor pentatonic contains all three tones of an A minor triad.

Japanese scale

Japanese mode is based on Phrygian mode, but use scale tones 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 instead of scale tones 1, 3, 4, 5, and 7.

The pentatonic scales found by running up the keys C, D, E, G and A

The five pentatonic scales found by running up the keys C, D, E, G and A are:

| Tonic | Name(s) | Based on mode (Diatonic scale) | Base scale degrees (modifications) |

Chinese pentatonic scale | On C | Keys on C-major pentatonic scale | Black keys (the keys on G♭-major pentatonic scale) | Ratios (just) | White-key transpositions (the keys on C-major, F-major and G-major pentatonic scale) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (C) | Major pentatonic | Ionian mode | Major heptatonic I-II-III-V-VI (Omit 4 7) |

宮 (gong, C) mode | C D E G A C | C D E G A C | G♭-A♭-B♭-D♭-E♭-G♭ | 24:27:30:36:40:48 | C D E G A C F G A C D F or G A B D E G |

| 2 (D) | Egyptian, suspended | Dorian mode | Natural minor I-II-IV-V-VII (Omit 3 6) |

商 (shang, D) mode | C D F G B♭ C | D E G A C D | A♭-B♭-D♭-E♭-G♭-A♭ | 24:27:32:36:42:48 | D E G A C D G A C D F G or A B D E G A |

| 3 (E) | Blues minor, Man Gong (慢宮調) | Phrygian mode | Natural minor I-III-IV-VI-VII (Omit 2 5) |

角 (jue, E) mode | C E♭ F A♭ B♭ C | E G A C D E | B♭-D♭-E♭-G♭-A♭-B♭ | 15:18:20:24:27:30 | E G A C D E A C D F G A or B D E G A B |

| 5 (G) | Blues major, Ritsusen (律旋), yo scale | Mixolydian mode | Major heptatonic I-II-IV-V-VI (Omit 3 7) |

徵 (zhi, G) mode | C D F G A C | G A C D E G | D♭-E♭-G♭-A♭-B♭-D♭ | 24:27:32:36:40:48 | G A C D E G C D F G A C or D E G A B D |

| 6 (A) | Minor pentatonic | Aeolian mode | Natural minor I-III-IV-V-VII (Omit 2 6) |

羽 (yu, A) mode | C E♭ F G B♭ C | A C D E G A | E♭-G♭-A♭-B♭-D♭-E♭ | 30:36:40:45:54:60 | A C D E G A D F G A C D or E G A B D E |

(A minor seventh can be 7:4, 16:9, or 9:5; a major sixth can be 27:16 or 5:3. Both were chosen to minimize ratio parts.)

Ricker assigned the major pentatonic scale mode I while Gilchrist assigned it mode III.[11]

Pythagorean tuning

Ben Johnston gives the following Pythagorean tuning for the minor pentatonic scale:[12]

| Note | Solfege | A | C | D | E | G | A | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio | 1⁄1 | 32⁄27 | 4⁄3 | 3⁄2 | 16⁄9 | 2⁄1 | |||||||

| Natural | 54 | 64 | 72 | 81 | 96 | 108 | |||||||

| Audio | |||||||||||||

| Step | Name | m3 | T | T | m3 | T | |||||||

| Ratio | 32⁄27 | 9⁄8 | 9⁄8 | 32⁄27 | 9⁄8 | ||||||||

Naturals in that table are not the alphabetic series A to G without sharps and flats: Naturals are reciprocals of terms in the Harmonic series (mathematics), which are in practice multiples of a fundamental frequency. This may be derived by proceeding with the principle that historically gives the Pythagorean diatonic and chromatic scales, stacking perfect fifths with 3:2 frequency proportions (C–G–D–A–E). Considering the anhemitonic scale as a subset of a just diatonic scale, it is tuned thus: 20:24:27:30:36 (A–C–D–E–G = 5⁄3–1⁄1–9⁄8–5⁄4–3⁄2). Assigning precise frequency proportions to the pentatonic scales of most cultures is problematic as tuning may be variable.

