Nigerian Chieftaincy

The Nigerian Chieftaincy is the chieftaincy system that is native to Nigeria. Consisting of everything from the country's monarchs to its titled family elders, the chieftaincy as a whole is one of the oldest continuously existing institutions in Nigeria and is legally recognized by its government.

History

Nigerian pre-colonial states tended to be organized as city-states. The empires that did exist, like the Kanem-Borno empire, the Oyo empire, the Benin empire and the Sokoto caliphate, were essentially coalitions of these individual city-states. Due to this, a great deal of local power was concentrated in the hands of rulers that remained almost permanently in their capitals. These rulers had sacred functions—a number of them were even considered to be sacred themselves—and therefore often lived in seclusion as a result.[1] Their nobles, both hereditary and otherwise, typically also had functions that were tied to the religious traditions of the kingdoms that they served.

In the South, the nobles ruled the states on a day to day basis on behalf of their monarchs by way of a series of initiatory secret societies. These bodies combined the aforementioned priestly functions with judicial ones, and also traditionally provided advisers to the monarchs in question.[2] Some of these societies, like Ogboni and Nze na Ozo, have survived to the present day as aristocratic social clubs within their respective tribes.[3] Meanwhile, in the North, the emirates of the old caliphate were usually divided into districts, and these districts were in turn ruled by nobles known as Hakimi (pl. Hakimai) that were subject to the monarchs.

As a general rule, titles didn't always go from father to son. Regardless of this many royal and noble families provided a number of titleholders over several generations.[4] In the South, the titles held by nobles were often not the same ones as those that had been held by others in their lineages. Some chiefs had even been untitled slaves, and therefore had had no titled forebears, prior to their eventual ascension to the ranks of the aristocracy.

Although dominated by the titled men mentioned above, several kingdoms also had parallel traditions of exclusively female title societies that operated in partnership with their male counterparts. Others would reserve specially created titles, such as the Yoruba Iyalode, for their womenfolk.[5]

In the early colonial period, Nigerian chiefs—both monarchs and nobles—came to be divided into two opposing camps: the freedom fighters on the one end and the collaborators on the other. The former used a variety of tactics to work against the ascendancy of the British in Nigeria. As a result, the colonists responded by using both direct methods (such as armed incursions) and indirect ones (such as supporting rival claimants to the Nigerian titles in an attempt to frustrate the freedom fighters) to counteract their efforts. For their part the latter became immensely wealthy due to trade with Britain, and often had their titles confirmed, restored or created by her as a result. After the colonists consolidated their control of the country following the Berlin conference, they made it a policy to banish, imprison or kill any chief that was too independently minded. Through indirect rule, Native Authorities were subsequently propped up and rewarded for loyalty to the new regime.[6] Unsurprisingly, popular uprisings were rare after 1900.

Following Nigeria's independence in 1960, each federated unit of the country had a House of Chiefs that was part of its lawmaking system. They have since been replaced by the largely ceremonial Councils of Traditional Rulers. In addition, many of the founding fathers and mothers of the First Republic—including the leading troika of Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, Chief Obafemi Awolowo and Alhaji Sir Ahmadu Bello—were all royals or nobles in the Nigerian chieftaincy system.[7][8] This has continued to operate since their time as a locally controlled honours system alongside its nationally controlled counterpart, which is itself within the gift of the Federal Government.[9][10]

Today

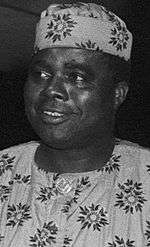

Today, many prominent Nigerians aspire to the holding of a title. Both Chief Olusegun Obasanjo and Alhaji Umaru Musa Yar'Adua, one time presidents of Nigeria, have belonged to the noble stratum of the Nigerian chieftaincy.[11] Nigerian traditional rulers and their titled subordinates currently derive their powers from various Chiefs' Laws that are official parts of the body of contemporary Nigerian laws.[12] As a result, the highly ranked amongst them typically receive staffs of office—and by way of them official recognition—from the governors of the states of the Federation as the culminations of their coronation and investiture rites. Thus installed, they then have the power to install inferior chiefs themselves.

Chieftaincy titles are often of differing grades, and are usually ranked according to a variety of diverse factors. Whether or not they are recognized by the government, whether they are traditionally powerful or purely honorary, what the relative positions of the title societies that they belong to (if any) are in the royal orders of precedence, their relative antiquity, how expensive they are to acquire, whether or not they are hereditary, and a number of other such customary determinants are commonly used to ascribe hierarchical positions. A number of kingdoms also make use of colour-coded regalia to denote either allegiance to particular title societies or individual rank within them. Examples of this phenomenon include the Red-Capped Chiefs of Igboland and the White-Capped Chiefs of Lagos, each the highest ranked group of noble chiefs in its respective sub-system.

Nigerian titleholders

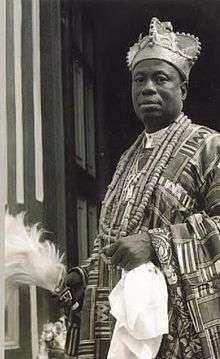

Monarchs

Colonial

Post-colonial

- Nigerian traditional rulers

- Lamido

- Sultan of Sokoto

- Emir of Kano

- Shehu of Borno

- Oba

- Ooni of Ife

- Alaafin of Oyo

- Oba of Benin

- Eze

- Eze Nri

- Obi of Onitsha

- Igwe of Nnewi

- Lamido

See also

- Nigerian heraldry

- Nigerian traditional rulers

- Nigerian traditional states

References

- "In Pictures: Country of Kings, Nigeria's many monarchs". BBC news. 13 October 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Ejiogu 2004.

- Ndeche, Chidirim (16 September 2018). "The Most Prominent Secret Societies In Nigeria". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Johnson 1921.

- Uchendu, Egodi (22 January 2006). "Gender and Female Chieftaincy in Anioma". Asian Women. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Egbe, Enyi John (1 January 2014). "Native Authorities and Local Government Reforms in Nigeria Since 1914". Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Sklar 2004.

- Obadare and Adebanwi 2011, p. 32.

- "Jeje Oladele and others versus Oba Adekunle Aromolaran II and others". The Supreme Court of Nigeria. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- "Traditional States of Nigeria". worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Ewokor, Chris (1 August 2007). "Nigerians go crazy for a title". BBC news. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Abolarin, Oba Adedokun (3 April 2017). "Traditional Institutions and Traditional Rulers in National Development". The Palace of Oke-Ila. Retrieved 17 October 2019.