Orbital ring

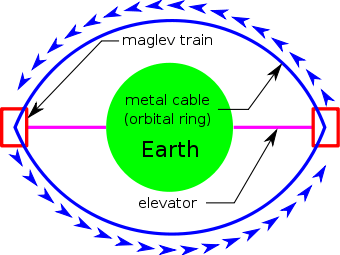

An orbital ring is a concept of an enormous artificial ring placed around the Earth that rotates at an angular rate that is faster than the rotation of the Earth.

The structure is intended to be used as a space station or as a planetary vehicle for very high speed transportation or space launch.

The original orbital ring concept is related to the space fountain, space elevator and launch loop.

History

In the 1870s Nikola Tesla, while recovering from malaria, conceived a number of inventions including a ring around the equator, although he did not include detailed calculations. As recounted in his autobiography My Inventions (1919):

Another one of my projects was to construct a ring around the equator which would, of course, float freely and could be arrested in its spinning motion by reactionary forces, thus enabling travel at a rate of about one thousand miles an hour, impracticable by rail. The reader will smile. The plan was difficult of execution, I will admit, but not nearly so bad as that of a well-known New York professor, who wanted to pump the air from the torrid to the temperate zones, entirely forgetful of the fact that the Lord had provided a gigantic machine for this very purpose.[1]

A simple unsupported hoop about a planet (or a star) is unstable: it would crash into the central body if left unattended.[2][3] The orbital ring concept requires a method of stabilizing the ring.

A more detailed description of the concept was proposed and analyzed by Paul Birch in 1982, proposing a massive ring that would encircle the globe in low orbit, from which cables hang down to the earth's surface.[4][5][6]

In 1982 the Belarusian inventor Anatoly Yunitskiy also proposed an electromagnetic track encircling the Earth, which he called "by wheel into space"[7] (later, "String Transportation System"). When the velocity of the string exceeds 10 km/sec, centrifugal forces detach the string from the Earth's surface and lift the ring into space.

Andrew Meulenberg and his students, from 2008 to 2011, presented and published a number of papers based on types and applications of low-Earth-orbital rings as man's "stepping-stones-to-space". An overview[8] mentions four applications of orbital rings.

Birch's model

Paul Birch published a series of three articles in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society in 1982 that laid out the mathematical basis of ring systems.[4][5][6]

In the simplest design of an orbital ring system, a rotating cable or possibly an inflatable space structure is placed in a low Earth orbit above the equator. Not in orbit, but riding on this ring, supported electromagnetically on superconducting magnets, are ring stations that stay in one place above some designated point on Earth. Hanging down from these ring stations are short elevator cables made from materials with high-tensile-strength-to-mass-ratio.

Although this simple model would work best above the equator, Paul Birch calculated that since the ring station can be used to accelerate the orbital ring eastwards as well as hold the tether, it is therefore possible to deliberately cause the orbital ring to precess around the Earth instead of staying fixed in space while the Earth rotates beneath it. By precessing the ring once every 24 hours, the Orbital Ring will hover above any meridian selected on the surface of the Earth. The cables which dangle from the ring are now geostationary without having to reach geostationary altitude or without having to be placed into the equatorial plane. This means that using the Orbital Ring concept, one or many pairs of Stations can be positioned above any points on Earth desired or can be moved everywhere on the globe. Thus, any point on Earth can be served by a space elevator. Also a whole network of orbital rings can be built, which, by crossing over the poles, could cover the whole planet and be capable of taking over most of freight and passenger transport. By an array of elevators and several geostationary ring stations, asteroid or Moon material can be received and gently put down where land fills are needed. The electric energy generated in the process would pay for the system expansion and ultimately could pave the way for a solar-system-wide terraforming- and astroengineering-activity on a sound economical basis.

Estimated cost

If built by launching the necessary materials from Earth, the cost for the system estimated by Birch in 1980s money was around $31 billion (for a "bootstrap" system intended to expand to 1000 times its initial size over the following year, which would otherwise cost 31 trillion dollars) if launched using Shuttle-derived hardware, whereas it could fall to $15 billion with space-based manufacturing, assuming a large orbital manufacturing facility is available to provide the initial 180,000 tonnes of steel, aluminium, and slag at a low cost, and even lower with orbital rings around the Moon. The system's cost per kilogram to place payloads in orbit would be around $0.05.[9]

Types of orbital rings

The simplest type would be a circular orbital ring in LEO.

