Native Indonesians

Native Indonesians, also Pribumi (literally "first on the soil"), is a term used to distinguish Indonesians whose ancestral roots lie mainly in the archipelago from Indonesians of known (partial) foreign descent, like Chinese Indonesians and Indo-Europeans (Eurasians).

.jpg) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 210 million (Worldwide; 2006 estimate)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,085,658[2] | |

| 850,000[3] | |

| 500,000 | |

| 102,100[4] | |

| 101,270[5][6] | |

| 86,196[7] | |

| 75,000[8] | |

| 10,000[9] | |

| Languages | |

| Indonesian languages (Indonesian, Malay, Javanese, Sundanese, Batak, Madurese, etc.) | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (predominantly Sunnis, Shias and others),[10] Christianity (Protestantism, Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy), Hindu Dharma, Buddhism, Animism, Shamanism, Sunda Wiwitan, Kaharingan, Parmalim, Kejawen, Naurus, Aluk' To Dolo, etc. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indonesians | |

a The figure in Malaysia merely asserts those who hold an Indonesian citizenship, the figure does not include Malaysians who have some Indonesian ancestry which potentially is double or triple of figure, due to constant migrations for millennia. | |

Etymology and historical context

The term pribumi was popularized after Indonesian independence as a respectful replacement for the Dutch colonial term inlander (normally translated as "native" and seen as derogatory).[11] It derives from Sanskrit terms pri (before) and bhumi (earth). Before independence the term bumiputra (Malay: son of the soil) was more commonly used as an equivalent term to pribumi.

Following independence, the term was normally used to distinguish indigenous Indonesians from citizens of foreign descent (especially Chinese Indonesians). Common usage distinguished between pri and non-pri.[12] Although the term is sometimes translated as "indigenous", it has a broader meaning than that associated with Indigenous peoples.

The term WNI keturunan asing (WNI = "Indonesian citizen", keturunan asing = foreign descent), sometimes just WNI keturunan or even WNI, has also been used to designate non-pri Indonesians.[13]

In practice, usage of the term is fluid. Pri is seldom used to refer to Indonesians of Melanesian descent, although it does not exclude them. Indonesians of Arab descent sometimes refer to themselves as pri. Indonesians with some exogenous ancestry who show no obvious signs of identification with that ancestry (such as former President Abdurrahman Wahid who is said to have had Chinese ancestry) are seldom called non-pri. The term bumiputra is sometimes used in Indonesia with the same meaning as pribumi, but is more commonly used in Malaysia, where it has a slightly different meaning.[14]

The term putra daerah ("son of the region") refers to a person who is indigenous to a specific locality or region.

In 1998, the Indonesian government of President B.J. Habibie instructed that neither pri nor non-pri should be used, on the grounds that they promoted ethnic discrimination.[15][16]

The Dutch East India Company, which dominated parts of the archipelago from the 17th century, classified its subjects mainly by religion, rather than ethnicity. The colonial administration which took power in 1815 shifted to a system of ethnic classification. Initially they distinguished between Europeans (Europeanen) and those equated with them (including native Christians) and Inlanders and those equated with them (including non-Christian Asians).

Over time, native were gradually shifted de facto into the Inlander category, while Chinese Indonesians, Arab Indonesians and others of non-Indonesian descent were gradually given separate status as Vreemde Oosterlingen ("Foreign Orientals"). The system was patriarchal, rather than formally racial. A child inherited his/her father's ethnicity if the parents were married; the mother's ethnicity if they were unmarried. The off-spring of a marriage between a European man and an Indonesian woman were legally European.

Today, Indonesian dictionary defines pribumi as penghuni asli which translates into "original, native or indigenous inhabitant".[17]

Background

Pribumi make up about 95% of the Indonesian population.[1] Using Indonesia’s population estimate in 2006, this translates to about 230 million people. As an umbrella of similar cultural heritage among various ethnic groups in Indonesia, Pribumi culture plays a significant role in shaping the country’s socioeconomic circumstance.