For example, the slendro anhemitonic scale and its modes of Java and Bali are said to approach, very roughly, an equally-tempered five-note scale,[15] but their tunings vary dramatically from gamelan to gamelan.[16]

Composer Lou Harrison has been one of the most recent proponents and developers of new pentatonic scales based on historical models. Harrison and William Colvig tuned the slendro scale of the gamelan Si Betty to overtones 16:19:21:24:28 [17] (1⁄1–19⁄16–21⁄16–3⁄2–7⁄4). They tuned the Mills gamelan so that the intervals between scale steps are 8:7–7:6–9:8–8:7–7:6[18] (1⁄1–8⁄7–4⁄3–3⁄2–12⁄7–2⁄1 = 42:48:56:63:72)

Use of pentatonic scales

Pentatonic scales occur in many musical traditions:

- Peruvian Chicha cumbia

- Indigenous ethnic Folk music of Assam

- Sudanese Arab Music

- Celtic folk music[19]

- English folk music[20]

- German folk music[21]

- Nordic folk music[22]

- Hungarian folk music[23]

- Croatian folk music[23]

- Berber music[24]

- West African music[25]

- African-American spirituals[26]

- Gospel music[27]

- Bluegrass music[28]

- American folk music[29]

- Music of Ethiopia[25]

- Jazz[30]

- Blues[31]

- Rock music[32]

- Sami joik singing[33]

- Children's song[34]

- The music of ancient Greece[35][36]

- Greek traditional music and polyphonic songs from Epirus in northwest Greece[37]

- Music of southern Albania[38]

- Folk songs of peoples of the Middle Volga region (such as the Mari, the Chuvash and Tatars)[39]

- The tuning of the Ethiopian krar[25] and the Indonesian gamelan[40]

- Philippine kulintang[41]

- Native American music, especially in highland South America (the Quechua and Aymara),[42] as well as among the North American Indians of the Pacific Northwest

- Most Turkic,[43] Mongolic and Tungusic music of Siberia and the Asiatic steppe is written in the pentatonic scale

- Melodies of China, Korea, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, Japan, and Vietnam (including the folk music of these countries)

- Andean music[44]

- Afro-Caribbean music[45]

- Polish highlanders from the Tatra Mountains[46]

- Western Impressionistic composers such as French composer Claude Debussy.[47]

In classical music

Examples of its use include Chopin's Etude in G-flat major, op. 10, no. 5, the "Black Key" etude,[1] in the major pentatonic.

Further pentatonic musical traditions

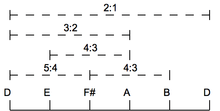

The major pentatonic scale is the basic scale of the music of China and the music of Mongolia as well as many Southeast Asian musical traditions such as that of the Karen people as well as the indigenous Assamese ethnic groups. The fundamental tones (without meri or kari techniques) rendered by the five holes of the Japanese shakuhachi flute play a minor pentatonic scale. The yo scale used in Japanese shomyo Buddhist chants and gagaku imperial court music is an anhemitonic pentatonic scale[48] shown below, which is the fourth mode of the major pentatonic scale.

D Yo scale |

Javanese

Ethiopian

Ethiopian music uses a distinct modal system that is pentatonic, with characteristically long intervals between some notes. As with many other aspects of Ethiopian culture and tradition, tastes in music and lyrics are strongly linked with those in neighboring Eritrea, Somalia, Djibouti and Sudan.[50][51]

Scottish

In Scottish music, the pentatonic scale is very common. Seumas MacNeill suggests that the Great Highland bagpipe scale with its augmented fourth and diminished seventh is "a device to produce as many pentatonic scales as possible from its nine notes" (although these two features are not in the same scale).[52] Roderick Cannon explains these pentatonic scales and their use in more detail, both in Piobaireachd and light music.[53] It also features in Irish traditional music, either purely or almost so. The minor pentatonic is used in Appalachian folk music. Blackfoot music most often uses anhemitonic tetratonic or pentatonic scales.[54]

Andean

In Andean music, the pentatonic scale is used substantially minor, sometimes major, and seldom in scale. In the most ancient genres of Andean music being performed without string instruments (only with winds and percussion), pentatonic melody is often leaded with parallel fifths and fourths, so formally this music is hexatonic. Hear example:

Jazz

Jazz music commonly uses both the major and the minor pentatonic scales. Pentatonic scales are useful for improvisers in modern jazz, pop, and rock contexts because they work well over several chords diatonic to the same key, often better than the parent scale. For example, the blues scale is predominantly derived from the minor pentatonic scale, a very popular scale for improvisation in the realms of blues and rock alike.[55] ![]()

Other

U.S. military cadences, or jodies, which keep soldiers in step while marching or running, also typically use pentatonic scales.[56]

Hymns and other religious music sometimes use the pentatonic scale; for example, the melody of the hymn "Amazing Grace",[57] one of the most famous pieces in religious music.

