Norwich Castle

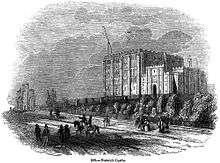

Norwich Castle is a medieval royal fortification in the city of Norwich, in the English county of Norfolk. It was founded in the aftermath of the Norman conquest of England when William the Conqueror (1066–1087) ordered its construction because he wished to have a fortified place in the town of Norwich. It proved to be one of his two castles in East Anglia, the other being Wisbech.[2] In 1894 the Norwich Museum moved to Norwich Castle and it has been a museum ever since. The museum & art gallery holds significant objects from the region, especially works of art, archaeological finds and natural history specimens.

| Norwich Castle | |

|---|---|

Norwich Castle, March 2009 | |

| Type | Motte-and-bailey castle |

| Location | Norwich |

| Coordinates | 52.6286°N 1.2964°E |

| Height | 27 metres (89 ft) |

| Built | 1067 onwards |

| Architectural style(s) | Norman |

| Governing body | Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 26 February 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1372724[1] |

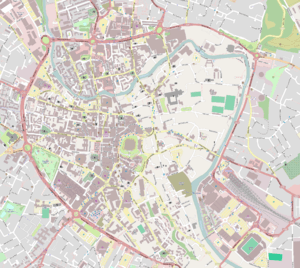

Location of Norwich Castle in Norwich  Norwich Castle (Norfolk) | |

The castle is one of the city's Norwich 12 heritage sites.

History

Norwich Castle was founded by William the Conqueror some time between 1066 and 1075. It originally took the form of a motte and bailey.[3] Early in 1067, William the Conqueror embarked on a campaign to subjugate East Anglia, and according to military historian R. Allen Brown it was probably around this time that the castle was founded.[4] It was first recorded in 1075, when Ralph de Gael, Earl of Norfolk, rebelled against William the Conqueror and Norwich was held by his men. A siege was undertaken, but ended when the garrison secured promises that they would not be harmed.[5]

Norwich is one of 48 castles mentioned in the Domesday Survey of 1086. Building a castle in a pre-existing settlement necessitated the destruction of existing properties. At Norwich, estimates vary that between 17 and 113 houses occupied the site of the castle.[6] Excavations in the late 1970s discovered that the castle bailey was built over a Saxon cemetery.[7] The historian Robert Liddiard remarks that "to glance at the urban landscape of Norwich, Durham or Lincoln is to be forcibly reminded of the impact of the Norman invasion".[8] Until the construction of Orford Castle in the mid-12th century under Henry II, Norwich was the only major royal castle in East Anglia.[9]

The stone keep, which still stands today, was probably built between 1095 and 1110.[3] In about the year 1100, the motte was made higher and the surrounding ditch deepened.[10] During the Revolt of 1173–1174, in which Henry II's sons rebelled against him and started a civil war, Norwich Castle was put in a state of readiness. Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk was one of the more powerful earls who joined the revolt against Henry.[11] With 318 Flemish soldiers that landed in England in May 1174, and 500 of his own men, Bigod advanced on Norwich Castle. They captured it and took fourteen prisoners who were held for ransom. When peace was restored later that year, Norwich was returned to royal control.[12]

The Normans introduced the Jews to Norwich and they lived close to the castle. A cult was founded in Norwich in the wake of the murder of a young boy, William of Norwich, for which the Jews of the city were blamed.[13] In Lent 1190, violence against Jews erupted in East Anglia and on 6 February (Shrove Tuesday) it spread to Norwich. Some fled to the safety of the castle, but those who did not were killed in their hundreds.[14] The Pipe Rolls, records of royal expenditure, note that repairs were carried out at the castle in 1156–1158 and 1204–1205.[15]

The castle was used as a prison for felons and debtors from 1220, with additional buildings constructed on the top of the motte next to the keep. The prison reformer John Howard visited it six times between 1774 and 1782.[16] These buildings were demolished and rebuilt between 1789 and 1793 by Sir John Soane, and more alterations were made in 1820. The use of the castle as a gaol ended in 1887, when it was bought by the city of Norwich to be used as a museum. The conversion was undertaken by Edward Boardman and the museum opened in 1895.[10]

The forebuilding attached to the keep was pulled down in 1825.[17] Although the keep remains, its outer shell has been repaired repeatedly, most recently in 1835–9 by Anthony Salvin, with James Watson as mason using Bath stone. None of the inner or outer bailey buildings survive, and the original Norman bridge over the inner ditch was replaced in about the year 1825.[10] During the renovation, the keep was completely refaced based faithfully on the original ornamentation.[18]

