Naqa

Naqa or Naga'a (Arabic: ٱلـنَّـقْـعَـة, romanized: An-Naqʿah) is a ruined ancient city of the Kushitic Kingdom of Meroë in modern-day Sudan. The ancient city lies about 170 km (110 mi) north-east of Khartoum, and about 50 km (31 mi) east of the Nile River located at approximately MGRS 36QWC290629877. Here smaller wadis meet the Wadi Awateib coming from the center of the Butana plateau region,[1] and further north at Wad ban Naqa from where it joins the Nile. Naqa was only a camel or donkey's journey from the Nile, and could serve as a trading station on the way to the east; thus it had strategic importance.

The Roman Kiosk and the Temple of Apedemak | |

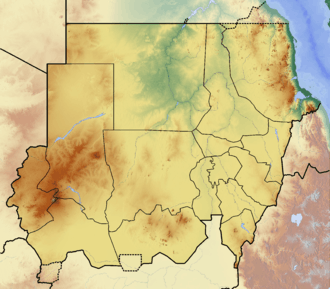

Shown within Northeast Africa  Naqa (Sudan) | |

| Alternative name | Naqa |

|---|---|

| Location | Naqa, Northern State, Sudan |

| Region | Nubia |

| Coordinates | 16°16′10″N 33°16′30″E |

| Type | Sanctuary |

| Official name | Archaeological sites of the Island of Meroe |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 2011 (35th session) |

| Reference no. | 1336 |

| Region | Arab States |

Naqa is one of the largest ruined sites in the country and indicates an important ancient city once stood in the location. It was one of the centers of the Kingdom of Meroë, which served as a bridge between the Mediterranean world and Africa. The site has two notable temples, one devoted to Amun and the other to Apedemak which also has a Roman kiosk nearby. With Meroë and Musawwarat es-Sufra it is known as the Island of Meroe, and was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011.[2]

Research

The first European travellers reached Naqa in 1822, before Hermann von Pückler-Muskau did in 1837. In 1843, it was visited by Richard Lepsius and his Prussian Egypt-Sudan expedition. He copied some of the inscriptions and representations of the temple standing here. In 1958 a team from Berlin's Humboldt University visited Naqa and documented the temple and restored part of the site along with the nearby site of Musawwarat es-Sufra in the 1960s.[3]

Since 1995, Naqa has been excavated by a German-Polish team with the participation of the Egyptian Museum of Berlin and the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. It is directed by Professor Dietrich Wildung and is financed by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) and also includes Polish archaeologist Professor Lech Krzyżaniak, and a small group of Polish archaeologists from Poznań.[1]

Structure

Naqa comprises several Meroitic temples dating to 4th century BC to 4th century AD, and the ruins of an apparent urban agglomeration and several burial grounds. Archaeologists cited Naqa as one of the most important centres of this first civilization of Black Africa.[1] The remains of various temples were found, but the two largest and most significant temples of Naqa are the Amun and Apedemak temples, also known as the Temple of the Lion. Both are still well preserve.[4]

Temple of Amun

Amun was a deity in Egyptian mythology who in the form of Amun-Ra became the focus of the most complex system of theology in Ancient Egypt. Whilst remaining hypostatic deities, Amun represented the essential and hidden, whilst in Ra he represented revealed divinity. As the creator deity "par excellence", he was the champion of the poor and central to personal piety. Amun was self-created, without mother and father, and during the New Kingdom he became the greatest expression of transcendental deity in Egyptian theology. His position as King of gods developed to the point of virtual monotheism where other gods became manifestations of him. With Osiris, Amun-Ra is the most widely recorded of the Egyptian gods.[5]

The Amun temple of Naqa was founded by King Natakamani and is 100 metres in length and has several statues of the ruler.[1] The temple is aligned on an east-west axis and is made of sandstone, which has been somewhat eroded by the wind. The temple is designed in the Egyptian style, with an outer court and colonnade of rams similar to the Temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal and Karnak, and leads to a hypostyle hall containing the inner sanctuary (naos).[3] The main entrances and walls of the temple contain relief carvings.

.jpg)

In 1999 the German-Polish archaeology team explored the area of the inner sanctuary of the temple where the main statue of the god was originally kept. They discovered an undamaged painted "altar", which includes iconography and names written in hieroglyphs of the king Natakamani and his wife Amanitore, founders of the temple. The altar is considered unique for Sudan and Egypt in that time period. A fifth statue of the king Natakamani was also discovered in this chamber along with a commemorative stone stela of Queen Amanishakheto who is believed to have been ruling the Meroites prior to the reign of Natakamani and Amanitore. The obverse shows a delicate sunken relief of the queen and a goddess who was a partner of the Meroitic lion god Apademak. The reverse and sides of the stela contain undeciphered Meroitic hieroglyphs and is considered by the discovery team to be one of the best examples of Meroitic art found to date.[1] After excavation, reconstruction and measurement of the temple of Amun for over a decade, on 1 December 2006, the Sudanese authorities regained management, giving responsibility to the Ministry of Culture.[6]

Another Amun temple named Naqa 200 and located on the slope of the nearby Gebel Naqa, the mountain overlooking the settlement of Naqa, has been excavated since 2004. It was built by Amanikhareqerem and is similar to the Temple of Natakamani and is dated to the 2nd or 3rd century AD, although some finds do not correspond to the precise dating, adding to an already fuzzy understanding of Nubian chronology.

