Pareidolia

Pareidolia (/pærɪˈdoʊliə/ parr-i-DOH-lee-ə) is the tendency for incorrect perception of a stimulus as an object, pattern or meaning known to the observer, such as seeing shapes in clouds, seeing faces in inanimate objects or abstract patterns, or hearing hidden messages in music. Pareidolia can be considered a subcategory of apophenia.

Common examples are perceived images of animals, faces, or objects in cloud formations, the Man in the Moon, the Moon rabbit, and other lunar pareidolia. The concept of pareidolia may extend to include hidden messages in recorded music played in reverse or at higher- or lower-than-normal speeds, and hearing indistinct voices in random noise such as that produced by air conditioners or fans.[1]

Pareidolia was at one time considered a symptom of human psychosis, but it is now seen as a normal human tendency.[2]

Pareidolia is not confined to humans. Scientists have for years taught computers to use visual clues to "see" faces and other images.[2]

Etymology

The word derives from the Greek words para (παρά, "beside, alongside, instead [of]") and the noun eidōlon (εἴδωλον "image, form, shape").[2]

The German word pareidolie was used in German articles by Dr. Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum — for example in his 1866 paper "On Delusion of the Senses". When Kahlbaum's paper was reviewed the following year (1867) in The Journal of Mental Science, Volume 13, pareidolie was translated as pareidolia: "…partial hallucination, perception of secondary images, or pareidolia."[3]

Explanations

Pareidolia can cause people to interpret random images, or patterns of light and shadow, as faces.[4] A 2009 magnetoencephalography study found that objects perceived as faces evoke an early (165 ms) activation of the fusiform face area at a time and location similar to that evoked by faces, whereas other common objects do not evoke such activation. This activation is similar to a slightly faster time (130 ms) that is seen for images of real faces. The authors suggest that face perception evoked by face-like objects is a relatively early process, and not a late cognitive reinterpretation phenomenon.[5] A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study in 2011 similarly showed that repeated presentation of novel visual shapes that were interpreted as meaningful led to decreased fMRI responses for real objects. These results indicate that the interpretation of ambiguous stimuli depends upon processes similar to those elicited by known objects.[6]

These studies help to explain why people identify a few lines and a circle as a "face" so quickly and without hesitation. Cognitive processes are activated by the "face-like" object, which alert the observer to both the emotional state and identity of the subject, even before the conscious mind begins to process or even receive the information. A "stick figure face", despite its simplicity, can convey mood information, and be drawn to indicate emotions such as happiness or anger. This robust and subtle capability is hypothesized to be the result of eons of natural selection favoring people most able to quickly identify the mental state, for example, of threatening people, thus providing the individual an opportunity to flee or attack pre-emptively. In other words, processing this information subcortically – therefore subconsciously – before it is passed on to the rest of the brain for detailed processing accelerates judgment and decision making when a fast reaction is needed.[7] This ability, though highly specialized for the processing and recognition of human emotions, also functions to determine the demeanor of wildlife.[8]

Pareidolia can be considered a subcategory of apophenia.

Mimetoliths

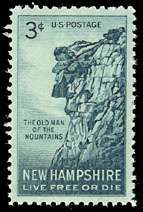

Rocks may come to mimic recognizable forms through the random processes of formation, weathering and erosion.

Picture jaspers exhibit combinations of patterns such as banding from flow or depositional patterns (from water or wind), or dendritic or color variations, resulting in what appear to be miniature scenes on a cut section, which is then used for jewelry.