Present day

The castle remains a museum and art gallery today and still contains many of its first exhibits, as well as many more recent ones. Two galleries feature the museum's fine art collection, including costume, textiles, jewellery, glass, ceramics and silverware, and a large display of ceramic teapots. Other gallery themes include Anglo-Saxons (including the Harford Farm Brooch).[19]

The fine art galleries include works from the 17th to 20th centuries, and include English watercolour paintings, Dutch landscapes and modern British paintings. The castle also houses a good collection of the work of the Flemish artist Peter Tillemans.[20]

Norwich Castle is a Scheduled Ancient Monument and Grade I listed building.[3] Visitors can tour the castle keep and learn about the castle through interactive displays. Separate tours are also available of the dungeon and the battlements. Although not permanently on display, one of the largest collections it holds is the butterfly collection of Margaret Fountaine. An unusual artefact is the needlework done by Lorina Bulwer at the turn of the twentieth century whilst she was confined in a workhouse. The work has featured on the BBC.[21]

Architecture

G. T. Clark, a 19th-century antiquary and engineer, described Norwich's great tower as "the most highly ornamented keep in England".[22] It was faced with Caen stone over a flint core. The keep is some 95 ft (29 m) by 90 ft (27 m) and 70 ft (21 m) high, and is of the hall-keep type, entered at first floor level through an external structure called the Bigod Tower. The exterior is decorated with blank arcading. Castle Rising is the only other comparable keep in this respect.[10] Internally, the keep has been gutted so that nothing remains of its medieval layout. The uncertainty surrounding the keep's arrangement has led to scholarly debate. What is agreed on is that it had a complex domestic arrangement, with a kitchen, chapel, a two-storey high hall, and 16 latrines.[23]

Exhibit highlights

The Paston Treasure is a painting commissioned around 1663 either by Sir William Paston (1610-1663), or by his son Robert (1631-1683). The identity of the artist is unknown, however it is likely that it was a Dutch artist working in a studio at the principal residence of the Pastons at Oxnead.[24] The artwork can be placed within the mid-seventeenth century Dutch still life tradition, with elements that conform to the genre of vanitas. Still life paintings usually feature one or two objects which are artists' stock items, included only for their symbolism. On the other hand, the majority of the objects represented in The Paston Treasure were all real, as they correspond to an existing item in the inventories of the Pastons'. Therefore, not only it was commissioned as a memento mori, but also as a record for the family's wealth and own collections. It was also meant to be commemorative of the death of a family member, probably William Paston.[25]

The painting debuted in America with an exhibition held at the Yale Center For British Art. Now it is currently in display at the Castle, in The Paston Treasure Riches & Rarities of the Known World exhibition curated by Francesca Vanke, which reunites for the first time in 350 years the painting with some of the objects depicted.[26]

The Happisburgh hand axe is made of flint, and measures 12.2 cm x 7.8 cm.[27] The discovery of this Lower Palaeolithic hand axe in 2000 along the Norfolk coast at Happisburgh transformed our understanding of early human occupation in Britain.[28] Dated and shown to be from 550,000 to 700,000 years old, it is now the oldest human-made object in North Europe, doubling the known duration of human occupation in Britain.[27] Analysis of pollen in the silt allowed the archaeologists to build a picture of temperate woodland with the existence of pine, alder, oak, elm and hornbeam trees in evidence at the time the handaxe was made.[28]

The Cavalry Parade Helmet and Visor was found in the River Wensum at Worthing in 1947 and 1950 respectively. The items, of Roman origin, date to the first half of the third century CE.[29] They are an important testimony of the presence of Roman army personnel in central Norfolk during the later period of the Roman occupation.[29] The helmet is made from a single sheet of gilded bronze, highly decorated as to represent a feathered eagle's head on the crest, foliate-tailed beasts on either side and a plain triangular front panel with feather borders on either side at the top, with the lower ends terminating in birds' heads.[30] The visor mask complements the helmet by carrying similar repoussé decoration, depicting Mars on one side and Victory on the other.[29] These two objects are not a fitting pair, although they can be considered together as each would have originally had been coupled with a similar complementary object.[29]