Temple of Apedemak

Located to the west of the temple of Amun is the temple of Apedemak (or the Lion Temple). Apedemak was a lion-headed warrior god worshipped in Nubia. The god was used as a sacred guardian of the deceased hereditary chief, prince or king. Anyone who touched the chief's grave was said to be cursed by this Apedemak.

The temple is considered a classic example of Kushite architecture. The front of the temple is an extensive gateway, and depicts Natakamani and Amanitore on the left and right exerting divine power over their prisoners, symbolically with lions at their feet. Who the prisoners are exactly is unclear, although historical records have revealed that the Kushites frequently clashed with invading desert clans. Towards the edges are fine representations of Apedemak who is represented by a snake emerging from a lotus flower. On the sides of the temple are depictions of the gods Amun, Horus and Apedemak keeping company in the presence of the king.[3] On the rear wall of the temple is the largest depiction of the lion god, and is illustrated receiving offering from the king and queen. He is depicted as a three-headed god with four arms.[7] The north-front shows the goddesses Isis, Mut, Hathor, Amesemi and Satet. Inside the temple is a carving of the god Serapis who is depicted with Greco-Roman style beard. Another god with a crown is depicted but is unidentified, but believed to be of Persian origin.[3]

Although the architecture of the main Apedemak temple is strongly influenced by Ancient Egyptian architecture, exhibiting some classic Egyptian forms, some of the depictions of the king and queen are fine examples of the differences between Egyptian and Kushite art. King Natakamani and Queen Amanitore are depicted with round heads and broad shoulders, with the relief of Amanitore having unusually wide hips, which is more typical of African art. So the temple of Apedemak illustrates profoundly the fusing together of artistic influences by the Kushites, especially when taking into account the nearby Roman kiosk which clearly is influenced by Ancient Greece and Rome (as discussed below). The depiction of Apedemak displaying a lotus flower is also somewhat unusual, and initially led early archaeologists of Naqa to speculate that the temple had Indian influences, given that trade routes from India led to the ancient Red Sea port of Adulis, in modern-day Eritrea.[3] These connections are still being explored by modern archaeologists.[8]

Pylons depicting King Natakamani and Queen Amanitore smiting enemies. The queen holds a sword, the king an axe

Pylons depicting King Natakamani and Queen Amanitore smiting enemies. The queen holds a sword, the king an axe Three-headed Apedemak with four arms

Three-headed Apedemak with four arms Apedemak as a coiled snake with lion’s head

Apedemak as a coiled snake with lion’s head

Roman kiosk

The Roman kiosk is a small temple near the main temple building, which has strong Hellenistic elements. The entrance to the kiosk is Egyptian and is topped by a lintel with a row of sacred uraeus (cobras) but the sides consists of columns with florid Corinthian capitals arched windows in the Roman style.[3] Recent excavations at the building showed that it was probably devoted to the worship of Hathor. Testament to this is the discovery of a statue of Isis, a goddess in Ancient Egyptian religious beliefs, whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis is the Goddess of motherhood and fertility who was worshiped as the ideal mother, wife, matron of nature and magic.[9] The goddess Isis was known to have absorbed some characteristics of Hathor.[10]

Other

Standing at the foot of the sandstone cliffs of Jabal Naqa is the temple named "500". It was built by Shanakdakhete around 135 BC, making it the oldest building on the site. The texts on the temple walls are the oldest known writings in Meroitic hieroglyphs. Judging by the reliefs, the temple was dedicated to the Theban triad of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu, as well as Apedemak. In 1834, Giuseppe Ferlini discovered treasure which was severely damaged. A thorough excavation and restoration has been made since.

See also

References

- "Naga Project (Central Sudan)". Poznań Archaeological Museum. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- UNESCO Island of Meroe.

- Clammer, P. (2005). Sudan. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 128–131. ISBN 978-1-84162-114-2.

- "History of the archaeological sites of Sudan". Wata. Retrieved 2020-03-04.

- Vincent Arieh Tobin, Donald B. Redford (ed.), Oxford Guide: The Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology, Berkley Books, p. 20, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- ZDF-"Heute-Journal", January 12, 2006

- Claude Traunecker (2001), The Gods of Egypt, Cornell University Press, p. 106, ISBN 0-8014-3834-9

- Randi Haaland (December 2014), African Archaeological Review, 31, pp. 649–673, ISSN 0263-0338

- R. E. Witt (1997), Isis in the Ancient World, p. 7, ISBN 0-8018-5642-6

- Veronica Ions (1968), Paul Hamlyn (ed.), Egyptian Mythology, ISBN 0-600-02365-6

Literature

- Dietrich Wildung; Karla Kroeper (2006), Naga - Royal City of Ancient Sudan (in German), Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, ISBN 3-88609-558-4

- Basil Davidson Old Africa Rediscovered, Gollancz, 1959

- Peter Shinnie Meroe, 1967

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Naqa. |