The United States Library of Congress Country Study of Indonesia defines Pribumi as:

Literally, an indigene, or native. In the colonial era, the great majority of the population of the archipelago came to regard themselves as indigenous, in contrast to the non-indigenous Dutch and Chinese (and, to a degree, Arab) communities. After independence the distinction persisted, expressed as a dichotomy between elements that were pribumi and those that were not. The distinction has had significant implications for economic development policy

— Indonesia: A Country Study, Glossary[18]

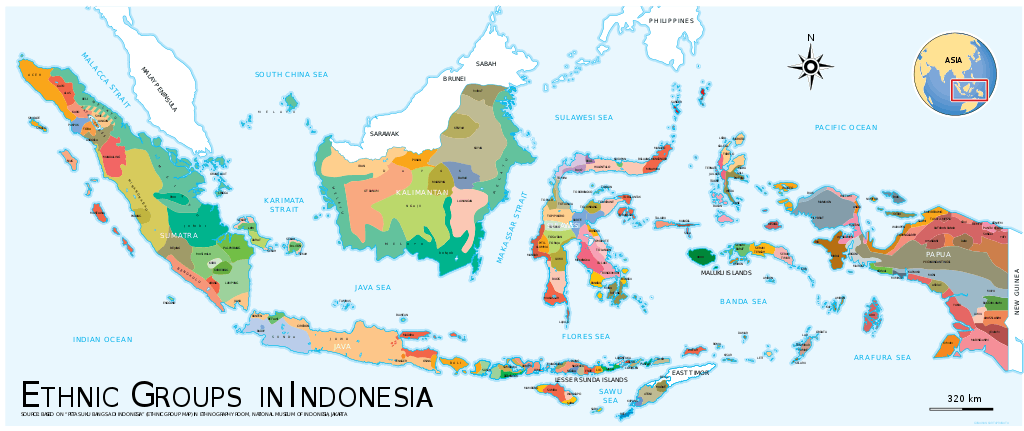

There are over 300 ethnic groups in Indonesia,[19] of which 200 are of Native Indonesian ancestry.

The largest ethnic group in Indonesia are the Javanese people who make up 41% of the total population. The Javanese are concentrated on the island of Java but millions have migrated to other islands throughout the archipelago.[20] The Sundanese, Malay, and Madurese are the next largest groups in the country.[20] Many ethnic groups, particularly in Kalimantan and the province of Papua, have only hundreds of members. Most of the local languages belong to the Austronesian language family, although a significant number, particularly in North Maluku and West Papua, speak Papuan languages.

The division and classification of ethnic groups in Indonesia is not rigid and in some cases are unclear as the result of migrations, along with cultural and linguistic influences; for example some may agree that the Bantenese and Cirebonese belong to different ethnic groups with their own distinct dialect, however others might consider them to be Javanese sub-ethnicities, as members of the larger Javanese people. The same considerations may apply to the Baduy people who share so many similarities with the Sundanese people that they can be considered as belonging to the same ethnic group. The clearest example of hybrid ethnicity are the Betawi people, the result of a mixture of different native ethnicities that have merged with people of Arab, Chinese and Indian origins since the era of colonial Batavia (Jakarta).

The proportional populations of Native Indonesians according to the (2009 census) is as follows:

| Ethnic groups | Population (million) | Percentage | Main Regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Javanese | 95.217[21] | 40.2[21] | Central Java, Yogyakarta, East Java, Lampung, Jakarta[21] |