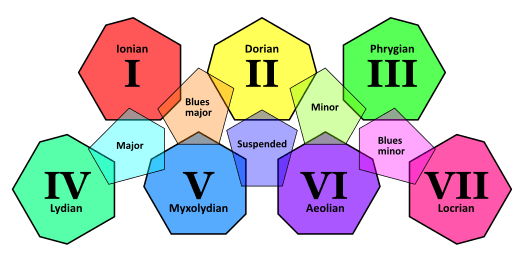

The common pentatonic major and minor scales (C-D-E-G-A and C-E♭-F-G-B♭, respectively) are useful in modal composing, as both scales allow a melody to be modally ambiguous between their respective major (Ionian, Lydian, Mixolydian) and minor (Aeolian, Phrygian, Dorian) modes (Locrian excluded). With either modal or non-modal writing, however, the harmonization of a pentatonic melody does not necessarily have to be derived from only the pentatonic pitches.

Role in education

The pentatonic scale plays a significant role in music education, particularly in Orff-based, Kodály-based, and Waldorf methodologies at the primary or elementary level.

The Orff system places a heavy emphasis on developing creativity through improvisation in children, largely through use of the pentatonic scale. Orff instruments, such as xylophones, bells and other metallophones, use wooden bars, metal bars or bells, which can be removed by the teacher, leaving only those corresponding to the pentatonic scale, which Carl Orff himself believed to be children's native tonality.[58]

Children begin improvising using only these bars, and over time, more bars are added at the teacher's discretion until the complete diatonic scale is being used. Orff believed that the use of the pentatonic scale at such a young age was appropriate to the development of each child, since the nature of the scale meant that it was impossible for the child to make any real harmonic mistakes.[59]

In Waldorf education, pentatonic music is considered to be appropriate for young children due to its simplicity and unselfconscious openness of expression. Pentatonic music centered on intervals of the fifth is often sung and played in early childhood; progressively smaller intervals are emphasized within primarily pentatonic as children progress through the early school years. At around nine years of age the music begins to center on first folk music using a six-tone scale, and then the modern diatonic scales, with the goal of reflecting the children's developmental progress in their musical experience. Pentatonic instruments used include lyres, pentatonic flutes, and tone bars; special instruments have been designed and built for the Waldorf curriculum.[60]

See also

References

- Bruce Benward and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2003), Music: In Theory and Practice, seventh edition (Boston: McGraw Hill), vol. I, p. 37. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- Bruce Benward and Marilyn Nadine Saker, Music in Theory and Practice, eighth edition (Boston: McGraw Hill, 2009): vol. II, p. 245. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

- John Powell (2010). How Music Works: The Science and Psychology of Beautiful Sounds, from Beethoven to the Beatles and Beyond. New York: Little, Brown and Company. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-316-09830-4.

- Susan Miyo Asai (1999). Nōmai Dance Drama, p. 126. ISBN 978-0-313-30698-3.

- Minoru Miki, Marty Regan, Philip Flavin (2008). Composing for Japanese instruments, p. 2. ISBN 978-1-58046-273-0.

- Jeff Todd Titon (1996). Worlds of Music: An Introduction to the Music of the World's Peoples, Shorter Version. Boston: Cengage Learning. ISBN 9780028726120. page 373.

- Anon., "Ditonus", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001); Bence Szabolcsi, "Five-Tone Scales and Civilization", Acta Musicologica 15, nos. 1–4 (January–December 1943): pp. 24–34, citation on p. 25.

- Benward & Saker (2003), p. 36.

- Paul Cooper, Perspectives in Music Theory: An Historical-Analytical Approach(New York: Dodd, Mead, 1973), p. 18. . ISBN 0-396-06752-2.

- Steve Khan (2002). Pentatonic Khancepts. Alfred Music Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7579-9447-0. p. 12.

- Ramon Ricker (1999). Pentatonic Scales for Jazz Improvisation. Lebanon, Ind.: Studio P/R, Alfred Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1-4574-9410-9. cites Annie G. Gilchrist (1911). "Note on the Modal System of Gaelic Tunes". Journal of the Folk-Song Society. 4 (16): 150–53. JSTOR 4433969. – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Ben Johnston, "Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource", Perspectives of New Music 2, no. 2 (Spring–Summer 1964): pp. 56–76. Citation on p. 64 . (subscription required) Accessed 4 January 2009.