The unique Anglo-Saxon ceramic figurine now known as Spong Man was found in 1979 in Spong Hill.[31] The figure is shown sat on a chair decorated with incised panelling and is leaning forwards with head in hands wearing a round flat hat. It is likely to have once sat on the lid of a pagan funerary urn and is a unique object in North Western Europe.[31] Although it is labelled as a man, its gender is unclear, as there are no distinctive anatomic details.[31] Exactly why this figurine was created is still a mystery. It is the earliest Anglo-Saxon three-dimensional figure ever found. It may be a representation of a deity whose identity is now lost, but it is still a great artifact that reminds us how little we know about religion in this early migration period across northern Europe.[32]

Also known as neck-rings, torcs were a characteristic kind of jewel used in the Iron Age across Europe.[33] They would have been worn by prominent people within society as a symbol of status and power.[34] The rare tubular gold torc known as the Gold Tubular Torc came from the Snettisham Treasure. It was found in 1948 at Snettisham, alongside a large number of other torcs, carefully disposed in the ground, confirming that burial rituals had great significance within the people of Late Iron Age Norfolk.[34]

Also known as The Seven Sorrows of Mary, the Ashwellthorpe Triptych has significant connections with South Norfolk and its long trading tradition with Holland.[35] This Flemish altarpiece was commissioned by the Norfolk family of the Knyvettes of Ashwellthorpe.[35] Christopher Knyvettes was sent by King Henry VIII to the Netherlands in 1512, when he commissioned this painting to Master of the Legend of the Magdalen.[36] Both Christopher and his wife Catherina are represented kneeling to Mary, mother of Jesus in the foreground of the composition, showing their religious devotion and wealth.[35]

Dragons in England are famous through the legend of Saint George, however, they have always been particular important in Norwich since the medieval period.[37] The Norwich Snapdragon was made to reflect the civil power and wealth of the city within Norfolk and was used during a procession which combined the celebration of the city's saint and the installation of the new major of the town.[38] The Snapdragon at the Norwich Castle, known as Snap, is the last complete example of the civic snapdragon. Like all others, it was built to contain one person, its body is made of basketwork, painted with gold and red scales over a green body and red underside, while the person's legs were hidden within a canvas 'skirt'.[38]

Norwich River: Afternoon by the Norwich School of Painters artist John Crome. The Norwich Society of Artists was founded in 1803 by Crome and Robert Ladbrooke and brought together professional painters and drawing masters such as John Sell Cotman, James Stark, George Vincent as well as other talented amateur artists,[39] who were often inspired by the East Anglian landscape, and were influenced by Dutch landscape painters.[39] This oil on canvas is considered one of the finest works made by Crome. It depicts the River Wensum, near New Mills, at St Martin's Oak, close to where the artist lived, in Norwich.[39]

The Norfolk Regiment First World War Casualty Book is a unique graphic record of the Norfolk Regiment's participation in the First World War. It records details of more than 15,000 soldiers from the regular and service battalions in 1914 to their return home in 1919.[40] Each entry of the book contains the soldier's name, service number, battalion and details of their health. It also records those who perished in action.[41]

Part of a quartet of rare examples of English medieval art, the stained-glass roundel depicting December is an example of the Norwich School of stained-glass.[42] It shows clear Flemish influences, and it is possible that it has been made by one of the Norwich Strangers, immigrants of the sixteenth century from the Low Countries.[42] It is thought to have been made for the Major Thomas Pykerell's house.[42] originally there would have been twelve roundels depicting the Labours of The Months, a popular pageant in Norwich during that period.[42] This roundel in particular depicts the King of Christmas.[42] Of the original twelve only four now survive, depicting December, September, probably March and either April or November.[42]

References

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1372724)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- George Anniss (1977). A history of Wisbech Castle. EARO. ISBN 0-904463-15-X.

- Historic England, "Norwich Castle (132268)", PastScape, retrieved 29 December 2010

- Allen Brown 1976, p. 31

- Cathcart King 1983, pp. 308, 312

- Harfield 1991, pp. 373, 384

- Webster & Cherry 1980, pp. 228–229

- Liddiard 2005, p. 36

- Campbell 2004, p. 164

- Pevsner 1997, pp. 256–260

- Warren 1973, p. 135

- Wareham 1994, p. 241

- Rawcliffe & Wilson 2006, p. 42

- Skinner 2003, p. 30

- Renn 1968, p. 262

- Howard, John (1 January 1784). "The State Of The Prisons In England And Wales: With Preliminary Observations, And An Account Of Some Foreign Prisons And Hospitals". Cadell – via Google Books.