| Sundanese | 31.765 | 15.4 | West Java, Banten, Lampung |

| Malay | 8.789 | 4.1 | Sumatra eastern coast, West Kalimantan |

| Madurese | 6.807 | 3.3 | Madura island, East Java |

| Batak | 6.188 | 3.0 | North Sumatra |

| Bugis | 6.000 | 2.9 | South Sulawesi, East Kalimantan |

| Minangkabau | 5.569 | 2.7 | West Sumatra, Riau |

| Betawi | 5.157 | 2.5 | Jakarta, Banten, West Java |

| Banjarese | 4.800 | 2.3 | South Kalimantan, East Kalimantan |

| Bantenese | 4.331 | 2.1 | Banten, West Java |

| Acehnese | 4.000 | 1.9 | Aceh |

| Balinese | 3.094 | 1.5 | Bali |

| Dayak | 3.009 | 1.5 | North Kalimantan, West Kalimantan, Central Kalimantan |

| Sasak | 3.000 | 1.4 | West Nusa Tenggara |

| Makassarese | 2.063 | 1.0 | South Sulawesi |

| Cirebonese | 1.856 | 0.9 | West Java, Central Java |

Physical characteristics

The skin color of native Indonesians ranges from fair skin with yellowish undertone to light brown to very dark brown or black skin color. Archaeologist Peter Bellwood claims that the "vast majority" of people in Indonesia and Malaysia, the region he calls the "clinal East Eurasian-Australo-Melanesian zone", are "Southern East Eurasians" but have a "high degree" of Australo-Melanesian admixture in the eastern portion of Indonesia.[22]

Sawo matang (lit. "ripe sapodilla") usually refers to the skin colour of the Pribumis in Indonesia which connotes "mid light to dark tone brown" especially for those who live in Java, Bali, Sumatra, etc. For other places like in Borneo, Sulawesi, and eastern parts of Indonesia, native people tend to have darker skin colour who actually come from the east of Indonesia and for those who live in high altitude areas and highlands tend to have lighter skin colour like people from Sundanese, Manado, Tomohon, Dayak, etc. For islandic people, they tend to have dark skin colour with all of the physical characteristics depending on the geographical areas they inhabit.

Genetic research

Most Native Indonesians are genetically close to Asians while the more east one goes the more the people show Melanesian affinity. Geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza claims that there is a genetic division between East and Southeast Asians.[23] In a similar manner, Zhou Jixu agrees that there is a physical difference between these two populations.[24] Other geneticists have found evidence for four separate populations, carrying distinct sets of non-recombining Y chromosome lineages, within the traditional Mongoloid category: North Asians, Han Chinese, Japanese and Southeast Asians.[25] The complexity of genetic data has led to doubt about the usefulness of the concept of a Mongoloid race itself, since distinctive East Asian features may represent separate lineages and arise from environmental adaptations or retention of common proto-Eurasian ancestral characteristics.[26]

Smaller groups

The regions of Indonesia have some of their indigenous ethnic groups. Due to migration within Indonesia (as part of government transmigration programs or otherwise), there are significant populations of ethnic groups who reside outside of their traditional regions.

- Java: Javanese, Sundanese, Bantenese, Betawi, Tengger, Osing, Badui

- Madura: Madurese

- Sumatra: Malays, Batak, Minangkabau, Acehnese, Lampung, Kubu

- Kalimantan: Malays, Dayak, Banjar

- Sulawesi: Makassarese, Buginese, Mandar, Minahasa, Buton, Gorontalo, Toraja, Bajau, Mongondow, Buroko, Bolango

- Lesser Sunda Islands: Balinese, Sasak

- The Moluccas: Nuaulu, Manusela, Wemale

- Papua: Dani, Bauzi, Asmat

See also

- Ethnic groups in Indonesia

- Culture of Indonesia

- Indonesians

- Overseas Indonesians

- List of Indonesian people

- National costume of Indonesia

- List of indigenous peoples

Non-Pribumi Indonesians:

- African Indonesians

- Arab Indonesians

- Chinese Indonesians

- Filipino Indonesians

- Indian Indonesians

- Indo people (mixed European-Indonesians)

- Jewish Indonesians

- Pakistani Indonesians

- Totok (Dutch Indonesians)

Notes

- "Pribumi". Encyclopedia of Modern Asia. Macmillan Reference USA. Archived from the original on July 11, 2007. Retrieved October 5, 2006.