More often, the size scale of the rock is larger than the object it resembles, such as a cliff profile resembling a human face. Well-meaning people with a new interest in fossils can pick up chert nodules, concretions or pebbles resembling bones, skulls, turtle shells, dinosaur eggs, etc., in both size and shape.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Japanese researcher Chonosuke Okamura self-published a series of reports titled Original Report of the Okamura Fossil Laboratory, in which he described tiny inclusions in polished limestone from the Silurian period (425 mya) as being preserved fossil remains of tiny humans, gorillas, dogs, dragons, dinosaurs and other organisms, all of them only millimeters long, leading him to claim, "There have been no changes in the bodies of mankind since the Silurian period... except for a growth in stature from 3.5 mm to 1,700 mm."[9][10] Okamura's research earned him an Ig Nobel Prize (a parody of the Nobel Prizes) in biodiversity in 1996.[11][12]

Projective tests

The Rorschach inkblot test uses pareidolia in an attempt to gain insight into a person's mental state. The Rorschach is a projective test, as it intentionally elicits the thoughts or feelings of respondents that are "projected" onto the ambiguous inkblot images.[13]

Literature and art

Renaissance artists and authors have shown a particular interest in pareidolia. In William Shakespeare's play Hamlet, for example, the character Hamlet points at the sky and "demonstrates" his supposed madness in this exchange with Polonius:

HAMLET

Do you see yonder cloud that’s almost in the shape of a camel?

POLONIUS

By th’Mass and ’tis, like a camel indeed.

HAMLET

Methinks it is a weasel.

POLONIUS

It is backed like a weasel.

HAMLET

Or a whale.

POLONIUS

Very like a whale.<ref>Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. 3.3.367-73</ref><ref>Raber, Karen. Shakespeare and Posthumanist Theory. Arden Shakespeare (2018) pp. 80-1 ISBN 978-1474234436</ref>

Graphic artists have often used pareidolia in paintings and drawings: Andrea Mantegna, Leonardo Da Vinci, Giotto, Hans Holbein, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, and many more have shown images—often human faces—that due to pareidolia appear in objects or clouds.[14]

In his notebooks, Leonardo da Vinci wrote of pareidolia as a device for painters, writing:

If you look at any walls spotted with various stains or with a mixture of different kinds of stones, if you are about to invent some scene you will be able to see in it a resemblance to various different landscapes adorned with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, plains, wide valleys, and various groups of hills. You will also be able to see divers combats and figures in quick movement, and strange expressions of faces, and outlandish costumes, and an infinite number of things which you can then reduce into separate and well conceived forms.[15]

In The Mercy Seat (song) by Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds, the condemned man has mixed feelings about his pareidolic experiences :

I began to warm and chill

To objects and their fields

A ragged cup, a twisted mop

The face of Jesus in my soup

Architecture

Two 13th-century edifices in Turkey display architectural use of shadows of stone carvings at the entrance. Outright pictures are avoided in Islam but tessellations and calligraphic pictures were allowed, so designed "accidental" silhouettes of carved stone tessellations became a creative escape.

- Niğde Alaaddin Mosque, Niğde, Turkey (1223) with its "mukarnas" art where the shadows of three-dimensional ornamentation with stone masonry around the entrance form a chiaroscuro drawing of a woman's face with a crown and long hair appearing at a specific time, at some specific days of the year.[16][17][18]

- Divriği Great Mosque and Hospital in Sivas, Turkey (1229) shows shadows of the 3 dimensional ornaments of both entrances of the mosque part, to cast a giant shadow of a praying man that changes pose as the sun moves, as if to illustrate what the purpose of the building is. Another detail is the difference in the impressions of the clothing of the two shadow-men indicating two different styles, possibly to tell who is to enter through which door.[19]

Religious

There have been many instances of perceptions of religious imagery and themes, especially the faces of religious figures, in ordinary phenomena. Many involve images of Jesus,[13] the Virgin Mary,[20] the word Allah,[21] or other religious phenomena: in September 2007 in Singapore, for example, a callus on a tree resembled a monkey, leading believers to pay homage to the "Monkey god" (either Sun Wukong or Hanuman) in the monkey tree phenomenon.[22]

Publicity surrounding sightings of religious figures and other surprising images in ordinary objects has spawned a market for such items on online auctions like eBay. One famous instance was a grilled cheese sandwich with the face of the Virgin Mary.[23]

During the September 11 attacks, television viewers supposedly saw the face of Satan in clouds of smoke billowing out of the World Trade Center after it was struck by the airplane.[24] Another example of face recognition pareidolia originated in the fire at Notre Dame Cathedral, when a few observers claimed to see Jesus in the flames.[25]