- Leta E. Miller and Fredric Lieberman (Summer 1999). "Lou Harrison and the American Gamelan", p. 158, American Music, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 146–78.

- "The representations of slendro and pelog tuning systems in Western notation shown above should not be regarded in any sense as absolute. Not only is it difficult to convey non-Western scales with Western notation ..." Jennifer Lindsay, Javanese Gamelan (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), pp. 39–41. ISBN 0-19-588582-1.

- Lindsay (1992), p. 38–39: "Slendro is made up of five equal, or relatively equal, intervals".

- "... in general, no two gamelan sets will have exactly the same tuning, either in pitch or in interval structure. There are no Javanese standard forms of these two tuning systems." Lindsay (1992), pp. 39–41.

- Miller & Lieberman (1999), p. 159.

- Miller & Lieberman (1999), p. 161.

- June Skinner Sawyers (2000). Celtic Music: A Complete Guide. [United States]: Da Capo Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-306-81007-7.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: location (link)

- Ernst H. Meyer, Early English Chamber Music: From the Middle Ages to Purcell, second edition, edited by Diana Poulton (Boston: Marion Boyars Publishers, Incorporated, 1982): p. 48. ISBN 9780714527772.

- Judit Frigyesi (2013). Is there such a thing as Hungarian-Jewish music? In Pál Hatos & Attila Novák (Eds.) (2013). Between Minority and Majority: Hungarian and Jewish/Israeli ethnical and cultural experiences in recent centuries. Budapest: Balassi Institute. page 129. ISBN 978-963-89583-8-9.

- Blacking, John (November 1987). "A commonsense view of all music" : reflections on Percy Grainger's contribution to ethnomusicology and music education. Cambridge University Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780521265003. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Benjamin Suchoff, ed. (1997). Béla Bartók Studies in Ethnomusicology. Lincoln: U of Nebraska Press. p. 198. ISBN 0-8032-4247-6.

- Alwan For The Arts.

- Richard Henry (n.d.). Culture and the Pentatonic Scale: Exciting Information On Pentatonic Scales. n.p.: World Wide Jazz. p. 4.

- Erik Halbig (2005). Pentatonic Improvisation: Modern Pentatonic Ideas for Guitarists of All Styles, Book & CD. Van Nuys, CA.: Alfred Music Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7390-3765-2.

- Lenard C. Bowie, DMA (2012). AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSICAL HERITAGE: An Appreciation, Historical Summary, and Guide to Music Fundamentals. Philadelphia: Xlibris Corporation. p. 259. ISBN 978-1-4653-0575-6.

- Jesper Rübner-Petersen (2011). The Mandolin Picker's Guide to Bluegrass Improvisation. Pacific, MO.: Mel Bay Publications. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-61065-413-5.

- William Duckworth (2009). A Creative Approach to Music Fundamentals. Boston: Schirmer / Cengage Learning. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-111-78406-5.

- Kurt Johann Ellenberger (2005). Materials and Concepts in Jazz Improvisation. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Keystone Publication / Assayer Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-9709811-3-4.

- Edward Komara, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Blues. New York: Routledge. p. 863. ISBN 978-0-415-92699-7.

- Joe Walker (6 January 2012). "The World's Most-Used Guitar Scale: A Minor Pentatonic". DeftDigits Guitar Lessons.

- Kathryn Burke. "The Sami Yoik". Sami Culture.

- Jeremy Day-O'Connell (2007). Pentatonicism from the Eighteenth Century to Debussy. Rochester: University Rochester Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-58046-248-8.

- M. L. West (1992). Ancient Greek Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 163–64. ISBN 0198149751.

- A.-F. Christidis; Maria Arapopoulou; Maria Christi (2007). A History of Ancient Greek: From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1432. ISBN 978-0-521-83307-3.

- Meri-Sofia Lakopoulos (2015). The Traditional Iso-polyphonic song of Epirus. The International Research Center for Traditional Polyphony. June 2015, Issue 18. p.10.

- Spiro J. Shetuni (2011). Albanian Traditional Music: An Introduction, with Sheet Music and Lyrics for 48 Songs. Jefferson, N. C.: McFarland. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7864-8630-4.

- Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. London: Rough Guides. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8.

- Mark Phillips (2002). GCSE Music. Oxford: Heinemann. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-435-81318-5.

- Willi Apel (1969). Harvard Dictionary of Music. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 665. ISBN 978-0-674-37501-7.