- 2008. "Foreign Workers by Country of Origin (1999 -2008) - Official Portal of Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister's Department Malaysia" (PDF). Economic Planning Unit. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 16, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2012.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Migrant Communities in Saudi Arabia", Bad Dreams: Exploitation and Abuse of Migrant Workers in Saudi Arabia, Human Rights Watch, 2004

- Media Indonesia Online 2006-11-30

- "Race Reporting for the Asian Population by Selected Categories: 2010", 2010 Census Summary File 1, U.S. Census Bureau, archived from the original on October 12, 2016, retrieved February 21, 2012

- Barnes & Bennett 2002, p. 9

- Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of. "Browse Statistics". www.abs.gov.au.

- Reporter, Binsal Abdul Kader, Staff (August 17, 2009). "Expatriates celebrate 64th Indonesian Independence Day in Abu Dhabi". gulfnews.com.

- http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001530/153053e.pdf

- "Sunni and Shia Muslims". pewforum.org. January 27, 2011.

- William H. Frederick and Robert L. Worden, Indonesia: A Country Study (Washington: Library of Congress, 6th ed., 2011), p. 409.

- Kwik Kian Gie, in Leo Suryadinata, Political Thinking of the Indonesian Chinese, 1900-1995: A Sourcebook (Singapore University Press, 2nd ed., 1977), p.135.

- James T. Siegel, "Early Thoughts on the Violence of May 13 and 14, 1998 in Jakarta", Indonesia 66 (Oct. 1998), p. 90 (pp. 74–108).

- Sharon Siddique and Leo Suryadinata, "Bumiputra and Pribumi: Economic Nationalism (Indiginism) in Malaysia and Indonesia", Pacific Affairs, Vol. 54, No. 4 (Winter 1981–1982), pp. 662–687.

- Purdey, Jemma (2006). Anti-Chinese Violence in Indonesia, 1996–1999. Singapore: Singapore University Press. p. 179. ISBN 9971-69-332-1.

- Hasanah, Sovia (October 17, 2017). "Dasar Hukum yang Melarang Penggunaan Istilah "Pribumi"" [Law that based ban of "Pribumi" term]. hukumonline.com. hukumonline.com. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- "Pribumi". KBBI (in Indonesian).

- The Library of Congress, Federal Research Division. "Glossary—Indonesia". A Country Study: Indonesia. Retrieved October 4, 2006.

- Kuoni (1999). Far East, A world of difference. USA: Kuoni Travel & JPM Publications. p. 88.

- Indonesia's Population: Ethnicity and Religion in a Changing Political Landscape. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 2003.

- "Sebaran Suku Jawa Di Indonesia". www.kangatepafia.com. May 18, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- Bellwood, Peter. Pre-History of the Indo-malaysian Archipelago. Australian National University:1985. ISBN 978-1-921313-11-0

- Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca (September 29, 1998). "The Chinese human genome diversity project". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (20): 11501–3. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.20.11501. PMC 33897. PMID 9751692.

- http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp175_chinese_civilization_agriculture.pdf The Rise of Agricultural Civilization in China, Sino-Platonic Papers 175, Zhou Jixu, citing Ho Ping-ti, ISBN 0-226-34524-6

- Tajima, Atsushi; Pan, I-Hung; Fucharoen, Goonnapa; Fucharoen, Supan; Matsuo, Masafumi; Tokunaga, Katsushi; Juji, Takeo; Hayami, Masanori; Omoto, Keiichi; Horai, Satoshi (November 28, 2001). "Three major lineages of Asian Y chromosomes: implications for the peopling of east and southeast Asia". Human Genetics. 110 (1): 80–88. doi:10.1007/s00439-001-0651-9. PMID 11810301.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Mongoloid

Further reading

- Center for Information and Development Studies (1998). Pribumi dan Non-Pribumi dalam Perspektif Pemerataan Ekonomi dan Integrasi Sosial [Pribumi and Non-Pribumi in the Perspective of Economic Redistribution and Social Integration]. Jakarta, Indonesia: Center for Information and Development Studies.

- Suryadinata, Leo (1992). Pribumi Indonesians, the Chinese Minority, and China. Singapore: Heinemann Asia.