Two other types were also defined by Paul Birch:

- Eccentric orbital ring systems – these are rings that are in the form of a closed shape with varying altitude

- Partial orbital ring systems[4] – this is essentially a launch loop

In addition, he proposed the concept of "supramundane worlds" such as supra-jovian and supra-stellar "planets". These are artificial planets that would be supported by a grid of orbital rings that would be positioned above a planet, supergiant or even a star.[10]

Orbital rings in fiction

Print

In the close of Arthur C. Clarke's Fountains of Paradise (1979), a reference is made to an orbital ring that is attached in the distant future to the space elevator that is the basis of the novel.

Arthur C. Clarke's 3001: The Final Odyssey (1997) features an orbital ring held aloft by four enormous inhabitable towers (assumed successors to space elevators) at the Equator.

The manga Battle Angel Alita (1990-1995) prominently features a slightly deteriorated orbital ring.

Orbital rings are used extensively in the collaborative fiction worldbuilding website Orion's Arm.[11]

The third part of Neal Stephenson's book Seveneves has an orbital ring around a moon-less earth.

Visual media and gaming

In the movie Starship Troopers, an orbital ring is shown encircling the Moon.

The second iteration of the anime series Tekkaman features a complete ring, though abandoned and in disrepair due to war, and without surface tethers.

The anime series Kiddy Grade also uses orbital rings as a launch and docking bay for spaceships. These rings are connected to large towers extending from the planets surface.

The anime Mobile Suit Gundam 00 also prominently features an orbital ring, which consists primarily of linked solar panels. The ring is connected to earth via three space elevators. This ring effectively provides near unlimited power to earth. Later in the series the ring also shows space stations mounted on its surface.

The opening battle of Star Wars: The Clone Wars's Season 6 pilot takes place on some form of ring-shaped orbital space station surrounding the planet of Ringo Vinda.

In the Warhammer 40,000 universe, Mars has a large orbital ring called the Ring of Iron. It is primarily used as a shipyard for interstellar craft. It is the largest man made structure in the galaxy. The planet Medusa also has such a ring, called Telstarax, hailing from the Dark Age of Technology, but it is largely plundered and wrecked.

The game X3 Terran Conflict features a free-floating orbital ring around the Earth, which is shattered by an explosion and subsequently de-orbited in X3: Albion Prelude

In the game Xenoblade Chronicles 2 there is a giant tree that has grown around the base of an Orbital Ring.

See also

- Megascale engineering

- Non-rocket spacelaunch

- Niven Ring (in the novel Ringworld): orbital ring around a star

- Space tether

References

- Nikola Tesla, My Inventions, part III: My Later Endeavors (The "gigantic machine" he refers to is the Hadley circulation of the Earth's weather system).

- Colin McInnes, "Nonlinear Dynamics of Ringworld Systems", J. British Interplanetary Soc., Vol. 56 (2003). (Accessed 6 April 2016)

- Carl A. Brannen, "Niven Ring Gravitational Stability" (Accessed 6 April 2016)

- Paul Birch, "Orbital Ring Systems and Jacob's Ladders - I", Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, Vol. 35, 1982, pp. 475–497. (see pdf) (Accessed 6 April 2016).

- Paul Birch, "Orbital Ring Systems and Jacob's Ladders - II", Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, Vol. 36, 1982, 115. (pdf).

- Paul Birch, "Orbital Ring Systems and Jacob's Ladders - III", Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, Vol. 36, 1982, 231. (pdf).

- Anatoly Yunitskiy, "в космос на колесе" ("To Space by Wheel"), Техника-молодежи ("Technical Youth"), No. 6, June 1982, ISSN 0320-331X, pp. 34–37 and back cover. (pdf (alternate source: pdf) (Accessed 25 July 2019).

- A. Meulenberg and P. S. Karthik Balaji, "The LEO Archipelago: A system of earth-rings for communications, mass-transport to space, solar power, and control of global warming", Acta Astronautica 68, 2011, 1931–1946.

- "Orbital Ring Systems and Jacob's Ladders - I-III".

- Paul Birch, "Supramundane Planets", Journal of the British interplanetary Society, Vol. 44, 1991, 169.

- Space Fountains and Orbital Rings, Orion's Arm.

External links

- Video: MegaStructures 01: Orbital Rings & Space Elevators

- Better more recent video: Orbital Rings

- Paul Birch Web Archive at Orion's Arm

- String Transport Systems: on Earth and in space (Anatoly Yunitskiy's book)

![]()