Oriental magpie

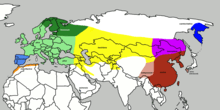

The Oriental magpie (Pica serica) is a species of magpie found from south-eastern Russia and Myanmar to eastern China, Taiwan and northern Indochina. It is also a common symbol of the Korean identity, and has been adopted as the "official bird" of numerous South Korean cities, counties and provinces. Other names for the Oriental magpie include Korean magpie and Asian magpie.[1]

| Oriental magpie | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Adult in Daejon (South Korea) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Pica |

| Species: | P. serica |

| Binomial name | |

| Pica serica Gould, 1845 | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pica pica jankowskii (but see text) | |

Taxonomy and systematics

A recent study comparing 813 bp mtDNA sequences led to the split of the Oriental magpie from the Eurasian magpie. It has been reproductively isolated for longer even than the yellow-billed magpie (P. nuttalli) of North America. Proposed subspecies include P. p. jankowskii and P. p. japonica.[2]

The Oriental magpie's evolution as a distinct lineage started considerably earlier than the Gelasian date of c.2 million years ago (Ma) indicated by a molecular clock analysis. The assumed divergence rate – 1.6% point mutations per Ma – is appropriate for a long-lived passerine, but hybridization – which as only mtDNA was used would be hard to detect – and the few specimens analyzed make the molecular clock estimate just an approximation. Meanwhile, the fossil record of North American magpies has a specimen – UCMP 43386, a left tarsometatarsus from Palo Duro Falls (Randall County, Texas) – which is probably from the Early Pleistocene Irvingtonian age, around 2–1 Ma. It shows the distinct features of a black-billed magpie (P. (p.) hudsonia), though it might be from a common ancestor of black- and yellow-billed magpies. This was not used to calibrate the molecular clock analysis, but accounting for the phylogenetic hypothesis it appears more likely that the Korean magpie's ancestors diverged from other Pica in the Early Pliocene already, perhaps 5–4.5 Ma, antedating the uplift of the Sierra Nevada which cut off most gene flow between the two North American populations. Residual gene flow between them (and between the two (or more?) Eurasian magpie lineages) until the onset of the Quaternary glaciation some 2.6–2 Ma may also have skewed the molecular clock results.[2][3]

Like the other magpies, the Oriental magpie is a member of the large radiation of mainly Holarctic corvids, which also includes the typical crows and ravens (Corvus) nutcrackers (Nucifraga) and Old World jays. The long tail might be plesiomorphic for this group, as it is also found in the tropical Asian magpies (Cissa and Urocissa) as well as in most of the very basal corvids, such as the treepies. The unique black-and-white color pattern of the "monochrome" magpies is an autapomorphy. [4][5]

Description

Compared to the Eurasian magpie, it is somewhat stockier, with a proportionally shorter tail and longer wings. The back, tail, and particularly the remiges show strong purplish-blue iridescence with few if any green hues. They are the largest magpies. They have a rump plumage that is mostly black, with but a few and often hidden traces of the white band which connects the white shoulder patches in their relatives.[1] The Oriental magpie has the same call as the Eurasian magpie, albeit much softer.

In culture

In Korea, the magpie(까치, "kkachi") is celebrated as "a bird of great good fortune, of sturdy spirit and a provider of prosperity and development".[6] Similarly, in China, magpies are seen as an omen of good fortune.[7] This is reflected in the Chinese word for magpie, simplified Chinese: 喜鹊; traditional Chinese: 喜鵲; pinyin: xǐquè, in which the first character means "happiness". It was the official ‘bird of joy’ for the Manchu dynasty.

References

- Bangs, Outram (1932). "Birds of western China obtained by the Kelley-Roosevelts expedition". Field Mus. Nat. Hist. Zool. Ser. 18 (11): 343–379. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.3192.

- Lee, Sang-im; Parr, Cynthia S.; Hwang, Youna; Mindell, David P.; Choe, J.C. (2003). "Phylogeny of magpies (genus Pica) inferred from mtDNA data". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 29 (2): 250–257. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00096-4. PMID 13678680.

- Miller, Alden H.; Bowman, Robert I. (1956). "A Fossil Magpie from the Pleistocene of Texas" (PDF). Condor. 58 (2): 164–165. doi:10.2307/1364980.

- Ericson, Per G.P.; Jansén, Anna-Lee; Johansson, Ulf S.; Ekman, Jan (2005). "Inter-generic relationships of the crows, jays, magpies and allied groups (Aves: Corvidae) based on nucleotide sequence data" (PDF). J. Avian Biol. 36 (3): 222–234. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2001.03409.x.

- Jønsson, Knud A.; Fjeldså, Jon (2006). "A phylogenetic supertree of oscine passerine birds (Aves: Passeri)". Zoologica Scripta. 35 (2): 149–186. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2006.00221.x.

- Winterman, Denise. "Why are magpies so often hated?". BBC News Magazine.

Magpies have a dubious reputation because they are a bit of both. Over the years they have been lumped in with blackbirds

- "春蚕、喜鹊、梅花、百合花有什么象征意义?" [Silkworms, magpie, plum blossom, lily. What symbolic meaning?] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2017-08-31. Retrieved 2018-07-01.

External links