- Renn 1968, p. 259

- Renn 1968, p. 259, plate XXXII

- "Anglo Saxons and Vikings at Norwich Castle Gallery". A Sense Of Place. BBC. 21 May 2004. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- Norfolk Museums Archaeology Service (Norwich Castle Museum Art Gallery): Peter Tillemans, Art UK, 2011, retrieved 6 September 2011

- BBC Documentary 2015 - Antiques Roadshow Detectives 2 Lorina Bulwer, BBC, retrieved 11 April 2015

- Clark 1881, p. 268

- Goodall 2011, p. 112

- Vanke 2018, p. 8

- Vanke 2018, pp. 8–9

- "The Paston Treasure: a microcosm of the known world". Yale University. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Davis & Pestell 2015, p. 25

- "Object: Handaxe (axe)". norfolkmuseumscollections.org.

- Davis & Pestell 2015, p. 51

- "Object: Sports helmet (helmet)". norfolkmuseumscollections.org.

- "Object: Funerary urn (collection)". norfolkmuseumscollections.org.

- Davis & Pestell 2015, p. 62

- Davis & Pestell 2015, p. 37

- Davis & Pestell 2015, p. 38

- Davis & Pestell 2015, p. 98

- "Object: Ashwellthorpe Triptych (painting)". norfolkmuseumscollections.org. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Davis & Pestell 2015, p. 113

- Davis & Pestell 2015, p. 114

- Davis & Pestell 2015, p. 122

- Davis & Pestell 2015, p. 142

- Davis & Pestell 2015, p. 143

- "Object: Roundel". norfolkmuseumscollections.org.

Bibliography

- Allen Brown, Reginald (1976) [1954], Allen Brown's English Castles, Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, ISBN 1-84383-069-8

- Campbell, J. (2004), "The Building of Orford Castle: A Translation from the Pipe Rolls, 1163–78" (PDF), English Historical Review, 119

- Cathcart King, David James (1983), Castellarium Anglicanum: An Index and Bibliography of the Castles in England, Wales and the Islands. Volume II: Norfolk–Yorkshire and the Islands, London: Kraus International Publications, ISBN 0-527-50110-7

- Clark, George Thomas (1881), "The castles of England and Wales at the Latter part of the Twelfth Century", The Archaeological Journal, 38: 258–276, 335–351, doi:10.1080/00665983.1881.10851987

- Davis, John A.; Pestell, Tim (2015), A History of Norfolk in 100 Objects, The History Press

- Goodall, John (2011), The English Castle 1066–1650, London: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11058-6

- Harfield, C. G. (1991), "A Hand-list of Castles Recorded in the Domesday Book", English Historical Review, 106: 371–392, doi:10.1093/ehr/CVI.CCCCXIX.371, JSTOR 573107

- Liddiard, Robert (2005), Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500, Macclesfield: Windgather Press Ltd, ISBN 0-9545575-2-2

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Wilson, Bill (1997). Norfolk 1: Norwich and North East. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300096071.

- Rawcliffe, Carole; Wilson, Richard (2006), Medieval Norwich, Continuum, ISBN 978-1-85285-546-8

- Renn, Derek F. (1968), Norman Castles in Britain, John Baker Publishers

- Skinner, Patricia (2003), The Jews in Medieval Britain: Historical, Literary, and Archaeological Perspectives, Boydell Press, ISBN 978-0-85115-931-7

- Wareham, Andrew (1994), "The Motives and Politics of the Bigod Family, c.1066–1177", Anglo-Norman Studies, The Boydell Press, XVII, ISSN 0954-9927

- Warren, W. L. (1973), Henry II, Eyre Methuen, ISBN 978-0-520-02282-9

- Webster, Leslie; Cherry, John (1980), "Medieval Britain in 1979" (PDF), Medieval Archaeology, 24: 218–264, doi:10.1080/00766097.1980.11735426

- Vanke, Francesca. (2018), The Paston Treasure Riches & Rarities of the Known World, Norfolk Museum Service

Further reading

- Heslop, T. A. (1994), Norwich Castle Keep: Romanesque Architecture and Social Context, Norwich: Centre for East Anglian Studies, ISBN 978-0-906219-38-6

- Shepherd Popescu, Elizabeth (1997), Guy De Boe; Frans Verhaeghe (eds.), "Recent Excavations at Norwich Castle", Military Studies in Medieval Europe – Papers of the 'Medieval Europe Brugge 1997' Conference, 11: 187–191, archived from the original on 17 December 2011

- Shepherd, Elizabeth (2000), "Norwich Castle", Current Archaeology, 170: 52–59

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Norwich Castle. |