Mars canals

A notable example of pareidolia occurred in 1877, when observers using telescopes to view the surface of Mars thought that they saw faint straight lines, which were then interpreted by some as canals (see Martian canal). It was theorized that the canals were possibly created by sentient beings. This created a sensation. In the next few years better photographic techniques and stronger telescopes were developed and applied, which resulted in new images in which the faint lines disappeared, and the canal theory was debunked as an example of pareidolia.[26][27]

Computer vision

.jpg)

Pareidolia can occur in computer vision,[28] specifically in image recognition programs, in which vague clues can spuriously detect images or features. In the case of an artificial neural network, higher-level features correspond to more recognizable features, and enhancing these features brings out what the computer sees. These examples of pareidolia reflect the training set of images that the network has "seen" previously.

Striking visuals can be produced in this way, notably in the DeepDream software, which falsely detects and then exaggerates features such as eyes and faces in any image.

Speech

In 1971 Konstantīns Raudive wrote Breakthrough, detailing what he believed was the discovery of electronic voice phenomena (EVP). EVP has been described as auditory pareidolia.[13] Allegations of backmasking in popular music, in which a listener claims a message has been recorded backward onto a track meant to be played forward, have also been described as auditory pareidolia.[13][29] In 1995, the psychologist Diana Deutsch invented an algorithm for producing phantom words and phrases with the sounds coming from two stereo loudspeakers, with one to the listener's left and the other to his right. Each loudspeaker produces a phrase consisting of two words or syllables. The same sequence is presented repeatedly through both loudspeakers; however, they are offset in time so that when the first sound (word or syllable) is coming from the speaker on the left, the second sound is coming from the speaker on the right, and vice versa. After listening for a while, phantom words and phrases suddenly emerge, and these often appear to reflect what is on the listener's mind, and they transform perceptually into different words and phrases as the sequence continues.[30][31]

Related phenomena

A shadow person (also known as a shadow figure, shadow being or black mass) is often attributed to pareidolia. It is the perception of a patch of shadow as a living, humanoid figure, particularly as interpreted by believers in the paranormal or supernatural as the presence of a spirit or other entity.[32]

Pareidolia is also what some skeptics believe causes people to believe that they have seen ghosts.[33]

Examples

The Romanian Sphinx in Bucegi Mountains

The Romanian Sphinx in Bucegi Mountains A smiling face on part of a military jet

A smiling face on part of a military jet

A face in furniture drawers

A face in furniture drawers A Samurai Crab has a shell that bears a pattern resembling the face of an angry Samurai warrior

A Samurai Crab has a shell that bears a pattern resembling the face of an angry Samurai warrior- "Elephant Rock" on Heimaey, Iceland

"Monument to Humanity", Marcahuasi

"Monument to Humanity", Marcahuasi.jpg) In a work by Wenceslas Hollar a landscape appears to resemble the head of a man lying on his back.

In a work by Wenceslas Hollar a landscape appears to resemble the head of a man lying on his back.

See also

References

- Jaekel, Philip (2017-01-29). "Why we hear voices in random noise". Nautilus. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- Rosen, Rebecca J. "Pareidolia: A Bizarre Bug of the Human Mind Emerges in Computers". The Atlantic. August 7, 2012.

- Sibbald, M.D. "Report on the Progress of Psychological Medicine; German Psychological Literature", The Journal of Mental Science, Volume 13. 1867. p. 238

- Sagan, Carl (1995). The Demon-Haunted World – Science as a Candle in the Dark. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-53512-8.

- Hadjikhani, Nouchine; Kveraga, Kestutis; Naik, Paulami; Ahlfors, Seppo P. (2009). "Early (M170) activation of face-specific cortex by face-like objects". NeuroReport. 20 (4): 403–07. doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e328325a8e1. PMC 2713437. PMID 19218867.

- Voss, J. L.; Federmeier, K. D.; Paller, K. A. (2012). "The Potato Chip Really Does Look Like Elvis! Neural Hallmarks of Conceptual Processing Associated with Finding Novel Shapes Subjectively Meaningful". Cerebral Cortex. 22 (10): 2354–64. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhr315. PMC 3432238. PMID 22079921.

- Svoboda, Elizabeth (2007-02-13). "Facial Recognition – Brain – Faces, Faces Everywhere". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- "Dog Tips – Emotions in Canines and Humans". Partnership for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- Spamer, E. "Chonosuke Okamura, Visionary". Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences. Archived from the original on 2015-11-18. Retrieved 2008-08-11. archived at Improbable Research.

- Berenbaum, May (2009). The earwig's tail: a modern bestiary of multi-legged legends. Harvard University Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-674-03540-9.

- Abrahams, Marc (2004-03-16). "Tiny tall tales: Marc Abrahams uncovers the minute, but astonishing, evidence of our fossilised past". The Guardian. London.

- Conner, Susan; Kitchen, Linda (2002). Science's most wanted: the top 10 book of outrageous innovators, deadly disasters, and shocking discoveries. Most Wanted. Brassey's. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-57488-481-4.

- Zusne, Leonard; Jones, Warren H (1989). Anomalistic Psychology: A Study of Magical Thinking. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-8058-0508-6. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- Raber, Karen. Shakespeare and Posthumanist Theory. Arden Shakespeare (2018) pp. 81-2 ISBN 978-1474234436

- Da Vinci, Leonardo (1923). John, R; Don Read, J (eds.). "Note-Books Arranged And Rendered Into English". Empire State Book Co.

- "Niğde Alaaddin Camii 'nin Kapısındaki Kadın Silüetinin Sırrı?". Nevşehir Kentrehberim (in Turkish). 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Camiler, ALÂEDDİN CAMİ". Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı (in Turkish). Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "HISTORICAL MONUMENTS OF NIGDE". World Heritage Academy. 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "DİVRİĞİ ULU CAMİİ'NDE 'NAMAZ KILAN İNSAN' SİLÜETİ". Haberler (in Turkish). 14 July 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Schweber, Nate (July 23, 2012). "In New Jersey, a Knot in a Tree Trunk Draws the Faithful and the Skeptical". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. p. 16. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Ibrahim, Yahaya (2 January 2011). "In Maiduguri, a tree with engraved name of God turns spot to a Mecca of sorts". Sunday Trust. Abuja. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- Ng, Hui Hui (13 September 2007). "Monkey See, Monkey Do?". The New Paper. Singapore Press Holdings Ltd. Co. pp. 12–13. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "'Virgin Mary' toast fetches $28,000". BBC News. BBC. 23 November 2004. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- Emery, David (2 September 2018). "Does the Devil's Face Appear in the Smoke on 9/11?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Moye, David (April 17, 2019). "People Claim To See Jesus In Flames Engulfing Notre Dame Cathedral". Huffington Post. Verizon Media. Retrieved 21 April 2019 – via Yahoo! Lifestyle.

- Kitchin, C. R. Astrophysical Techniques, Sixth Edition. Taylor & Francis (2013). ISBN 9781466511156 p. 3

- Lane, K. Maria. Geographies of Mars: Seeing and Knowing the Red Planet. University of Chicago Press (2011). p. 52-63. ISBN 9780226470788

- Chalup, Stephan K., Kenny Hong, and Michael J. Ostwald. "Simulating pareidolia of faces for architectural image analysis." brain 26.91 (2010): 100.

- Vokey, John R.; Read, J. Don (1985). "Subliminal messages: Between the devil and the media". American Psychologist. 40 (11): 1231–9. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.40.11.1231. PMID 4083611.

- Deutsch, D. (1995). "Musical Illusions and Paradoxes". Philomel Records.

- Deutsch, D. (2003). "Phantom Words and Other Curiosities". Philomel Records.

- Ahlquist, Diane (2007). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Life After Death. US: Penguin Group. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-59257-651-7.

- Carroll, Robert Todd (June 2001). "pareidolia". skepdic.com. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

External links

- Skepdic.com Skeptic's Dictionary definition of pareidolia

- A Japanese museum of rocks which look like faces

- Article in The New York Times, 13 February 2007, about cognitive science of face recognition