- Carmen Bernand (19 August 2009). "Musiques métisses, musiques populaires, musiques latines: genèse coloniale, identités républicaines et globalisation". Sorbonne University. France. 6 (11): 87–106. ISSN 1794-5887.

- Qian, Gong (19 June 1995). "A Common Denominator Music Links Ethnic Chinese with Hungarians". China Daily – via ProQuest.

- Dale A. Olsen; Daniel E. Sheehy, eds. (1998). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2: South America, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 217. ISBN 0824060407. (Thomas Turino (2004) points out that the pentatonic scale, although widespread, cannot be considered to be predominant in the Andes: Local practices among the Aymara and Kechua in Conima and Canas, Southern Peru in Malena Kuss, ed. (2004). Music in Latin America and the Caribbean: an encyclopedic history. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 141. ISBN 0292702981.)

- Burton William Peretti (2009). Lift Every Voice: The History of African American Music. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-7425-5811-3.

- Anna Czekanowska; John Blacking (2006). Polish Folk Music: Slavonic Heritage - Polish Tradition - Contemporary Trends. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-521-02797-7.

- Jeremy Day-O'Connell (2009). "Debussy, Pentatonicism, and the Tonal Tradition" (PDF). Music Theory Spectrum. 31 (2): 225–261. doi:10.1525/mts.2009.31.2.225.

- Japanese Music, Cross-Cultural Communication: World Music, University of Wisconsin – Green Bay.

- Sumarsam (1988) Introduction to Javanese Gamelan.

- Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi (2001). Culture and Customs of Somalia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 170. ISBN 0-313-31333-4.

Somali music, a unique kind of music that might be mistaken at first for music from nearby countries such as Ethiopia, the Sudan, or even Arabia, can be recognized by its own tunes and styles.

- Tekle, Amare (1994). Eritrea and Ethiopia: from conflict to cooperation. The Red Sea Press. p. 197. ISBN 0-932415-97-0.

Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan have significant similarities emanating not only from culture, religion, traditions, history and aspirations[...] They appreciate similar foods and spices, beverages and sweets, fabrics and tapestry, lyrics and music, and jewelry and fragrances.

- Seumas MacNeil and Frank Richardson Piobaireachd and its Interpretation (Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd, 1996): p. 36. ISBN 0-85976-440-0

- Roderick D. Cannon The Highland Bagpipe and its Music (Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd, 1995): pp. 36–45. ISBN 0-85976-416-8

- Bruno Nettl, Blackfoot Musical Thought: Comparative Perspectives (Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1989): p. 43. ISBN 0-87338-370-2.

- "The Pentatonic and Blues Scale". How To Play Blues Guitar. 2008-07-09. Archived from the original on 2008-07-14. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- "NROTC Cadences". Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- Steve Turner, Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song (New York: HarperCollins, 2002): p. 122. ISBN 0-06-000219-0.

- Beth Landis; Polly Carder (1972). The Eclectic Curriculum in American Music Education: Contributions of Dalcroze, Kodaly, and Orff. Washington D.C.: Music Educators National Conference. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-940796-03-4.

- Amanda Long. "Involve Me: Using the Orff Approach within the Elementary Classroom". The Keep. Eastern Illinois University. p. 7. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- Andrea Intveen, Musical Instruments in Anthroposophical Music Therapy with Reference to Rudolf Steiner’s Model of the Threefold Human Being Archived 2012-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Jeremy Day-O'Connell, Pentatonicism from the Eighteenth Century to Debussy (Rochester: University of Rochester Press 2007) – the first comprehensive account of the increasing use of the pentatonic scale in 19th-century Western art music, including a catalogue of over 400 musical examples.

- Trần Văn Khê, "Le pentatonique est-il universel? Quelques reflexions sur le pentatonisme", The World of Music 19, nos. 1–2:85–91 (1977). English translation: "Is the pentatonic universal? A few reflections on pentatonism" pp. 76–84. – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Kurt Reinhard, "On the problem of pre-pentatonic scales: particularly the third-second nucleus", Journal of the International Folk Music Council 10 (1958). – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Yamaguchi Masaya (New York: Charles Colin, 2002; New York: Masaya Music, Revised 2006). Pentatonicism in Jazz: Creative Aspects and Practice. ISBN 0-9676353-1-4

- Jeff Burns, Pentatonic Scales for the Jazz-Rock Keyboardist (Lebanon, Ind.: Houston Publishing, 1997). ISBN 978-0-7935-7679-1.

External links

| Look up pentatonic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |